by Geoffrey Clarfield (October 2022)

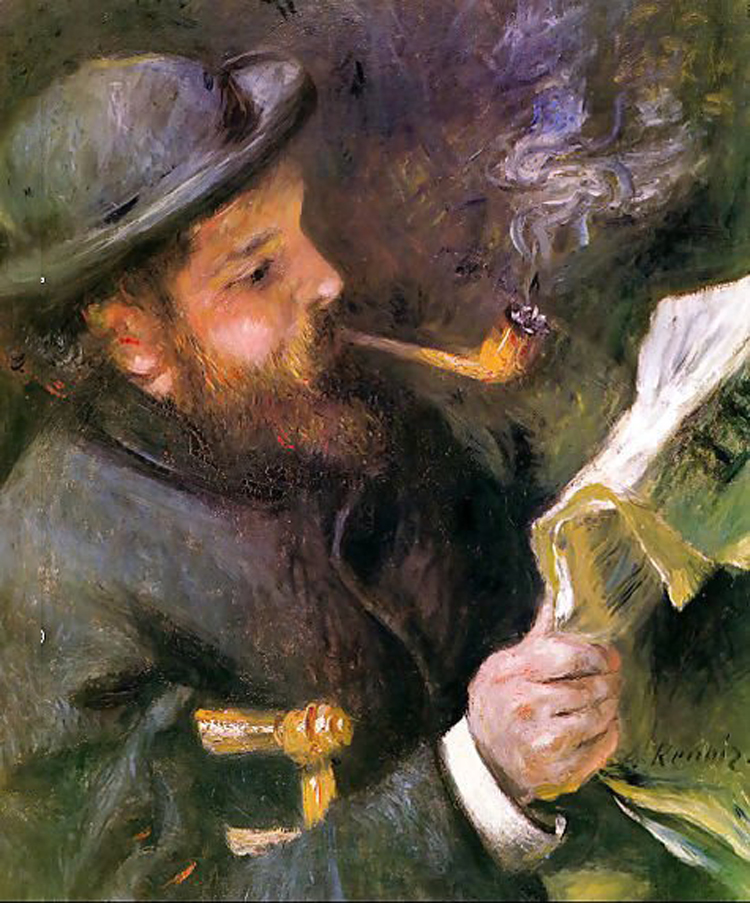

Claude Monet Reading A Newspaper, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1872

Hassan was bringing me my morning tea. The sun was rising above the courtyard of my house in Tangier’s old city, Medina in Arabic. I could hear the traffic getting louder and the older street hawkers crying out “Bambelamousse,” an Arabo Berber version of the French “Pamplemousse” or grapefruit which they sold by the slice, two dirhams a piece.

I was reading the newspaper, still printed and not yet digital, Le Monde Marocaine whose latest editorial was based on an interview with the new King, who was explaining why Morocco might just decide to recognize Berber independence, or autonomy, in the Kabyle mountains in nearby Algeria. I understood that was because the Algerians did not recognize Moroccan sovereignty in the Spanish Sahara. Plus ca change as they say in Paris.

I had been meeting with legal and illegal antiquities dealers. My job as Israel Cultural Attache to the Kingdom of Morocco made me sensitive to much of the Judaica that still could be found on the black market here. Old Hebrew Bibles that had been written in the Sahara, Kabbalistic texts brought from Spain in 1492 after the expulsion of the Jews and of course, ancient jewelry from Andalucía.

Hassan had invited one of these borderline merchants to the house for lunch. His name was Sharif, yes as in Omar Sharif of the film Lawrence of Arabia. Sharif had a round head, a short mustache and trimmed beard, eyebrows that went from one side of his head to the other, well articulated ears and a mischievous smile, like a first-year undergraduate at an American college.

French anthropologists during the colonial days had romanticized and politicized the contrast between low land (corrupt) Arabs and highland (uncorrupted) mountain dwelling Berbers. There was and is something to this, as the Berbers I had been meeting did have a confidence and forthrightness that was missing among the peoples of the cities and the plains.

The Moroccans themselves have a word for this. My colloquial Arabic teacher explained it to me. The Arabs have mostly lived in the land of the “Machzan” the lowland territory of the Sultan, while the Berbers have lived in the land of dissidence, of freedom called the “Sibah” under their tribal chieftains, a bit like the lowland Arabs and highland Kurds of Iraq, or lowland and highland Scots before their defeat by the lowland Scots and English at Culloden battle in the mid 1700s.

Sharif, like all good antiquities dealers, had more than a few stories to tell. His favorite was about a Viennese woman, two decades older than him who bought antiques from him, by giving him sexual favours and money. Who was paying what to whom for what, always confused me and would have driven any feminist scholar crazy. Luckily, gender studies never attracted me when I studied anthropology of the middle east.

I had ordered two croissants from the local French bakery and as we dipped our bread in the already sweet tea Sharif told me a fascinating tale.

“You see, it is a long story,” he said. “My grandfather tells me that some generations back, way up in the Atlas, they met an English Gentlemen. He called himself Theodore. He was an Italian, who claimed to be a Greek of some sort. You know, a Byzantine, “Roumi” as we call them in Arabic. He lived like a great Lord in England but as he was a foreigner, he was called upon to kill the opponents of the King or Queen of England during his lifetime. He was what you would call a 17th century James Bond, an assassin really.

I had read bout this man but as Sharif did not speak or read English I wanted to know if his family had received and kept up an oral tradition about him.

“I know the following,” he continued. “Or as I should say this is what has been passed down in my family … he did not look like an Englishman. He looked like a man from Fez; Arab, but with blue eyes. He carried himself as if born to rule. Why? I do not know. They say he was born in the mid 1500s and came here many times in the early 1600s when the ancestors of our present king established their Alawite ascendancy.

“He was, as they say, an assassin and worked for British Lords. We believe he worked for the Sharif of Lincoln and another Sharif called Clinton, like the American President. Our family knows of him because my ancestors allowed him to keep a hidden monastery of Greek Christians up in the highlands of the Atlas in the territory of what later became that of the Glaoui Pasha, who ruled much of the Atlas under the French. El Glaoui was also—how do you say— “a pimp”? He ran 12,000 prostitutes in a special quarter of Marrakech which added to his Croesus like wealth.

“Anyways, these monks spent most of their time praying but they were exceptionally good with money and provided local traders with credit, and my own family with the capital to start their export trade to Liverpool where some Moroccan Jews and had already set up shop. This is the Edri family. They were also learned Rabbis and scholars.”

Sharif continued. “He also sold old books. They were printed or handwritten on calf skin, with pictures. We, as good Muslims, thought they were dirty— ‘haram’ —as we do not believe in pictures in books. But we did help him smuggle them to England and he gave us ten percent on each transaction. My ancestors became rich on this trade, they bought land, hired retainers and by the early 20th century we were considered among the prominent ‘Lords of the Atlas.’”

I had read a recent biography of the man. Here is what Wikipedia tells us about this notorious Byzantine blade for hire:

Theodore Paleologus (Italian: Teodoro Paleologo; c. 1560 – 21 January 1636) was a 16th and 17th-century Italian nobleman, soldier and assassin. According to the genealogy presented on Theodore’s tombstone, he was a direct male-line descendant of the Palaiologos dynasty, which had ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1259 to its fall in 1453. Though most of the figures in the genealogy can be verified to have been real historical figures, the veracity of his imperial descent is uncertain.

Born in Pesaro around 1560, Theodore was forced into exile after being convicted for the attempted murder of man called Leone Ramusciatti. He lived in exile for many years and went on to become a proficient soldier and hired assassin. In 1597, Theodore arrived in London, hired by the authorities of the Republic of Lucca to kill a man named Alessandro Antelminelli. After failing to track down Antelminelli, Theodore stayed in England, possibly for the rest of his life.

In 1600, Theodore was hired by Henry Clinton, the Earl of Lincoln, ostensibly as “Master of the Horse” but in reality probably as a henchman and assassin. At the time, Clinton was perhaps the most hated nobleman in the entire country. Theodore probably accompanied Clinton on his visits around the country, most of them having to do with Clinton’s frequent battles with the law. In Clinton’s service, Theodore also met the famous captain and explorer John Smith, whom he gradually helped introduce back into society after Smith had elected to live as a recluse.

While living in Plymouth in 1628, Theodore was offered employment by the Duke of Buckingham, George Villiers, almost as hated as the now deceased Earl of Lincoln, but Villiers was assassinated soon thereafter. Theodore was then invited by a Sir Nicholas Lower to stay with him at his house, Clifton Hall, in Landulph, Cornwall. There, Theodore lived until his death in 1636. He was buried at Landulph and was survived by five of the six or seven children whom he had with his wife, Mary Balls. Of these children, only Ferdinand Paleologus, who later emigrated to Barbados, is known to have had children of his own.

The sun was shining in my courtyard. The clouds were passing the sun. We were alternately bathed in shade and sunlight. Sharif took out his long sebsi or pipe, filled it with the what the Moroccans call kif (local marijuana) and began to smoke. We were quiet. Down the lane we could hear a radio broadcasting the languid tones of Um Kulsum, the great Egyptian diva of the early 20th century belting out her classic song ‘Inta omri|’- You are my life.

Sharif smiled at me and said, “I have kept one of these manuscripts. It is for sale. Would you like to see it?” I was stunned. I felt like I was a character in an Umberto Eco novel. I asked myself, “Did he have a Greek Byzantine translation of some unknown or lost ancient Greek or Latin classic?” Sharif told me it would take five days to walk to his family home, off the beaten track in the High Atlas and we were to set off the next day.

We left at sunrise and six hours later we came to the end of the road. We were met by two Berber guides and four mules with saddle blankets. The men wore white turbans and colorful woolen cloaks and the typical Moroccan yellow sandals. They carried staves and guided us up the mountain paths.

We crossed peaks with remnants of winter snow upon their slopes, mud castles or kasbahs one hundred feet high and rode by tattooed Berber women who were cutting their wheat with handheld sickles, similar to those first invented in ancient Sumeria. An outbreak of rocks displayed engraved rock art from the Neolithic.

On one occasion a village elder presented us with a bowl of fresh goat milk which we all consumed with gusto. Another village head invited us to tea. His wife served. I asked if she was a good woman. He said, ‘Exceptionally good.’ A second woman came to help, and he told me she was his second wife. Mezyan bezzaf, he said in Arabic. ‘Incredibly good’ motioning towards her, with a wide, impish smile.

We finally reached Sharif’s family dwelling. I felt a bit lightheaded, breathing in the cool, unpolluted mountain air. We feasted on a meswhi made of lamb flavoured with apples and a couscous with olive oil that came from his farm, all consumed with round Berber bread fresh from an oven, whose form had changed little since the Neolithic. Maybe his ancestors had carved those rock engravings. Who knows.

The next morning it was my turn to sip tea as Sharif’s guest. We talked politics, economics, music and literature. He was a fan of Leonard Cohen, in the French of course, and liked his music very much. He had been married in France to a Catholic woman. He had put aside Islam and assimilated into French culture but one day he woke up, felt like a fraud, got a divorce and came back to his ancestral mountain home.

He told me, “Wanting to be Western and being Western are two different things. Like Islam. To be Western you need to be born into it. That is why the Americans will fail in the middle east. They say their culture is voluntary, but you need to breathe the American air of freedom from childhood, otherwise you do not adjust. It cannot be exported. France is similar.”

Without a pause Sharif got up and brought me a book. It was a Byzantine manuscript. I could read the Greek. I opened the first page. This is what it told me.

“My name is Plutarch. I am nothing to speak of for I am a conquered man in my own city. I offer this book to all who want to gain wisdom. It is the story of Epaminondas who fought to free the oppressed slaves of the Spartans. Their ancestors had once been free men, centuries earlier. He did not fight for wealth and fame. He fought because he believed that all men are born free. He was a follower of the searcher after wisdom, Pythagoras and he has much to teach us…” I was stunned. This book had been missing for just under two thousand years.

When we went back to Tangier, I got out an article from some papers I had brought with me, and that I had photocopied at the Princeton University library where decades earlier I had been a student of Bernard Lewis. I remembered my student days when I studied as an undergraduate and when my friends made fun of my desire to learn ancient Greek. They warned me that one day I would be erudite and poor. All too true. The article is by a scholar called Frakes.

When we went back to Tangier, I got out an article from some papers I had brought with me, and that I had photocopied at the Princeton University library where decades earlier I had been a student of Bernard Lewis. I remembered my student days when I studied as an undergraduate and when my friends made fun of my desire to learn ancient Greek. They warned me that one day I would be erudite and poor. All too true. The article is by a scholar called Frakes.

Paul Louis-Courier had somehow missed this one. How it had gone from Byzantium to North Africa, Italy and back to the Atlas I do not know, except for the fact that Sharif’s family had hidden Greek monks for centuries and, descendants of Emperors as a rule, have very extensive networks. I will never really know the answer.

What I did know is that this book could be my passport to an early retirement. I had obtained it during my one month of official leave where I was told in no uncertain terms by my boss,

“When you are on leave here in the Kingdom of Morocco you are not on a diplomatic passport. You are your own, man. If you are in trouble, we cannot help you. Any transaction that you carry out of any kind is your own responsibility. “Well then, that was pretty clear.

Sharif was eager to cut a deal. He had had the book approved by the antiquities authority for sale. No one spoke Greek in that office, and it had pictures that offended Muslim propriety. I promised to pay him 5000 US dollars when we returned to Tangier. (When I got home, he placed the manuscript in a brown paper bag and handed it to me with a flourish. He counted out the $5000 and pocketed the cash. I still have the receipt.)

We retraced our steps down the mountain. We met a car at the main highway that took us to Tangier. I returned home, tired. I took a hot shower. I took out my sebsi, a gift from Sharif. I lit up, started dreaming about Byzantine scribes and fell asleep.

The next morning, I woke up and saw the paper bag lying beside my bed. I opened it and carefully held the manuscript up to the light as if it were a newly born baby. I read the whole thing in a day. I did not need my sebsi. I was high on Plutarch and Epaminondas. Soon after I planned to sell the manuscript to the British Museum. I expected a half a million pounds if it were to be auctioned at Sotheby’s and I would then buy a house in Tangier, in the Kasbah.

I had recently heard about the existence of an original, illustrated copy of the Zohar, the central book of Kabbalists that had been brought to Morocco by fleeing Jews from Spain in 1492. They had been cruelly and unjustly expelled by Ferdinand and Isabella the patrons of Christopher Columbus the explorer, who noted their expulsion in his diary as it was the day he sailed from Spain. It was my birthday that day and I was feeling extremely confident.

I had arranged to host a dinner with Sharif and a few guests, Claude from the Alliance Francaise, Hector from Cervantes institute and Helmut from the Goethe Library. I also invited Josh from the American Legation Museum. I really wanted to make an impression on my colleagues.

As they arrived Sharif called. As Moroccan time is not Western time, I thought this was very thoughtful of him for in this country you can arrive a half hour or more than an hour late for an engagement and no one bats an eyelid.

He said he had just had an unexpected visitor from Vienna, that he was temporarily delayed, and would arrive at my place soon. I told him not to worry and said to him in Arabic, “Allah yi kathir kheirak” May God give you happiness.

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

You write interesting tales. I always wonder how factual they might be, or are non-fiction?

Hello:

It is a mix of fact and fiction. Of course the manuscript is not real, but perhaps one day it or something like it will be discovered. Much of the local detail is based on my living in Morocco in the late 1970s and included a walking trip in the high Atlas.