Modern versus Biblical Liberty

by Friedrich Hansen (October 2023)

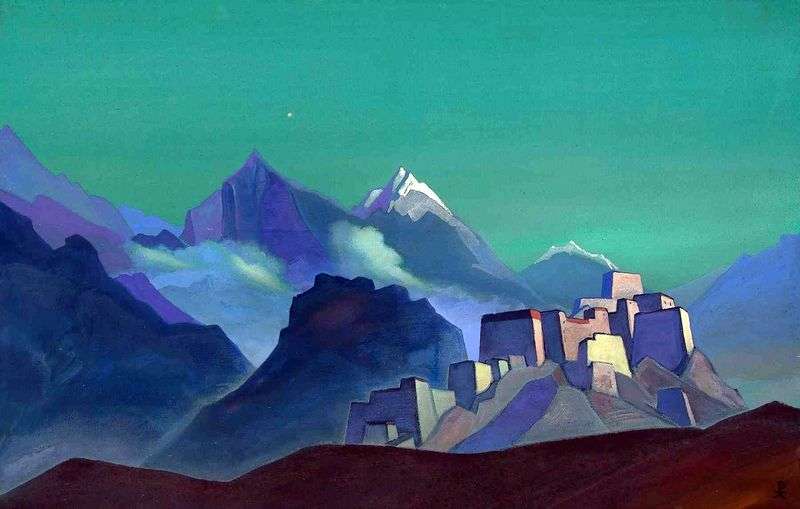

Star of the Morning, Nicholas Roerich, 1932

The biblical image ban, granting the incorporeality of the divine, is crucial to Judaism. For God cannot be eternal and embodied at the same time because obviously the latter would make him perishable. Christianity answers to this dilemma with the old Asian concept of visible resurrection (rebirth) which brings with it the notion of proxy-ism unacceptable to Judaism’s concept of the human person. Out of proxy-ism certainly arises the notorious antisemitism as well as the Western obsession with authenticity and its spurious remedy: the proxy of sexual identity. By contrast, Judaism favours the multitude or community as much as the individual. This has been put in the timeless phrase “Lord of hosts” encompassing the living, the not yet born and those who have passed away. For the divining, meaning the proscribed as much as foreseeing community, is virtual and based on the revealed word quintessential to the auditive paradigm of Judaism. It does not suffer any descent into visible corporeality that renders “oneness” perishable. By contrast, the auditive paradigm is based on the religious image ban and betrays the oriental disposition shared by semitic linguistics and the ban on all too corporeal vowels. Which brings Judaism much closer to Islam than to Christianity and abhors anthropomorphic visual metaphysics. This same anthropomorphic handicap renders feminism pointless by and in itself but grants the equality of all human beings before God regardless of bodily features.

Guy G. Stroumsa, formerly religious scholar at Hebrew University, observed that identity politics and autarky in self definition emerged in late antiquity witnessing the decay of the Greek polis. The stoics, back then a variety of Gnostics, distanced themselves from revelatory deeds on principle. Likewise, todays postmodern woke globalists are diminishing deeds while considering themselves the last men to witness the worlds inevitable fall. I would like to claim that in both cases the denial of deeds is behind the loss of reassuring community and has inverted the axis of personal orientation from centripetal (tied to the Greek polis or religion) toward centrifugal groupism just as in todays identitarian rainbow embraced and bankrolled by the West. (See also Egyptologist Jan Assmann: “Inventing the inner person,” p. 51).

However, Stroumsa speaks about the exact opposite process, calling internalization what I described above as inner visualization and transgression of the religious image ban. In the manner of the mirror effects of the visual paradigm he speaks of “cosmicisation” as a form of “internalization” in the sense that globalization frees people to opening up to the world and dropping all restraint while at the same time makes them feel lost. This eventually prompts them to embrace the identity nearest to them: self-identifying with their sex.

With the full view of the cosmos in front of them the Stoics performed the “cognitive turn” and identified with the stars, a sort of re-birth through astrology. It was Hans Jonas who in his monographs on the modern Gnosis depicts it as a replay of the same thing in late antiquity. He observed many similarities in terms of degradations between the 1930s and in late antiquity. What strikes him as similar is the disengagement from civic religion and official cults today as in late Hellenistic times. This created all sorts of self-identified personal religions, labeled inward religion by Stroumsa. Some of those are fake or pagan inwardness since they confuse the religious-auditive with the haptic-visual rather by that replacing the ethical orientation toward the other with solipsist corporeal self-identification. The result are frank idolatries such as today’s environmental warriors trying to make good for the sexual depravities of identity politics.

Apparently, I am much more in agreement with Jonas than with Stroumsa in particular as the former rightly notes that the Gnostic movements prepared the way for the anthropomorphic idolatry of Christianity which is behind its present decline. Stroumsa quotes E. R. Dodds describing the times in the centuries preceding Christ as marked by a “fear of freedom” which was symptomatic for Gnostics in the Hellenistic age.

In early Judaism we also see changes brought about by the reception of Hellenistic science and philosophy as well as “sapientism” which accounts for a more subjective and at the same time erudite Gnosticism. In Christianity, all depended on sincerity and faith as the facilitators of subjective feeling and “inwardness,” necessary for forming the new religious identity. As such, it promoted piety and the rejection of pagan cults. Yet Stroumsa notes that there are only two characteristics or premises of the new Christian faith: first the split view of a universalist reality: “Weltanschauung” and second a choice between dogma and error to be made by the individual. This is the source of Christian social identity as well as of Christian intolerance liable to controversy early on. Both features are inseparable from each other, as is the impulse for fighting and aggressive canvassing of others. Identity politics follows this pattern in our own times. In its secular orientation it attached itself to sexual performance and is also repeating the proselytizing with growing degrees of intolerance. This corresponds pretty much to the plunge into the visual paradigm that is typical for religious decay towards organic ethicism. Which is exactly what Stroumsa detects upon the emergence of the individual in late antiquity concurrent with the advent of Christianity. It is a very complex process meant to bridge the Platonic dualism of body and soul.

Unsurprisingly there is some similarity in this to the present political divide in the West between the corporeal woke left and the spiritual populist right. It is useful in this context to remind everyone that, several millennia earlier, Judaism ascended from eye to ear through the biblical covenant. It meant rising from the Pharaonic to the heavenly yoke and was probably the first ascension toward self-determination in human history. It occasioned the foundational internalization and sublimation of the bondage of the body during slavery. Somehow the opposite route was undertaken by Christianity by descending from the auditive heavenly yoke of God in Judaism to the earthly authority of the church depending on the incarnation of his son.

Christ represents an externalization of personal sacrifice though symbolic proxy suffering, meant to serve as role model to be visually imitated. Judaism, by contrast, maintains the image ban in order to walk under the unadulterated auditive guidance of the divine being. The intellectual parallel of Christian descent is being claimed by the postmodern reappearance of Gnosticism. As in late antiquity todays woke populists attend to images, suppressing the spoken word by PC censure, narrowly contending themselves with virtue signalling. Only the revived Orthodoxies are committed to the truth by sticking to the revealed promise which is nothing less than spoken word bound to the confirmatory deed.

It was Shlomo Pines who observed that in late antiquity the Hebrew term Herut (for freedom and national liberation) took on the Greek meaning of eleutheria or libertas in the polis. While Jewish freedom implies a spiritual inner choice against instincts on behalf of (more often than not) altruistic divine commandments, Greek liberty does refer primarily to instinct expression. It was with Pauline Christianity that this freedom lost its affirmative link to Jewish national liberation, i.e., freedom from foreign rule in Egypt. Subsequently it came to mean the opposite: liberation from self-rule tied to the divine law. Pines called this the most consequential event in early Western history. But contrary to Stroumsa, who has framed this as spiritualization, it is anything but. Rather we are talking about a visual internalisation or somatization through Christ. Thus, Jewish spiritual obeisance or auditive “imitatio dei” was being turned into Christian visual mimicry. For Paul famously dispenses of the Jewish law and leaves the individual human creature completely unhinged, rendering the flesh speechless. For Augustine, under the influence of Plato, this would mature to the search of knowledge of God being replaced by self-knowledge which accounts for nothing less than the emergence of Gnostic identity politics of old.

The Neoplatonism of Plotin, the founder of Gnosticism, had already discovered that God is present inside of each person. In Judaism however God remains firmly outside of ourselves and tied to the commuity by virtue of real deeds (to our neighbour) which are essential for underwriting our words. This is the meaning of “walking in Gods ways” which cannot happen inside of us alone as in Protestantism. The only difference between Plotin and Augustine is this: the former is more static and the latter dynamic. While Plotin is “identitarian” and keen at discovering his “inner self,” he is prone to encounter his instincts instead. Augustin is more honest by putting up a fight against his own instincts. However if this turns into enmity, Christians may “get out of touch” (Stroumsa) with their body permanently “because it can be frightening and the fight daunting.”

Static and Gnostic Platon had no idea of such inner dynamics as the öate medieval “Pilgrim’s progress,” by which the Christian really descends into his flesh with the aim to domesticate his inner hell. This however has also given rise to the treacherous (Augustinian?) and dialectic concept of the “holy sinner.” The deeper you dig into sin the stronger your holiness after you emerge victorious from the fight. The heroic moral imagination of Gregory of Nyssa would even aim at going back in time until paradise and undo Eve’s and Adam’s sin. Actually, this has frequently been a vision of Christian mysticism with its ascetic punishment of the body. Yet ill-conceived self-punishment and flagellation is utterly alien to Orthodox Judaism. Rather, in the name of self-purification, we are called for the inward sacrifice which enables the ethical yet outward deeds and ritual of Judaism.

By contrast Paul’s rejection of Torah in the name of false liberation would remove all Jewish protections against the abuse of the human body as well as the human spirit. The latter was further abused by the Gnostic, “purified reason” of Hegel and the thinkers of German romantic idealism. All these pathologies of the spirit and the body are likely to be unintended consequences of Pauline internalization of monotheism. They may well be behind many psycho-pathologies of modernity either such as anorexia and other compulsive disorders and addictions. It is in the context that A D Nock called Gnosticism the “Platonism run wild.” Hostility and rejection of the body, the Greek pneumaticoi or matter in general is the most common feature of self-righteous internalizations of the Gnostic persuasion. Gnosticism is not interested in the human person at all, nor does it support subjectivity, human conscience, ethical judgement or moral agency.

Heresies in the manner of esoteric mysticism have much to do with disclosure of secret knowledge and the fear of martyrdom, in Shia Islam also known as taqiyya which, according to Stroumsa, is directly linked to consciousness of “interiorisation” and the conviction of privileged possession of interior truths. This is likewise true of several Protestant denominations. If it’s based mainly on the visual paradigm and images, it can be likened to the “hardening of the heart” with Pharaoh in confrontation with Moses, meaning a closing of the mind as defensive capacity.

Finally we need to understand the natural ambiguity of Gnostic heresies with their distinction between inner and outer self. This has been historically visualized into the Christian dualism between Jesus and the Oikomene (interiorisation versus cosmicisation). It puts the individual at risk of creating an antagonistic polarization of the “ontological difference” between the visual and auditive paradigm. One obvious escape route from this calamitous inner antagonizing mentality would be to attach oneself recklessly to the haptic (sexual) paradigm. This is what gave us sexual identity politics under the auspices of Egyptomania in the fin de siecle in late 19th century. Rarely has been humanity so hopeless as in the pagan worship of the unforgiving sun deity and its nether-worldly agent, the minuscle scarab of Pharaonic times. But nevertheless, it was under those auspicies that identity politics was born and became the philosophical inspiration of Sigmund Freud.

Table of Contents

Dr. Friedrich Hansen is a physician and writer. He has researched Islamic Enlightenment in Jerusalem and has networked on behalf of the Maimonides Prize. Previous journalistic and academic historical work in Germany, Britain and Australia. He is currently working in Germany and Australia.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast