Music Inspired by Remarks, Nature, and God

by Kenneth Francis (November 2022)

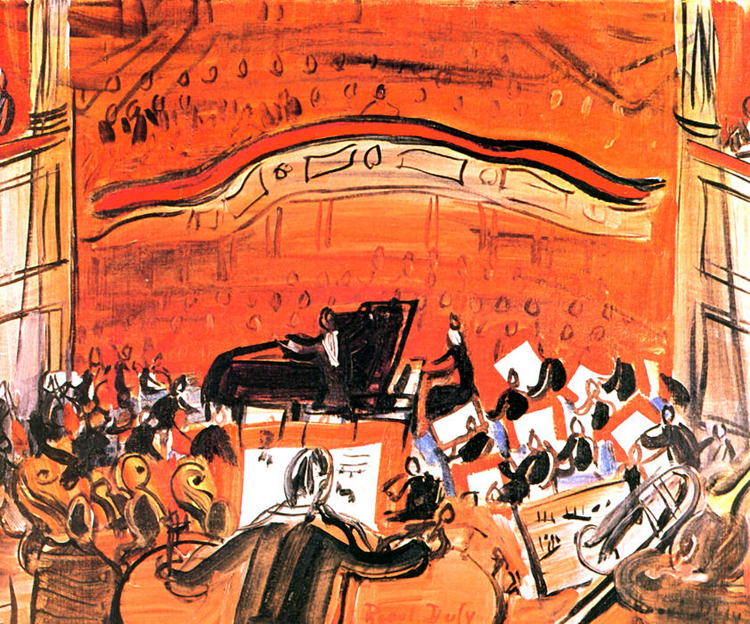

Le Rouge Concert, Raoul Dufy, 1946

Have you ever wondered what inspired some of the world’s most popular lyrics and melodies? Consider Garth Brooks’ country and western monster hit “Friends in Low Places,” arguably the most popular singalong ditty over the past 30 years. I don’t particularly like the song, but I’m intrigued by the origin of its lyrics.

According to Earl Bud Lee, one of the song’s co-writers, the idea of the hit came about when he and some friends had eaten lunch in an eatery in Nashville. After the meal, Lee discovered that he had forgotten his money, hence he couldn’t pay the cheque. When asked how he was going to pay the bill, he allegedly said, “Don’t worry. I have friends in low places: I know the cook.”

When Lee’s song-writing buddy, Dewayne Blackwell, heard this, he felt as if the line had potential for a song. Some months later at a party, the pair, writing on paper napkins, began writing what was to become a massive hit. They later approached Brooks, a then struggling musician, and the rest is Country & Western history.

Another throwaway remark that inspired a classic of a more sophisticated song, is the 1967 hit, “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” sung by British group, Procol Harum. I regard this as one of the greatest songs of all time but I haven’t got a clue what it’s about (I hope it’s not blasphemous!). However, its origin is less poetic and more psychedelic.

The inspiration for the song’s idea is explained by the band’s lyricist, Keith Reid. He said he got the title and starting structure of the song at a party, when he overheard someone saying to a woman: “You’ve turned a whiter shade of pale.” Reid and band members Gary Brooker and Matthew Fisher completed writing/composing the song, with its Bach-derived instrumental melody. The result, when released, was it reached Number One in the UK charts for eight weeks and selling over 10 million copies worldwide.

The Beatle John Lennon said it was his favourite song, and would play it regularly on his jukebox. Lennon was also inspired to write a hit song by some throwaway comment made by his bandmate, Ringo Starr. That song, and film title, is “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Lennon said: “The title was Ringo’s … He [once] said after a concert, ‘Phew, it’s been a hard day’s night.’” Lennon also said of another Beatles’ song, “Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite,” that he got the inspiration from a 19th-century circus poster that he bought while shooting promotional films. “Everything from the song is from that poster,” he said. Paul McCartney, who is credited for co-writing the track, said that “the song just wrote itself.”

Other Beatles’ songs oddly inspired were “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” In the case of “Lucy,” Lennon said that his inspiration for the song came when his three-year-old son Julian showed him a nursery school drawing that he called “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” As for “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” Paul McCartney got the title from hearing a catch-phrase that was often expressed by Nigerian conga player, Jimmy Scott Emuakpor, when he addressed his fans with the above words, to which they’d reply: “Life goes on!”

In another throwaway remark, the great soul singer Dionne Warwick had her first solo recording of the song “Don’t Make Me Over” in 1962. However, during a tiff about wanting to sing another song, Warwick yelled at composer Burt Bacharach, “Don’t make me over, man!” and stormed out of his office. Bacharach and lyricist Hal David quickly composed a song inspired by what she said and offered it to her. It was also covered in 1966 by the British Merseybeat band, The Swinging Blue Jeans.

Another love song was composed by James Thornton, when he wrote “When You Were Sweet Sixteen,” in 1898. He was inspired by his own words when his wife, Bonnie, asked him if he still loved her. Thornton replied, “I love you like I did when you were sweet sixteen,” hence, the song was over the past 100 years covered by the world’s greatest singers and sold millions of copies.

From pop music to philosophy: Arthur Schopenhauer and Fredrich Nietzsche were key influences on the German composer, Wagner. Regarding Schopenhauer, Wagner derived the ideas of subjection and redemption that are apparent in “Tristan und Isolde,” “The Ring,” and “Parsifal.”

Even the solar system inspires popular music, with such orchestral suites as “The Planets,” by Gustav Holst, despite ignoring some astrological factors. From the cosmos and philosophy to theology: When it comes to artistic inspiration, it’s hard to beat the Bible. The 1960s’ Number One hit song “Turn! Turn! Turn!” was written (arranged) in the late-1950s by the late Pete Seeger. The lyrics, except for the title, are taken almost verbatim from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

Another example of Bible verse set to popular music is Boney M’s “Rivers of Babylon” (Psalm 137:1), which stayed at Number One in the UK charts for five weeks in 1978. In fact, the Psalms are infused with references to singing the praises of Our Lord.

But it’s not just the words from God or humans that inspire such great music. We also see this mimesis when music imitates nature. It can reasonably be assumed that Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestral interlude “Flight of the Bumblebee” was inspired by the chaotic sound caused by honey-making creatures as they ascend from the hive.

Even creatures from the ocean can inspire. Many years ago, the late Irish Taoiseach (PM), Charles Haughey, said he believed the original source of music that inspired an ancient Irish folk song was the sound of a humpbacked whale. He tells the story of three men at sea, sitting in their *currach, motionless, and that the hull of the boat would act as a reverberating sounding board for the ‘music’ of a whale, which passes by the Blasket Islands, off County Kerry’s Dingle west-coast. (*This is a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were stretched.)

Haughey, who bought Inishvickillane, the most southerly of the Blasket Islands, theorized: “A yachtsman friend from Cork, Eugene O’Malley, was anchored one night at the inish [one of the islands], and he suddenly heard this [whale] ‘music’ and was intrigued by it … He later made a recording of it [“Port na bPúcaí” (Port of Pucks)] and sent it to National Geographic, which in turn sent it back to him with a tape recording of the humpbacked whale. O’Malley then put the two recordings side by side and they sounded almost identical.”

Also at sea, the mimeses of another tune that was probably inspired by fowl of the sky, is “The Lonesome Boatman,” composed by Irish folk-music duo, Finbar and Eddie Fury. It features the haunting sound of a tin-whistle sounding like the squawk of a seagull echoing high above a boatman, as he casts his nets. Similarly, but less squawky, is Fleetwood Mac’s 1968 Number One classic, “Albatross.”

The composition and arrangement of this beautiful masterpiece conjure up a calm sea setting beside a remote beach, with cymbals imitating the sound of waves gently flowing across the sand, accompanied by the dreamlike solo from Peter Green’s incredible guitar riff. The song, which was written by Green (the founder of Fleetwood Mac), was inspired by the 1798 poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by English poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

From being inspired by throwaway remarks to mimeses in nature, to the words of Plato: “Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, gaiety, and life to everything. It is the essence of order, and leads to all that is good and just and beautiful.”

While I partially agree with Plato’s sentiments, the ancient Greeks never quite got their theology in order to merge with the Logos (God). Plato was probably attributing such music with Apollo, the daughters of Zeus, or the concept of Platonic forms. For it is not music that is the moral law, essence of order, and all things beautiful. It is God: The Logos incarnate.

In the coming weeks, as you stroll through the shopping malls of suburbia and the metropolis main streets, you’ll no doubt hear the secular, saccharine, elevator musak of “White Christmas” or “Winter Wonderland” —compared to the Divine music of “O Holy Night,” sung by charity fundraising carol singers outside the malls’ doors and on the sidewalks. I know which bucket I’ll be inspired to chuck my spare change into.

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast