My Friend Ron: Baseball Memories

by Samuel Hux (December 2017)

I have a radical theory in support of a conservative view of a game. Aware that this journal is out of both Nashville, Tennessee and London, England, I alert the Brits and others of the Empire and the erstwhile colonies that the game I speak of is not that incomprehensible phenomenon called cricket, but rather The Game, baseball that is. If some of the terminology, rules, and names I discuss are unfamiliar to you non-American culturally deprived, then join the likes of me as when a dear Jamaican pal talks about that thing you do with a wicket.

Most baseball purists claim that the Designated Hitter rule instituted by the American League in 1973 is an abomination because one of the nine, the pitcher, does not bat, thus radically altering the game as it was designed by its wise founders and allowed to evolve. This is nonsense. When the professional game began in 1876, the standard batting average was around .260 (including the pitchers’). That .260 or so has remained consistent ever since, no matter the occasional explosive season—for position players that is! Pitchers’ batting averages, however, began to fall, noticeably and then drastically: .224 by 1893, .177 by 1913, and by 1972, the year before the DH rule, .148. Why? My theory which I call “precedential expectation” holds that players learn to do what they are expected to do (given athletic talent and within physical possibility), and that progressively pitchers were allowed to become defensive specialists and not expected to be good hitters and eventually therefore became lousy hitters. (This radical notion is explained at probably exhaustive depth in another essay, and very convincingly I modestly assert.)

So The Game, which the founders and early developers imagined to be a matter of nine players contributing both offensively and defensively, slowly degenerated into one in which eight players contributed both ways while one, the pitcher, contributed defensively and was more or less forgiven for being an offensive vacationer. That is, the starting lineup meant eight and one half players instead of nine. When the American League sat the pitcher down on offense and replaced him in the batting order with the DH, then-American League teams had a full complement of nine on defense and nine on offense. A return, in other words, to the nine versus nine the founders intended. Baseball as God and Nature planned. The DH rule therefore was a kind of “conservative revolution.” Enemies of the DH are not purists; they are merely pigheaded.

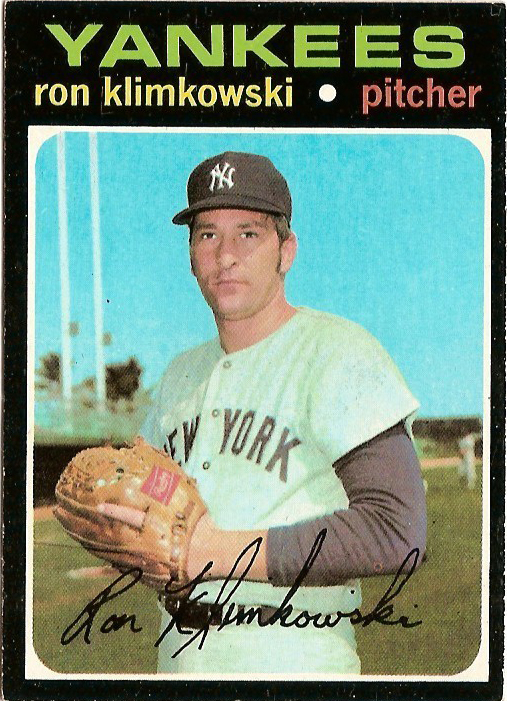

I am of course convinced intellectually by my own argument (why else would I offer it?), but I confess my heart is not fully in it. I used to catch for the New York Yankees. No, that’s not true. I used to catch a New York Yankee. No, that’s rather misleading. I, along with my brother-in-law, used to play catch with Ron Klimkowski, who lived across the street from my sister’s home on Long Island. Ron Klimkowski, pitcher, was a victim of the institution of the designated hitter in the American League. How did that work? When the DH was installed in 1973, logic dictated that a team would not simply promote a bench player to this offensive starting role; rather would look for a player who was an excellent hitter, good enough to be a starting position player in previous years. This meant adding to the pool of position player types, which meant subtracting from the pitching staff at least by one. I well remember the story in the New York Times about the sad fact that Ron Klimkowski, so popular with his teammates, would be cut, the first announced victim, as far as I know, of the DH revolution—and the wrong person to be cut, as I will more than suggest later on.

Ron Klimkowski was handsome in the virile John Wayne mode, although the Slavic cheek bones kept him from looking like a cowboy. He was charming, funny, a delight to be around; there was nothing retiring about him, which was ironically a part of his charm, as when he identified himself on phone calls to his friends as “the Polish Prince.” I say “was” sadly, for Ron died in 2009 at 65, much too early for such a vital person, died of “heart failure” as the obituaries said. Ultimately who doesn’t die of a failing heart? In some sense it was his heart that kept him alive beyond medical expectations.

I met Ron during the 1970s. When my sister and brother-in-law moved from Long Island to Florida at the end of the decade, and I moved briefly to Spain and then to Connecticut, the connection was broken, although my sister and her husband kept in touch with Ron and his wife Donna until the end. The details of his death, slim though they be, I got from Donna by way of my sister. Heart trouble and other attendant horrors drove Ron to the hospital for treatments and ultimately for hospice-like care. There is some suggestion from my sister of medical carelessness, about which I cannot draw any educated conclusions except to note that my sister says that one physician “cursed the hospital out” for Ron’s quick and then irreversible decline. In any case, the physician finally told the family that Ron, in a great deal of pain mental and physical, was alive without any hope because he seemed to be hanging on for all he was worth—that it would be best for him if he could just let go. A sister-in-law, with Ron’s wife’s approval, entered his room and whispered to him something like “Ron honey, you have been a fighter all your life, but it is time to relax and let it happen, time to let go.” I’m not sure whether she was merely thinking out loud or expected to be heard. In any case, Ron opened his eyes, said “Bull shit!” and died. The way I put it is that he died like a Yankee.

For over thirty years (I don’t know why I never told him this), Ron was a “character” in a lecture I gave whenever I offered a particular philosophy course in which one session was devoted to the human effort to overcome the impossible (or at any rate what is judged to be a statistical impossibility). As an example, I talked about Joe DiMaggio’s 1941 streak of hitting safely in 56 straight ballgames, knowing I would have the attention of some students. About how hitting a baseball—which seems such a normal thing to do given the fact (which once upon a time was a fact) that all American boys, and some girls, did it—was perhaps the hardest feat to accomplish in sports with any real consistency, since even the best hitters will fail 70% of the time. (In basketball, for instance, a player who sank only 30% of his shots would not be considered one of the best shooters, indeed would be kicked off the squad.) About how the task is even harder if one is trying to hit major league pitching. About how given these truths, DiMaggios’s streak was an overcoming of the statistically impossible, and so on. And to cap things off, to give some authoritative heft to my lecture, I let the students know that I know what I am talking about because (with personal details) I used to catch the ex-Yankee pitcher, Ron Klimkowski, and “I can tell you that a major league fastball is one hell of a missile.”

Ron did not have an impressive major league career—unless you look closely enough at the figures, and then you end up shaking your head and wondering why he wasn’t there longer. He spent four years up top, three with the Yankees and one with the Oakland Athletics. He was a Red Sox farmhand from 1964 until he became Yankee property through the Elston Howard trade in 1967, and came up to the Yanks late in 1969—earned-run-average or ERA of 0.64 (!) in a three game “cup of coffee.” He spent the full year in New York in 1970 as an all-around reliever and spot-starter (starting three games, one a shut-out); was one man in a two-player trade to Oakland in 1971 for Felipe Alou, relieved for the A’s; in 1972 was repurchased by the Yanks and returned to his spot-starting and relieving role. And then: Jim Ray Hart and Ron Blomberg were designated-hitting for the Yanks the next year, and bye-bye Ron.

His won-lost record of 8-12 is irrelevant for a reliever. And in any case the W-L can be misleading, depending as it often does on luck—meaning presence or absence of offensive and/or defensive support. (In 1936 Van Lingle Mungo with the Brooklyn Dodgers led the league with 238 strike outs and won 18 while losing 19.) Ron’s ERA tells the truer story: 2.90. For the Yankees, it was 2.76. But even ERA can have its limitations as a measurement: scatter enough base hits or walks over nine innings (hell, let’s say 10 or 12) in such a dispersal that rarely is a runner in scoring position, and you’re home free.

But there is one statistic that cannot mislead, one which surprisingly is not often talked about, but which I think is the best measure of a pitcher’s effectiveness: Assume a pitcher is not generous with bases on balls (and Ron walked a man only about once every third inning), how often was he hit? What was the collective batting average against him (AVG or BAA)? The league’s batting average against Ron Klimkowski was a puny .224. Two twenty four! Let me put this in context. There are over 70 pitchers in the Hall of fame. Only six have lower AVGs than Ron: Addie Joss by one point, Nolan Ryan at .204, Sandy Koufax at .205, Hoyt Wilhelm at .216, Ed Walsh at .218, and (wouldn’t you know it!?!) Babe Ruth at .220. With slightly higher AVGs than Ron were Tom Seaver at .226, Walter Johnson at .227, and Bob Gibson, Goose Gossage, and Rube Waddell at .228. You could look it up. (And you would be surprised at how many greats were in the .250s and even higher.)

My beloved Yankees let him go too soon. Of course .224 in only four years is not definitive, but if your head is screwed on right you don’t say “His .224 is only for four years [assuming you’ve noticed it at all] so let’s let him go.” My damned Yankees let him go too soon. I wish I had asked Ron whose decision it was. General Manager Lee McPhail? Manager Ralph Houk? It’s hard to believe an old catcher would be oblivious to a pitcher’s strengths. I’d like to think it was a move by Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, man of erratic opinions, who justified the trade of Jay Buhner to Seattle for Ken Phelps in 1988 by explaining that Phelps could play a little first base (where Don Mattingly was installed) and DH (the Yanks had Jack Clark for that task) and besides could spell Willie Randolph at second (Phelps was left handed!). I prefer it that the ridiculous perform the ridiculous.

Of course it could also be said that Ron was damaged goods by the end of his time in New York . . . with a bum knee. But a knee—given orthopedic technology—need not be fatal to a pitcher, who after all would not be running bases. His arm, his right arm, was still a canon. I know.

Indeed I know. Living in Manhattan, I visited my sister on Long Island often, and neighbor Ron regularly walked over from across the street. Occasionally he would appear with a ball and two gloves. “Sam. Wanna play catch?” “Of course!” Once he walked over with ball, glove, and catcher’s mitt, which he tossed to me. “I played second, never used this thing.” “I can’t find the other glove” he said; “be a sport.” After a few minutes of tossing back and forth I am getting used to the mitt, so I yield to idiocy and crouch down in a catcher’s stance. Ron is easy on me: slow curves and what we called in my youth the straight ball. I am getting very confident, pleased with myself, even cocky; after all, this is the middle 1970s, Ron has been out of baseball a couple of years, no longer pitching in Yankee Stadium, instead selling Cadillacs on Long Island. I am now pretending I’m a bullpen catcher: “Come on Ron. You can throw harder than that.” So Ron does; nothing fancy, just a faster “straight ball.” Then, probably because he sees I am handling his “warm up” adequately, vastly overestimating me, he proposes, “Sam. What d’ y’ think? I’d like to put something on a fastball, see what I’ve got. Think you can handle it?” “No problem. Bring it to me, Prince.”

My mitt is chest high. Ron winds up. The ball is in the pocket of the mitt. I never saw it. Only a blur. Three or four inches either way it might have killed me. Shaken, but covering it up, I toss the mitt to Ron. “That’s enough for today old buddy. Let’s have a beer.”

I would like to claim a terrible irony in the Yankees letting Ron go with the coming of the DH on the grounds that he could swing a bat. His first year in Class A ball he hit a productive .269 with 5 doubles and 7 runs-batted-in in 52 at-bats. Once in Triple A he hit .286. But—you know what I’m going to tell you—he learned how not to. With New York and Oakland he batted .091. So my late friend Ron—whom the Yankees never should have let go as a pitcher—provides an argument for the DH. For the installation of the DH rule, I mean, not a justification for the release of Ron Klimkowski, who as a pitcher was—the statistics do not lie—exceptionally hard for batters to touch. I wish sports historians had a proper sense of who and what my old friend was. My God!—.224. Did no one know?

________________________________

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others.

Help support New English Review here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Samuel Hux, please click here.