My Life as an Object

by Daphne Patai (May 2023)

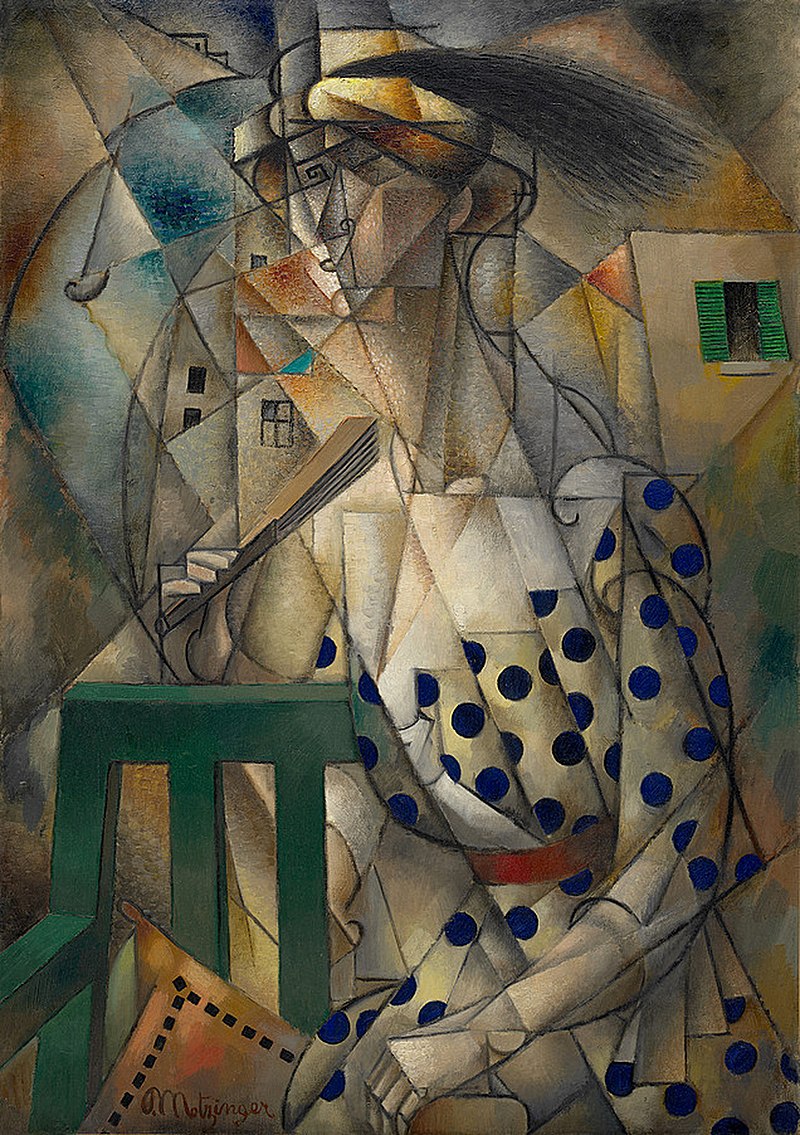

Femme à l’Éventail, Jean Metzinger, 1912

Perched naked in a sling swaying above my bed, I wait for the two aides in this skilled nursing facility—devoted to the care of people with advanced MS and ALS—to push the hoyer lift overhead, carrying me along its ceiling track into the tiled bathroom adjoining my bedroom.

At this point, I usually think of myself as a large sack of potatoes. The humorous aspect of this image is not lost on me, but I can’t laugh or even smile much because the multiple sclerosis that brought me here, which has rendered my legs useless, now affects my mouth and throat too.

Once in the bathroom, the aides—this time they are two women from Haiti—lower me onto a bath chair, remove the sling, arrange my legs, place my feet on the footrests, and proceed to give me a shower. This occurs twice a week. Invariably, at this point I think of myself as a vastly oversized naked baby, minus the charm. On other days they wash me in bed. All of them do an excellent job. I can imagine the administration intoning: the patients must be kept clean!

The administration has also instructed the staff to speak only in English, even to one another, so as not to induce paranoia in the rest of us. One of the aides, on the sly, told me this when I asked why they didn’t speak Creole to one another. So they talk together in very low, guttural, tones—in English, yes, but even so I cannot understand what they say. Still, I approve their dedication to subversion of the rules. Their job is hard, very demanding physically. They bend, stretch, pull, scrub, constantly in motion. With gentleness and infinite patience, they wash me from top to bottom. Has anyone ever washed toes so carefully? Each one gets long seconds of attention. In the shower, they wash my hair, for some reason using excessively large dollops of shampoo and then conditioner, which I reorder online frequently. They rinse me off with the handheld shower head, the water pressure always too weak, but at least the temperature is good.

They then dry me with several of the fresh white towels they’ve brought in, position the sling once more around and under me, pulling it up between my legs, attach it to the bar above, and haul me up again. The hoyer lift takes me back to my bed. The aides are careful to hold my legs, so that my feet clear the mattress. They lower me down and continue to dry my body.

I lie there, feeling now like a beached whale. The aides, ever attentive, apply scented talc (Maja is my current favorite) to my body, along with body lotion if I so desire. But it’s no joke to deal with a large body lying immobile on a bed. It takes two aides to turn me from side to side, which they accomplish by placing one ankle over the other and then pushing me onto my side. I grab the bed rail and hold tight while they finish the body work. Easing me again onto my back, they swaddle me in a pair of briefs—essentially a diaper—and then pull on my slacks. This takes a while. The top is easier to deal with, since I can still stretch out my arms to help guide them through the long sleeves. All my clothing is made of cotton: another gift from MS is hypersensitive skin.

The aides are supposed to do range-of-motion exercises with us, a task they resist. The result is not ten minutes of exercises per weekday; not even five. More like 60 seconds of lackluster motions as I lie in bed: they bend my legs at the knee; fold one leg over the other a few times; massage my toes (this is their favorite). That’s it. Then the hoyer lift routine starts again and I am transferred to my wheelchair for as long as I wish to be “up.” An aide gives me a hairbrush; awkwardly I brush my hair with my good (that is, better) hand. She sprays my favorite cologne (from Brazil) on my neck and wrists. Despite the aides’ efforts to smooth out my clothes and make me presentable, even after all that the result is far from satisfactory.

Elegance, style, grace—if ever I had them– are long gone. People in wheelchairs have a characteristic slouch, bellies protruding, shoulders drooping. Good posture, along with well-draped clothing, has left the building. My torso lists toward the left, so an aide rolls up a sheet and stuffs it against my left side in the wheelchair, which helps for a while. I am impressed that some women here still bother to get their hair colored and styled in the “spa” downstairs. Will they do that forever? I go only for an occasional haircut and nail clipping, when necessary.

For many years in my old life, collecting life stories was one of my favorite activities as a researcher and writer. Oral history (as taping life stories is called) was a major feature of several of my books. In Brazil, forty years ago, I ran around Rio and Recife with a large Panasonic recorder, conducting sixty detailed interviews with women of diverse classes, races, and walks of life. Surprised at first by how eager they were to tell me their life stories, I soon understood that narrating one’s life is indistinguishable from what I came to call “constructing a self.”

Here in my new life, amid a group of people who surely have stories to tell, I have again felt the lure of the other side of speaking: listening. I have no doubt the residents here have much to communicate. But there are two small obstacles: me and them. My speech is shot, reduced to semi-comprehensible phrases and slow rasping sounds. The other residents’ speech is in various stages of existence; several sound perfectly normal. Among the many other things I’d like to ask my housemates are: What were you “before?” And what has been your biggest loss since moving here?

My own very defective speech makes that simple goal almost impossible. It would be too laborious to explain to them that this is no casual curiosity of mine. Why should they entrust their precious words to someone who cannot utter even one simple sentence succinctly and clearly?

Then there are the ALS patients upstairs, on ventilators, unable to speak at all. I’d like to know what keeps them going, but that’s too hard a question to expect them to answer with their eyes picking out letters on their computers. An attractive young woman with Huntington’s disease must also have an interesting story to tell—and she can still speak reasonably well, with effort, though her disease causes her entire body to twitch and flail about, non-stop. Just watching her for thirty seconds exhausts me, and I can only imagine what it feels like to her.

I no longer take offense when people in the outside world, hearing my speech for the first time, presume I am deaf and probably mentally retarded. hey can’t help it. I don’t believe we are programmed, as a species, to be mean, but the sad fact is that having a visible disability does not make us immune to others’ routine expectations of normalcy, or to judgments about its absence. Similarly, it doesn’t spare us from the unacknowledged games of compare-and-contrast that so plague group interactions. We are, for good and ill, stuck in our own skin, our own individual nervous systems. I accept this because I have no choice.

Of all the losses imposed by neurological diseases, the one I have found most devastating is not, as some might suppose, the loss of mobility. Nor even the predictable problems with bladder and bowels. These, despite being linked to our sense of “dignity” —no doubt a result of the trauma of toilet training—do not necessarily attack one’s sense of self.

For the vast majority of us, selfhood is expressed to the world above all through our speech. It’s this that connects us to others, that lets us know and be known. And that loss—in my case after forty years as a professor, lecturer, punster, lover of words—has been profound. It is an assault that sent the old me scurrying within, leading to my near silence.

To my great good fortune, my mind still works, as do my eyes and ears; and to my great ill fortune, this means that every single day, after cohabiting with my inner self, still chatting internally at top speed, I must face reality: the shock of hearing my speech not as it stubbornly exists in my mind, expressive and agile, but as it imposes itself on the outside world—nasally, whiny, slow, difficult or impossible to comprehend, accompanied by lips that move too much, no longer sure of how to position themselves. Altogether unlike the self I was, or thought I was, for almost a lifetime.

But that was then; this is now. What emerges now when I try to speak is always lacking in nuance, subtlety, irony, fluency, musicality. Eating, too, has become a messy activity: I don’t like to go to the dining room. Several residents do take their meals there, as does one woman who is fed by a nurse through a tube in her stomach. Like most all the aides, the nurses (always available if we call for them) are kind and patient. Once I stopped lamenting my situation and looked around, I realized that we few (100 patients over six floors) are the lucky ones, having landed in a high-quality facility.

For some months after I started living here a year and a half ago, I puzzled over the set expressions on the faces of the other residents. There are ten of us in each “house,” occupying ten single rooms with baths, arranged around a good-sized living room, dining room, and kitchen. There is a plaque on one wall in the living room with the names and dates of several dozen people who lived and died in this house. I read their names and wonder about their lives.

Even now I don’t know the names of all my housemates, but I cross paths with some of them as we ride around the common areas in our wheelchairs, speed set at slow, indoors.

At first, for a long time, I thought of their faces as conveying the expressions acquired from institutional living, not revealing much, letting nothing in. Now I know better. As our eyes briefly meet, I sense them quietly saying, as do I constantly, “Don’t imagine for a moment that I think this is all right.”

Sometimes, not often, I glimpse a smile breaking through the expressions most of us park on our faces as we roam about in our wheelchairs. And I remember my husband, my love, casting the mere hint of a smile toward me as he sits across the table at a dinner party. I know that smile. It means, “I can’t wait to be alone with you again.”

Then, jolted back into my skilled nursing facility, inhabiting the disabled body my husband did not live long enough to see, though he knew it might well arrive, I look around at the other patients. They sit, as always, unmoving, staring at the large TV screen in the dining room, or slumped, heads bowed, asleep in their chairs, or going downstairs in the elevator to sit outside in the garden on a nice day, or taking a break (in the case of my angry neighbor) from shouting about fuckin’ this or that. I try to tune all this out and think, instead, of the time “before,” when we led lives in the world.

Suddenly my life as an object is turned on its head. I recall then the delicious, vibrant feeling of being a different kind of object, changing through the years, inevitably, but always, seen through the eyes of love, an object of desire.

Table of Contents

Daphne Patai, Professor Emerita at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she taught in the Languages, Literature, and Cultures Department, is the author and editor of ten books and numerous articles on utopian studies, feminism, free speech, and higher education.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast