by Mark Satin (November 2024)

I was handing out “Jill Stein for President 2024” leaflets on a decrepit stretch of Telegraph Avenue here in Oakland, California, when I saw something that broke my heart. The sign over “Goldfarb’s Pawn Shoppe” had been changed to read, “People’s Pawn Shop / Under New Management.” Goldfarb’s shop, or “shoppe” as he insisted on spelling it, had been a beloved part of the lower Telegraph community for decades, and I’d gotten to know Goldfarb well.

He wasn’t anyone I’d have chosen to know. About four years ago, his display window caught my eye. Along with bizarre stuff like an ancient violin and a giant Bible, it featured items that ordinary people might want, such as digital devices and some pretty nice kitchenware and clothes. And you could see through the window that the place was full of ordinary people, exactly the kind I wanted to reach through my political organizing with the Green Party and Democratic Socialists of America and Black Lives Matter and CODEPINK.

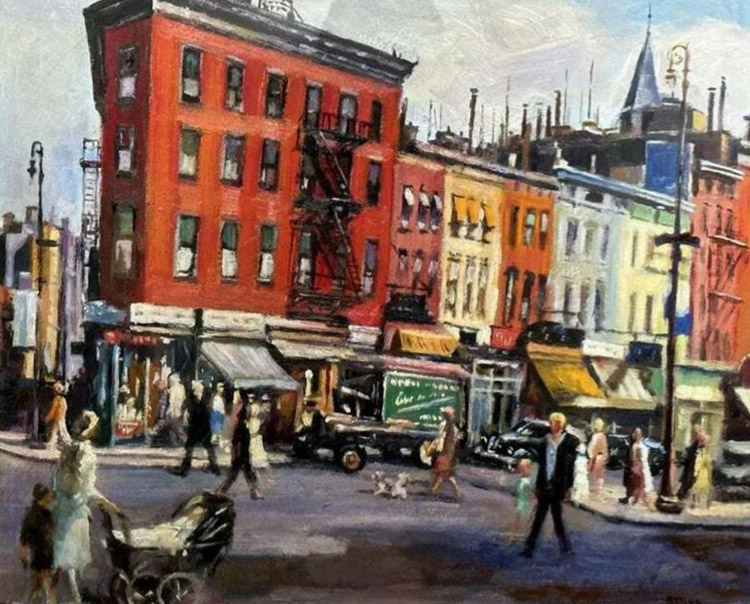

So I wandered in, and spotted Goldfarb right away. What a relic! He was sitting in an overstuffed armchair behind the cash register woman, reading Commentary magazine under a dim floor lamp. Violin music was coming from an old-fashioned record player nearby. The melody sounded vaguely familiar; I used to love violin music as a boy, until rap music and radical political theory introduced me to a bold new world. High above the cash register you could see framed photos of the neighborhood as it looked in the 1950s, before its alleged decline.

Goldfarb saw me staring at him and struggled to his feet. He squinted, and I was sure he was trying to determine my skin color. “So you’re here to sell?” he finally said.

I told him the truth—curiosity drew me in—but he warmed up considerably, as I knew he would, once I told him my parents were Jewish. “I was born in ’38 and moved here with my new bride 19 years later,” he wanted me to know. “Both of us had grown up in Brooklyn, on Avenue N, and we’d never been more than a hundred miles from Avenue N in our lives. But we wanted to make a new life for ourselves, an American life—that’s the way young people were in those days—so we took the train west, knowing no one. My wife had heard that Oakland was San Francisco’s Brooklyn, and that was good enough for me.”

Boring old Jew, I thought. But I tried to relate to him, since I knew I’d need his permission if I wanted to hand out leaflets and talk to customers on a regular basis in his awesome store. “I decided to live an authentic life too,” I replied. “I dropped out of Cal State East Bay to do political organizing after the police killed Michael Brown in 2014—you know, “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” —okay, it didn’t really happen that way, but a lot of us felt that it could have. Anyway, after dropping out I never looked back. Worked in the cheese section at Whole Foods here ‘till they fired me for wearing a Black Lives Matter T-shirt, stayed on unemployment for as long as I could, then one of my activist friends sent me to a shrink in Berkeley who told Social Security Disability that I’m ‘psychologically incapable’ of working. So I’m a full-time revolutionary now, hooray!”

“Oy, one of those,” he said.

“Yep,” I said, “and proud of it! My artist father’s gone—ran off with my mother’s best friend when I was a kid—and after that Mom wanted me to grow up to be a total straight arrow, engineer or social worker or even a cop! And get married and have kids and a 30-year mortgage! But I insisted on being real.”

I had said those exact same things to my radical friends dozens of times, always with pride. It felt weirdly different saying them to Goldfarb. I looked down at the floor, saw my battered old sneakers. Seeing them reminded me that I’m living my life not to accumulate power and privilege, but to help create a magnificent revolution for us all.

Goldfarb hadn’t noticed my reverie and was yapping away. “I escaped the academy for more traditional reasons,” he was saying. “We arrive in Oakland, and immediately we discover that my beautiful Pauline is carrying a child. So what’s a man to do? Ephesians says husbands and wives should give their lives to each other. Should die to and for each other, even. So I disappear my dream of attending Berkeley or Stanford, and go into my father’s old business, which I knew I’d be good at—pawn brokerage.”

“Well, not everybody gets to spread their wings and fly,” I said, echoing a Beatles song I was sure he didn’t know.

I was too afraid of sounding micro-aggressive to ask Goldfarb about his nose, easily the most hideous bulbous beak I’d ever seen. But he broached the subject himself. “The shoppe finally opens,” he said, “and we are terrified. We’re peddling our wares in a sea of Christianity, an ocean of goyim! My darling Paulie convinces me to have plastic surgery on my nose, to keep from alienating potential customers. So we approach plastic surgeons all over the Bay Area, but can’t even begin to afford them.”

Goldfarb got up in order to handle a customer with a major purchase, and I couldn’t help noticing that he pocketed the payment. The government wouldn’t be able to collect taxes on it! I was shocked, appalled, fascinated. Then he returned to me without skipping a beat. “So I say to Paulie, look, Oakland is filling up with schvartzes and Mexicans, so it’s important for store owners here to look like tough guys. And I do look like a tough guy with this schnoz … don’t I?”

I swallowed my politics and assured him that he did.

I had to admit, Goldfarb intrigued me. I’d never made friends with a business person before. And he was happy to let me hang out at his “shoppe” every month or two, passing out political leaflets and trying to strike up conversations with what I felt were “real people.” Eventually I met Mrs. Goldfarb, and their two adult daughters—the only two people he’d allow on the cash register. All three of them called him simply “Goldfarb,” and all of them doted on him though I couldn’t understand why. It was clear to me he exploited them all sub-consciously, and even consciously.

***

The pawn shoppe ran on a remarkably even keel. The record player always played classical music, Goldfarb always devoured highbrow conservative magazines in his armchair, and Mrs. Goldfarb always brought him a homemade sandwich for lunch. Although I visited there—always with my leaflets—only six to 10 times a year, it began to feel like my second home, or at least a stable intact bourgeois home that was glad to take me in.

So I was startled to see a dramatic new presence there toward the end of 2023. An enormous wire mesh net had been hung on hooks beneath the ceiling. It stretched from wall to wall.

“Is that your idea of a Christmas display?” I asked Goldfarb.

“How can a retired cheesemeister who is a passionate supporter of our black-racist D.A. and our progressive city council be so clueless?” he said. “For the last half year, goyim have been sneaking in through the roof at night and stealing my goods—wrecking our livelihood! It is a tragedy. We’ve been here forever, and there’s been tsuris before, but this is different; a new level of sickness.”

“Big cities may be ungovernable today,” I said, repeating a line from my activist friends.

Goldfarb put a wrinkled hand on my shoulder and pulled me close. “Every night when I go home,” he whispered, “I electrify that net. See those ridiculous ‘dream catchers’ there? Well, this is my nightmare catcher!”

I am a humanities guy; I didn’t get how dangerous Goldfarb’s contraption was. Plus his breath stank of lox and onions, probably from a sandwich Mrs. Goldfarb had fixed him. Fleetingly, and despite 12 years of reading radical-feminist, separatist-feminist, and postcolonial-feminist texts, I wished I had someone at my tiny apartment who’d make sandwiches for me. Or anyone there, period. “Has it occurred to you to call the police?” I said. “Even I’d call the police if my store was being robbed all the time.”

“I did call the cops last month, and they came over, a man and a woman both. But when I showed them a fresh hole in the ceiling they just laughed. ‘We can’t even deal with all the murders, rapes, and armed robberies in this town,’ the man cop said. ‘Anyway, we catch this kid, he’ll be back on the street a few days later and might come looking for you. So I wouldn’t even file a complaint, old buddy.’ The shiksa then offered me a cookie.”

“What kind of cookie?” I blurted out.

Goldfarb straightened himself up to his full height, probably five-foot-four in his stiff leather shoes. “I wouldn’t know. I refused it,” he said.

I couldn’t help myself—I raised my fist and gave him a giant “YESSS!” I was genuinely appalled that he felt and was so helpless, even though I knew my fellow activists would tell me not to shed “white tears” for him.

***

I only visited Goldfarb’s shoppe a couple more times before seeing the change-of-management sign. Although I was doing important Green Party work that day, I had to run in to find out what happened.

Everything felt strange inside; my home-away-from-home had been leveled, shadow-banned, blown away. The electric mesh net was gone, the overstuffed armchair too. The photos of the old neighborhood had been replaced by larger-than-life posters of Huey Newton, Angela Davis, and Frantz Fanon. They’d been heroes of mine since my first year at Cal State, but they seemed vaguely menacing now. The record player had been replaced by a boombox, which was loudly playing one of my favorite hip-hop songs, N.W.A.’s classic “Fuck Tha Police.” But it sounded stupid now. The new manager shouted over to me, “You want to sell me something, boss?”

When I heard “boss,” I felt punched in the gut. Didn’t my sneakers and jeans and Jill Stein hoodie establish that I was one of us? “Where’s Goldfarb?” I said.

“That old Jew? He was a bad man, ripped off the neighborhood, ripped off the tax collectors, finally killed somebody and they took him away. His kids and the city and a couple nonprofits gave me a nice little package in exchange for running this dump.” The manager’s head bobbed and weaved to N.W.A.’s chilling lyrics. I tried to remember why I’d stopped listening to violin music as a boy. “He’s at the county jail, but you don’t want to visit him, boss. It took the police a week to get his smell out of here.”

I left as soon as I politely could, and rode the bus to the Alameda County jail. All I felt was numb.

***

“Goldfarb! Are you here to sell?” I said after they led me to the visiting area, and I tried to laugh. “Welcome to ground zero of the carceral state!”

He stared at me fiercely—or as fiercely as one can in an orange jumpsuit. “Ah, my little cheesemeister,” he said, “here to wish me goodbye and good riddance, like a man at his father’s deathbed. Fair enough. Remember that electric mesh net?”

“It’s gone now,” I said.

“Nu? It did its job. Early this year, one of Oakland’s many enterprising young men, a schvartze, broke through my roof, lowered himself onto the net, and fried there.”

“Good God!” I said.

“When I saw him dead the next morning, I unhooked one end of the net and he slid to the floor. Then I said a little prayer for him, crammed him into a black plastic bag, and schlepped him to the Gaza Flip—what you call the dumpster.”

“How could you?” I said. “Not one ounce of compassion!”

“Oh, grow up!” he said. “Every mamzer that robs a store commits, on the average, 35 other robberies, rapes, muggings, and what have you. So I maybe saved 35 people from traumas that would have haunted them the rest of their lives. Doesn’t that count for anything in your world?”

I couldn’t think of anything to say.

“Boychik, have you ever read the Old Testament?” he said.

I promised Goldfarb I’d read Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Joshua, but I didn’t mean it. I just wanted him to get on with his story.

He grabbed hold of a jail bar. “A couple months later,” he said, “another young man dropped in, a Mexican. This time one of my daughters schlepped him to Gaza. She’s like you—she wanted the ‘experience.’”

“But I’d never do anything like that!” I said.

“Of course you wouldn’t!” he said. “That’s why you’re totally ineffectual, the schlemiel of north Oakland, with your Jill Stein leaflets and your CODEPINK water bottle. You think nations endure because of kindness, or forgiveness, or ‘multicultural understanding.’ Nothing could be further from the truth.”

“I do not believe in the concept of ‘the truth,’” I said. I’d taken a course on postmodern literature at Cal State, and it had left a deep impression on me.

“Mrs. Goldfarb is dead,” he said. “Will you recognize that truth?”

“I—I’m shocked. I am truly sorry.”

“About a month ago now, she was attacked on the street, one block from the shoppe. She was bringing me a chopped liver sandwich from home. With my favorite mustard on it.” Goldfarb wheezed and gasped for breath. “Five kids ran up behind her at full speed, and one of them rammed her with his shoulder, and she hit the sidewalk hard. An 85-year-old woman. And they all kept running.”

I stood there speechless.

“They just kept going! They ran away, at least one of them a girl! As if they were taking revenge! Meanwhile, praise God, somebody called to get my Paulie to the hospital, and for three days she lay there, whimpering and moaning, with tubes coming out of her. Every day I brought her sandwiches, which she could not eat. Every day I told her she was the most beautiful girl in the world. But it was no use. She died.”

Tears began rolling down my cheeks.

“They’ll never identify those kids,” he shouted, “and even if they do they’ll never properly punish them! They believe in ‘compassion,’ just like you.” Goldfarb spat at my feet.

“I really think you should try taking a more Buddhist approach to all this,” I said.

“She was my wife, you son of a bitch.”

We were both silent for a while.

“Two weeks after she died,” he finally said, “a third young man fell into my net. When I looked up, I felt I was seeing a personification of the evil that’s stalking this land—the dopey face frozen in an expression of rage and entitlement, the $300 tennis shoes, the long knife unbuttoned in its sheath, ready to strike, even the crack in the tukhus. And the no-goodnik was white, what they call on the street a ‘wigger.’ I never had anything like his shoes on Avenue N growing up. Why the hatred? Why the resentment? Why?”

Goldfarb’s eyes began tearing up. I wanted to comfort him, but couldn’t think of anything to say that wouldn’t violate my political convictions.

Goldfarb dabbed his eyes with toilet paper from the pocket of his jumpsuit. “So I say to myself, look, Abram, you’re 86 years old, Paulie is dead, maybe it’s time for you to make a statement. And in that wigger I had my statement, a perfect symbol of American ambition today—not for excellence, or knowledge, or even to do something useful like run a pawn shop, but only to take, take, take from other people.”

“And from the environment,” I murmured.

“And from future generations,” he said. “So I decided to leave the wigger up there. It would be my first and only work of art, hopefully a one-hit wonder—an example of ‘found art,’ a genre that goes all the way back to Marcel Duchamp’s urinal. Today it might also be categorized as ‘trash art.’ Anyway, I did leave him up for my customers. I wanted to make them think about and feel what’s wrong with us today.”

“You are completely mad,” I said, but with less conviction than I’d intended.

Goldfarb allowed himself a prideful smile. “Dozens of customers talked with me about my art and what it represented. We had wonderful talks about it, a lot deeper than we could have had at Stanford or Berkeley.”

“They’d have canceled you for sure,” I muttered.

“And you know what?” he said, his eyes tearing up again. “For two whole days, not one of my customers turned me in! Only on the third day did somebody call the cops—and by then the death stink had ruined the ambience.”

The world began to spin. “I’ve got to go now, Goldfarb. Shalom.”

“Don’t you see, dear boy? In their heart of hearts, even the residents of that godforsaken neighborhood know we can’t live in a country without laws and standards based on God’s commands, and men who can enforce them. There is hope, my boy, there is hope.”

I said nothing. I desperately wanted him to let me go.

“And you give me hope,” he said. “God forgive me for saying this, but you are the closest thing I have to a son. Another imperfect father for you, just what you need. But one who knows that behind your meshugenah politics is a good heart and a deep soul. So please, I beg you, stop trying to save the world with your fake friends and be who you are for a change. That is the way you will make the world better. The only way.” Then Goldfarb chuckled and sang, in a creaky voice that was totally off-key, “Take your broken wings and learn to fly!” Then he sort of scowled and said, “You’re almost thirty, schmendrick. Get out of here. Gey avec.”

I could not speak. I wanted to hug him and slug him, both, so I took his advice and simply turned and left. He was racist and sexist, ethnocentric to the core, petty-bourgeois to the core, a highbrow wannabe, and a real Bible-thumper. And now I knew he cared more about his property and the welfare of his family than he did about the three young men he killed, including two people of color.

But when I tried going back to my Green work that day, I found that I couldn’t. So I called in sick. I told them it was COVID, knowing that that would buy me as much time away as I needed.

That night I couldn’t sleep, so I turned on YouTube and listened to some of the violin music I used to love before my birth father ran away. I hadn’t listened to any of that stuff for two decades. I played the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto over and over, each time with a different violinist.

And the next day, I bought a cheap Bible at a used bookstore, and read Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Ephesians. I was amazed to find them all so understandable!

And the day after that, one week before the 2024 Presidential election, I visited my old Berkeley shrink and pleaded with him to tell Social Security Disability that I was no longer “psychologically incapable” of working. After only a couple of minutes with me, he agreed to do so immediately.

And the day of the election, after a big delicious breakfast, I downloaded the “Police Officer Trainee (197D) Application” from the website of the Oakland Police Department.

I stared at it for the longest time, feeling calmer and more collected than at any time I could remember. Then came tears of joy. It was as if the revolution I longed for had finally happened.

Table of Contents

Mark Satin is the author of Up From Socialism: My 60-Year Search for a Healing New Radical Politics (Bombardier Books, distributed by Simon & Schuster, 2023), which was reviewed on The Iconoclast earlier this year, by Bruce Bawer. Mark’s personal essays “Another Idealistic Lefty Bites the Dust” and “My Super-Woke Ideas Helped Kill My Former Girlfriend” were published this year on The American Spectator website, https://spectator.org/author/marksatin/

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

One Response

Dazzling, sparkling tears.

Heart not broken, just deeply dented. Now must pound it, almost perfectly, back into shape.