New Year’s Eve

by Kirby Olson (March 2020)

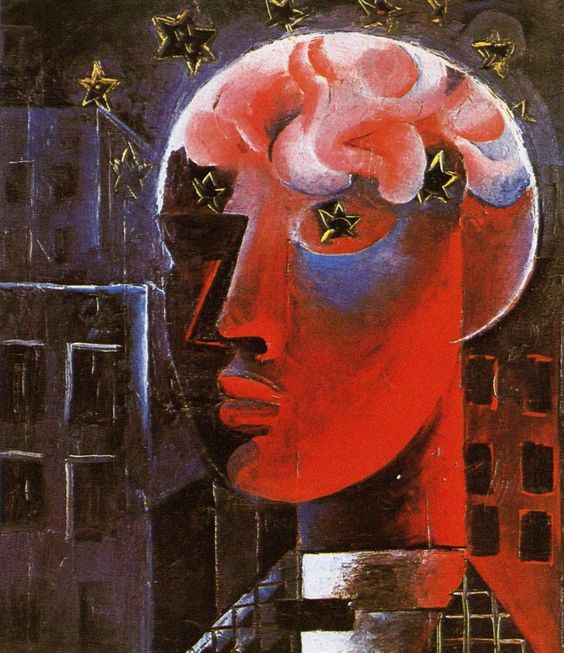

Roter Kopf, Otto Dix, 1919

The box was full of DVDs from my mother. While the kid watched an old version of Dumbo, I got on the phone and went through the messages. There was a message from the bank that said that the check for twenty-five thousand had bounced. At least we hadn’t bought the IKEA table.

Dumbo was about an elephant with huge ears ridiculed by a whole circus. The mother elephant gets mad that her son is ridiculed and attacks the other elephants. She is put in an asylum. A mouse befriends the lonely baby elephant and they get drunk. While drunk, it is discovered that Dumbo’s ears have the magical property of acting as functional wings. Dumbo becomes the star of the circus. Dumbo’s mother is reunited with Dumbo when he turns out to be a success. Where was the father?

It was New Year’s Eve, so Falstaff and I drove down to Oneonta. The whole town was having a children’s festival. We went into the YMCA where a puppet show was offered. The price was ten dollars per person. Falstaff and I looked at one another. We had to leave the line, and get back in the car. Falstaff cried, as he had been promised the puppet show. I called Mari on the cell. Mari promised him something good to eat. We went over to the Wal-Mart and shopped with WIC checks. We drove home in a blizzard.

I was afraid to go more than 40 mph. All the way home past the ramshackle barns and the wintry white invested over the fields and homes and lakes and trees, I thought about how to break the news that the check had bounced. Why had it bounced?

“Mari, Dali’s second check bounced.” I blurted.

“Good,” she said. “They can keep their money, and we can keep the baby.”

She was quiet as we wended our way through the western Catskills toward our rental.

“Everything’s wrong.” Mari noted.

“Our kids are in one piece.” I reminded her. “The universe is intact.”

I spent the evening repairing the downstairs shower. The bottom of the door leaked so I had bought some caulking tape and some caulk at Wal-Mart. In a few minutes, I neatly sealed the bottom of the door on two sides with the caulking tape and then dabbed the caulk around the ends. I rarely repaired anything so I was excited to see if this would fix the shower’s leak. I then repaired the seal at the bottom of the garage door with another piece.

Upstairs the kid was watching Dumbo again and eating WIC-approved cheese and cereal. The Christmas lights twinkled. The movie was even better the second time, and our child was happy. After the movie, I played monster with him. I took off my glasses and grabbed his arms or legs and pretended I was going to eat him. Falstaff realized that if he pried my thumb loose he could escape.

The kid went to bed after wash-up and said as I tucked him in, “Dad, I think mommy forgot to give me my dinner.”

There wasn’t any dinner-type food until the following Wednesday. He fell asleep, and I went downstairs to ride the stationary bicycle. My wife remained upstairs reading a book called Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women? (PUP 1999) sent by a friend, Ulna.

An hour later, I was sweating from the stationary bicycle, when Mari appeared in the doorway with a hand on her hip.

“Norm,” she said. “Have you got a minute? Author Susan Moller Okin argues that Judaism, Christianity and Islam should be wiped off the face of the earth to make room for secular feminism. She particularly wants to destroy Judaism and Christianity. Even Adolf Eichmann didn’t manage that.”

I wasn’t in the mood.

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

She said, “Secular humanists like Okin would cast all Christians and Jews into the gas chambers of history,” Mari said. “Do something.”

She closed the door, and went back upstairs. I glanced at my watch.

The ball was about to drop in New York City so I brushed my teeth, took a couple of sleeping pills and ran up the steps to kiss Mari. I was fifteen seconds late. Mari was reading the book and drawing red lines under certain passages. Helena was fast asleep with a pink cap on her head. I watched the TV. Confetti was blowing through Times Square as a million people thronged the capital to usher in a New Year. I was so glad I wasn’t there. I hate the cold, I hate loud noises, and I hate crowds. We snapped off the set and went to bed. I dreamed that the skyscrapers of New York City were in actuality the heads of Easter Island and that the great wall of China was in actuality the white picket fence of Huck Finn, and that the canyons of Colorado were the cathedrals of France.

I got up and wondered if Mari hadn’t been too hard on Susan Moller Okin. I had read her essay. It was written with clarity and force for women’s rights even if it seemed to me that she knocked several thousand years of religious culture off the table in order to clear a space for secular feminism. Mari took the book back from me.

She popped a couple of chocolate covered cherries to balance her anticipated disgust.

“Norm,” she said. “There is more freedom among the Ashkenazi Jewish women that Okin despises than among the secular feminists. Feminists want to work 14-hour days making as much money as male CEO’s. What about children’s rights? Lutheran women work as Sunday School teachers and on Saturday as Girl Scout leaders. Women like Okin put their children into daycare the month after childbirth and go right back to the office and see their children a few hours on weekends. Are children a second thought for them? Are you even listening?”

“Mari, I have read the essay. I didn’t like it either. We have the first amendment in this country. That woman can squeak all she wants. That’s what Democrats do. Why don’t you turn Republican?”

“In National Socialist Germany they murdered Christians and Jews,” Mari went on. “In Vietnam they are killing Christians. In China they are forcing Christians into work camps. In Tibet, the communists are killing Buddhists. In North Korea, they behead Christians. How many more hundreds of millions of religious people have to die before the socialists stop butchering our people?” She asked.

I shrugged my shoulders. What would it be like if Helena died and it was just Mari and Falstaff and I again? We would drive over to Woodland Cemetery and drive up to the hilltop where she would be buried. Mari would insist that we make regular visits. I would put white roses on Helena’s grave. She was already part of our family.

“Dad,” Falstaff said. “What are you thinking about?”

In my head, I remained at Helena’s grave. Mari said a prayer while kneeling in the snow. Then she took my hand.

“Dad?”

It was Falstaff, holding my hand.

“What do you want?” I asked, disturbed by his presence.

He came into my office with a coloring book in which he had drawn three different kinds of ice cream and he asked which I preferred. I kissed him, and said the green kind.

“Mom,” Falstaff yelled up the steps. “Mark down the green kind for daddy.”

Falstaff bounded up the steps. I hit the shower. When I came out, I was chagrined to see water seeping out. The caulking job hadn’t worked.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast