by Pedro Blas González (September 2020)

Aphorism, Kurt Schwitters, 1923

In a century when advertising media broadcasts infinite nonsense, the cultured man cannot be defined on what he knows but on what he does not know.[1] —Nicolás Gómez-Dávila

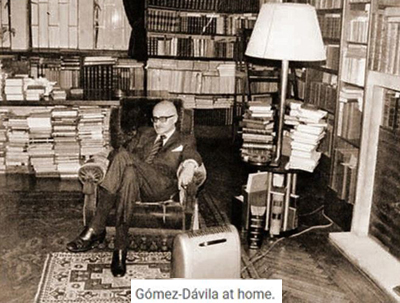

The Colombian philosopher Nicolás Gómez-Dávila (1913-1994) defies easy classification, at least based on postmodern academic ideas of what a thinker should be.

A gifted writer, Gómez-Dávila has only recently garnered a much-deserved reputation as a no-nonsense thinker, albeit long overdue.

Postmodernism does not reward the toil of intellectually honest and independent thinkers. One of the staple characteristics of perennial philosophy is independence of thought from social-political coercion. This requires honesty, and in today’s cultural milieu, also courage. These qualities abound in the thought of Gómez-Dávila, who is an exponent of common sense.

Gómez-Dávila’s elegant and insightful aphorisms and essays are the perfect antidote for academese, a cryptic social-political language that enables its practitioners to safely engage in groupthink and be praised for their ingenious intellectual calisthenics. Gómez-Dávila eschews contrived social-political categories that befuddle thought and the history of philosophy.

Independent thinkers like Gómez-Dávila, who are considered outsiders according to the rules of engagement of the social-political academic clique, view the pedantic pretensions of academese lingo as the child’s play of careerists, not bona fide thought.

Scholia to an Implicit Text is a poignant book of aphorisms in the tradition of aphorists like La Rochefoucauld and Baltasar Gracián. Gómez-Dávila’s writing displays his aversion to postmodernism’s jargon fetish, when the whole point of philosophical reflection is to find coherence and meaning in human existence through prescience and perspicuity. These are some of the fundamental characteristics of enlightened thought that deliver lasting heuristic lessons to man.

Also not lost on Gómez-Dávila’s perspicuity about the nature of philosophy is that for heuristic lessons to leave a lasting legacy, the truths conveyed must be universal and apolitical.

Why waste vital energy on popular causes that man quickly discard in tune with current fashion? This is the charge that Socrates levelled against the relativist Euthyphro. Socrates recognized that Euthyphro’s gods and men, both relying heavily on their passionate whims to explain the nature of piety, readily found themselves waring with each other over their relative values. Ancient sophism, what we today call relativism, is responsible for the failure of postmodern academic philosophy to convey universal truths to thoughtful people.

Why waste vital energy on popular causes that man quickly discard in tune with current fashion? This is the charge that Socrates levelled against the relativist Euthyphro. Socrates recognized that Euthyphro’s gods and men, both relying heavily on their passionate whims to explain the nature of piety, readily found themselves waring with each other over their relative values. Ancient sophism, what we today call relativism, is responsible for the failure of postmodern academic philosophy to convey universal truths to thoughtful people.

Gómez-Dávila sheds much needed light on the vacuity of postmodern thought and what this means to the future of human liberty. His writing creates a buffer zone for thought to flourish unencumbered by the ominous social-political agenda of postmodernity. Philosophical reflection cannot articulate coherence in human experience, much less address fundamental aspects of human reality, by becoming the mouthpiece of totalitarian ideology.

One litmus test of honest philosophical reflection is the absence of fear when embracing the pursuit of truth. To show allegiance for truth, thinkers must be willing to follow its lead, wherever it takes them. This is the strength and refreshing scope of Gómez-Dávila’s intellectual and cultural independence.

Part of the problem that thinkers like Gómez-Dávila identify in postmodernism is the latter’s incapacity to identify and confront difficult truths. It is not in the best interest of postmodernism’s social-political program to promote a stoic perspective of human reality to man. That is, the embrace of human existence as resistance to relative values goes against the core of postmodernism’s promotion of social-political nihilism. While embracing nihilism, postmodernity can ascertain dominance over the role that Christianity and Western values have traditionally exerted over Western culture; two visions of man that must be levelled in the interest of Marxist hegemony.

To read Gómez-Dávila is to understand the broad-ranging sphere of postmodernity and its successful corruption of man’s capacity for self-reflection. Gómez-Dávila puts in perspective how much of postmodern life is the creation of debased, self-promoting nihilists.

If calling attention to the corruption of every man’s capacity to think for himself is Gómez-Dávila’s greatest contribution to philosophy, it becomes easy to realize that his heroic act is a preparation, a propaedeutic for human thought to flourish once again in the future.

Prescient readers recognize that to level vacuous and disparaging accusations at Gómez-Dávila as reactionary is proof that he has duly identified the cancer that is currently consuming the hapless organism of Western values. He writes: “A reactionary does not long for the vain restoration of the past but for the unlikely breach between the future and this sordid present.”[2]

By definition, aphorisms require precision and accuracy, both the long-range vision of thoughtful people. Aphorists like Gómez-Dávila cannot afford the luxury of prosaic systematizers and other essayists. For aphorisms to flourish as insightful purveyors of human reality, thinkers must focus their intellectual acuity on universal aspects of singular targets. Man’s fickle passions are subject to change – not the objective, universal truths he uncovers.

A telling paradox of aphorisms is that they can be considered the beginning of reflection. This is because aphorisms present readers with a cornel of truth that must be developed to fruition. Thus, from a thinker’s perspective, aphorisms are the end result of a line of thinking that only commits its conclusion to paper. Every aphorism that a thinker conceives and writes down is fitted, like a puzzle piece, into the broader structure of truth. A single aphorism alerts us to a particular aspect of truth, while a series makes up the tapestry of understanding. [3]

Because individual aphorisms give the impression of only addressing particular aspects of human reality, their expansive breadth is felt as a cascade of knowledge that completes an essay. While essays move slowly toward a conclusion, aphorisms begin with one conclusion at a time. It is not difficult to see why aphorisms are custom built for the thought process and temperament of reflective thinkers.

Gómez-Dávila suggests that his aphorisms are like the individual brush strokes that make a painting: “The reader will not find aphorism in these pages. My brief sentences are but the chromatic touches of a ‘pointilliste’ composition.” [4]

Consider the intellectual and cultural acumen of the following Gómez-Dávila aphorisms from Scholia to an Implicit Text:

Objective Human Reality: “Men shift ideas less than ideas trade disguises. During the course of centuries, identical voices dialogue.”

Meaning and Purpose: “Everything is trivial if the universe is not engaged in a metaphysical adventure.”

Human Existence vs. Biological Life: “Only he who observes, ponders, and speak it, lives his life – the rest are just lived by their lives.”

The Hierarchy of Values: “When hierarchies yield, appetites rule both in society and in our soul.”

Tradition, Modernity and Ignorance: “Modern is the man who forgets what man knows about man.”

Nihilism and Postmodernism: “Swimming against the tide is no folly if the waters flow towards a waterfall.”

Civilization: “Civilised individuals are not the result of a civilization but its cause.”

Modernity and the Soul: “For he who lives in the modern world, it is not only difficult to believe in the immortality of the soul but also in its mere existence.”

Noble Individuality: “The only possible progress is the inner progress of each individual. A process that comes to a halt with the end of each life.”

Aphorisms are patient and confident statements of truth. Patient, because they communicate tireless truths that have already been vindicated by the passage of time; confident, because they address thoughtful individuals who do not need arm-twisting for their acceptance.

[1] Nicolás Gómez-Dávila, Scholia to an Implicit Text. (Bogota, Colombia: Villegas Editores, 2013), 89

[2] Gómez-Dávila,183.

[3] Pedro Blas Gonzalez, “A South American Conservative Sage,” Modern Age: A quarterly Review, Vol. 57, No. 1. Winter (2015): 77-81.

[4] Gómez-Dávila, 25.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

________________________

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link