Aberdaron: On the Preservation of Wonderment

by Theodore Dalrymple (November 2024)

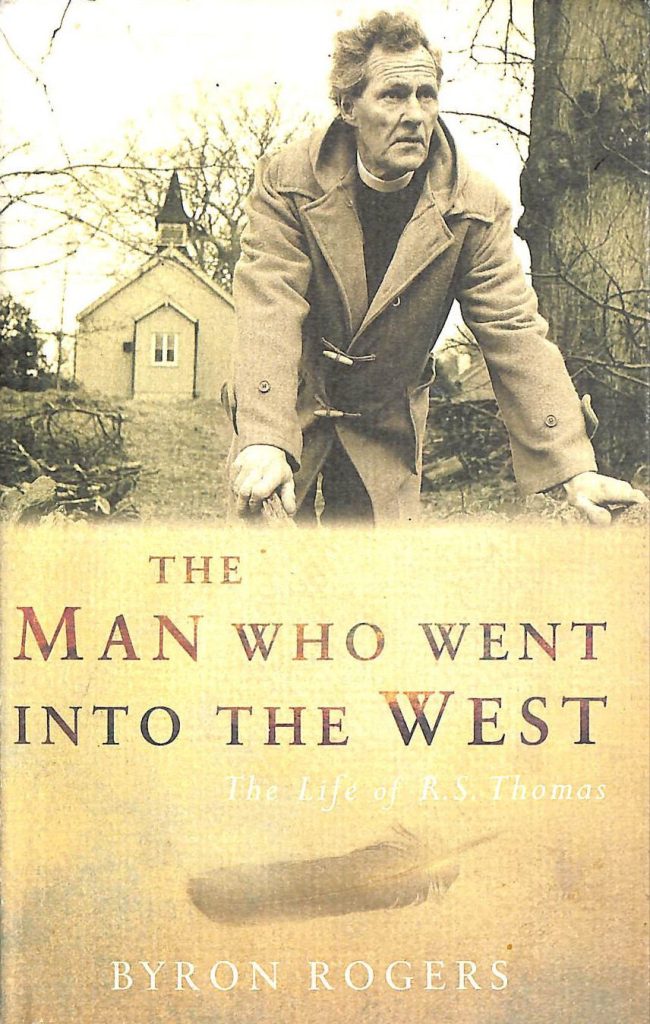

Two of the finest literary biographies known to me—not, I must confess, an immense category—are Margaret Lane’s life of Edgard Wallace, and Byron Rogers’ life of R.S. Thomas.

I suppose that some purists might not consider a biography of Edgar Wallace literary in the purest sense, though some of Wallace’s books are still in print a century after their publication (which is more than can be said for the books of the great majority of writers). This might, however, be more a testimony to the persistence of bad taste than to literary merit; but be that as it may, Margaret Lane’s book is very finely judged, sympathetic without descent to hagiography, and critical without censoriousness. It is of a length appropriate to its subject, unfailingly interesting and very well-written. No doubt the author was assisted by the fact that she was married for a time to Wallace’s son.

I suppose that some purists might not consider a biography of Edgar Wallace literary in the purest sense, though some of Wallace’s books are still in print a century after their publication (which is more than can be said for the books of the great majority of writers). This might, however, be more a testimony to the persistence of bad taste than to literary merit; but be that as it may, Margaret Lane’s book is very finely judged, sympathetic without descent to hagiography, and critical without censoriousness. It is of a length appropriate to its subject, unfailingly interesting and very well-written. No doubt the author was assisted by the fact that she was married for a time to Wallace’s son.

No one would express any reservations about the literariness of Byron Rogers’ biography of R.S. Thomas, The Man Who Went into the West, for Thomas was one of the foremost poets of his day. He was both an impossible and a perfect subject for a biography: impossible because he was so secretive and prickly, and perfect for the very same reason. Thomas was about as approachable as a porcupine, but Rogers, who met him several times, manages to pluck out, if not the heart, at least the pericardium of his mystery.

Thomas (1913 – 2000) was an Anglican clergyman who, after ordination, spent his career in various isolated rural parishes in Wales. Most of the Welsh was non-conformist protestant—Methodists and the like—so his congregations were always small. In any case, Thomas was a thorough misanthrope (though, as with many misanthropes, his misanthropy might have been disappointed love) and it is said that he sometimes hid when he saw a parishioner coming, an avoidance that the parishioners reciprocated. Perhaps his life is best summed up by the caption to a photograph of Thomas as a baby that appears in the biography: ‘His first, and possibly most successful attempt at a smile.’

Thomas’ God was not meek and mild, but angry, as was Thomas himself. A Welsh nationalist who had to learn Welsh, and who spoke in an upper-class English way (though himself of modest origin), he despised most of his countrymen for their abandonment of their ancestral culture in favour of a savourless, shallow and not very successful modern materialism—comfort and consumption having become their God. His last parish before he retired as a clergyman, surviving his retirement by twenty-two years, was Aberdaron, a little village at the end of the Llyn Peninsula, where the twelfth century stone church of St Hywyn, abuts the beach, its south wall facing the sea being windowless to protect the building against the high winds and spray. By the time of his arrival in Aberdaron, Thomas was a famous poet, insofar as poets can be famous in the modern world.

When my wife asked me where in the world I wanted to go to celebrate my seventy-fifth birthday, I chose Aberdaron, as I had for my seventieth birthday, not only because of its relative ease of access from where we lived, not only because there was a simple but good hotel there with a surprisingly good restaurant, not only because the Llyn Peninsula is of outstanding beauty, not only because of its association with R.S. Thomas, but because our first visit there, eighteen years ago, was engraved on my memory for one of the happiest moments of my life.

Perhaps it is a sign of a narrow, crabbed and childless emotional life, but that moment concerned our little dog, Ramses. He was already an old dog, with only a year left to live, but the sea air on the beach invigorated him, and he ran like a puppy ahead of us, mad with joy, turning back and waiting every hundred yards to make sure that we were still following him. These were moments of undiluted, uncomplicated and almost distilled happiness that were rare in my life (and, I assume, in other people’s lives).

And when Ramses had run the entire length of the beach, we settled to sit on a rock and eat our lunch, and subsequently to read some of Thomas’s poems, Ramses being in close attendance, seeming to listen attentively but perhaps in the hope of further tit-bits.

No doubt to ascribe joy to him would be considered by strict Cartesians an unjustified anthropomorphism, the attribution of human thoughts and emotions to creatures lacking in self-consciousness. On this question, I am Janus-faced: one the one hand I believe that there is a categorical difference, a gulf if you like, between man and the rest of animal creation, the latter quite incapable of propositional thought, but on the other ready to ascribe joy to a dog (or for that matter misery) because not to do so necessitates mental contortions to deny the evidence of one’s own eyes.

And though I liked to think of my dog as uniquely clever, expressive and loving, when I see other people on the beach with their dog, I see that they—the dogs—are as joyful there as was Ramses. Ever since, I have watched fogs gambolling on the beach with their masters and mistresses with great pleasure, though slightly tinged with envy as I no longer have a dog. It is curious how restful, how consoling, watching even unknown people playing at a distance with their dogs can be. This time at Aberdaron, we stopped to watch, my wife and I, a couple throwing a ball for their dog, a curly-haired cross between a spaniel and poodle, to fetch for them from the edge of the sea. The couple were engaged in conversation and sometimes waited too long for the dog’s convenience to throw it again. Then he would rush round them in circles, yapping a little to draw attention to himself, and asking for them to throw the ball again. How in these circumstances could anyone say that the dog was not enjoying his game, the enjoyment of the game being an end in itself, for example a reward such as dog biscuit, such as behaviourists might once have argued? What violence to the obvious would that require!

I can watch dogs playing on the beach with their masters and mistresses for an hour on end, but to do so gives rise in me to troubling thoughts about the way we raise and eat meat. Pigs, it is said, are capable of all the affection for humans that dogs evince (I am slightly sceptical of this, but let it pass for the sake of argument).

It is surely one thing to raise a pig and finally kill it oneself for food, with some kind of regret or respect, and another to raise pigs and kill pigs anonymously in factories as if they were mere transistors or microchips, outsourcing, so to speak, the suffering entailed by the mass production that is necessary if we are all to buy and eat meat. R.S. Thomas was a fierce proponent of the necessity for us to live an authentic existence close to our subsistence (though he himself was a supremely unpractical man, almost unable to change a lightbulb, and poetry is, as he himself implied in his earliest poems, far from the concerns of the subsistence farmer, or peasant), and would probably have agreed, at least in theory, to the proposition that we should not eat the flesh of creature that we were not prepared ourselves to kill.

On the other hand, one can’t really accuse Thomas of having been a sentimentalist when it came to living close to Nature, at least in its Cambrian form. Much as he denounced machine living (his wife was unusual in removing central heating rather than installing it and he would not have domestic appliances such as vacuum cleaners because they made noise), he does not make living on the Welsh hillsides sound very inviting, to say the least. And indeed, only a few minutes crossing a field on the slope of a Welsh hillside on an averagely wet day should be more than sufficient to persuade anyone of the truth of this. Even the sheep, native unto this element, as Gertrude put it, are prey to all kind of unpleasantness in the hilly Welsh countryside, as Thomas himself acknowledges, where parasites and perpetual damp and cold are their lot.

In his first book, The Stones of the Field, published by a tiny publishing outfit located above a chip shop in Carmarthen, Thomas invented a Welsh peasant called Iago Prytherch, the word peasant being a provocation in itself. In the poem, A Peasant, Thomas specifically says that he is describing not an individual, but a type or class of Welshman:

Iago Prytherch his name, though be it allowed,

Just an ordinary man of bald Welsh hills,

Who pens a few sheep in a gap of cloud.

Iago is no one’s idea of an attractive man, nor is his way of life such as would inspire anyone to emulate it:

Docking mangels, chipping the green skin

From the yellow bones with a half-witted grin

Of satisfaction…

On returning home:

… see him fixed on his chair

Motionless, except when he leans to gob in the fire.

There is something frightening in the vacancy of his mind.

His clothes, sour with years of sweat

And animal contact, shock the refined.

Horrify, perhaps, would be a better word for it. Many of us decry the supposed benefits of progress, but these lines surely give progress a good name.

But there is something authentic and elemental about Iago Prytherch, at least in Thomas’ estimation:

Yet this is your prototype, who, season by season

Against siege of rain and the wind’s attrition,

Preserves his stock, an impregnable fortress

Not to be stormed even in death’s confusion.

I have myself witnessed the heroism and even nobility of peasant life and subsistence farming in various parts of the world, but I know that I would rather die than lead such a life myself: and the history of human migration almost everywhere suggests that the loss of authenticity that Thoams laments, twinges of which I occasionally feel myself, is welcomed by the great mass of mankind, who rush to escape that life.

Thomas was more interested in birds than in his fellow-humans. They were for him a consolation for the ugliness of life, especially in its modern, suburbanised form. His poem, Swifts, is reminiscent of Wordsworth’s The Table Turned. Here is Wordsworth:

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

And here is Thomas on swifts:

The swifts winnow the air.

It is pleasant at the end of the day

To watch the. I have shut the mind

On fools. The ’phone’s frenzy

Is over…

–

…I am learning to bring

Only my wonder to the contemplation

Of the geometry of their dark wings.

To study them scientifically, according to Thomas, would be to dilute or soil our wonderment, to make what is marvellous prosaic. Keats was of like mind:

Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine—

Unweave a rainbow…

Wordsworth, Keats, Thomas: were they right? As on many questions, I face both ways. I know what they mean: we need to maintain our wonderment at Creation, and it is terrible if we lose it or never have it in the first place (a condition that social media promotes).

On the other hand, to know more about the nature of reality can merely push the wonderment one question further back. A child at a certain stage of development asks an adult Why? and, on receiving an answer, asks again Why? How many questions does it take to reach the stage of unanswerability, and therefore of wonderment? No doubt Thomas would say, then, why bother to find out why? Why not just stop at the wonderment evoked by mere observation?

I am glad that there are poets who ask this question, as I am glad that there are people who did not stop to ask it.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast