By Guido Mina di Sospiro (September 2020)

HV2, No 17b, John Cage

A slightly edited excerpt from my book Terror and Music. The context: Milan in the late 1970s, one of the looniest places and times in the recent history of the western world.

One foggy and smoggy morning I found, in front of my high school Leonardo da Vinci, a crew from the state television. It transpired that they were interviewing students about a highly anticipated and publicized concert by the American experimental composer John Cage, which he would be giving shortly in a Milanese theater.

The interviewer in front of the Leonardo—it’s all documented on a video on YouTube—asked students whether or not they knew who John Cage was, what genres of music they listened to and, if they didn’t listen to music, why not? These did not come off as interviews, but as interrogations. Apparently, music education was a must, and those who weren’t educated, or simply did not know who John Cage was, were hardly worthy of his consideration. They weren’t just philistines—they were vermin.

Then the interviewer stumbled on one of the concert’s organizers, and asked him, “Listen, why have you brought Cage into a context aimed at young people? Are you sure that this personality, a personality that belongs to ‘serious’ music—”

“John Cage,” the organizer cut him short, a young man with abundant facial hair threatening to turn into a proper beard, “is one who has destroyed the schemas of music, and since young people are those who try to destroy the old schemas of society, we find him extremely consistent with this idea. Ours is a stimulating proposition, a creative one, and in fact it will create problems, and will certainly stir up a debate on music, on what it means to make music, and also on what it means to be alive. John Cage is just the one who is useful for this kind of things.”

I was familiar with John Cage not only through the farcical impersonations of the composer Miklós Rózsa, who at that stage of my life was my mentor, but because I had listened to his music. Cage is still considered among the major composers of the twentieth century. How he had been adopted by the Italian ultra-left in the 1970s remains a bit of mystery; far from popular, at the time I could hardly think of more rarefied and inaccessible music.

The concert was attended by an audience of two thousand, mainly students. I was there, too, with my friends and classmates Marzio and Andrea.

John Cage was on stage, sitting at a table, with a lamp on it, and two microphones from a nearby tripod. He launched into Empty Words—in his intentions, “residue” of all fourteen volumes of Henry David Thoreau’s journals—by blabbering unintelligible syllabic clusters into the loudly amplified microphones. Heady stuff, no doubt, for the adoring audience.

Five, ten, fifteen minutes later, things had not changed much at all, and the audience was becoming less adoring.

Twenty minutes into the concert, some kids began to boo.

Soon enough, more noise was being produced by the audience than by the musician, who, unperturbed, kept repeating the same non-words.

Cage was fond of quoting the Zen Buddhist saying: “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.” The implicit parallel was between his compositions and the Gatha—a Sanskrit word meaning “verse” or “hymn”—used in Buddhist literature to designate the versified portion of the sutras. Gathas certainly employ repetition, as does the rosary, with its succession of fifty-three Hail Marys. Down the centuries such prayers have been repeated billions of times, enough, possibly, to form their own morphic field, as my friend Rupert Sheldrake would define it years later, or even an egregore, a group thought-form, or collective group mind. Cage ought to have known better than to compare his compositions with such spiritual powerhouses from both the East and the West. Perhaps it was wishful thinking on his side, to expect for his compositions to be played for billions of times.

That said, his use of the I Ching—the Book of Changes, the five-thousand-year-old Chinese divination/cosmological text—as his compositional tool later in his life endeared him to me. If there is one book to pick from, that would seem be the one. I had an ambivalent attitude toward experimentation: there was something about it that won me over, even if sitting through that kind of music could be as exciting as watching dust settle.

And in fact the audience was by now in revolt mode, clapping rhythmically to drown Cage out, catcalling, insulting, shouting slogans (at which they were adept). The most annoyed among them had gotten up on stage and were harassing the composer, who soldiered on.

“Comrades,” a voice from a megaphone broke through, “this is a match between us and him. If we stick together, we win. Let’s be quiet, comrades, or else he wins.”

Andrea, wearing his characteristic trench coat, climbed up on stage, walked straight up to the composer and turned off his lamp, whispering in his ear, “You’re in danger. Stop.” But Cage turned the lamp back on, and continued.

No harm came to him, and it all ended with a very liberating applause.

Had he “won the match?” And what sort of a notion was that, anyway?

I remember thinking that what those two thousands pissed-off kids needed was either their money back or, better yet, to be fed the Ramones.

Cage’s aleatory music, from the Latin alea, dice, was left to chance. Later in his life, he held the extreme belief that music should be devoid of musicians; none of that persuaded me beyond its “shock” value.

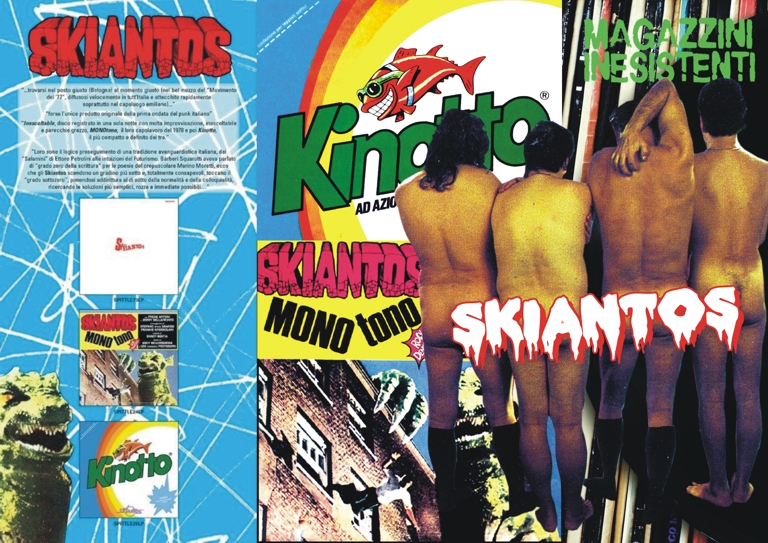

A similar but more down-to-earth provocation came during the same period from The Skiantos, a group of “demential” punk rock from Bologna. Along with their instruments, one memorable evening they brought on stage a kitchen, a table, a TV set and a refrigerator. Then they proceeded to boil spaghetti, which they eventually ate, without playing a single note. As the audience booed and protested, their leader, singer Freak Antoni, took the microphone and said: “You don’t understand a fuck. This is avant-garde, you shitty audience!”

In an interview toward the end of his life, Cage stated, “If you listen to Beethoven or to Mozart, you see that they’re always the same, but if you listen to traffic, you see that it’s always different.” As he died a year later, this could be his epitaph. Another famous, or infamous, depending on one’s taste, composition of his was 4’33”, in three movements, in which the score imparted to the musicians not to play their instruments. Gimmicks both, Cage’s and the Skiantos’, with the latter being more hands-on as it involved the boiling and then eating of spaghetti.

Heaven knows I’ve become a fan of silence—but traffic? I don’t know what kind of traffic Cage was listening to, nor can I rule out that somewhere in the world cars and trucks together are not uneuphonic. The readers will judge for themselves whether they prefer to listen to Beethoven and to Mozart, or to traffic.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link