Oscar Wilde and the Birth of Cool

by Robert Lewis (November 2022)

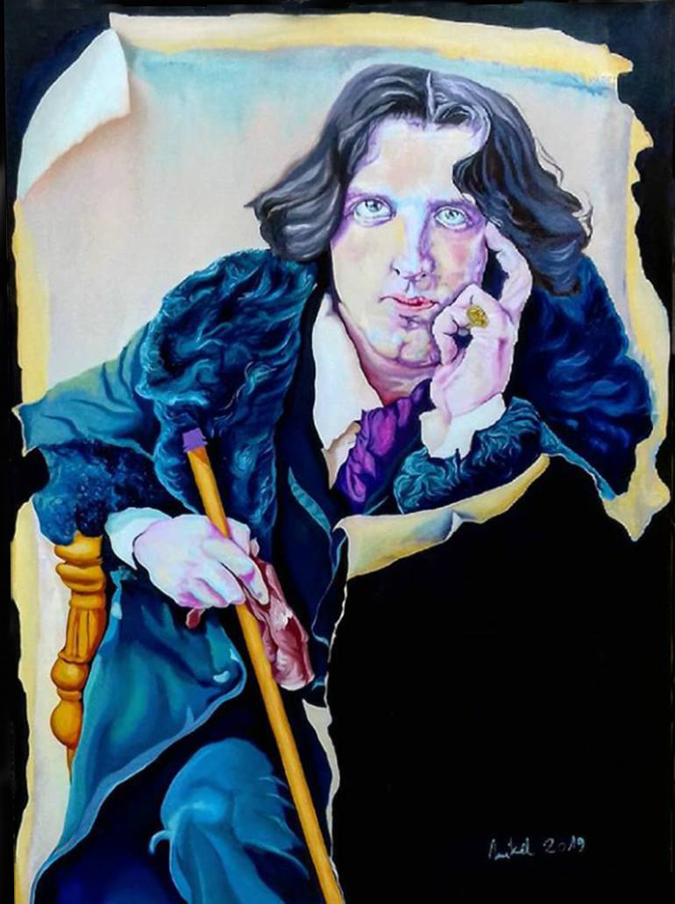

Oscar Wilde, Mikél Mato

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person.

Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth. —Oscar Wilde

Nothing gives one person so much advantage over another

as to remain always cool and unruffled

under all circumstances. —Thomas Jefferson

Camille Paglia, in Sexual Personae, makes the case that Oscar Wilde has not been given his due as one of western literature’s seminal figures, that literary criticism has failed to distinguish between the production of great literature—which Wilde did not produce—and being of great literary and historical importance. Even though Paglia did not fully grasp how the Wilde persona, as especially revealed in his stage characters, would influence the 20th century and beyond, her penetration into his sexual-psychological makeup as it affected his writing (The Importance of Being Earnest and The Picture of Dorian Gray) remains unsurpassed, and since then it has become increasingly difficult to overlook his authority.

Wilde, through his literary personae, is largely responsible for making explicit the attitude or comportment we refer to as “cool,” which significantly predates the “birth of cool,” attributed to jazz trumpeter Miles Davis in the 1950s. The archetypes of cool are Wilde’s theater characters and, from The Picture of Dorian Gray, pretty boy Dorian Gray and his mentor Lord Henry Wotton, whose other-worldly nonchalance and studied detatchment introduce the world to a state of mind (being cool) that functions like a firewall against all manner of hurt and heartbreak, injustice and prejudice.

From ancient Greek tragedy to the late Romantic period, with few exceptions, engaging theatre and literature depended on the interaction of emotionally overwrought personages with whom audiences would therapeutically empathize in order to better grasp or sublimate their own emotional upheaval. The passions were prized above everything else and the price paid (breakdown, depression) was a matter of course and audience expectation.

Enter Oscar Wilde, who dared to snub the conventional wisdom that it was one’s duty to wear the emotions on the worn-out sleeve. In Dorian Gray and his plays, Wilde’s below-zero (cool) characters are able to run life’s emotional gauntlets without suffering the usual hard knocks and injury. What sets his characters apart is they are able to rise and then remain above the fray, far from the madding crowd, which is cool’s surprisingly easily won promise. Audiences were immediately drawn to his personages for their teflonic quality and preternatural ability to maintain their equipoise in the most trying of circumstance. Attending a Wilde play was like tuning into an instructional video on how to be cool.

What at once fascinates and distinguishes the main characters (souls on ice) in The Importance of Being Earnest is their aloofness, their unflappable calm and cool in response to conflict or disappointment. Despite Wilde’s legendary wit and epigrammatic brilliance, it’s not so much what his characters have to say that argues for their importance in the history of literature, but how they say it. Hurts and insults bounce off his personages like arrows off a hard hat.

Once entered into the public domain through his plays and novel, Wilde’s manner of cool quickly became de rigueur, the garment of choice. Everyone wanted to wear it, to be seen in it. Its pharmaceutical properties created a demand that has only increased in the present age.

Since we have come to rely on especially the arts for glimpses into future cultural and social developments and transformations, it was almost inevitable that the visual arts, in the wide wake of Wilde, would dramatically break with the past and enter its version of cool into the cultural landscape.

In the early 1900s, a mere 15 years after Wilde’s passing, Picasso, Braque and Leger were systematically geometrizing the curves and flesh of the human face and body. Cubist portraiture features figures and faces drained of all emotional content while flesh and body completely disappear in the 2-D flattening out process. This trend achieved its apogee in Mondrian, whose strictly geometrical art would eventually morph into minimalism and monochromatic painting, forms that reject any content. It might have taken 500 years from the wretched figure of Christ cringing on the cross to Rothco’s “Orange and Yellow” (1956), but with the advent of minimalism (Rothko, Newman, Molinari) the emotions are totally purged from the visual arts. Cool art now commands hot prices in the volatile art market.

Art goers seeking calm and repose were richly rewarded by minimalist (content-free) art and looked for more of the same outside the gallery. They found it in the music of Miles Davis in the early 50s, and in the Hammond B-3 organ sound of Jimmy Smith. With the aim of dramatically lowering the temperature, both turned their backs on the frenzied, overwrought, angry explosiveness that characterized Bee-Bop led by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. Davis slowed everything down to a walk and revived the ballads, while the steel, skyscraper-slick, cold metal Hammond B-3 organ sound generated by Jimmy Smith hit the brain like a drug. It didn’t take long to figure out that with nothing but the clothes on your back for an asset mix, Smith’s smooth, ice-glazed notes could make you feel you were on top of the world for as long as the music lasted.

In his time, there were good reasons Wilde would be attracted to the cool, meticulously carapaced, desexed personae we meet in his plays. In the late 19th century, Wilde was a homosexual in a time when one would have liked “not to be.” For appearance’s sake, he married and fathered two children so he could more easily comply with his outlaw nature in the face of public censure and homophobia. To an uncertain extent, he was able to live life on his own terms until 1895 when he was convicted of sodomy and sentenced to two years of humiliating hard labour from which he never recovered. He died a broken man in 1900 at the age of 43.

But if Wilde was unable to escape the Bible-backed, set-in-stone moral constrictions of his time, his most famous character, Dorian Gray, from the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, discovers that he can do whatever he wants with impunity since it’s his portrait that suffers the excesses.

Wilde, through his alter-ego, is yet another example of the abused becoming (sublimated through literature) the abuser. Pretty boy Dorian, charming, irresistible to both sexes, treats his conquests with the contempt of indifference. Nothing gets under his skin. In pursuit of beauty, pleasure and power, he shrinks the parameters of empathy to absolute zero: “What people call insincerity is simply a method by which we can multiply our personalities.”

Transferring the hurt and ostracism he endured in real life to the painting, Wilde (Dorian Gray), now authors the pain while remaining deviously disengaged, as cold as the ice that runs through his veins. And if towards the end of the book Gray vacillates between being cool and stung with remorse, Lord Henry (Harry), whom the protégé worships, stays the course and quietly earns top billing as cool’s crowning achievement. In the crucible of his callousness, he transmutes every tragedy into a joke or witticism. Lord Henry is so composed we’re not sure if we’re dealing with a living person or a computer-generated avatar. Either way, whatever it is that he’s got, it registers as cool, and everyone who comes in contact with it (if only subconsciously) wants it. If we measure charisma by the number of people caught in its net, Dorian Gray and Lord Henry (the cool they underwrite) are easily among literature’s most charismatic personality types. With a half-nod to de Sade, whose coolness took on monstrous proportions, Wilde’s articulate, intelligent, gentlemanly characters make cool respectable (marketable). And be as it may that his characters are not so much flesh and blood as literary devices or projections of the author looking to remake the world in his own image, their over-the-top, immaculate style creates the necessary conditions for the birthing of cool and its subsequent influence on world culture.

Since Wilde, cool has evolved into a universal coping mechanism used to combat all manner of adversity and indignity. In the area of consumption, very few products can be successfully marketed without making major concessions to cool. Nike without the endorsement of the world’s top (cool) athletes would be a non-descript running shoe. The same with celebrity fashion.

In the 21st century, relationships, more and more of which are conducted digitally, are in particular vulnerable to the promises of cool. In McLuhan speak, and predicted by the path of least resistance principle to which humans are easy prey, it is much easier to conduct a cool (digital) relationship, than a hot (person to person) one.

Like any powerful pleasurable drug, once tried, it’s hard not to try it again. As a way of dealing with the judgmental gaze of the other, cool is the perfect retort to the often punishing and debilitating effects of self-consciousness. Cool is synonymous with reversion to animal unselfconsciousness and it shares the same end-game as drugs and alcohol, which suggests that human beings, existentially, are simply not constituted to be human day in and day out. Or, in Freudian terms, all of us entertain an unacknowledged death wish or “wish to return to the inanimate.”

More than anything and in answer to his deepest yearnings, Wilde wanted to escape the world that would eventually crush him. Since “we cannot offend nature” he writes “art is our spirited protest, our gallant attempt to teach Nature her proper place.” So while Wilde, the founding father of cool, could not save himself through his art, his late 19th century “walk on the wild side” prepared the world for the walk that would change the world. Cool not only survives him but has found a permanent home in the modern psyche.

There isn’t a person in the world who wouldn’t rather be rich and powerful, attractive and intelligent—and to those non-negotiables we now add “cool.”

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been published in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast