Patricia Craig in Kilclief

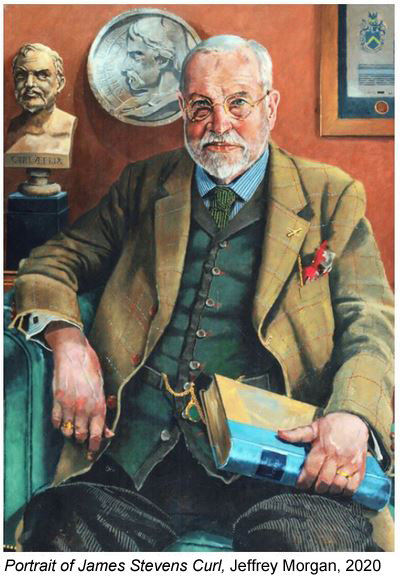

by James Stevens Curl (August 2021)

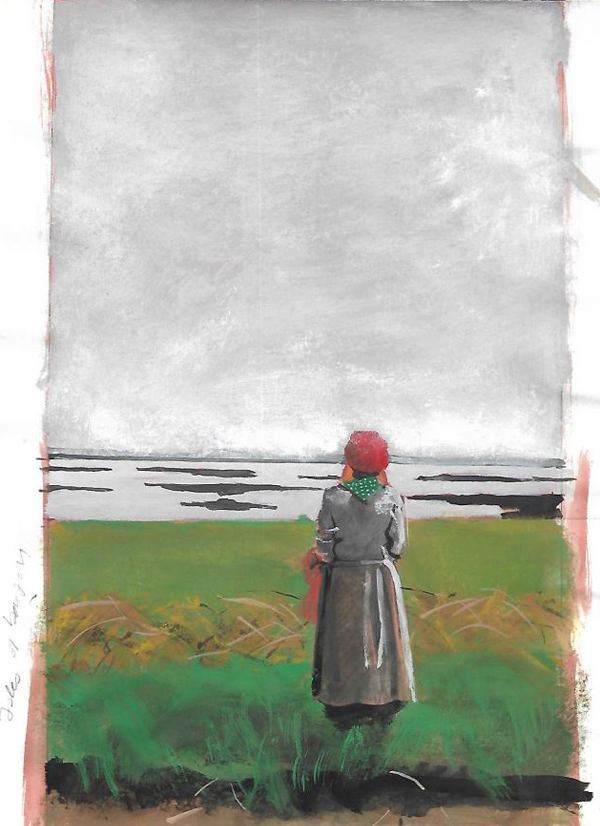

Patricia Craig Gazing Out to Sea, Jeffrey Morgan

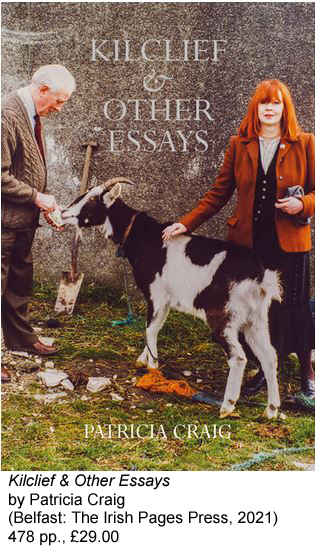

Patricia Craig (b.1943) is a distinguished Irish author, who was born and received her early education in Ulster. This rather wonderful book is a collection of her pithy essays and pungent reviews, some of which were originally published in Dublin Review of Books, Independent, Independent Magazine, Independent Weekend Review, The Irish Times, London Review of Books, New Society, New Statesman and Society, New York Review of Books, The Spectator, The Sunday Times, and Times Literary Supplement.

It begins, however, with a previously unpublished Prologue entitled ‘Kilclief,’ and as that name appears in the tome’s title, a brief explanation of what it means is given here.

Samuel Lewis, in his A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London: S. Lewis & Co., 1837), informs us that Kilclief is a parish in the Barony of Lecale,[1] County Down, in the Province of Ulster, and that it had an abbey and a castle that was ‘anciently’ the palace of the Bishops of Down. The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland (Dublin, London, & Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1846) is rather more informative, stating that Kilclief lies along the west side of the entrance, or lower part of the channel, of Strangford Lough, and that the village of the same name stands on the sea-shore, 1½ miles north by west of Killard Point, and 2 miles south of the village of Strangford. The ‘castle’, which is actually a crenellated tower-house, is called in Irish Caisleán Cill Cléithe (the second two words, Anglicised as ‘Kilclief’, meaning ‘Church of the Wattles’, or ‘Wattle Church’, cliath signifying a wattle or a hurdle), and was built in the first half of the fifteenth century. It was within its walls that John Cely (or Sely), Bishop of Down, ‘lived in open and infamous sin with a married woman’ called Lettice Whailey Savage, and appears to have plotted various ‘treasons, transgressions, and other crimes, for which he was indicted, outlawed, and [not without difficulty] unmitred and unfrocked’ by Pope Eugene IV (r.1431-47) in 1442, after which the See was united with Connor, and became the Diocese of Down and Connor. Craig speculates that perhaps ‘Kilclief’ may have derived from the Irish Cill Claimhe, meaning ‘Church of the Lepers’: as the Parliamentary Gazetteer states, ‘old writers say … that an hospital was founded here for lepers’. That source, however, rather pooh-poohs the notion, ‘alleged by monastic dreamers, that there was at one time an abbey of regular canons, founded by St Patrick, and presided over by two of his disciples, who were brothers, and named Eugenius and Neill’. Lettice Savage, it seems, apart from the charms with which she seems to have entertained the Bishop, collected rare ceramics, but what precisely was meant by that will probably never be known.

Samuel Lewis, in his A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London: S. Lewis & Co., 1837), informs us that Kilclief is a parish in the Barony of Lecale,[1] County Down, in the Province of Ulster, and that it had an abbey and a castle that was ‘anciently’ the palace of the Bishops of Down. The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland (Dublin, London, & Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1846) is rather more informative, stating that Kilclief lies along the west side of the entrance, or lower part of the channel, of Strangford Lough, and that the village of the same name stands on the sea-shore, 1½ miles north by west of Killard Point, and 2 miles south of the village of Strangford. The ‘castle’, which is actually a crenellated tower-house, is called in Irish Caisleán Cill Cléithe (the second two words, Anglicised as ‘Kilclief’, meaning ‘Church of the Wattles’, or ‘Wattle Church’, cliath signifying a wattle or a hurdle), and was built in the first half of the fifteenth century. It was within its walls that John Cely (or Sely), Bishop of Down, ‘lived in open and infamous sin with a married woman’ called Lettice Whailey Savage, and appears to have plotted various ‘treasons, transgressions, and other crimes, for which he was indicted, outlawed, and [not without difficulty] unmitred and unfrocked’ by Pope Eugene IV (r.1431-47) in 1442, after which the See was united with Connor, and became the Diocese of Down and Connor. Craig speculates that perhaps ‘Kilclief’ may have derived from the Irish Cill Claimhe, meaning ‘Church of the Lepers’: as the Parliamentary Gazetteer states, ‘old writers say … that an hospital was founded here for lepers’. That source, however, rather pooh-poohs the notion, ‘alleged by monastic dreamers, that there was at one time an abbey of regular canons, founded by St Patrick, and presided over by two of his disciples, who were brothers, and named Eugenius and Neill’. Lettice Savage, it seems, apart from the charms with which she seems to have entertained the Bishop, collected rare ceramics, but what precisely was meant by that will probably never be known.

Craig had moved to London from Belfast in the mid-1960s to study at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. As that decade neared its end, Belfast’s ‘old, untroubled, dull, decorous atmosphere’ had become ‘a thing of the past’, and the place was ‘on a course towards disaster’. By 1976 her parents ‘had had enough of fear and loathing’, and had come to ‘crave tranquillity. They were sick of the sight of boarded-up shops, bomb damage, a burning bus against the backdrop of Divis Mountain’, and ended up in Kilclief, a place they had never heard of ‘before chance deposited them along the rocky shore of Strangford Lough, looking across to the southern end of the Ards Peninsula’. By that time Craig was living with ‘two enchanting cats’ and her husband, the artist Jeffrey Morgan (b.1942), in south-east London, at Blackheath, to be precise, and was to remain there until 1999, when they uprooted and settled in Antrim. From the early 1980s Craig and Morgan would spend a part of every Summer at Kilclief, growing to ‘relish its pure clear air, its ever-changing sea—one minute azure, the next stone-grey—its birds and butterflies and profuse vegetation, its gorse and montbretia[2] along the roadside, … the beach before the house, the rocks commandeered by lolling seals’. While there, they immersed themselves in the history and beauty of the place, often sharing those with friends who came down to spend time with them: these included the poets Derek Mahon (1941-2020), Paul Muldoon (b. 1951), and Michael Longley (b.1939), with whom they explored places like Isle O’Valla, a ruin that was ‘beautiful, spooky, and utterly unreclaimable’, yet had all sorts of historical and literary connections which Craig mellifluously describes and celebrates.

Clearly, Craig has drawn much inspiration from the area, from ‘the landscapes and inscapes of this part of coastal and inland Lecale … Over the topographical features—back roads, the back gate of Castle Ward, beech trees along the River Quoile—is superimposed a vibrant sense of history and melancholy; the pungency … of history, especially local history with its obscure tragedies, its dead struck by lightning, drowned, murdered, lost in some forgotten battle or other. And always, the sombre coast as a haunt of seals’. There, she wrote much, and gradually the place established ‘a tentative and easily dissolvable hold’ on her. That is what Ireland does to you: it takes you over, dissolves you, immerses you in its mysterious, drenched sadness, and changes you for ever. At Kilclief, the rocks, the shore, the ‘castle’, the seals, the ‘whins aflame around Easter’, ‘the exorbitant weather’, somehow coalesce ‘beyond the commonplace, … beyond gainsaying.’

Clearly, Craig has drawn much inspiration from the area, from ‘the landscapes and inscapes of this part of coastal and inland Lecale … Over the topographical features—back roads, the back gate of Castle Ward, beech trees along the River Quoile—is superimposed a vibrant sense of history and melancholy; the pungency … of history, especially local history with its obscure tragedies, its dead struck by lightning, drowned, murdered, lost in some forgotten battle or other. And always, the sombre coast as a haunt of seals’. There, she wrote much, and gradually the place established ‘a tentative and easily dissolvable hold’ on her. That is what Ireland does to you: it takes you over, dissolves you, immerses you in its mysterious, drenched sadness, and changes you for ever. At Kilclief, the rocks, the shore, the ‘castle’, the seals, the ‘whins aflame around Easter’, ‘the exorbitant weather’, somehow coalesce ‘beyond the commonplace, … beyond gainsaying.’

This marvellous book, starting with the Kilclief Prologue, is divided into sections entitled ‘Red Hands and Dancing Feet’, ‘Pious Girls and Swearing Fathers’, and ‘Fiddlesticks!’: each section has short reviews and essays, including some material on MI5 and the murky world of spies, agents, and traitors. I knew some of the strange characters mentioned, and they were certainly a rum lot. As the pieces are quite short, the book is ideal bed-time reading: agreeable, beautifully written, and diverting, it is delightful, food for thought, and far-removed from ghastly Wokeism and other contemporary horrors. It is a huge pity it does not have an Index, though, as that would have made it much more user-friendly, and a few of Jeffrey Morgan’s lovely paintings would have lifted the whole into æsthetic realms rarely found in these benighted times.

[1] An Anglicised version of Leath Cathail, meaning ‘Cathal’s Half’ or ‘Share’ of the country.

[2] Crocosmia, an invasive, non-native flowering plant, of the iridaceæ family.

James Stevens Curl was awarded The President’s Medal of the British Academy in 2017 for ‘outstanding service to the cause of the humanities’ in recognition of his ‘contribution to the wider study of the History of Architecture in Britain and Ireland’. He is a Member of the Royal Irish Academy, and is the author of many scholarly books and papers.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast