Peculiar Architecture: Book Review

by James Stevens Curl (August 2022)

Architecture’s New Strangeness: A 21st Century Cult of Peculiarity, by Kenneth M. Moffett

Novato, CA: Gordon Goff ORO Editions, 2022, softback, 114 pp., many b&w. illus., £14.00

We live in terrible times of shifting sands, when truth is lies, beauty is a dirty word, and fractured ugliness is pronounced a paradigm by the Commissars of criticism within a Politburo that brooks no dissent. Moffett, a practising architect, has concluded that ‘building design in the first decades of the 21st century accepts and pursues some increasingly odd and disturbing trends, and … there seems to be insufficient architectural criticism that calls these trends to account … Remarkable advances in the power of computer programming, permitting the simulation, manipulation and documentation of complex and continuously varying surfaces and volumes, are surely one factor, opening the door to design opportunities that are unprecedented and have thus not stood the test of time. Another powerful factor would be the combination of wealth polarization and the growing influence in the modern world of authoritarian regimes. The latter have the power to unilaterally call for huge projects of untested design … Also the proliferation of the ultra-rich in the modern world—oligarchs, sheiks, emperors of tech—has likewise facilitated the [making] of often bizarre architecture that serves ego far more than the marketplace.’

Quite so, but then Modernism was always the tool of authoritarians who care nothing for ordinary human beings, the craftsmen, the toilers, and serve nobody but themselves and their often disreputable paymasters.

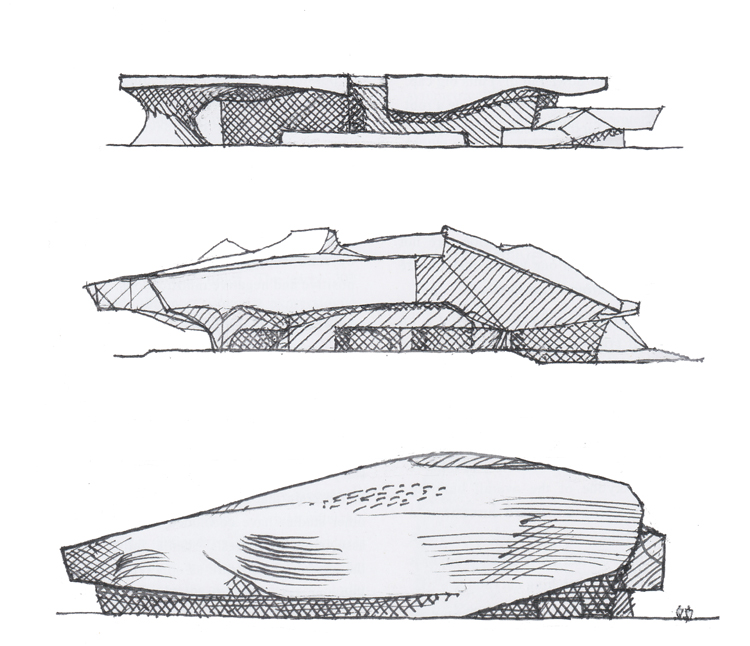

In this timely book, Moffett illustrates with his own drawings the inhumane, grotesque bizarreries recently inflicted on an unfortunate world by architects who have betrayed the Vitruvian ideals of Commodity, Firmness, and Delight in favour of Packaging, Deformation, Instability, and Uglification. Take the Musée des Confluences, sited on a peninsula between the Rivers Rhône and Saône at Lyon, France (designed by Coop Himmelb[l]au from 2000, opened 2014, much over budget, of course, another requisite of the starchitect): a restless essay in sliced swoops of metal and glass, it was created with the stated aim to express turbulence and change. Have we not got enough tumult and violence in this battered, overpopulated world as it is, without this ‘lumbering cyborg dinosaur’ (as the Architectural Review, ccxxxvii/1423 [September 2015] 9, amazingly called it, in a welcome breaking of ranks), a ‘fatuous, pretentious, exorbitant wrapper,’ with ‘all the lightness of a lump of lead,’ outrageous in its ‘wasteful, harmful, … overweening excess.’ The architect’s job used to be to create Order out of Chaos: nowadays, the task seems to be the opposite, grasped eagerly by the celebrities of Grub Street. And what is the purpose of a museum? In this one, the impact of the structure and spaces on the visitor takes precedence over the mere exhibits, which, like the history to which those artefacts are connected, no longer count in a fractured world, when culture is a dirty word, and nihilism is rampant.

A calmer atmosphere might serve the exhibits in a museum rather better than does frenzied visual tumult achieved at huge expense, part, perhaps, of the fashionable quest for sensationalism and ‘immediate impact,’ but, given the gestation period, the inchoate heap already looks tired and hopelessly out-of-date. Moffett calls it ‘an assembly of crimped and cut flat surfaces of shiny cladding and glass that call up the image of a crocodile having emerged from the river to chomp its way towards downtown.’

And that’s being kind.

Moffett ‘is inclined to agree’ with the analysis in my Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, 2019) that a certain amount of vitriol is warranted when considering the unholy mess that is architecture today. He rightly condemns unbridled capitalism, education (primarily a lack thereof), and Hubris for working together to ‘bring us a lot of bad buildings,’ but he correctly fingers the co-option of Modernism by capitalism and the endless ‘isms’ that schools of architecture, tame journalists, critics, and practioners ‘came up with as the 20th century marched forth into the 21st. It is difficult, when considering the psychotic process that passes for ‘architecture’ today, not to form the opinion that the courses architecture and town planning have taken almost universally since 1945 have been deranged. Panaceas have proved not to be anything of the sort, yet, despite early evidence of failure, they were still applied, often with renewed, even frenetic, fanaticism. The ‘scientific,’ supposedly ‘rational’ bases of modernism in architecture were neither.

Inclusion of the works of many designers in books about what is supposed to be great architecture is mistaken. Challenges to the Modernism which has created an inhumane dystopia are sneered at and denounced by those who just want more of the same, because they have vested interests in continuing the ruinous policies that have virtually destroyed all vestiges of civilised living. Worship of ‘starchitects,’ whose ghastly excrescences are illustrated by Moffett, is idolatry, with everything that that idolatry brings as Nemesis: contemporary heroes of architecture are simply self-interested servants of big business, vast corporations, or repressive régimes abroad.

It is possible that our times will be viewed with astonishment in the future because of our inability to exercise intelligent critical judgement concerning what passes as ‘architecture’ (much of which is irrelevant in relation to pressing contemporary problems), but which is only empty show, ignoring context, gobbling up money, and possessing no meaning other than as an assertion of overweening self-importance. Conspicuous Deconstructivism or its misshapen offspring, so clearly delineated in Moffett’s book, are no substitutes for real architecture, and belong in the realms of vulgar extravagance, passing fashion, showing off, and superfluous bling, which the rich élites, international corporations, and authoritarian dictatorships feel entitled to inflict on everybody else. What we have, in fact, in these increasinly unequal times, is an anti-democratic ethos imposing monuments to its own self-importance on the world.

Professor Salingaros and others have connected the phenomenal success of architectural Modernism in taking over professional institutes and universities to its cult-like status. It became obvious to me that certain Modernist set texts (Holy Writ to Believers), such as those of that absurd, egotistical, fascist-sympathising, deified monster, ‘Le Corbusier’ (I call his cult ‘Corbusianity’), and the twisted arguments of Nikolaus Pevsner (pretending that the Arts-and-Crafts people were ‘pioneers’ of Modernism—the antithesis of Arts-and-Crafts ideals—because he peered at everything through Bauhaus-tinted, Gropius-worshipping spectacles), were just plain nonsense, and it amazed me that they were uncritically accepted and forced down the throats of students who were bullied into accepting them whole, otherwise they would not emerge from the sausage-machine laughably called ‘architectural education.’ Indeed, I noticed disturbing similarities between the sloganising of Modernism and the dubious ‘certainties’ of religious fundamentalism: the tone is similar, as is the self-righteousness; the shouted slogans; the simplistic attitudes; the ignoring of the past; the deliberate distortions of history; and the claims for itself as the only true way. Like all cults, Modernism is just that, but it is a very dangerous, destructive, totalitarian, illiberal phenomenon, founded, not on history, thought, or sound foundations, but on the sands of prejudice, stupidity, dogmatic assertion, and downright lies. Careful recent research has also suggested that there is much in modern architecture that is actually harmful to human beings: its threatening nature and distorted geometries do people no good at all. Harmony, unity, gravitational control, and perceived stability are crucial to any successful architecture: all are disrupted in the exemplars Moffett gives us in his book.

Modernism in architecture is responsible for untold misery, appalling ugliness, and worldwide destruction. It is used by powerful interests to impose the will to destruction of that which is humane in architecture and town planning. It is repulsive, alien, cruel, and beyond redemption. Its theorists and apologists pump out breathtakingly ignorant guff dressed up in bogus intellectual pretensions, all resembling comething as ludicrous and chimærical as the mating-calls of an air-conditioner. The public should wake up, reject mass callisthenics, and refuse to believe what it is told by architectural bullies whose failures are legion. And the texts churned out in support of Modernist architecture should be seen for what they are: distorted, lying travesties of real history, written with a leaden grasp of prose usually found in booklets of instruction for washing-machines, incompetently translated from Korean or Chinese.

Moffett illustrates the disaster well, and his heart is in the right place, but he could have been far more effective with a bit more courage of conviction, rapier wit, and a killer-instinct capable of torpedoing the outrageous pretensions of those who create Hell on earth. His book, moreover, was printed in China: one wishes that were not the case, as there are plenty of excellent printers in Europe and America perfectly capable of doing good work as reasonable prices. Giving work to countries with deplorable records in terms of freedom of expression, basic rights, and humane attitudes is as questionable as the antics of starchitects chasing the moneybags of dictators of ‘people’s republics,’ oligarchs, and gangsters.

Like it or not, the architecture of insolence has profound effects on its users, and eventually has pitiless moral consequences for those who produce it.

Professor James Stevens Curl has drawn attention in his work to some of the ‘grand narratives’ of Modernism by over-estimated authors falsely claiming that designers who loathed the whole ethos of the so-called Modern Movement were ‘pioneers’ of that disaster.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast