by Nikos Akritas (November 2023)

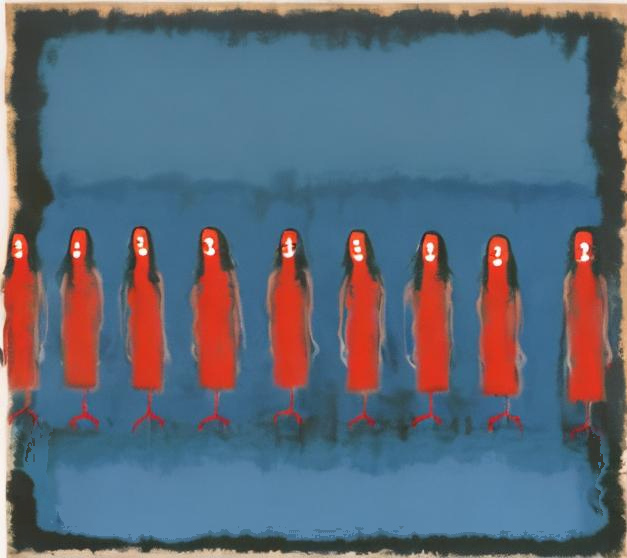

Meeting the Goal, 2023

According to the International Baccalaureate’s (IB) website, there are over 5,600 IB schools worldwide, currently educating almost two million students.[1] Conceptualised and developed in the 1960s, the IB introduced its Primary Years Programme (PYP) in 1997; its key educational influencers being John Dewey, Alexander Sullivan Neill, Jean Piaget, and Jerome Bruner.

The first of these thinkers is well known for his progressive views on society and education; the second set up the controversial A S Neill school, with a number of teachers linked to communist and socialist organisations; and the third has had an influence on education, well beyond justification, through his grossly inadequate ‘research’ and ungeneralizable findings. All were proponents of a child-centred, inquiry-based-learning approach to education, proposing theories which were just that—theories (lacking robust empirical evidence) which form the ‘philosophical’ core of the PYP.

The PYP claims to be child-centred but only subscribes to this so far, as it has essential ideas about what ‘issues’ should form part of every child’s education and what kind of people those children should be ‘moulded’ into. It claims not to be a curriculum in the proper sense of the word, with academic goals to teach towards, but it does have goals nevertheless. Given these are not academic, what might they be? Simply put, these goals aim to produce a certain kind of person who views the world in a certain way, in order to take ‘action’ and change it. It indoctrinates students with a woke mind-set and makes no pretence otherwise. We are talking about the education of three to twelve year-olds.

As one PYP trainer recently stated, echoing the IB’s mission statement on its website, “Our goal is to create a better and more peaceful world.” Not to teach children to read and write, do maths, science or anything about objectivity but to see a world that must be changed and changed in a particular way.

In their defence, PYP pundits claim they are not advocating what to teach but how to teach. But their thinking is extremely muddled. True, they advocate a mode of learning ‘through inquiry’ and assert any curriculum can be taught through their approach to learning. They claim to be championing a method, the curricula outcomes can be left to others. But they then set about demanding students display certain attributes (personality traits). These number ten in total. Children are to be:

Inquirers, Knowledgeable, Thinkers, Communicators, Principled, Open-minded, Caring, Balanced, Reflective and Risk-takers

Nothing wrong with these, surely? Except that they are explicitly aimed at producing a certain type of person. They seem innocuous enough, until one considers their expression in the form of affirmations. For example: We learn with enthusiasm or We express ourselves confidently and creatively in more than one language and in many ways. What if I’m naturally introverted and shy? Am I going to be judged if I don’t behave in these ways? Even if not, I will be fully aware that I am not fulfilling these affirmations.

Consider the following:

We act with integrity and honesty, with a strong sense of fairness and justice, and with respect for the dignity and rights of people everywhere; We engage with issues and ideas that have local and global significance; We exercise initiative in making reasoned, ethical decisions; We critically appreciate our own cultures and personal histories, as well as the values and traditions of others; We act to make a positive difference in the lives of others and in the world around us; We understand the importance of balancing different aspects of our lives to achieve well-being for ourselves and others; We thoughtfully consider the world and our own ideas and experience.

Should children as young as three really be reflecting on issues of global significance and acting to make a positive difference in the world? Pondering ethics, critically appreciating cultures and attempting to achieve well-being for others? Or is time better spent on learning devoid of social engineering? We can do it all, many in PYP schools claim. But no we can’t. There are only so many hours in the school day and children’s time at school is finite. Given the constraints of time, what are the priorities and how are they achieved most efficiently? And what of parents’ views of these affirmations?

Lessons and units of work must be planned and ‘delivered’ with the above attributes in mind. Instead of being skills and traits which are a by-product of the learning, they become equally, if not more, important. Children are encouraged to think of themselves in relation to these attributes and it becomes a cult-like obsession to ensure children are familiar, indeed fluent, with the language of the program.

This is not just a question of knowledge being downgraded relative to character traits. The time taken up with this psychobabble impacts on teaching time and so less knowledge is imparted. A good thing, PYP fundamentalists assert, as knowledge should be ‘discovered’ through ‘inquiry’ not imparted or passed on. And so, there is much re-invention of the wheel in addition to less time. Remember, these are children of elementary school age.

The fundamental assertion the PYP is a method, not a curriculum, is rather disingenuous. In addition to character traits that must be developed, there are transdisciplinary themes or units of inquiry that are a staple of a PYP pupil’s education. These units of inquiry number six and are repeated each year with slightly different emphases or central ideas. They are:

Sharing the Planet, How the World Works, Where We Are in Place and Time, How We Express Ourselves, Who We Are and How We Organize Ourselves.

The IB website describes units of inquiry as in-depth exploration[s] of … important, transcending idea[s] and concept(s). An important part of these units of learning is to get students to take action in relation to what they have learned. This does not lend itself to a mind-set of impartiality or objective analysis in later years. It is indoctrination of a particular interpretation of the world and the demand that pupils become social and/or environmental activists.

To again quote the particular trainer previously mentioned, “We are transforming, changing a culture.” This is being done through the conduit of young children. It recalls a certain saying, attributed to the Jesuits, “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man.” Dubiously, PYP ‘educators’ have children for far longer than the age of seven.

Legislators have recognized the power of advertisers to influence parents’ behaviour by targeting their children (responding accordingly) and so, true to form for any business or cult objective, have PYP fundamentalists who are “Changing mind-sets not just of kids but of parents.” Today the child. Tomorrow the world.

The whole convoluted vocabulary not only indoctrinates but muddles and befuddles any genuine academic learning through lost time, misdirection, obfuscation and emphasis on psychological and emotional factors rather than academic knowledge. What I constantly see are young children overindulged in feelings of a personal nature, next to no resilience and poor social skills. The self-esteem disease, which has now been part of Western education for a couple of generations, is not only mainstream but, allied to the PYP in IB schools, takes things one step further to dismantling the importance of learning anything beyond the personal, if it is not mandated by the IB gurus.

There is a stark contradiction in claims of method and programs of study here—for how inquiry based is a knowledge of the world in which the conclusions have already been decided and form part of a young person’s education indoctrination? Destructive ideas about education and learning have now progressed to being a curriculum which claims not to be so by its worldwide organisation. Teaching revolves around environmentalist and politically correct themes that take precedence over the curriculum they claim to support.

The claim that IB schools outperform non-IB schools is, at best, misleading. In a report commissioned by the IB themselves (raising questions over compromised impartiality) it was admitted, in the nitty gritty details, that inferences from the results of … [the] study should be made with caution as the research was conducted with limited background information about schools and students and schools participating in each country were not a random sample. The results of this study were, then, only applicable to the sample of schools who participated.[2]

Such research, with limited information on the subjects under scrutiny (schools and students), does not necessarily compare like for like, or does not, at least, attempt to limit potentially impacting variables. For this reason, and the admitted issue around sampling, the findings are not representative and therefore not generalizable, as many IB educators are misled to believe.

There is a further methodological flaw, when comparing two different programs of test results. The IB schools’ test results are those from International Schools Assessment (ISA) testing but are compared to Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test results. Although the research paper points out ISA scales are based on those for PISA, in order to compare the results directly one would have to establish a one to one correlation of test scores. I.e. can these tests and their results be used interchangeably? Are they like for like?

After lauding IB test results as above the PISA mean, a caveat is added: The results are not surprising because PISA results were based on performance of representative samples from all types of schools from each participating country. So the PISA results are representative but not the IB ones. Then why compare them?

Misconceptions around research ‘findings’ and misleading theories spread by proponents of a child centred approach to learning are nothing new. Back in 1967 David Asubel wrote:

“… examination of the research literature allegedly supportive of learning by discovery reveals that valid evidence of this nature is virtually non-existent. It appears that the various enthusiasts of the discovery method have been supporting each other research-wise … by citing each other’s opinions and assertions as evidence and by generalizing wildly from equivocal and even negative findings”[3]

Sinisterly, not only has child-centred learning continued to influence educational practice, the IB’s Primary Years Programme merges it with moulding young children into activists.

______________

[1] https://www.ibo.org/about-the-ib/facts-and-figures/#:~:text=The%20IB%20offers%20four%20educational,to%2019%20across%20the%20globe.

[2] https://www.ibo.org/globalassets/new-structure/research/pdfs/isa-final-report.pdf

[3] Ausubel, David (1968), Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston

Table of Contents

Nikos Akritas has worked as a teacher in Britain, the Middle East and Central Asia.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link