Perception, Perfection and Aesthetics

by Kenneth Francis (February 2023)

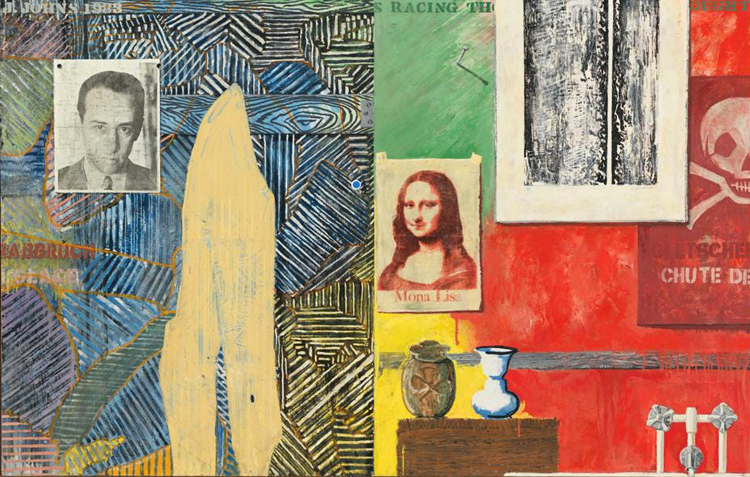

Racing Thoughts, Jasper Johns, 1983

In terms of perception, perfection, or aesthetics, how does one define something beautiful, ugly or skillful? Take, for example, the greatest soccer player of all time and what he is based on: Speed? Goalscoring record? Dribbling footwork skills or gifted defending tactics? When the Brazilian footballer, Pele, died last December, the media and sports pundits unanimously hailed him as ‘The Greatest.’

I agree he was the best forward player in terms of his graceful style, skills and contribution to ‘The Beautiful Game.’ Watching Pele play soccer was like attending a night at the opera, whereas other football greats’ goalscoring and pitch skills is like watching soft porn without the naked flesh and groans of pleasure.

But there were other players who were more skilful than Pele when it came to different field tactics. Consider these examples: The England football great Bobby Moore, who led his team to the 1966 World Cup victory, was a better defending player than Pele. According to Pele: “Bobby Moore—he defended like a lord. Let me tell you about this man. When I played, I would face up to a defender, I would beat him with my eyes, send him the wrong way … But not Bobby, not ever. He would watch the ball, he would ignore my eyes and my movement and then, when he was ready and his balance was right, he would take the ball, always hard, always fair. He was a gentleman and an incredible footballer. (Lee Clayton, Daily Mail, May 27, 2006)

To draw a movie analogy: Pele was The Godfather, while a player like Rinaldo in his prime was Goodfellas. In other words, there was something gracefully understated in Pele’s football style, as opposed to Rinaldo’s slick pitch skills.

Pele’s understated style can be found outside of football, as well as many other sports. Take for example movie actors. Sometimes method actors’ performances can be over the top and bordering on parody, whereas actors who underplay a role subtly, yield more of a sound and memorable performance.

A good example of this are the two psychopaths in the movies Blue Velvet and The French Connection. In Blue Velvet, Denis Hopper plays the part of Frank Booth, a mad man with no morals who greets his lover, played by Isabella Rossellini, by punching her and screaming obscenities at her. In fact, Frank does a lot of screaming, crying and gasping throughout the movie. All that’s missing from his face is “I AM A PSYCHO!” tattooed on his forehead, as he inhales gas from a canister.

Compare this to the performance of the psychopath Alain Charnier (played by Fernando Rey) in The French Connection. Charnier, who has hitmen murder his enemies, is a suave, reserved, classy-looking, middle-aged ‘gentleman’ who likes fine food and expensive wine.

And despite being followed by New York detectives, this man of few words gets away in the end without any moaning, screaming or inhaling gas. Paradoxically, the imperfect ending was perfectly aesthetically pleasing, as it avoided cinema morality tale conventions.

In singing, the late Whitney Huston’s powerfully thunderous voice can seem like a noisy racket when she ‘murders’ such songs as “IIIIIIIEEEIIIIIEEEIII WILL ALWAYS LOVE YOUUUUUUUUUUUU!” compared to Peggy Lee’s breezy, laid-back style in classics such as “Fever.”

Overkill endeavours are also linked to efficiency. A good example of this perfection/efficiency verses aesthetics, was given by Hubert Dreyfus during the 1980s BBC TV series The Great Philosophers, hosted by the late Bryan Magee.

In the programme featuring Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, Dreyfus said: “We don’t even seek truth anymore but simply efficiency. For us, everything is to be made as flexible as possible so as to be used as efficiently as possible.”

He said a good example of this was a Styrofoam cup: it keeps hot things hot and cold things cold and you can dispose of it when you are done with it. It’s efficient and it flexibly satisfies our desires.

He added: “It’s utterly different from, say, a Japanese teacup, which is delicate, traditional, and socialises people. It doesn’t keep the tea hot for long, and probably doesn’t satisfy anybody’s desires but that’s not important.”

But back to football. During Pele’s golden era, from the 1950s to 1970, soccer stadiums were mostly city-based (in walking distance), made of bricks and wood, with seats that could splinter your backside. The toilets stunk, almost everyone smoked, but the tickets were inexpensive; with litter everywhere and zero health and safety warnings and measures.

Contrast this to today’s pragmatically located, concrete and steel latticework, half-a-billion-pound stadiums, which resemble a giant, kidney-shaped bedpan from the air, with no smoking, everyone seated, and health and safety signs and voice-over notices everywhere, not to mention televised advertising flashing every few seconds. These soulless, wide monstrosities are no match for the stadia of yesteryear, despite the stink and lack of comfort.

All of the above reminds me of one of my favourite lines in Patrick Kavanagh’s poem, “Advent”: Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder.

Writing in the Guardian (Dec 16, 2013), Carol Rumens said: “Underlying the emotional charge of the poem is Kavanagh’s sense of his native village in Inniskeen [Ireland] as an Eden, he sacrificed for the corrupt metropolis, Dublin. His outcry is not, I think, against knowledge, but city-slick, poetically useless knowingness. If such knowledge belongs originally to ‘Doom,’ as the speaker says, it must be perceived as truly terrible, and perhaps represent the worst that could happen to this poet: the loss of local roots leading to the decay of imagination.”

Indeed, the decay of imagination is always threatened by Brave New World ways of ‘perfecting’ everything around us. Give me a ‘night at the opera’ in an old music hall anytime instead of a day in a city-slick, 20-screen, mega cinema complex screening Avatar 2. And give me Pele’s ‘Beautiful Game’ in a splintered-arsed stadium on a wet afternoon instead of a 21st century field of robots in a giant bedpan running faster than racehorses.

Table of Contents

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast