Plato, The Republic, and Democracy

by Petr Chylek (April 2024)

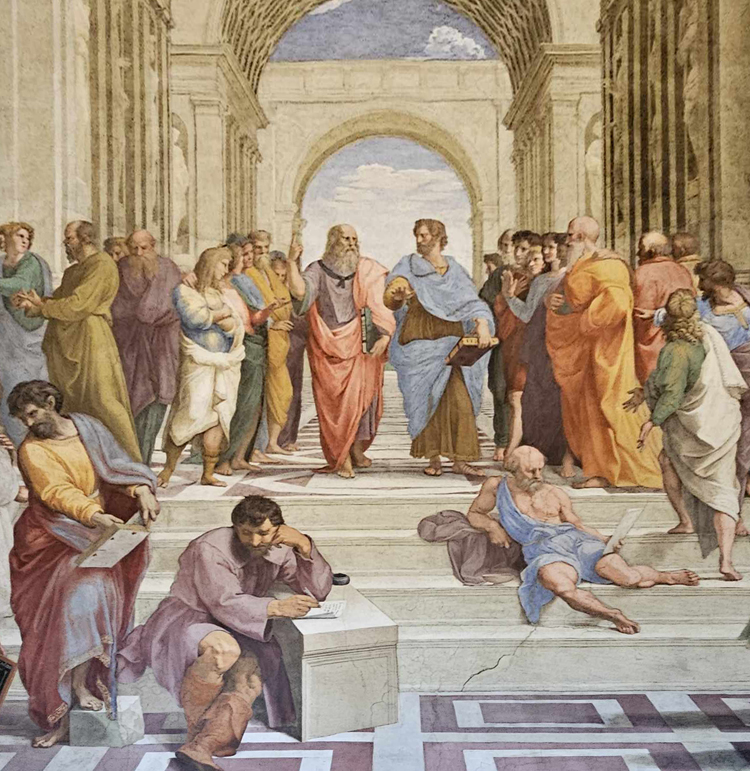

Up to the present day, democracy as a form of government has gathered about 400 years of experience. The first 200 years were in Ancient Greece, and another over 200 years have occurred in recent times. While the current political elite in the Western states tend to proclaim that democracy is the only just system of government that the whole world should adopt, the Greek philosophers considered democracy as one of the worst forms of government.

In Chapter 8 of The Republic [1], written about 400 BC, Plato (428-348 BC) considers five forms of government. I find three elements of his discussion surprising:

- Of the five considered forms of government, democracy is rated as the next to the worst.

- In his description, democracy naturally evolves into the worst regime, namely tyranny.

- In Plato’s description of details of what the ruler will do in the process of transition to tyranny, we can find several familiar steps.

The democracy in Athens that Plato describes in The Republic was direct. In a direct democracy, all important decisions are made by a vote of eligible citizens. In Athens, only educated men after their military service were given the right to vote. The voting was oriented towards governmental actions, while most governmental positions were filled by lottery.

In contrast, the current so-called liberal democracy gives voting rights to all citizens, regardless of their level of education, experience, or awareness of the political reality of the country they live in. This provides an opportunity for rich people in the USA to affect elections through a flood of TV and other forms of advertising to induce people to vote for a particular candidate. With few exceptions, voting is directed toward the election of a ruler (president in the USA) and a group of representatives who will then establish the laws and policies of the country.

Ancient Greece was a conglomerate of individual city-states. Democracy was practiced in many city-states; however, the best-preserved information we have is about the government of Athens. Socrates (470-399 BC), who was sentenced to death by the Athenian government, never wrote anything himself. However, his famous follower, Plato is believed to have described Socrates’ ideas accurately in The Republic.

The reasons for his death sentence are usually given as a lack of piety towards the Greek gods, and his corruption of the youth through his teaching.

From a more specific philosophical and religious point of view, there were two points Socrates was accused of:

- Socrates denied the anthropomorphism of gods. According to his belief, gods did not look or act like a man. This was interpreted as a lack of piety towards the gods that leads to the corruption of the minds of youth.

- Socrates believed that he could hear an inner voice that advised him, especially, about what not to do.

The Athenian court found Socrates guilty. We are told that of the 500 members of the court, 275 voted for the guilty verdict.

Death sentences were more common in ancient Athens than today in democratic countries. After Athenians lost the war against Sparta (another Greek city-state), six of its eight generals were executed. On another occasion nine of the city’s ten editors were executed (accused of stealing money) before a clerical error was found. After that, a person who accused auditors of stealing funds was executed. Thus the death sentence for Socrates was not an isolated event.

For some reason, his execution was delayed for a few days after Socrates’ conviction. During that time his friends, students, and family were allowed to visit him. It was suggested to him that he should escape. He refused. He justified that if he was a citizen of this city, and if the city sentenced him to death, he had to die. Socrates died by drinking a cup of hemlock.

According to Socrates, the immortal soul comprises three parts: a thinking rational part, an emotional part, and a part dominated by physical desires. This is quite similar to the three parts of the Soul introduced in the Torah and later in Kabbalah: Neshama, Ruach, and Nefesh in Hebrew.

Socrates classifies the rulers, citizens, and political regimes into five groups. He also assigned to each political regime a part of the soul that dominates its rulers and political elite. He arranges the governments in the city in descending order:

- King-philosopher—a theoretical ideal social organization

- Timocracy—the ruler and people value most reputation and fame

- Oligarchy—the ruler and people value most money and property

- Democracy—the ruler and people value most freedom

- Tyranny—the ruler tries to keep his power and dominance through any means necessary

The first type of social order and governance is considered to be the only just social order. However, from this ideal state, the chain of development inexorably leads to the four lower unjust social systems.

The King-philosopher is supposed to be aware of the highest part of his soul, called the rational soul by Plato. This part of the soul dominates his thoughts, speech, and actions. The king has been properly educated in arts and sciences and received appropriate training in government and politics. His prime interest is acquiring wisdom and translating it into practical knowledge. He has the lower parts of his soul, responsible for emotions and desires, under control. Despite that, he makes some mistakes, like appointing people to positions of responsibility for which they are not properly educated and which are not in harmony with their natural abilities. Due to his mistakes, the ideal social system will decay, and the next social system, called timocracy, arises.

In timocracy, the citizens and their leaders are interested predominantly in recognition, reputation, and fame, rather than in wisdom and knowledge. Their soul awareness is somewhere in between the highest rational and the middle emotional soul levels. Some people start valuing money and property more than their reputation and fame. Thus, we come to a social system called oligarchy.

In an oligarchy, the most valued goals for the ruler and citizens are money and property. This leads to some people becoming rich and others poor. The poor hates the rich and the rich are afraid of the poor. A city under oligarchy produces as a byproduct beggars, thieves, pickpockets, and robbers. The dominating part of the soul is somewhere in between the emotional part and the part dominated by desires for physical pleasures. When the rich become too rich and the poor too poor, a democracy arrives, either through violence or by the resignation of the rich and powerful due to fear of violence.

As stated by Plato:

Then democracy comes into being when the poor win …. by arms or by others withdrawing due to fear. [557a]*

Then democracy seems a sweet regime … dispensing a certain equality to equal and unequal alike. [558c]

In democracy, according to Plato, the most valued feature is freedom. However, people will start misusing their demand for freedom. Soon they will demand unrestricted freedom. The soul will be dominated by its lowest part, by desires for physical pleasures. Some of the people will demand that they can do whatever they want. They will not realize that your unrestricted freedom represents unreasonable restrictions for your neighbor. Crimes will increase and people will demand law and order, and democracy will be replaced by tyranny.

The path from democracy to tyranny in modern times was envisioned by James Madison (1751-1836), one of the Founding Fathers and the fourth president of the United States, who wrote [2]:

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.

According to Plato, the three lowest states of government, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny, will evolve from one to another and sometimes coexist simultaneously. Plato states that in this state:

- All people are treated equally in their abilities, equal and unequal alike [558c]

- Insolence is called a good education [560e]

- Students have no respect for teachers [563a]

- Teachers are afraid of the students [563a]

- People have no self-discipline [560d]

- Some people are pursuing their physical desires excessively [558d]

- People are accustomed to setting up one man as their special leader and making him grow great; a tyrant grows naturally from the root of leadership [565d]

- The tyrant will present himself as the champion of the poor against the rich

- He will take away the substance of those who have it and distribute it to the people [565a]

- Those men whose property is taken away are compelled to defend themselves by speaking before the people. For this, they are charged by the others. The people do them injustice, not willingly but out of ignorance because they are deceived by the slanderers [565b]

- He will cancel the debts of the poor and redistribute the land [566a]

- He will accuse people falsely and bring them before the court [565e]

- If he suspects a man of having free thoughts and not putting up with his rule, he will find a pretext for destroying him [567a]

- He will start many wars since in a war people need a leader [566e]

A similarity with past historical developments, and with the current state of the world cannot be missed. The current liberal democracy is considered by many as the final state of human society; i.e., the end of history. We are just waiting for the whole world to accept our Western-style governmental system voluntarily, or by force.

However, the Old Testament, the Torah says:

When you make for me an altar of stones, do not build it from hewn stones … (Exodus 20:22)

Don’t try to make all the stones of the same shape and size. Each country has its own history and its own culture. Each situation is different. Insisting on the same form of government for all will not work. Have respect for other stones’ sizes, shapes, colors, and whispers.

___________

[1] A. Bloom, The Republic of Plato. Basic Books, New York 1991

[2] The Federalist Papers, No. 47, 1788, Library of Congress, http://thomas.loc.gov/home/histdox/fedpapers.html

*Parentheses with three numerals and a letter designate the section of The Republic according to its 16th-century edition.

Table of Contents

Petr Chylek is a theoretical physicist. He was a professor of physics and atmospheric science at several US and Canadian universities. He is an author of over 150 publications in scientific journals. He thanks James D. Klett and Lily A. Chylek for reading the earlier version of this article and for their comments and suggestions.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast