Poison Ivy

By Myron Gananian (December 2023)

The Ivy League Schools—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Columbia, Brown, Penn, and Dartmouth—comprise a very small number of universities in the United States out of a total of 3,200. It is commendable (yet at the same time worrisome) that, for a very long time, they have provided an outsized number of those who have led and populated the halls of our State Department. For many years, that proportion has been about 25% but recently about 20%.

It is not only their intellectual achievements but their social status that commends them for a career that historically is regarded as the doorway to a diplomatic career. What differentiates our State Department, however, is that this university-based, dynastic, legacy history has not been duplicated in any other nation’s history to the same degree (though it has been duplicated to a lesser extent in Great Britain). From time immemorial, Foreign Ministers, known as Secretaries of State in the US, have risen to their high status primarily on the basis of merit. To name just a few, Tallyrand, Potemkin, Richelieu, Benjamin Franklin, and Bismarck (though titled Chancellor), and, of course, Henry Kissinger. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s father and paternal uncle were both US Ambassadors. All three of them attended Harvard while Anthony Blinken went on to Law School at Columbia. Does noting this influence raise other concerns, as it should?

Has our foreign policy, which displayed a clear demarcation from its previous tenets at the very end of the 19th century, been influenced, if not controlled, by the personal and world outlook of the institutions which spawned the graduates who profoundly determined the way the US deals not only with friend but especially foe?

It is proper to speculate whether the ethos of these universities has bled over into our foreign relations? At present, this ethos, criticized as “Male, Pale, and Yale” is being countered by the current popular effort at diversifying the State’s workforce. Is the lack of diversity the State Department’s most serious problem or is there something of “The Ivy Imprint” which has engendered some of the most costly American misadventures while leading to the current vacillatory and sometimes feckless fumbling, and confused posture that appears to have caused us to react to external affairs rather than to being anticipatory and leading? The US seems to be eternally not just out of step with the rest of the world, but constantly in conflict—a role that does not comport with the role of the world’s most influential nation.

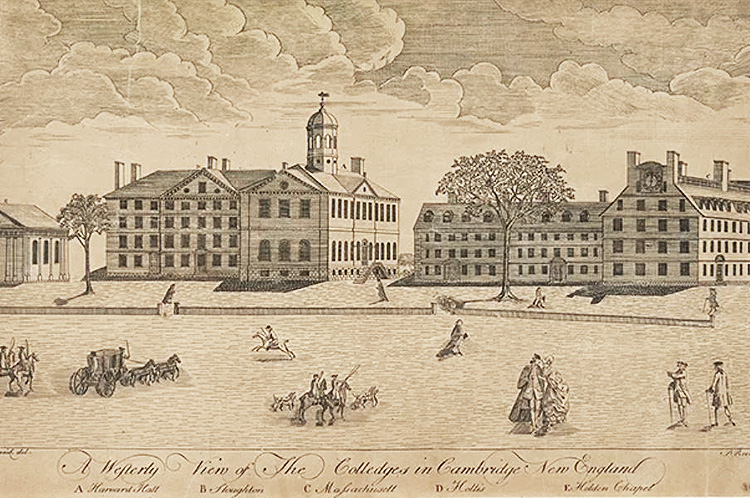

Is there something in America’s birthright, of which Harvard, Princeton, and Yale were essential and indelible contributors that, for the first century of our nation’s existence, led to an unduplicated record almost totally free from errors and condemnation—save from those defeated in conquest (their contribution to this admirable record is not to be denied)? But, then—to be followed by the 20th and 21st centuries which included disaster after disaster in Central and South America and major military involvement almost without cease and with no achievement of the inciting goals (excepting our two World War involvements)?

Is it possible that “In God We Trust,” applied in its purest form, saved us from mishap in the 19th Century to then became, “If Not Our God, Then Godless”? An underrecognized consequence of our Judeo-Christian heritage is the unhappy proclivity of Monotheism to imbue its adherents with a mantle of superiority and condemnation for those who do not believe so. This attitude, applied more in the political realm and not in the religious sense, though the latter the parent of the former, came to the fore at the end of the 19th Century when the US grew out of its juvenile period, and becoming powerful, was able to spread its influence and control as far afield as Guam and the Philippines, as well as Cuba. Manifest Destiny run amok and the Monroe Doctrine, a pillar of America’s early foreign policy, denied to all others. This attitude of physical and political strength unavoidably led to a sense that non-Americans were of lesser physical, moral, and political capability, and lacked the purity of soul that guided us from Day One. From there it was a short, quick step to becoming Lord of The Universe and then as Bret Stephens famously said, “To say that America needs to be the world’s policeman, is not to say we need to be its priest.” Nowhere in our society is this priestliness better entrenched and expressed than in the ancient, hallowed universities of the staid Northeastern United States. In sum, the US feels that unless other nations duplicate our unique form of democracy almost to the letter that they are not capable or deserving of determining the destiny of the land between their borders (note the repeated efforts at regime change, almost exclusively an American policy). This policy intends not to conquer but to duplicate our form of democracy in as many foreign capitals as possible. Conquest is far more realistic since that is just what happened to Japan and Germany as a result of WWII. Complete annihilation, which allowed the creation of democracies closer to our heart in contrast with the results almost everywhere else, as in Iran, Congo, Iraq, and on and on. This endless list of failures is a consequence of seeing ourselves as such enviable examples of perfect democracy that other nations would be gravely mistaken to not want to emulate us. Where is the nation to which we can point with pride and say, “There, we birthed a nation in our image.”

Our initial foreign relations posture was strongly determined by the sentiments so beautifully expressed in George Washington’s Farewell Address, providing a stark contrast to the arrogance and bellicosity of our more recent overseas embarrassments. Washington’s words were a constitution applied to foreign dealings. We will rue the day it was disregarded. Unfortunately, any effort to obey his principals is now regarded as Isolationism, a sobriquet equivalent to racism.

We must not overlook the importance of religion in the founding and foundations of these universities. For example, Princeton’s motto in Latin is “Under God’s Power She Flourishes.” Harvard’s is “Truth for Christ and The Church.” While Yale’s motto is more obscure, its meaning is similar. Using Hebrew words, meaning “Light and Truth,” it is a reference to the Hebrew priests using light and truth to discern the will of God. Perversely, this purity of faith became a weapon for asserting dominance. Not entirely different than a Crusade couched in benevolence.

If we are to regard the cause of this long decline in our ability to deal with the rest of the world from a more elevated philosophical position rather just attributing missteps to personalities and institutions, we might conclude that the US manages its foreign dealings on the basis of an ideology and in that sense is not so different from a theocracy, such as Iran.

If it is agreed that “Geography is Destiny,” it could follow that those favored universities share the social and religious outlook of their neighborhood, New England. There is, after all, a field of study called “Geographic Psychology.” Of the many characteristics that stand out are a strong conviction that their status as the first region in the US to be settled defines them as pioneers, and being the “Firstest” bolsters their sense of superiority and likely the most malignant attitude, that of not needing to change. This inflexibility, this rigidity, does not serve the US well since today’s world is not like yesterday’s.

This intransigence would not have created as much worldly turmoil were it not for the haughty, superior, and condemnatory posture embodied in New England’s history and psyche. The combination of condemnation for any and all who do not emulate our standard of democracy cannot but guarantee friction, for the world is not constituted as our blessed history and endowments permitted. Even the path of several admired Democracies is disgusting in their sanguineous nascence. The road to British and French Democracy is strewn with severed heads, leaving little to be admired. What a contrast are our Revolution and universally respected Founding Fathers. We have so much to be admired when compared to the rest of the world. For shame that we did not sustain that special sense and apply it with the self-respect and humility that it deserves.

While the US has much of which to be proud it would serve us well to be mindful of Proverbs 16:18: Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.

Table of Contents

Myron Gananian is a retired physician living in California.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast