Property and Power

A Documentary Proposal

by Geoffrey Clarfield (November 2022)

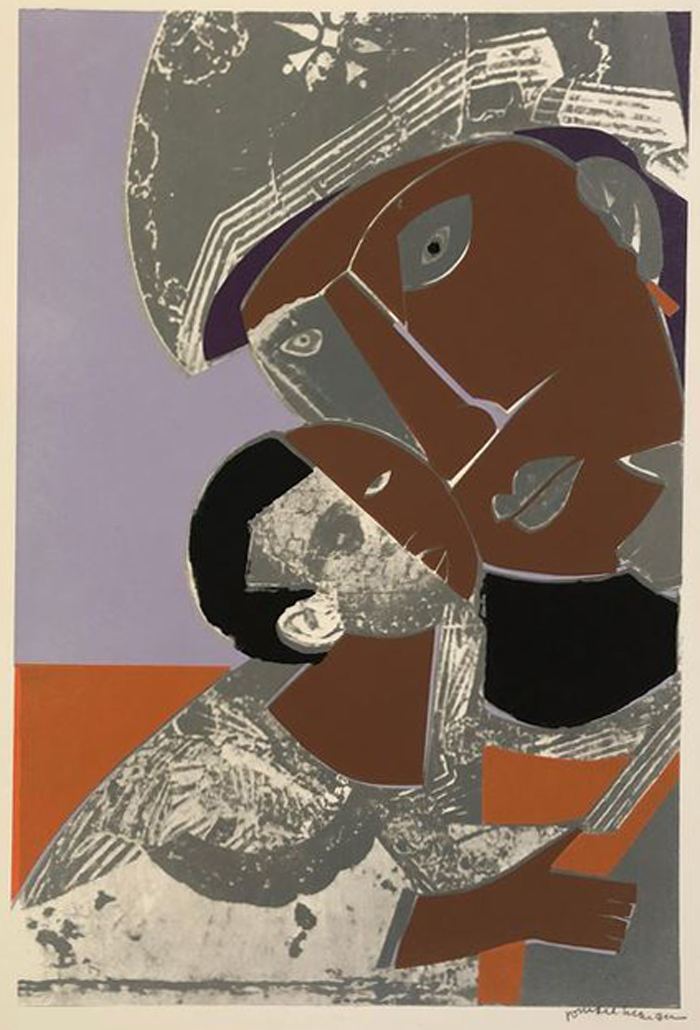

Mother and Child, Romare Bearden, 1972

I studied anthropology at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. I became so enamored of the field and its sub discipline ethnomusicology, that I managed to get a grant and get sent to the deserts of Northern Kenya for two years, to record and learn to understand the music of a camel herding tribe called the Rendille.

Instead of returning to the West I stayed on in sub–Saharan Africa for another 15 years, first as a researcher in rural development, then as a development project manager. I kept up with the anthropological literature about Africa and some of the developments in the social sciences. And so theoretical anthropology became my avocation as opposed to my vocation. Because I was no longer fighting the academic battles of a discipline that was hurtling leftwards, I could write about Africa from perspectives that would have difficulty finding a home in academia.

Along the way I started reading more about cultural ecology and macrosociology, which I had explored in graduate school but had put aside in order to throw myself into a field research paradigm that used ethnolinguistic methods to extend the ethnographic particularism of the great founders and exponents of American Cultural anthropology, men like Franz Boas and students of his such as Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. I was not disappointed and following in their footsteps allowed me to discover much about how the Rendille see the world.

But macrosociology is quite different, and it helps us see the tribal world from the outside in, not the inside out. And so, as I established a home and office in the regional East African city of Nairobi, I began to see Kenya in terms of cultural ecology and macrosociology. I imagined it visually and wrote this treatment for a documentary film that I believe still deserves to be made. Read on if you are still interested.

Introduction

African studies as an academic discipline are less than a century old. Before the second half of the 20th century, little was known about the history, ethnography and ecology of African societies. Today there are now vast libraries of material in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese outlining the lifeways and history of Africa’s diverse people. We now talk about Africa’s thousands of tribal peoples, its more than forty independent states, its exploding capital cities and the worldwide competition to access its rich natural resources.

When I first set foot in East Africa in 1985, I saw diversity all around me. It took many years working among different African people and diving into the literature to begin to see the forest from the trees. This is what I discovered.

A Time When All Were Equal

Twelve thousand years ago, all of our ancestors lived in hunter gatherer societies. Men tracked wild game and women gathered wild fruits. There was little specialization. People were spaced widely across the land and there is archaeological evidence to show that life was relatively peaceful and non-violent. Some anthropologists have even argued that hunter gatherer life was the original `affluent society’.

Mass Societies and the Will to Power

The world is now dominated by mass societies who base their complicated technologies on the extraction of nonrenewable resources from the earth, petrol products and a variety of metals and minerals. Unlike hunter gatherers these social systems are hierarchical and specialized. They are politically characterized by the search for ever increasing power and wealth by their political elites who are interested in international domination, whether they be Chinese, Japanese, European or American.

The Paradox of Property

Hunter gatherer society was and, in many places, still is, characterized by an absence of private property or very lose definitions of it. Modern society is defined by the fact that people own their own labor which they can then sell on the open market. At best, they can maintain some amount of private property that is legally theirs to dispose of across the generations.

Such a paradox raises a host of questions.

How did we come from there to here in such a short time?

How much of the ancient hunter gatherer way of life survives today?

What has changed?

What force is driving this change?

Are there societies in remote parts of the world who have avoided this transformation?

If so, where are they?

Does there way of life contain lessons to show us where we went wrong, and can they help us explain why we have become the way we are?

Is it our fault or is it a response to overpopulation and intersocietal competition?

Can the way some traditional societies have survived into the twentieth century help explain how it is that we have come to look upon the earth’s resources as just another form of property to be sold or disposed of on the open market?

And finally, are some of these people organized so that they do not let the individual run riot with the disposal of his or her property when it is not in the common interest?

A Land Where Time Stood Still

Despite the fact that Kenya is host to a little less than a million Western tourists each year who come to view the game in its parks. Today few people realize that this country also contains living examples of cultures in every stage of human evolution since the dawn of humankind.

Hunter gatherers inhabit the last remaining indigenous forests of East Africa. Neolithic fishermen such as the El Molo live on the shores of Lake Turkana. Pastoral tribes like the Masai live in iron age conditions on the savannahs. Slash and burn horticulturalists live near the coastal forests close by their sacred groves, while not far away Swahili Muslim traders maintain a medieval lifestyle on the Indian Ocean coast and adjacent islands. In the midst of all this, in Victorian splendor live remnants of aristocratic European farmers and ranchers, descendants of colonial settlers. The cities are home to a full-fledged industrial and computerized modern economy of offices, factories and suburbs with private schools and many, many slums.

A Propertied Hypothesis

Each one of these societies has its distinct relation to property and power. This film would examine four of them: hunter/gatherers, pastoralists, horticulturalists and suburbanites. And it will show just how it is that as society gets larger, property gets smaller.

The Evidence

The four societies to be highlighted in this film could be described briefly in the following ways.

Hunter Gatherers-Dorrobo Groups; People Without Cattle

Hunter Gatherers-Dorrobo Groups; People Without Cattle

A few thousand years ago Kenya was home to a large variety of hunter gatherer groups. There is evidence that they may have resembled the San or Bushmen who are now confined to the Kalahari Desert of southern Africa. The rock art that they have left behind and their archaeological remains all suggest that there existed a number of loosely related groups of people who had adjusted their lifestyle to differing environments.

With the coming of pastoral peoples from the north such as the Masai and the Rendille, Bantu horticulturalists from the west and Arab settlers along the coast these bands of families began to fragment and retreat into those areas that were not coveted by the incoming peoples. In most cases these were remote forests, usually in hard-to-reach mountain ranges and isolated river basins. What makes all these groups similar to each other and different from the surrounding pastoralists and horticulturists, is that until recently they did not raise domestic animals in any significant way.

Over the centuries they have developed a variety of symbiotic relationships with the tribes that have `encapsulated’ them. They have adopted their language and much of their costume and ceremonial life. But there are a number of economic and cultural features that distinguish them from their more powerful hosts and that show that these groups were once one unique.

Prominent among these are a phenomenal ability and love for the hunting of wild game, a detailed knowledge of local plants and their medicinal capacities, a preference for the eating of wild animals, the cultivation of honey hives and groups of allied families without hereditary leaders. They also often provide essential ritual services for the larger tribes.

The hunter gatherer peoples who today still live among the Masai (the Dorrobo, which means people without cattle) circumcise all Masai warriors during their initiation. Among the Masai as in the mythology of many other incoming groups, these hunter/gatherers are thought to have given the land to the newcomers in a pact of friendship when they first arrived in Kenya. In short it is universally accepted that they are the `first people’.

Hunter gatherer land tenure ranges from the relative freehold among the Boni forest dwellers, to a mixed system among the Nkebotok to a more familiar system (to us) of family territories and primogeniture among the Dorrobo of the Ndoto Mountains and the Okiek (Dorrobo) of the Mau Forest.

Horticulturalists—The Mijikenda of the Indian Ocean Coastal Forest and Plains

The elders of the nine tribes that comprise the Mijikenda confederation tell of a time long ago when they migrated to Kenya from their far away homeland-`Shungwaya’. This tale and its variants are similar to many others that describe the movement of slash and burn Bantu horticulturalists, who with their iron hoes and west African food plants brought a form of food production that allowed for greater surpluses and concentrations of populations than either pastoralists or hunter/gatherers could maintain.

The Mijikenda developed a more hierarchical form of clan and territorially based social organization than the pastoralists and hunter/gatherers with chiefs, complicated dance mask rituals and a land tenure system which encouraged sons to expand the perimeters of the settlement with their own households. The ecological heart and the sacred center of these societies were the hallowed, sacred groves called `Kayas’. Until recently these acted as the political and ritual center of Mijikenda life, while at the same time preserving the numerous wild and domestic plants that supported their subsistence pattern.

The Mijikenda are famous for their palm wine and gracious lifestyle and until recently they still judged all disputes over land or power through powerful and respected councils of elders who would periodically meet in these `Kayas’.

The Rendille-Camel Nomads of Kenya’s Northern Frontier

The Rendille are a group of Cushitic speaking camel herders who wander the arid lands of the Kaisut desert, southeast of Lake Turkana. They speak an archaic form of the Somali language but of the four and half million Muslim Somalis living in the Horn of Africa today the less than one hundred thousand souls who comprise the Rendille have never converted to Islam.

Despite this they have a well-developed monotheistic religion and believe in a God who is invisible and omnipresent. The more than sixty thousand square kilometers of the Rendille homeland is owned by no individual, family, lineage or clan. Any Rendille elder or warrior can take his animals or settlement anywhere within this territory. Wells are `owned’ by the lineages whose ancestors dug them.

In practice this amounts only to the right to a first watering of animals if the owners and other Rendille arrive at the well at the same time. Although some herds of domestic animals are owned outright, others are borrowed in whole or in part by a wide variety of kin and friends who crosscut family, lineage and clan boundaries and who bind a variety of Rendille elders into complicated networks of what are called technically labelled by anthropologists as `bond friendships.

These friendships give a host of rights and obligation to those who partake of them. For example, some `loaned ‘animals have been known to be tracked for generations until the whole system is so confused so that people give up.

The protection of the tribal homeland is the responsibility of the warrior grades which include all men from the ages of approximately sixteen to thirty-two. These warriors live in the satellite camps and are jointly responsible for the protection of the clan and the care of its domestic animals. They are accompanied by young girls. Together with them and away from almost all supervision by the elders, they live a life that is a combination of the Boy Scouts and Hell’s Angels.

Nairobi and the Rush to the Suburbs

Nairobi is the capital of Kenya and the regional financial and administrative capital of East Africa. It provides a host of goods and services for Uganda, Tanzania, the Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia. The United Nations has one of its programs permanently based in Nairobi. In addition to being the home of the Kenyan economic and political elite, it is a place where expatriates from many countries live and work for years at a time.

The administrative framework of Nairobi was established by the British. Outside of municipally held properties all land is held and sold by private owners according to legal statutes set down by the British and adopted by independent Kenya. The life of the city revolves around commerce and government and in many ways is indistinguishable from that of any other western city. All modernizing Kenyans aspire to a house in the suburbs, membership in a private golf club and the extra cash to go to some of the first-rate restaurants and hotels scattered about the city.

The downside of this is that the ostentatious lifestyle of the upwardly mobile Kenyans is a magnet for landless peasants who come from the rural areas looking for wage labor and hoping that one day, they too can join the Karen Club and wear their three-piece suit. Unfortunately, the demographics of the modern Kenyan economy ensure that the shanty town is about as far as most of them get. In the end Nairobi is divided into three classes: the super-rich, the upwardly mobile and slum dwellers.

And so if you travel freely throughout Kenya today you will make a 12,000 year journey through time, starting with hunters and gatherers, moving on to the horticulturalists who came to Kenya from West Africa with the rise of slash and burn agriculture, (Horticulture), and the specialized pastoralists who came from the Sudan and Somalia and finally with the medieval like Islamic traders of the Swahili coast, all of who were conquered by the British and who established a settler class in the early 20th century that gave way to a tribal elite who adopted the religion and life style of their former masters.

It is a remarkable tale, and, in this documentary, we would follow an individual from each of these “social types” to give the viewer a visually evocative story of human evolution and development. No one has done this yet. Any offers?

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast