By Norman Berdichevsky (July 2018)

Here Comes the Wind, Benny Andrews, 1980

The mainstream media continually defend what they believe to be “the rights” of illegal immigrants in order to make amends for allegations (all false) of “racism”. It is noteworthy to look how these two issues are linked in their raw, unvarnished, unadulterated, form in the Dominican Republic to appreciate the enormous contrasts between what has been achieved in the United States and the sad fate of a country which lacks the protection of our constitution, an independent supreme court, and just laws. In such a country, the government officials and army hold many of the same deep prejudices of a large part of the population and which become playthings to be manipulated.

In a relatively short amount of time, Dominican citizenship was on paper at first a constitutional right granted to

- all those born in the country (according to the constitution that prevailed until 2010); it then was changed overnight so that this right was subsequently limited to:

- those born in the country to parents who were Dominican citizens at the time of their children’s birth, superseding the previous law and then changed again in 2013 so that

- it included a provision reminiscent of the “grandfather clause” used to deny African-Americans their right to vote in many Southern states for more than two generations following the civil war. This last new constitutional change is “Ex post facto”. It grants citizenship only to those who individuals were born on Dominican territory after 1929 to parents who, at the time of their child’s birth were “legitimate and resident Dominican citizens” and could prove this by documentation. The Central Electoral Board was charged to carry out a detailed audit of all births recorded in the Civil Registry from June 21, 1929 forward to April 18, 2007 (date of the adoption of the original constitution). This was done to identify all “foreigners” (those who could not prove citizenship by documentation) and are thereby “deemed improperly registered”. They are then added to a “List of Foreigners Improperly Listed in the Civil Registry of the Dominican Republic.” This is known by the euphemism of “regularlization”.

These provisions were aimed exclusively at Haitians and those of dark skinned Haitian origin who are almost all instantly recognizable as of “African origin” and therefore suspected of illegal entry form that neighboring country into the Dominican Republic.

In practice this has meant that the individual of Haitian descent can be deported by the “authorities” (often border guards acting without any legal restraint) on sight. The immediate effects of these changes were that 200,000 formerly Dominican citizen of Haitian origin were immediately made stateless and given one year to put their names on the new official registry. Over 55,000 were deported by the time of this deadline and 120,000 “voluntarily” fled to Haiti.

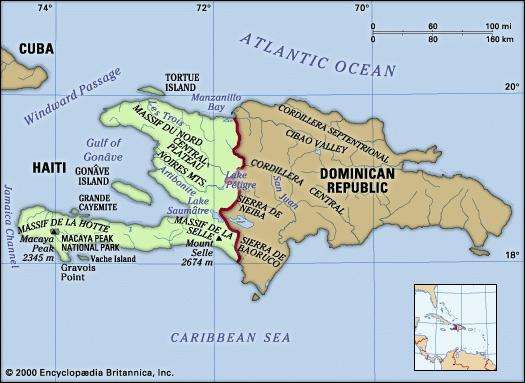

Haiti and the Dominican Republic share the island of Hispaniola and a long and hostile relationship which is exacerbated by differences in race, culture, language and a history of genocidal attacks, the worst occurring in 1937 during the regime of dictator Rafael Trujillo, and for the most part largely ignored by the world press. Just as the two thousand year old tragedy of Jewish homelessness culminated in the Holocaust and the creation of a specific term for anti-Jewish racism, antisemitism, the Dominican authorities and people have long been accustomed to speaking of antihaitianismo, no matter how many subterfuges are used to hide it from the rest of the “Hispanic” or “Latino” world.

Like antisemitism, antihatianismo is the selective interpretation of historical facts, and the creation of a Dominican national consciousness that identifies nationality with skin color, language and what many or most “Latinos” believe is a Hispanic character, variously and often emotionally described as “Hispanidad” or “La Raza”. Lacking all three of these, no Haitian can, in reality, ever fully identify with the Dominican Republic, just as many European peoples mistrusted Jews as a “foreign body.”

According to the prevailing Identity Politics dominating the Democrat Party for more than a generation, “Latinos” and “African-Americans” are both “Peoples of Color” and thus natural allies as “minorities” within the United States. The George Zimmerman—Trayvon Martin case in February 2012 illustrate the flaws in the concept as the dominant media outlets screamed about a racial crime implicating Zimmerman as the guilty party as a “white” individual who had struck out against an attacker and then used his firearm against a “defenseless” unarmed African-American whom then President Obama spoke of in sympathetic terms because Martin “could have been my own son” based purely on “race” or skin color yet the media quickly dropped the whole case when bias used by major networks in reporting what George Zimmerman had actually said during his cell phone call became known.

Zimmerman’s own complexion was not much lighter than Obama’s and his family was, on his father’s side, of Hispanic origin. A jury unanimously found that Zimmerman had acted in self-defense after suffering pounding of his head onto the pavement by Martin who had attacked him.

The Dominican Republic became fully independent in 1844, after several decades of occupation by Haiti and the Spanish speaking elite continues to portray this event in apocalyptic terms as escaping domination by the Black former Slave population of African origin in Haiti.The Dominican elites portray this event as the realization of their efforts to maintain the purity of Hispanic-Catholic culture and also in terms of “race” and “blood” much as the Inquisition portrayed the Judaizing “Marrano” population as a biological as well as national threat to Spain.

This concept of “Purity of blood” was an obsessive concern of the religious authorities in Medieval Spain that excluded and eventually forced the secular authority to expel all Jews (and then a century later all Muslims). It endured for centuries based on the biased belief that the unfaithfulness of the “deicide Jews,” was transmitted by blood to their descendants, regardless of their sincerity in professing the Christian faith. In much the same way, antihaitianismo came to regard anyone suspected of “Black blood” as Haitian.

The independence manifesto of the Dominican Republic states that ‘Due to the difference of customs and the rivalry that exists there will never be a perfect union nor harmony.” With the Haitians out of the scene, Dominican elites regained their privileged social position and their high-level administrative posts. Neither Spain nor France had the power or audacity to openly challenge the American Monroe Doctrine but both jockeyed for power while the United states was torn by the Civil War, and briefly sought to place a puppet on the throne of the former Caribbean colonies (France with its puppet Austrian Prince Maximillian, proclaimed Emperor of Mexico); and Spain in the Dominican Republic. The Dominican Restoration War was a guerrilla war between 1863 and 1865 in the Dominican Republic between nationalists and Spain, who had recolonized the country in 1861, 17 years after its independence.

The war against the Spaniards ended in July 1865 with Dominican independence restored but with the country devastated and disorganized by the “War of Restoration”, Haiti no longer planned to re-annex the Dominican Republic and even provided aid to Dominican patriots in their struggle against the Spanish. On the popular level however, these prejudices were reinforced.

Being Dominican soon became identified with being anti-Haitian. Dominicans were portrayed as devout Catholics, while Haitians were voodoo sorcerers who believed in spirits and utilized black magic in mysterious, perverse and erotic ceremonies. No matter how dark their complexions, Dominicans were portrayed as “white, the proud descendants of the Spanish conquistadores, while Haitians were truly black, and the sons and daughters of African slaves.

The Origins of Antihaitianismo

Spanish colonization of Hispaniola (the Spanish name given to the entire island) in the 16th century brought sugar, slavery, and racial prejudice with it. A minority white Spanish elite controlled the colony’s administration and ruled over a mixed population of creoles and slaves. Slavery existed, slaves were mistreated, and slave rebellions were severely punished and to a large degree, the color of one’s skin indicated one’s social standing and economic position.

This state of affairs changed radically with the growth of the French side of the island called Saint-Domingue. The French slave owning elite owned half a million slaves and a stronger economy so that the Spanish feared eventual loss of their culture. Haiti became an independent state in 1804 after a bloody revolution which was essentially a slave uprising. Dominicans felt betrayed by the mother country when Spain ceded the colony to France in 1795.

The Santo Domingo colonists, regardless of their color, soon started calling themselves as “blancos de la tierra”, in essence a native- born creole white population. The wealthy Dominican elite further resented being sold out to the “inferior” black ex-slaves. This mattered most of all to those individuals who had been raised with the hierarchical values of Spanish society and who saw Haitian army officers with little or no education. Later Dominican leaders such as Rafael Trujillo and Joaquín Balaguer would comment that Santo Domingo lost most of its “best” families at that time.

The Parsley Massacre—1937-38 Genocidal Attacks and its Biblical Forerunner

The Parsley Massacre occurred in October 1937 against Haitians living in the Dominican Republic’s northwestern frontier region and was carried out on the direct orders of the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. The death toll has variously been placed at from 12,000 (Dominican estimates) to 35,000. In 1975, Joaquín Balaguer, the Dominican Republic’s interim Foreign Minister at the time of the massacre, put the number of dead at 17,000.

This was followed in the spring of 1938 when Trujillo ordered a new campaign in the southern border region and lasted several months during which thousands were forced to flee and hundreds were killed.Not just the army was involved; Local Dominican citizens took part was well.These operations took their name from a technique employed thousands of years earlier and recalled in the Bible. Since skin complexion was a very uncertain matter of determining identity, Haitians were asked to pronounce the Spanish word for parsley which is perejil.

The “j” letter followed by a vowel has a guttural sound in Spanish like the “ch” in the way Scots pronounce the word loch as in Loch Ness. The French speaking Haitians find it very difficult to pronounce this sound. The same technique known as a Shibboleth was recounted in the old Testament in The Book of Judges (Judges, 12:5-6). The Ephraimites were unable to correctly pronounce the “sh” sound commonly employed by the Gideonites.

This same clever ploy was used in ”Schild en Vriend” (Shield and Friend) 1302 when Flemings found French soldiers disguised as peasants by forcing them to repeat the expression and again in World War II when Dutch Resistance fighters were sometimes able to uncover German spies unable to pronounce the Dutch “sch” sound in the name Scheveningen, an important resort city in the Netherlands. Thus, a shibboleth is any outward way of determining someone’s true identity.

Rafael Trujillo, 1933

The barbaric killings of so many civilians including many women and children was largely unreported abroad due to the fact that the army had murdered and buried the victims en masse in isolated rural areas, leaving either no witnesses or just a few survivors. The extraordinary violence of that unfortunate episode was not an isolated incident and anti-Haitianism has continued to grow over the last sixty years until the present. Most Latin American governments have preferred to keep this issue untouched, much like the Inquisition, as it reflects badly on the shared proud heritage of Hispanidad and “La Raza.”

Latin American dictators Trujillo, the Cuban Fulgencio Batista (supported for many years by the Cuban Communist Party) and Argentinian dictator Juan Peron were all arch pseudo-populist “heroes of the people” or the “working class” for a time, who cynically played all sides for advantage. Trujillo gained good publicity in the United States during 1939-41 by allowing a handful of Jewish refugees to settle in the country to obscure his criminal and reprehensible conduct.

At the 1938 Évian Conference in France, it offered to accept up to 100,000 Jewish refugees. A Dominican Republic Settlement Association was formed to help settle Jews in Sosúa, on the northern coast. About 700 European Jews of Ashkenazi Jewish descent reached the settlement where each family received 82 acres of land, 10 cows plus 2 additional cows per child, a mule and a horse, and a US$10,000 loan at 1% interest.

Other refugees settled in the capital, Santo Domingo and by 1943 the number of known Jews in the Dominican Republic peaked at 1000. The Sosúa’s Jewish community experienced a deep decline in the 1980s due to emigration. This window dressing was a good stunt to cultivate better relations with the U.S. and calm unsettled nerves in the U.S. State Department which was aware of the massacres of 1937-38.

La Isla Al Revés; Haití y el Destino Dominicano

Anti-Haitianism has also left an important literary legacy behind. Joaquin Balaguer, Dominican Foreign Minister and three times President of the Dominican Republic (1960 to 1962, 1966 to 1978, and 1986 to 1996) and often referred to as “The Intellectual Backbone of the Trujillo Regime” wrote an excuse for anti-Hatianism although expressing “sympathy (largely crocodile tears) titled “La Isla Al Reves” – The Wrong Way Island attempting to defend Dominican efforts to shield itself from encroachment by its “powerful neighbor.”

Balaguer used the same arguments in a campaign against political rival Peña Gómez whose partial Haitian ancestry was exploited. Dominicans historically have a deep fear and mistrust of anyone with Haitian blood. Balaguer claimed that Peña would try to merge the country with Haiti if elected. When the returns were announced, Balaguer was announced as the winner by a mere 30,000 votes.

Many of Peña Gómez’s supporters showed up to vote and learned that their names had vanished from the rolls. Peña Gómez screamed fraud, and called a general strike.

Investigations also revealed that about 200,000 people had had their names removed from the polls. Amid such questions about the poll’s legitimacy, Balaguer agreed to hold new elections in 1996—in which he would not be a candidate but in the end managed to get a coalition candidate approved.

If anything is to be gained by a study of the current situation in American politics, the glass is more than half full, it is overflowing; while in the Dominican Republic it is empty.

The American political left and leadership of the Democrat Party have gravitated away from the original “Liberal” concepts of equality of citizens before the law and ignored the distinction of citizenship. In so doing, many American citizens have now come to feel progressively disenfranchised. Many thousands of formerly Dominican citizens of Haitian origin have been deprived of their legal rights and expelled by administrative fiat, the grandfather clause and ex-post facto laws. These are the techniques of a “Banana Republic”.

The polar opposite situation has prevailed in the United States for more than a generation during which illegal migrants have been granted the right to remain indefinitely and the present exploitation of legal immigration procedures when illegals bring minor children with them or send them on ahead.

The United States has succeeded in making good in deed rather than just in word the promises of the Declaration of Independence that all their citizens enjoy equal rights and equality before the law regardless of race, religion, gender, place of birth (If they have become naturalized citizens), and ethnic origin. This is something to be proud of and must not be lost sight of in the current bitter debate over illegal migrants, i.e. those who are NOT citizens and have both entered and remained in the country illegally.

Unofficial Flag of Hispanidad (Hispanicity)

P.S. Mention of the 1937 Parsley Massacre in Literature

The massacre is a focus of Jacques Stephen Alexis’ 1955 novel General Sun, My Brother.

The Parsley Massacre is chronicled in the novel El masacre se pasa a pié (The massacre crossed on foot) by Dominican author Freddy Prestol Castillo.

When Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel The Feast of the Goat, mentions ‘What do five, ten, twenty thousand Haitians matter when it’s a matter of saving an entire people’, it refers to the justification of the 1937 ethnic cleansing parsley massacre of all Haitians in the Dominican Republic border area.

______________________

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link