by Pedro Blas González (February 2023)

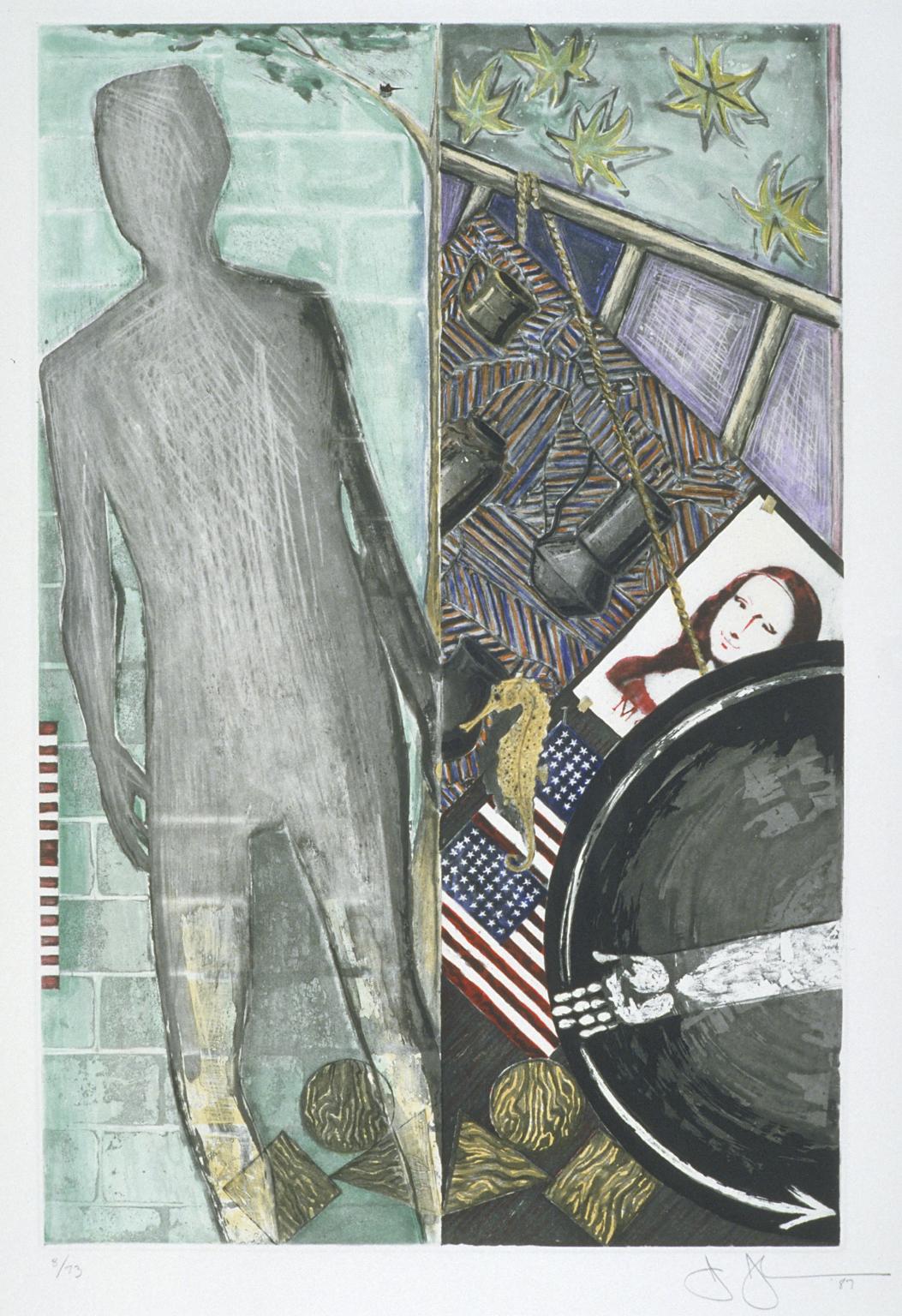

Summer, Jasper Johns, 1986

And if truth is one of the ultimate values, it seems strange that no one seems to know what it is. Philosophers still quarrel about its meaning and the upholders of rival doctrines say many sarcastic things of one another. In these circumstances the plain man must leave them to it and content himself with the plain man’s truth. This is a very modest affair and merely asserts something about particular existents. It is a bare statement of the facts. If this is a value one must admit that none is more neglected. —W. Somerset Maugham

Dawn

First there is morning—primeval morning of eternal consequence. The only discernible movement in this initial parting from form belongs to the dew, stretching down from the leaves. The absence of sunlight makes this primary manifestation of Being elusive. When does the separation of essence from Being first take place? When does the impermeability of Being become splintered with a vagrant multiplicity?

The first morning determined the tonic of time. In its first phase, the dethronement of understanding by reason castrated Cronos into oblivion. This cosmic falling out was clouded in mist, giving subsequent observers the misguided impression of an occluded reality. This was the last vestige of imagination. When the mist of this primordial morning cleared, the world already felt weary and old. To counter this early fatigue imagination turned into vital will.

Imagination demands of its practitioners to be rooted in a conscious will. If most fail in this task—the answer is comically clear: the senses and the over-luminous brightness of midday have forever ensconced man in a failed material condition.

The Second Morning

The second day breaks, veiled by a heavy blanket of dew that covers the harshness of the land.

In the distance … a figure walks gallantly toward the horizon. He holds the sun high above his head. Flinging the giant sphere into the void of space, he settles down to admire his work—his tenacity. A smile drips from his mouth, as he sits on the wet ground to praise his vision.

From the opposite horizon another figure quietly emerges from the young chaos of this emanation. Zeus grabs Prometheus by the back of his neck, as the younger man struggles to free himself. He scolds him: “Indiscretion is born of ill-reasoned thoughts—and negation.”

As a ghastly eagle feasts on Prometheus’ liver high on Mount Caucasus, his patience intensifies. Anticipation becomes ossified. Awaiting the next night that brings renewal, he becomes irreverent—proud.

The following day the eagle returns—Prometheus waits in guarded expectation—he flinches with the initial stab of pain; suffering becomes part of the order of things.

“What to do?” he asks.

He seeks counsel from his friend Sisyphus.

In the second volume of The Mystery of Being, the French existentialist, Gabriel Marcel (1989-1973), convincingly argues that to philosophize is to think sub specie aeternitatis. That is, human existence viewed in relation to the eternal. Marcel anticipates a question that postmodern critics gloat over: is reflection on the nature of the self a form of ego-centrism? His answer is resoundingly clear.

Marcel reasons that sooner or later thoughtful people must embrace self-reflection, often for self-preservation. This initial discovery is founded on the understanding that the reality that we experience as a subjective—I is only one aspect of objective reality. Thus, we come to the realization that subjective reality—human existence—is surrounded by an objective realm.

Marcel’s thought is illuminating. He understands that all reflection on the nature of the self must posit the fullness of life as a starting point. Abstractions inspire very little in terms of vital, existential existence. But to say that the self is surrounded by objective reality does not entail that it is readily absorbed by it. On the contrary, the subjective-I seeks to establish this demarcation point. The “bite of reality,” as Marcel has referred to this outer reality, in effect has a disquieting and centralizing consequence that keeps the thinker humble. Ego-centrism, whenever this occurs, only results from wearing blinders.

Let us consider why anyone should be concerned with subjectivity? After all, what advantage is there in giving oneself over to philosophizing on the nature of existence given the degree of distress that life naturally exhibits?

Why is it essential for thinkers—also poets of old—to become burdened with the essence of their being, to become bogged down with such weighty affairs? It is not necessary to open up a Pandora’s box by addressing the complexity that Being suggests. The days of hair-splitting for the sport of it have not only failed to benefit man, but have served as a detriment to vital philosophy. Being is the underlying substance of any existent—that is, of self-standing, self-subsisting reality.

Why concern ourselves with the nature of the self? Are the answers to such questions not categorically flexible enough to quench our existential inquietude? The Spanish philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, penetrated into a fundamental truth of the human condition when he answered this concern by suggesting that the value of this question is tied to human harmony. I will add that reflective persons are artisans of vital thought, of cohesion. The unitary and cogent vital understanding that existential reflection seeks originates in self-reflection. It is vital truth that man hopes for, while still respecting the dictate of naked reality.

Naked reality, Ortega contends, has us discover ourselves in the midst of a totality, of a tributary of things and people that exist outside of the self. Man seeks to know out of necessity—the latter as a tool for living. This realization eschews abstraction.

If thought is an essential tool for a meaningful and contented existence, the question still remains as to what type of reflection is best suited for this vital task? One example of the type of thought that is not well suited for self-understanding is that which focuses on external objects or stimuli. For this reason, science is quickly discarded as a suitable vehicle for self-understanding. If we need further convincing, we only need to look at objective contingencies. Human existence is not equivalent to human life. While human life can be explained in a quantifiable biologism, the former demands of itself an existential account of time and vitality that can only be expressed through self-autonomy.

The passage of time weaves out the value of thought and all that has been said, written, suggested, and forced upon man by motives that often fall short of the love of truth. I would argue that the history of the maxim as a genuine form of human communication deliver us to truth.

No doubt that temperament and vocation inform individual human existence. Regrettably, putting man in a collective container is more expedient a solution to human concerns than to embrace personhood as differentiated: as self-reflecting, individuals. Lamentably, many people want to belong to clans. The embrace of human autonomy comes at a profound personal price. Reflection on the human condition brings us to the realization that the essences that inform human existence are not readily quantified.

In the Sumerian work of wisdom literature Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh takes on the powers of life and death as he scours the world searching for immortality after his young friend Enkidu passes away. Not surprisingly his incessant fight is taken to a higher court of appeals than his elders can advise him. Gilgamesh is a microcosm of proto-subjective man.

Albert Camus embraces Gilgamesh’s ethos in both The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel, where an inwardly vital intuition is stoically directed at life itself. Neither of his two major works vent their scorn, or plead for mercy, as the case may be, to political powers or institutions, which in the final analysis, fail to supply man with contentment, if not happiness.

Socrates grounds knowledge in what is essential: self-knowledge, auto-gnosis. After entertaining the concerns of earlier thinkers, he turns his attention to the conviction that man’s most pressing problem is self-knowledge. For Socrates, the highest value is rational life, which exemplified by the moral life. Socrates’ dual quips “Know thyself” and “The unexamined life is not worth living” spring from the autonomy of the individual.

What advantage can life viewed from within offer man in a dark, technological age? This question seems especially pertinent in postmodernity, when human problems are confused with those of the natural sciences. Today, a segment of the human sciences negates the human person by imitating the scientific method.

It has still not dawned on materialist thinkers that the methods of science and existential reflection are not mutually agreeable. Technical problems are closed-ended in scope, that is, they are solvable, whereas existential questions are open-ended and must be addressed by individuals.

No amount of fashionable ‘theory’ can succeed in negating human reality. It is for this reason that technical questions are often easier to address than human questions. Today, what man demands of science is not knowledge, rather an ever-expanding technology. Human life—human existence—when viewed from the inside is a fragment of reality, but a central fragment, nonetheless. These are the conditions that life sets for us.

The possibilities for philosophy have never been greater and more fruitful, yet more tragically squandered. For philosophy to become relevant once again, as the grande dame of humanism that she once was, it must strive to offer insight into questions of vital importance for individuals, not theoretical refutation of reality. The days of analytical hair-splitting, self-referential word play, social-political canvassing, and self-loathing abrogation have proven to be detrimental; an embarrassment to thoughtful persons.

The nobility of philosophical vocation is best appreciation when viewed as a tool in the service of life. What is at stake is nothing less than the soul of man, not as an empty caricature that is refuted by ‘theory’ but as the ground of vital possibility. Today the humanities resemble a man who, after waiting for hours at a station for his train to arrive, realizes that trains have become extinct.

A new approach beckons—one that eliminates pedantry and theory, and which embraces a vital, real-world reconstitution of the human person. The focus of this task should be to treat human existential vitality as if it actually matters. Individuals steeped in this enterprise make no greater claims than to salvage their own temporal existence. What binds thinkers to this vital task has less to do with abstraction and post-modernist theory, and more with flesh and blood, time-keeping, real world subjects.

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

The problem, simply and adequately stated, is our refusal to discover the answers implied in the Diamond Sutra, Heart Sutra, and Advaita Vedanta explanations

Philippians 4:8 and Castaneda’s ‘Paths With Heart’ await to guide the traveler. Why wait? Another book is unnecessary.