Recollections and a Relic of Sylvia Plath

by Jillian Becker (November 2020)

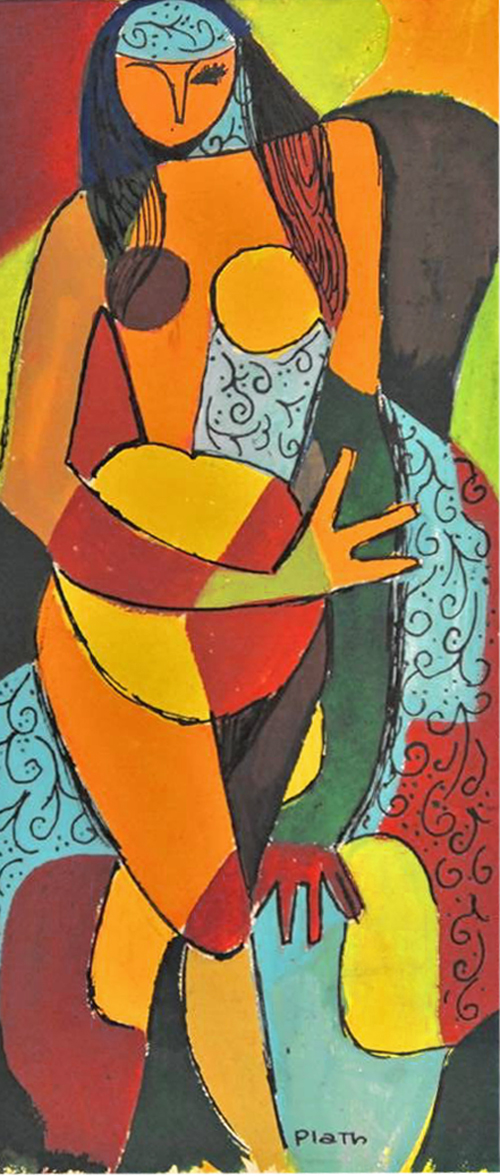

Study of a Woman, Sylvia Plath

Fifty-seven years ago Sylvia Plath spent the last days of her life at my house in Islington, London, went home and killed herself. Very early in the morning she turned on the gas in her oven, laid a folded cloth on its floor and her head on the cloth, and died.

She was thirty years old, as also was I.

A week or so later a woman journalist with Time magazine came to ask me about Sylvia’s last days. The published (unsigned) article suggests that had we—my husband Gerry and I—kept her with us longer, she might not have killed herself. We had “let her go too soon.” The writer did not say how we could have stopped her going. If there was something we could have said or done to prevent her suicide, I still don’t know what it is. If her small children were not reason enough for her to live, what better reason could there be?

Recently looking through long unopened files of documents concerning Sylvia, I found some pages that interest me more now than when I first read them.

In letters written to her mother around the time she met Ted Hughes—pages which Aurelia Plath herself copied and sent to me—Sylvia extravagantly, even ecstatically, praised him, but already believed she saw terrible faults in him.

May 3, 1956

. . . I have passed through the husk, the mask of cruelty, ruthlessness, callousness in Ted and come into the essence and truth of his best right being. He is the tenderest, kindest, most faithful man I have ever known in my life . . .

But it wasn’t just a mask. She knew it, and—she wrote—he knew it too:

May 6, 1956

. . . Ted says himself that I have saved him from being ruthless, cynical, cruel and a warped hermit, because he never thought there could be a girl like me, and I feel that I, too, have new power by pouring all my love and care in one direction to someone strong enough to take me in my fullest joy . . .

When I met her in 1962[1], “most faithful” Ted had deserted her and was living with a woman who was pregnant with his child. Sylvia was coping with two very young children on her own. She was short of money. Her widowed mother was repeatedly warning her that being a lone parent would be hard. And she was being medically treated for depression, from which she had suffered—recurrently if not chronically—for years.

Most of the people she had thought of as her friends were avoiding her.

“Everybody hated her,” Ted mumbled to Gerry and me, though as if talking to himself. He said it without looking at either of us when we were sitting, one on each side of him, at the end of a long table, having dinner with a dozen or so others, in the private room of a pub after we’d all attended Sylvia’s burial in the snow-covered graveyard at Heptonstall. To bury her there, where his parents lived, was Ted’s choice. She had told him in days past, when she had been happy and not expecting to die soon, that she would like to be buried in the shady cemetery near Court Green, their Devon home. She would not have consented to the windy heights of a bleak, hard, Yorkshire mountain.

Ted’s father, a young woman cousin, and some of his Heptonstall relations or friends were “there for Ted.” Sylvia’s brother Warren, his wife Margaret, Gerry and I were “there for Sylvia.”

We had come on a long train journey. The cousin met us in the early afternoon at Hebden Bridge station, drove us up the mountain to the grey, flinty village of Heptonstall and the Hughes family’s house, and introduced us to Ted’s mother and father. Mrs. Hughes seemed to me a threatening presence, reticent, dour, disdainful; stout yet hard as the rocky heights of her Yorkshire home. I felt her every glance at me to be a reproach—not for letting Sylvia die, but for having been on her side. Her demeanor was of one who felt personally insulted and imposed upon by the events that necessitated our presence which, however, she would bear stalwartly, uncomplainingly. She did not come with us when we set off on foot for the church and graveyard higher up the mountain. I remember Ted’s father as a thin man, slight in comparison with his wife and son, even more silent than she, but not in the same grim way. As I stood beside him at the graveside—where for a few moments a thin shaft of watery sunlight made a wall of the pit and the yellow mud piled on the brim of it glow—I felt that he grieved a little for Sylvia.

It was not true that everybody hated her. I didn’t, I told Ted. And Gerry said he didn’t. We both looked to see if Warren could have heard Ted’s murmured remark. He surely had not. He and Margaret were at the other end of the table, listening to other voices.

Ted ignored what we said. It was of no interest to him what we felt about Sylvia. If everybody had hated her, hateful she must have been, and her hatefulness vindicated his desertion of her and his adulterous affair. And by “everybody” he meant his friends, the poets of his circle and their wives. Especially their wives.

Dido Merwin, a wife of the American poet W. S. Merwin (who died last year), was one of them. I met her one winter’s night at a dinner party some thirty years after Sylvia’s death. I drove her to a house where she was staying with friends, not far from my own. I said an affable goodnight to her. She did not move. For an hour or more, as we sat in the car, in the cold, on the dimly lit street, she told me stories to illustrate her contention that Sylvia had been a most unpleasant person, ungrateful and selfish. I was to understand—she demanded—that Sylvia had driven Ted away and yet dared to complain that he had deserted her. When Ted and Sylvia came to stay with her and her husband in France, she said, Sylvia had helped herself to all the food in the refrigerator. She talked as urgently as if she had a last message to impart to the world and could only do it through me (though she also wrote the stories for an appendix to a biography[2]). She died not long afterwards. The message I got from all she said was that Sylvia was guilty of domestic cruelty and food theft, and Ted was innocent, and it mattered very much that the world should know it.

Ted’s sister Olwyn, a fierce guardian of his reputation, concurred with Dido’s verdict. She invited me to lunch in a Chinese restaurant in London with a biographer of Sylvia (the one whose book includes Dido Merwin’s testimony). Like her mother, Olwyn was dour and disdainful—but not reticent. She presided over the meeting, dictating what parts of the information I gave the writer might and might not be allowed to enter the record.

“She made me professional!” was another complaint Ted made to us the night after Sylvia’s funeral.

That was true. But was it a bad thing? Had it harmed him—or had it made him?

Sylvia wrote:

May 18, 1956

. . . I’m starting to send batches of Ted’s poems out to American magazines because I want the editors to be crying for him when we come to America next June. He has commissioned me his official agent . . .

Through all her emotional storms, Sylvia remained efficiently “professional” to the end of her life. She left her unpublished poems neatly typed, ready for publication.

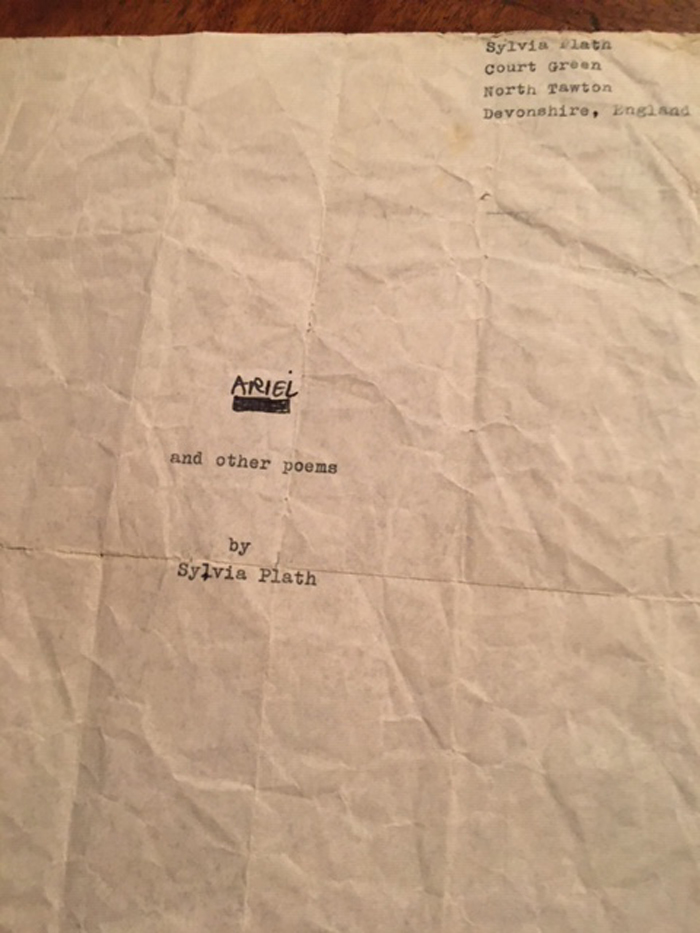

One of the pages I found in the long-neglected files shows that when she assembled the poems for her second collection, she changed her mind about its title. She typed a word in the center of a cover page, but blacked it out with a pen and typed another word above it. Later she discarded that page. It came in handy as a piece of scrap paper to hand to my husband when he needed to jot down her name and address for the mechanic who was fixing her car, so he’d know where to bring it home. But the page stayed with Gerry. Folded in four, the back visible, it lodged in the file where I found it.

It’s a flimsy sheet, tattered at the edges. I unfolded it carefully, saw the correction, and to find out what her first choice had been, held the page over a bright lamp. I could see the five capital letters beneath the black ink. They spell DADDY—the title of her most famous, most frequently quoted poem.

An angry poem. Written in a thumping doggerel as if she were stamping on the grave of her father[3]—if not of poetry itself:

You do not do, you do not do

…

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your goobledygoo.

And your neat moustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue,

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You—

. . .

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

. . .

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.

The poem declares that there was another man, another “Fascist” whom she had married and was equally and simultaneously done with:

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

….

If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two—

In the same volume are more angry poems; poems of seething hate and repudiation; poems about suffering, sickness, suicide, with images of horror.

There are also some about love for her children, with charming images.

And there are two about a passion for experiencing furious motion.

From one of them[4]:

What I love is

The piston in motion—

My soul dies before it.

And the hooves of the horses,

Their merciless churn.

From the other[5]:

Something else

Hauls me through air—

Thighs, hair;

Flakes from my heels.

White

Godiva, I unpeel—

Dead Hands, dead stringencies.

. . .

And now I

Foam to wheat, a glitter of seas.

. . .

And I

Am the arrow,

The dew that flies

Suicidal, at one with the drive

Into the red

Eye, the cauldron of morning.

Her consummate thrill, the poet claims or confesses, would be a purposeful hurtling into death.

Sitting at her typewriter, in tranquility, Sylvia considered what the title of the whole collection should be. Should she shop-window the chant of hate, accusation, rejection; the howl from a victim, a survivor of sadistic deception and betrayal by a father and a husband with both of whom she was “through”?

Or should she rather stress the importance of that very different poem, the paean to intensely exciting life ending in a splendor of self-destruction; a poem in which she was an avatar of power, extremely alive, choosing to immolate herself in the vast cosmic event of dawn?

She chose the first. She titled the volume DADDY.

But then she thought again. And made up her mind. Her final—sober—choice was the shout of joy on plunging into death.

She blacked out DADDY and wrote ARIEL.

[1] Forty years later I wrote a memoir of my relationship with Sylvia: Giving Up: The Last Days of Sylvia Plath, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2004.

[2] Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath by Anne Stevenson, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1989.

[3] From the poem Daddy.

[4] From the poem Years.

[5] From the poem Ariel.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal (Europe), Encounter, The Times (UK), The Telegraph Magazine, and Standpoint. She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast