Remembering Don Emilio

by James Como (January 2020)

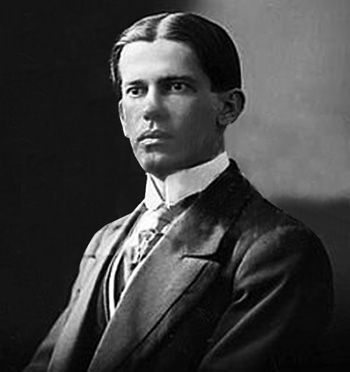

Jose Emilio Ulises Delboy Dorado, 1912

The small note taken of some figures from the past is often contra-indicative of their actual noteworthiness. Take, for example, these figures, of whom you’ve probably never heard . . .

Read more in New English Review:

• Tom Wolfe’s Mastery of Postmodern America

• Politicizing Language

• The Theology of Edgar Allan Poe

He was of average weight for a man of five foot eight inches or thereabouts, not small by Peruvian standards of the day. In dress and manners he was a gentleman of his age, a world very nearly gone by in the Northern hemisphere but enduring in Peru. He was also a man of his socio-economic class, the white upper middle class (in those days, but no longer, a redundancy), which meant domestic servants, and always a butler.

I met him (further on I will recall those meetings) shortly after our marriage when Lima was still the city that he had known most of his life, more or less equivalent to our thirties, especially its automobiles, carcochas that were the colectivos, or ride-shares avant la lettre. Downtown was elegant, the very old colonial buildings not yet falling-down shabby, the boulevards clean. Streetcars took you to the outer precincts.

Yet, though large swaths of Peruvian society ran (and run) on racial distinctions, he would have none of it: no slurs, no discourtesies, never a hint of sneering contempt. Withal he was proper, as a cosmopolite is wont to be, neither indecent in language nor condescendingly familiar with staff or strangers. He was also uncompromisingly literate, in Hispanic, in other continental, and in English literatures (read in English). He favored history and biography, a learning he wore lightly.

In short he was a cultivated man who, having done brave deeds and known much adventure, was neither posturing, exhibitionistic, nor fraudulent in any way: his self-respect and innate dignity would have allowed nothing of the sort

Sometime in the nineteenth century a Delboy (likely another Bernard) was diplomatically dispatched to Peru, where he fell in love, with both the country and a siren (don’t I know) and so began the Peruvian branch. Not long thereafter my father-in-law came along. His parents, Maria Rosa Dorado and Mariano Emilio, sent him to the naval academy, but he fled to the jungle, where he would spend a good deal of his young life in various positions, and then in exile to America.

In 1915 he received an honorary Doctorate in Letters from the University of San Marcos (the first university in the new world). Thereafter the achievements I’ve mentioned in the second paragraph above would begin, punctuated by various high-level government positions. By his late forties he was that man of many parts, and known as such.

Then came Hitler, whom he loathed. After Emilio denounced him in the assembly (widely covered by the South American press), Churchill invited him to England. There he met that great man and another, de Gaulle. He writes to Maria, my future mother-in-law, who has already given birth to the architect: “yes, do buy the nylons you need, for here [England] you cannot find them.”

From there he again visited America, which he loved dearly, not least New York (an enduring affection: his AP office was at Rockefeller Center) and Hollywood. From there he wrote to Maria, “Gregory Peck signed a photo for you, but your dear Lorenzo wasn’t in town”—that was Olivier.) He wrote for the New York Times, for the Associated Press, for the Peruvian Press Alliance, and spent an afternoon with Eleanor Roosevelt, who was charmed.

Eventually he and Maria would separate, so he writes and life goes on. Nearly twenty years later I come along, knowing nothing of what I’ve written above. Yes, he was a man of some distinction whose time had passed—very old school, once a writer, and—and that was it.

We met three times, I already married to his daughter. The first meeting, arranged by Alexandra, was in his home: merely an introduction. That home was exquisite and included colonial silver, antique furnishings, and pieces hand-made to his taste. The books in his impressive library were leather-bound, and more than one original masterpiece hung on his walls. We chatted briefly and arranged a night at the theatre later in the week. He was fine company, affable, relaxed, and eager that I be relaxed, too. The theatre played a zarzuela, a picaresque Spanish musical review.

The third meeting remains a landmark. He invited me to lunch at the Union Club, where his membership stretched back several decades. Of course the serving staff knew him well and were clearly fond of him. I forget what we ate, but I do know that I drank slightly more than the single half-glass of wine that is my norm, and two, I think, pisco sours (virtually the national cocktail: very sneaky).

We conversed. By now I had learned more about the man and so, for a spell, practically interrogated him. He would interrupt to ask about me, as though I were as interesting. He did want to know about my teaching, my college and its students, and, especially, about my subject. When I mentioned rhetoric he was particularly impressed, apparently re-assured that it was still taught and that his beloved daughter’s husband esteemed it highly. His curiosity was palpable.

But, of course, no matter his genuine show of interest in me, I could never be as interesting as he, though one remark opened the door to genuine mutual admiration. When he asked for an example of my teaching of rhetoric, I mentioned that I used as a model the greatest orator of the century, and the one, after Lincoln, whom I most treasured.

“Please, tell me who that could be.”

“Oh, Churchill, of course—a hero of will, intellect, and moral sentiment, all wrapped in unequaled eloquence of unforgettable power.” He very much liked that, smiling and nodding all along.

Then he dropped the bomb. “I knew him, you know, and I’m delighted to tell you that he was all you’ve described, and more.” I was stupefied. He told me of a walking tour with Churchill, and of an inspection of armarments—and finally of a late-night meal preceding an all-night drinks fest. “Peruvians are supposed to be able to drink alcohol, the way Americans are expected to golf. So I was accustomed to carrying myself well, pacing myself. But I’d never seen anyone drink the way Churchill could—and stay coherent, and more than coherent. Sharp, witty, even eloquent.”

The highlight of the evening came late, when Churchill discovered that Don Emilio had written verse. (In fact, the Spanish lyrics to Piaf’s “Le Foule” are his.) Well, so had he. Oh, answered the Peruvian, I hadn’t heard. “Yes, here’s one.” And according to my father-in-law, Churchill recited one of the funniest and filthiest limericks Emilio had ever heard.

“Do you suppose it was impromptu?” I asked.

“It sounded so, though his recitation was so uproarious I assumed he must have trotted it out before.”

I asked what happened then, and Don Emilio answered, “I did the only thing a gentleman could do. I recited one of my own—and by his own admission it topped his!” That went on for quite a while, until the two men realized they were facing an early day and that surely a few hours sleep were in order. I asked his assessment of the great man. “Greater than you’d expect. I’ve never met a grander man, anyone who understood hospitality and friendship more deeply.”

He seemed moved by the memory, so thinking to take things down a notch I asked if he had met de Gaulle. “Ah yes. The coldest, most off-putting person I’ve ever known. I found nothing to like.”

Our lunch ended and I rode home with him. He invited me in. “I have something for you.” He gave me a book, a one-volume abridgement of Churchill’s own The World Crisis, 1911-1918, inscribed to him by Churchill. Before handing it over he inscribed it to me. Eventually two other objects found their way into my wife’s possession. One is a photo of de Gaulle inscribed by him to Don Emilio as an “ami de la France.”

Read more in New English Review:

• The Theology of Edgar Allan Poe

• Two Literary Sermons

• Good Masculinity

I lament that I had not known the man sooner, let alone in his salad days, that I am distant from him and can offer only this thin profile with an even thinner memoir. But his daughter was not distant. Here is Alexandra’s much more revealing look at her father . . .

The first memories I have of my father are our Sunday morning visits to the house he shared with his wife and two small children. Early on that morning, my mother would dress me carefully, always with the prettiest frocks, do my hair with the little braids on each side of the temple and tied together with a flamboyant bow. The last detail was a close look at my fingernails, ensuring they were perfectly trimmed and neat, “because your father likes pretty hands.”

My brother (eight years older, and probably around twelve at the time) and I would be put into a taxi and taken to our father’s house. We were received by his butler, Bolivar, not his actual name: my father would re-name all his butlers ‘Bolivar’ after his favorite hero of the War of Peruvian independence. I remember two Bolivars in my time.

We would then go up to the library and spend time talking, he introducing some English phrases into our conversation. My brother was already attending a British school, and our father wanted me to learn English as early as I could. He had all the newspapers of the day spread on the table, as well as a variety of the American magazines he subscribed to: Colliers, The Saturday Evening Post, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and of course Look and Life. And there was his ‘receiving tray,’ a silver platter always filled with cards inviting him to this embassy or consulate, that official state function.

I entertained myself looking at the pictures of the magazines, curious, asking all sorts of questions about that world far beyond ours. It was at that time that the familiarity and affinity with the country that would be my own, and my children’s, was born. I also loved the warmth and the feeling of safety that being surrounded by books provided me. The discovery of the different kinds of books and bindings had a magical effect on me, as did the opening and closing of little drawers containing all sorts of stationery. I suppose the lack of stability ordinarily provided by the domestic presence of a father was compensated for by these Sunday morning rituals, rituals that have left such an indelible mark on me. I realize now that my father expressed his tenderness through books, his teaching me to love them, to search in them for the answers to all questions.

For example, in the most indirect way he sparked my interest in Napoleon and consequently in French history that developed into a life-long devotion to history in general. He had a canary he called Ney. I asked him why he had called him that, and what kind of name was Ney anyway? He replied that he called him Ney because he seemed like a brave little bird, just like the bravest of Napoleon’s marshals. Who is Napoleon? When you are a little older and you learn to read, you will read the books I have about him, the saddest one of all being, in English, The Memorial Of Saint Helena. When I was eleven years old I could finally read it.

My first movie crush was on James Dean, whose middle name was Byron. When I mentioned this to my father he reached up and took from a shelf Maurois’ biography of the poet. That, too, changed my life. There was the answer, in a book, and there was my father with book at hand, showing me where answers lay.

He also was an answer.

Alas, this most noteworthy of men was forgotten by the world, in particular by those smaller worlds he served so well, of Peruvian diplomacy, politics, journalism and exploration. But he was not, must not be, forgotten by those to whom he mattered most. And the wider world, too, should take note.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

James Como is the author of The Tongue is Also a Fire: Essays on Conversation, Rhetoric and the Transmission of Culture . . . and on C. S. Lewis (New English Review Press, 2015). His most recent books are C. S. Lewis: a Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2019) and The Folk Tales of Brusco and Giovanni, in three books (KDP, 2020).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast