Remembering the Danish Minority in Nazi Germany

by Norman Berdichevsky (May 2023)

War and Peace, Henry Heerup, 1945

In doing research on a book about the border dispute between Germany and Denmark, I came across a fascinating and unexpected example of how the ethnic Danish minority in Southern Schleswig, subject to intense Nazi pressure to conform, resolutely resisted by asserting its own values and proved to be an inspiration to the local disheartened Jews. The latter had gone from believing they were loyal and patriotic Germans to a despised outcast group of social pariahs. This story deserves to be told and made more widely known in our own chaotic world, so lacking in moral constancy and opportunistically seeking only the most expedient way out of difficult situations.

Denmark quite rightly has won an honored place among many Jews in both Israel and the Diaspora for its famous rescue of almost the entire community in October 1943, a brave humanitarian operation that has become a legend. Wholly unknown to foreigners is another courageous gesture by ethnic Danes residing in South Schleswig, reduced to a minority under constant pressure and subject to harassment and intimidation by the Nazi regime from 1920 to 1945. The Danish minority’s situation in Nazi Germany is of interest because it represents the only non-German community that the German government could not simply capriciously ignore or mistreat with impunity (as it did towards the Jews, Poles, Czechs, Lithuanians, French-minded Alsatians, Frisians and Sorbs) but had to try to accommodate in some degree in order to ensure good relations with Denmark, a policy which German foreign policy sought to promote. The Danish minority, whatever the views of its individual members towards the Nazis’ racist ideology and in spite of sympathy towards Denmark in the face of naked German aggression in 1940, had to obey German law and fulfill all their duties as German citizens including military service.

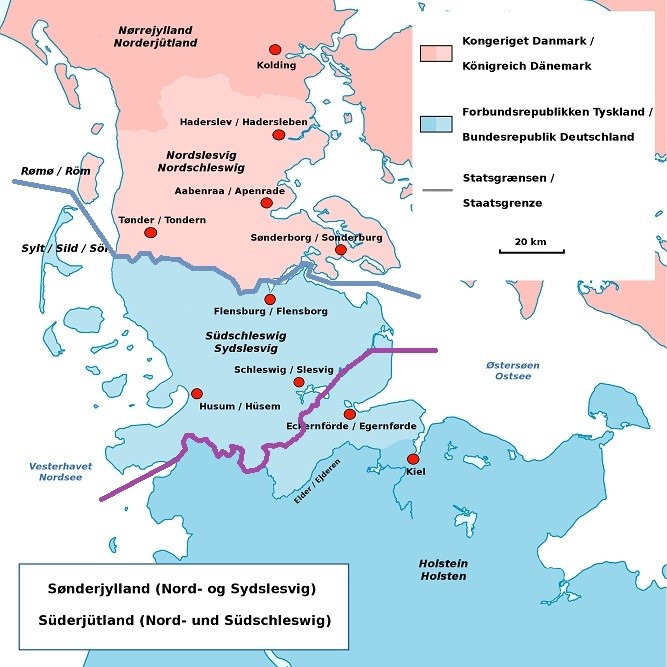

The voters in the area in pink (North Schleswig) voted by a decisive majority to reunite with Denmark thereby ending German occupation dating from the loss of the territory in the 1864 Second Schleswig War. Prussia and Austria acting as allies defeated Denmark in a quick and decisive war followed by an agreement to jointly administer the territory but quickly quarreled. As a result, Prussia seized all of the old formerly Danish controlled areas. This ignited pan-German nationalism resulting in the proclamation in 1870 of a united German Empire eclipsing Austria.

Approximately 6,000 North Schleswigers (the overwhelming majority Danish-minded) fell in German uniform between 1914 and 1918 for a war that they viewed with little or no enthusiasm in contrast to the German-minded population’s vision of even greater national aggrandizement.

During 1914-1918, their fatalities were higher than the national German average. Several hundred Danish-minded North Slesvigers took advantage of nearby Denmark to flee across the border and either avoid conscription or desert.

Most supporters of the Social Democratic opposition in the northern districts of Flensburg, several other larger towns (Schleswig, Husum) and among day laborers who were still identifiably Danish in their sympathies were nevertheless swayed by the opportunity to become a part of what they envisioned and hoped would be a democratic republican industrial Germany. This seemed more attractive to the urban working class than an enlarged but monarchist and still largely agrarian Denmark.

There is still a considerable Danish community in the town today. Some estimates put the percentage of Flensburgers who identify with it as high as 25%, although in the 1920 plebiscite, no more than 10% voted for incorporation into the Danish kingdom. The SSW political party in the region representing the Danish minority today usually gains 20–25% of the votes in local elections, but by no means are all of its voters ethnic Danes. Before 1864, more than 50% of Flensburg considered themselves as Danish. Today they are a minority but a large number still have identifiable Danish surnames in the region’s telephone directories (Hansen, Clausen, Jacobsen, Jensen, Petersen, etc.). Since 1864, the German language has prevailed in the town.

Additionally, many of them were swayed in the plebiscite of 1920 to vote for Germany by the threats of employers, especially at the largest workplaces in Flensburg—the naval base, shipyards, railway yards, paper mill, glass factory, rum distillery and breweries that production and many jobs would be moved to Germany proper if Flensburg were to be allotted to Denmark.

It was a decision many would come to rue, especially the tiny Jewish population. Most Jews in the border area lived in the city of Flensburg. By and large, this was a young community, unfamiliar with previous Danish rule (from the Middle Ages until 1864 when the areas of Schleswig and Holstein were lost to Prussia), of no more than 120 individuals in 1933. Most were Reform minded, favored assimilation and non-Zionist. Very few Jews lived in the Northern part of Schleswig which was predominantly rural and that had been returned to Denmark in 1920.

Older and larger Jewish communities were found in South Schleswig in the university town of Kiel, Altona (a suburb of Hamburg) and Friedrichstadt that had the only synagogue in the region. They had historically identified with the German majority.

By 1914, the adoption of Marxism made many workers in Schleswig who still identified with their Danish heritage doubly “suspicious” elements (potential Danish sympathizers and anti-imperialists opposed to a war of aggrandizement or colonial expansion). Even before the war, the German Social-Democratic Party had on occasion argued for a policy of “reconciliation” between German and Danish workers.

Their close proximity to Denmark and cross border contacts made many workers who had voted for Germany in the 1920 plebiscite realize how far the working class had progressed economically and socially in Denmark under a system opposed to militarism, as well as the fostering of humanitarian values and the spread of adult education on a massive scale. The progress made in Denmark during the inter-war years resulted in higher living and educational standards for the working class. Much of the pro-German vote in South Schleswig in 1920 had been due to the mistaken belief that these very objectives would be more easily realized in Germany.

In South Schleswig, the Danish-minded minority community organized cultural activity promoted to increase knowledge of Danish, establish free libraries, develop youth and scout movements, promote sports, encourage education, and to provide credit facilities to protect Danish-owned farms and offer church and welfare services for the minority community. A difficult problem between the minority and the local government which worsened under the Nazis was the fact that a majority of supporters of the Danish Minority Organization in the inter-war period belonged to Slesvigske Forening (SF) and were workers sympathetic to or former members of the Social-Democratic Party.

A clear majority of the votes cast for the Danish list were to be found in the working class districts of Flensburg leading to charges that “subversive Marxist elements were hiding behind a mask of an ethnic community.” Quite a few of these individuals were indeed reluctant to bear the economic burdens imposed by membership in the official minority organization and the social ostracism they would have to endure as “traitors” from their German comrades. Although the rank and file of the Danish minority organization came from a Socialist background, the political work was often led by individuals who had a conservative, Christian-Democratic and even had anti-socialist background.

When a German-dominated European organization of national minorities proposed a conference in Bern Switzerland in 1933, the choice of Jacob Kronika as the Danish “observer” was sharply opposed and considered an “unfriendly act.” Kronika had been editor of the German language newspaper “Der Schleswiger” and Germans considered this totally inappropriate for a spokesman of the Danish minority to have edited a propaganda organ to “win souls” from the German majority in South Schleswig. The German-dominated congress was so biased that no Jewish groups saw fit to send representatives and even the Swiss press characterized the congress as a pro-German charade.

Nazi policy regarding national minorities was contradictory in spite of their fervent nationalism and support for an irredentist policy to reclaim the areas lost in World War I. Although the local Schleswig-Holstein Nazi Party assumed that this meant a return to the Kongeåen—i.e. a restoration of the pre-war river boundary with Denmark. The German Foreign Ministry and various national Nazi Party spokesmen were careful to omit North Schleswig in their comments on future boundary revisions. Moreover, Hitler made several public speeches, most notably on May 17, 1933, in which he clearly defined Nazi attitudes towards the nationality question as being based on free will and these remarks were given prominence in the Nazi newspaper “Völkische Beobachter.”

Of course, this policy did not apply towards the Jews who were automatically to be excluded from German citizenship and defined by “race and blood.” Expressions of friendship towards Denmark as part of a friendly Nordic community of nations were made in German propaganda literature, but revisionist circles in Schleswig-Holstein launched a new campaign in the Spring of 1933 attacking the 1920 boundary, making it clear to the Danish community that the new regime posed a dire threat.

One of the first casualties of the new policy was the close alliance in the Reichstag between the Danish and Polish minority communities whose representatives had worked in harmony. A protest over a new electoral law promulgating a minimum of 60,000 signatures to qualify for participation in a national election split the Danish minority organization’s leadership which felt that too close an identification with the Polish minority party might rebound to their detriment. German opposition to the boundary with Poland was intense and the Danish Foreign ministry through their consul in Flensburg made it known that it would be unwise to link the Danish and Polish communities in the public mind.

For some however, this was a clear sign of opportunism and disloyalty since the officially recognized Polish minority community was more than ten times larger and had provided the backbone for the other much smaller minorities. Nevertheless, an important consideration was to stress that Danish minded Slesvigers believed in the principal of self-determination rather than the grandiose claims of both Germans and Poles who stressed “blood, language and soil.”

In 1936, a book entitled Dansk Grænselære (Danish Border Lesson) by a young teacher training college student, Claus Eskildsen, looked at the border conflict and national dispute in Schleswig over the generations. Eskildsen explained how the 1920 border dividing Schleswig into North and South between Denmark and Germany respectively had utilized self-determination on the basis of a freely held plebiscite as the fairest method of leaving behind the smallest national minorities.

Then, as a kind of “Devil’s Advocate,” he took the Nazi arguments of “Blood and Soil” and applied them to Schleswig. By examining a host of characteristics which were handed down through inheritance and had left their physical mark on the landscape or in the “popular sub-conscious” of the native population, Eskildsen demonstrated that South Schleswig clearly revealed its origin as part of “Danish folk territory.”

This could be demonstrated by the many elements of folk culture such as place names, family names, the layout of farmsteads and the names of streets according to the compass, church architecture, the house types in both town and country, idiomatic folk expressions that were literal translations from Danish to German, nursery rhymes, social mores, humor, superstitions, and even the type of wooden shoes preferred by farmers. This territory had, however, been subject to generations of German influence that had laid down a veneer of German acculturation (primarily language) but had left the old Schleswig folk character still in tune with its close Danish and Nordic antecedents.

Eskildsen’s real aim was to show how the concept of descent was unworkable and subject to conflicting views of history in contrast to the right of the individual to define himself according to the liberal principle of self-determination. He questioned how the Jews, imbued with German culture, could be excluded from the German nation while many volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) in America, Russia, Siberia and the Crimea had lost touch with their German roots, but pro-Nazi organizations in the 1930s continually appealed o them not to forget their German roots.

Shortly after the Nazis assumed power, discussions within the Ministry of the Interior led to proposals of a new citizenship law that would distinguish between formal “state citizenship” and a soon to be created “participatory citizenship” that could only be acquired through service to the state in such Nazi organizations as the NSDAP, SA, SS, and “Deutsche Arbeitsfront” (DAF) —a Nazi run union and would by definition exclude non-Germans. Severe measures had already been taken to eliminate Jews from all positions of importance and curtail their rights as German citizens under special legislation.

Attempts by the Danish minority organization to clarify this matter with the Ministry of the Interior received only answers indicating the necessity of distinguishing “Aryans” from “non-Aryans” in the determination of what was called “Reichsangehörigkeit” (belonging to the state). The constant threat of deprivation of their rights as German citizens hung over the Danish minority throughout the Nazi regime.

The only way for the Danish community to react was an editorial in the Danish language newspaper Flensborg Avis warning of the possible consequences of such an action upon ethnic German minorities in other countries. One ironic consequence of the Nazi racist ideology to prove their “Aryan (i.e. non-Jewish) ancestry” was the rediscovery of many Schleswigers that the marriage or baptismal certificates of their grandparents or great grandparents were in Danish or that family memorabilia such as diaries and letters revealed how in previous generations some individuals felt that their need to reluctantly learn German and imitate the Germans to fully integrate within German society were impositions.

The ability of the organized Danish minority community in South Schleswig to stand steadfast against the Nazi juggernaut and maintain its own cultural life, schools, libraries, welfare assistance and the only non-Nazi newspaper in Germany from 1933-45 was due to their courage and tenacity in the face of constant harassment as well as official German government policy. This policy made necessary the formal respect of commitments based on the reciprocity of the Danish government toward the German-minded minority in North Schleswig. An unintended consequence was that a tiny Jewish community in Flensburg, the major city of North Schleswig and only a few kilometers from the Danish border was able to take heart and prepare and organize for emigration or flight to Palestine or Denmark.

Aware of their tenuous position walking a tightrope, the Danish minority could not openly express the opposition of the overwhelming majority of its members to the regime’s anti-Semitic policies. The editorial line of Flensborg Avis remained as it had been under the Weimar Republic that it did “not interfere in internal German matters.” The paper went further in asserting that it aimed to serve as a bridge between Germany and Denmark, a view which the editors felt even more essential after the Nazis came to power and in spite of frequent criticism from the press and left-wing parties in Denmark. No one however, of any standing in the SF or Flensborg Avis openly or “behind closed doors” approved of the Nazi Party’s race laws, boycott of Jewish shops, anti-miscegenation laws, exclusion of Jews from public life, and deprivation of all civil rights culminating in the mass violence on “Kristallnacht” (Night of the Broken Glass) in 1938, by which time all Jews had left Flensburg.

It must be remembered that although the Nazis were the largest party in Germany on the eve of their assumption of power, the combined electoral strength of the Social Democrat and Communist parties in many areas was greater. This was true in Schleswig-Holstein where the Nazi Party had won overwhelming support from the rural population and many small farmers threatened with bankruptcy while the Social Democrats and Communists were strong in the larger towns (Kiel, Schleswig and Husum) and strongest of all in Flensburg where their combined strength and that of the Danish minority presented the Nazis with more of an obstacle than elsewhere to their usual smooth sailing over potential opposition.

A few local Jews were department store owners and shopkeepers with a tradition of excellent relations with the Danish minority. One of them, Herr Rath, was a faithful advertiser in Flensborg Avis and after being forced to leave Flensburg in 1935, expressed appreciation in a paid public notice appearing in the newspaper, thanking the community for its excellent treatment of him and his business. A Nazi sponsored anti-Jewish boycott in Flensburg in April, 1933 ended with little effect as the Jewish shopkeepers retained almost all their customers (from both the Danish and German communities) who were quite unsympathetic to Nazi appeals to boycott Jewish owned shops that offered them credit at a time when few others were willing to do so.

During the blockade of Jewish owned shops patrolled by uniformed S.A. guards carrying signs with cartoons of Jewish stereotypes denouncing “Germans who buy at Jewish shops are Traitors,” an unruly crowd of Flensborgers broke through the picket line to carry on doing business, a sensational news item carried only in Flensborg Avis, which gave it coverage. It is unlikely that any similar event occurred throughout Nazi Germany. Needless to say, the rival German majority owned newspaper, Flensburger Nachtrichten downplayed the incident and enthusiastically supported the boycott.

This little known but remarkable incident, unparalleled elsewhere in Nazi Germany showed how ordinary citizens could spontaneously oppose their rigid government’s official “boycott” of Jewish merchants in 1933 right after the Nazi assumption of power, and thus take a stand against the preposterous claims of official anti-Semitism. The incident, while on a much smaller scale than the highly publicized action taken in October 1943, ferrying thousands of Danish Jews in occupied Denmark to safety in Sweden, the later action was undertaken by many individuals from all walks of life and with the cooperation of numerous authorities in Sweden, Denmark and even among sympathetic German occupation officials.

This little known but remarkable incident, unparalleled elsewhere in Nazi Germany showed how ordinary citizens could spontaneously oppose their rigid government’s official “boycott” of Jewish merchants in 1933 right after the Nazi assumption of power, and thus take a stand against the preposterous claims of official anti-Semitism. The incident, while on a much smaller scale than the highly publicized action taken in October 1943, ferrying thousands of Danish Jews in occupied Denmark to safety in Sweden, the later action was undertaken by many individuals from all walks of life and with the cooperation of numerous authorities in Sweden, Denmark and even among sympathetic German occupation officials.

Aware of their tenuous position walking a tightrope, the Danish ethnic minority in the border province of Schleswig-Holstein could not openly express the opposition of the overwhelming majority of its members to the regime’s anti-Semitic policies.

The Flensborg Avis newspaper asserted that it aimed only to serve as a bridge between Germany and Denmark, a view which the editors felt even more essential after the Nazis came to power. No one however, of any standing in the Danish minority community or Flensborg Avis openly or “behind closed doors” approved of the Nazi Party’s race laws, boycott of Jewish shops, anti-miscegenation laws, exclusion of Jews from public life, and deprivation of all civil rights culminating in the mass violence on Kristallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass) in 1938.

Only by maintaining our moral compass and remembering and teaching those values and traditions that have been an inspiration throughout our history can we resist the present threats to our civilization approved of the race laws, boycott of Jewish shops, anti-miscegenation laws, exclusion of Jews from public life, and deprivation of all civil rights culminating in the mass violence on Kristallnacht.

From 1930 to 1938, Jews in Flensburg made use of a rented room for social events and meetings in the building of the Danish Community Center. Although sympathetic, there were clearly “limits” beyond which the Danish community could not openly express offers of assistance. Requests by Jewish parents whose children had been expelled from the German public school system were refused permission to transfer them to the Danish minority school

It must be also be borne in mind that the Danish government and its representative at the Danish consulate in Flensburg had warned the leadership of the Danish minority community and Flensborg Avis not to openly antagonize the Nazi regime or express sympathy on a community-wide level for Jews, Social-Democrats and Communists who had been forced out of public positions or had fled to Denmark.

This became even more acute after the Nazi prohibition against Flensborg Avis’s German language daily supplement, “Der Schleswiger,” as a result of accusations that the paper had been openly circulated among groups of “disgruntled communist workers in Hamburg’s harbor” who then had distributed it to “unscrupulous elements” and bookshops throughout Germany representing the anti-Nazi “Confessional Church” (led by the Reverend Martin Niemoeller until his arrest together with more than 800 pastors in July, 1937). The Danish minority community in South Schleswig had thus been branded as an ally of the regime’s opponents by some local Nazi politicians and revisionist circles anxious to recover North Schleswig. With the accusation of aid to Communists, Social-Democrats and the Christian opposition hanging over their heads, it is understandable that the Danish Minority Community could not risk further charges of open collaboration with the Jews.

Good relations formed with local Danish-minded farmers were later utilized in helping German-Jewish teenagers reach Denmark and carry on their agricultural training in 1939-40. Most of these boys and girls either reached Palestine (possible by traveling through Russia and Turkey until the German invasion of the USSR in June, 1941) or else fled to Sweden along with almost the entire Danish Jewish community in 1943. Alexander Wolff, the owner of Jägerslust made his estate available for the Zionist training program, managed to emigrate to the United States. From 1934 to 1938, a “HeHalutz,” (The Pioneer) Socialist-Zionist training farm operated in Jägerslust. Wolff later received compensation and a monthly pension after the war from the Federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, an invited guest of the Flensburg City Hall in 1966 and interviewed by Flensborg Avis.

His personal story and the farm that became a Zionist training farm is also a remarkable part of the sage. Established in 1857, Gut Jägerslust was acquired by Georg Nathan Wolff, a factory owner from Berlin, in 1906. His son Alexander, after three years of voluntary service in World War took over ownership and management of the estate in 1917 after his father’s death. Although he had previously been a German patriot and not especially religious, the new Nazi antisemitism resulted in the Wolffs turning to Judaism. He converted the estate into a teaching establishment of the “HeHalutz” Zionist youth organization, which prepared young Jews for a life of work in Palestine.

In the period from the fall of 1934 to the violent end of the Jägerslust emigration training center, around 100 men and women took part in the Hachshara (training farm) here. The names of 75 of them are known so far, 47 men and 28 women. At least 47 in this group survived the Nazi persecution. Most of them—31—made Aliyah and went to Palestine; five found refuge in the United States.

The attack by Nazi troops in the Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938) ended this interlude. The estate was destroyed by SA troops and everyone was arrested. Alexander Wolff was beaten and driven across the German-Danish border. His wife Irma found temporary refuge in the Danish old people’s home “Hjemmet.” Later, she fled to Berlin with her mother Käthe and sister Lilly. She and other inhabitants of Jägerslust were murdered in concentration camps.

The ability of the South Schleswig Danes to withstand constant harassment was a product of their ethnic pride and tenacious Christian or Socialist values. It was also made possible by official German government policy that, at times, contradicted rabid local Nazi Party members intent on recovering “Lost North Schleswig” as an irredenta. Hitler was anxious not to offend public opinion throughout Scandinavia by putting undue pressure on Denmark. His foreign policy was based on the reciprocity of the Danish government toward the German-minded minority in North Schleswig.

The unintended effect was that the local Jews had before them an inspiring example of their proud Danish neighbors who refused to bow to Nazi power and submerge their ethnic identity and strong Socialist or Christian values. The challenge of today is that we are in danger of becoming totally absorbed by the problems of the moment. Only by maintaining our moral compass and remembering and teaching those values and traditions that have been an inspiration throughout our history can we resist the present threats to our civilization from extreme religious or ethnic exclusivism and intolerance.

Table of Contents

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast