Research in a Far Away Time and Place

by Norman Simms (April 2018)

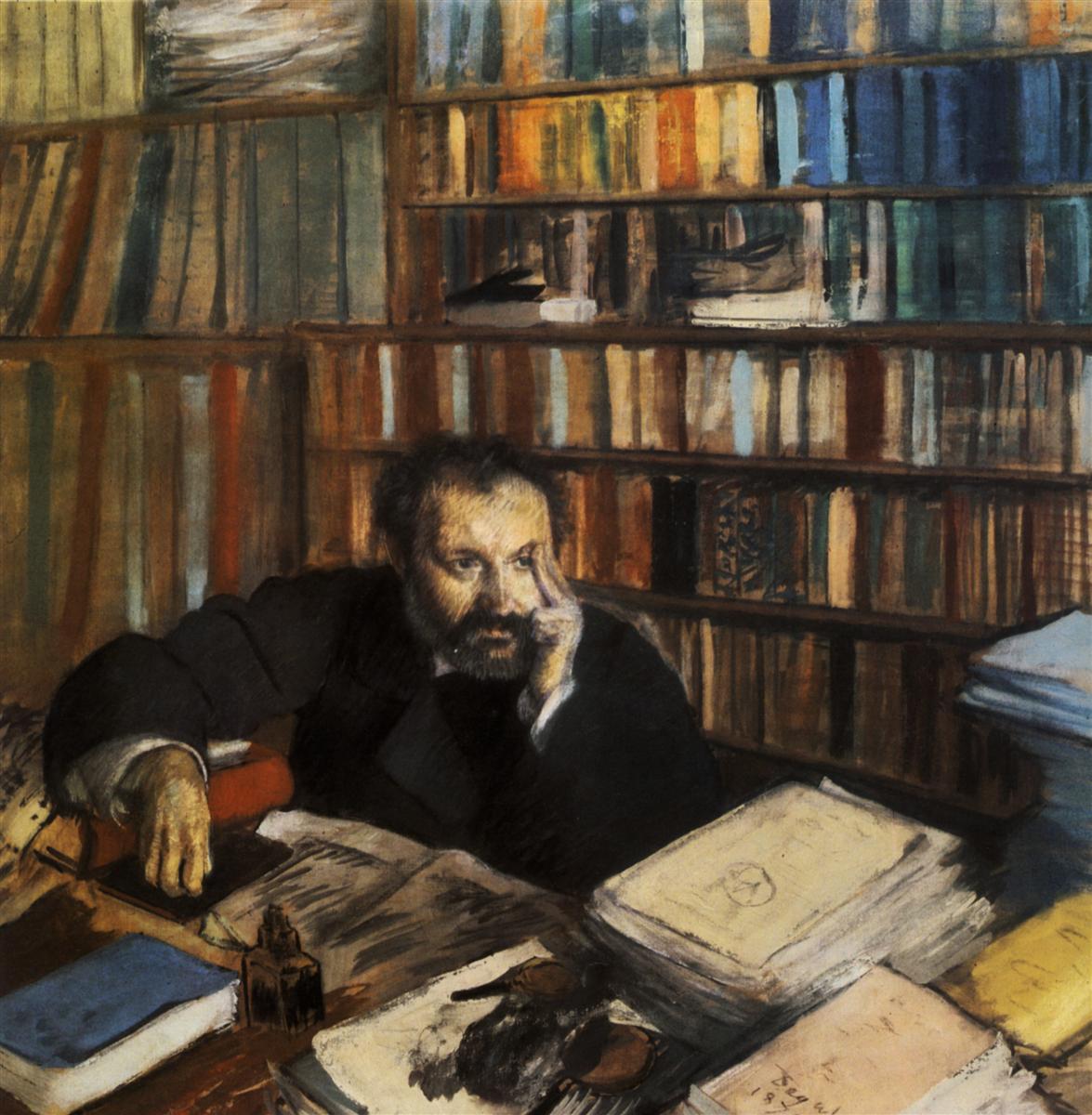

Edmond Duranty, Edgar Degas, 1879

or a book I am writing with a colleague on a very sensitive subject (children who kill children in terrorist attacks), I have been forced to go back to many authors I read forty or fifty years ago, at least. The subject requires a re-thinking and a re-synthesizing of ideas that have been at the very heart of all my teaching and writing. Not only have the main paradigms for scholarship changed in that half century, but the names of the people whom I once considered my essential sources have seemed to disappear from current studies. I owe it to those authors, colleagues, friends and part of the earlier Zeitgeist: to stave off cultural amnesia.

or a book I am writing with a colleague on a very sensitive subject (children who kill children in terrorist attacks), I have been forced to go back to many authors I read forty or fifty years ago, at least. The subject requires a re-thinking and a re-synthesizing of ideas that have been at the very heart of all my teaching and writing. Not only have the main paradigms for scholarship changed in that half century, but the names of the people whom I once considered my essential sources have seemed to disappear from current studies. I owe it to those authors, colleagues, friends and part of the earlier Zeitgeist: to stave off cultural amnesia.

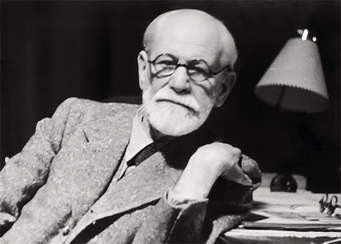

Discovery of the Unconscious

My first hero: Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

What has happened is that the ideas of the author’s I’ve read have been assimilated deep within myself, and merged with one another. A few authors and their ideas had been blanked out, and over the past few months, as the books appear again on my desk and I read through them, they shock me because they contain basic ideas, even phrases and sentences I have been using throughout my scholarly career without remembering where they came from. Thus, for instance, when I re-read Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams several things happen. One is that the arguments and the case studies seem familiar, but another is that what was first written in 1900 and then edited several times, seem weak and unconvincing. It now matters to me how Freud formed his insights, what the context for his arguments were, and where I can take the earlier studies which the great psychoanalyst’s controversial oeuvre has tended to block out. In my own status as an old man, too, I no longer have to look up to him as an unquestioned elder, but can see him at various stages usually much younger than I am now.

As retirement loomed, it seemed time to winnow out my book collection, especially on topics I had not lectured on for more than forty years and did not seem likely to be the subject of any new books to be written. There were also piles of review copies no longer of interest. Some of these old tomes were left in the hall with an invitation to students to take what they wanted gratis; no one seems to want them and I cannot bring myself to dump them, especially because many cannot be found elsewhere in New Zealand—and certainly not as clusters of related titles. This is mostly true with the box-loads of Judaica in Hebrew and Yiddish. Yet, in order to refresh my mind and check on specific citations for the new book, certain books had to be re-read and done so carefully.

Books about Books and People without Books

Books spill out of the shelves on to the desk and the floor

Even before retirement I realized that there was no good research library nearby to draw on, although friendly interloan librarians in Hamilton have done their utmost on my behalf. They have tracked down obscure old journals, museum exhibition catalogues from bygone ages and rare (though not expensive) titles of once popular titles a hundred or so years ago. They have been stymied by the increased restrictions on what can be sent from overseas. Multi-volume books, extra-large tomes and delicate early editions, as well as rare books are usually beyond our reach geographically and financially (because of special extra charges).

Rare books, of course, will not be mailed half-way round the world, although it has surprised me to receive carefully packed yellowed and crumbling pages which I have then slowly photocopied for my private research. Sometimes a tome has arrived published more than a hundred years ago, duly catalogued at some small public library in Canada or America, and clearly never let out on loan. In some of these, though, I have found the names of some early owner whose name can be looked up to be a local journalist of some ephemeral fame and who later donated his copy to the library or whose executors did the job on his or her behalf. Children are notorious for not recognizing the worth of a parent’s intellectual interests or have any knowledge of their special interests. Sometimes too handwritten annotation appear scribbled on the margins and fly-papers of the book and these have proved enlightening contemporary reactions to what is in the volume, highly personal rather than professional reactions, and yet rather eccentric and cryptic, such as lists of ciphers which are probably page numbers but which don’t seem to yield any pattern of names of places, events or ideas. Rarely, someone or other has tucked in a review cut from a newspaper, perhaps as a page-marker, perhaps as an aid to understanding. In used book shops, particularly of the old kind where back corners and low shelves have not been dusted or winnowed for generations, there are bus tickets or private letters, old photographs and recipes; useful sidelights and insights into the book culture of the era recently passed. In those queer little bookshops in small towns around the countryside I used to look through almanacs, books of sermons, trade manuals precisely for those serendipitous finds. Once in a while, as readers of my own books of twenty odd years ago, there were bizarre anecdotes and pieces of social history that I took as the subject for discussions on so-called naïve books (those by people technically literate but unfamiliar with the conventions of scholarship or professional editorial practices).

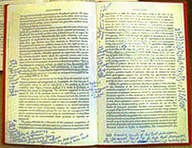

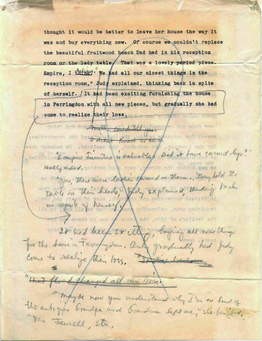

Printing, Writing and Thinking on the Page

Marginalia in the pages of a book.

Ironically, among the hundreds of ring-binders and file-boxes I have filled with handwritten notes, as well as photocopied articles and print-outs, many have faded, provided meals for silver fish, or succumbed to fly-blown splotches. It is also increasingly difficult to read my own scribble, and those yellowed and eaten-away pages. However, wonderful to tell, just a few words here and a phrase or two there, and I recall what was said, and what lies deep down in my intellect. Though it is impossible to cite such passages verbatim any more, there can be paraphrases and summaries of the argument, for which I feel no qualms or doubts.

Another strange phenomenon comes into focus during this period of massive re-reading of what are to me foundational books. The person who recommended or lent the book to me comes back to mind. The occasion of first perusal or discussion amplifies the sense of what is written on the page. This experience is quite rare, however. Most of the intellectual friends I have known during my lifetime I have never actually met. Our relationship has been through letters, at one time handwritten or typed on an old-fashioned pounding machine, but more recently by email. Since I have spent most of my life away from the United States where I was born 78 years ago, at the best the personal encounters have been infrequent and brief, usually during study-leave or attendance at some learned conference or other. Yet the more I think about influences on my way of thinking and the content of my thought, some of the most important insights and explanations have occurred during these very fleeting conversations.

A Time of Peace and Quiet

Lake Wyola near Shutesbury, Massachusetts.

Over the course of many years, I met with Robert Payson Creed at his university in Massachusetts or at some conference or other and, though he was close to twenty years my senior, we became close friends. He invited me to give guest lectures at the University of Massachusetts and also to be his guest in his house on shore of Lake Wyola in Shutesbury. We discussed oral literature, the theory of formulaic composition, and the archaeological evdience that provided the Old English and Nordic traditions with social and aesthetic contexts. Well-respected for his critical studies—and later his reproduction of the chanted recitation—on Beowulf, he taught me much. He listened patiently to what I said and, somehow without pulling rank, he corrected my errors and argued with my psychohistorical point of view, guided me toward greater understanding, and taught me how to find the scholarly backgrounds that were needed.

One summer, Bob invited my wife and me to house-sit for him. We went to Shutesbury for about six weeks. We decided to read through the collection of specialist books that made up Bob’s private library. Over the month and a half we spent there, taking long walks through the woods around the lake, swimming occasionally, and sleeping well at night when the temperatures dropped, I read my way through the hundreds of volumes already pre-selected in the areas of interest uppermost in my mind, with most of these volumes heavily annotated, or at least marked off with dates and arrows indicating when Creed found a point he wished to think about and come back to; on the pages Bob jousted with his sources.

This relationship with Bob Creed was the most sustained and the most continuous I have ever had.

Oral Minds and Formulaic Composition

Other encounters with ideas through personal meetings were less sustained, or bits of written letters or emails, or even dribs and drabs of memories. When I seek out these important ideas in my mind, I return to those moments of insight for the writing of the new book, and these often inchoate memories resonate with those moments of remembered people once known and not always met. Most of these encounters were brief and seemingly inauspicious. I doubt whether the person met in this way remembered the conversation, let alone me, or realized how significant the day was to my intellectual life.

Here is one instance. A few hours in the airport in Galveston, Texas, after a MLA conference, when I found myself in the lounge almost alone with the great and elderly scholar who had given the keynote address the evening before; we talked about his lecture, our mutual interest in Old and Middle English Literature, and about how and why we were both headed back to awkward destinations and so waiting for uncrowded connections. It was none other than Father Walter J. Ong, SJ, then President of the Modern Language Association. We discussed how the new ideas of formulaic composition found among the Slavic-speaking singers in the Balkans and used to understand the Homeric epics could also be applied to Beowulf and the fourteenth-century Alliterative Revival.

Another instance of a brief meeting that happened in Europe. At dinner after a formal seminar, sitting late together by chance other attendees having departed, I found myself chatting with someone whose name was all I knew about him, the older man (everyone was older than I in those days) and the young novice (myself). It was on a rare return to civilization from what even then seemed a self-imposed exile: the topics delved below the surface of clichés and jargon about the meaning of the oral-based personality versus the literacy of academic discourses. He was a person I was able to meet again shortly before he passed away. His generosity and patience are highlights in my life. He told me to read Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord, which I did, as well as all the books by himself I could find. The methodology was taking shape: when a book seemed important to me, I combed the footnotes for the primary sources, whether the comments were favourable or not, and followed them up; and then I looked for published reviews about authors who claimed to be influenced by the names now becoming familiar to me.

Then it was not only the scholarly works knitting themselves into interesting patterns of mutual reflection, but also the novels, plays, stories, poems and essays they mentioned. That led me to search out biographies and autobiographies of the fascinating characters who were, in my mind, creating a whole new world of knowledge. What they read, I wanted to read. What happened to shape their lives, I wanted to find out about. Not everything was possible, to be sure, but amazingly much was, and looking back over more than a half century of scholarship in this vein, I feel a little bit like a part of the cultural history that has spread itself out over my bookshelves, spilled out on to the desk, fallen to the floor, or lingered in my memory.

In the searches made in used book shops or in online sites, wherever it was possible, it was an original source, not a secondary comment that was sought after, and if that meant having to learn a new language, well so be it—or at least I tried. A reading knowledge, dictionary in hand, is not the same as a speaking fluency.

Research in Romania

A shepherd and his flock: Ballads of Miorita

My interests had shifted in the first decades from English Literature where I began as an undergraduate, to medieval culture that came into focus in graduate school, and then on, as chance would take me, to folklore. In search of “roots”, as one did back then, my wife and children came with me to Romania. A place was found for me as a visiting researcher in two institutes, the one for Southeast European Studies under the directorship of Alexandru Dutu, the other for Folklore and Dialect Studies where my mentor was Romulus Vulcanescu, and from them more informally—because many of the same directors and their assistants I was meeting knew each other and served on related editorial boards—to Comparative Literature and its journal Synthesis, which in that part of the world and under the direction of ideological trends, included popular and folk cultures. The supposedly universal legend and myth of national identity is in a ballad with thousands of variations found throughout the region: a shepherd and his mantic (speaking, prophesying) little ewe reveal the cosmic, trans-historical place and meaning of the people. When I started a little Romanian Studies newsletter I named it Miorita. The scholars, novelists and poets in Bucharest and other cities I visited were moved by the title and welcomed the opportunity to be read outside their own language zone—remember, this was in the early 1970s. Back at home, my colleagues were unimpressed, and ignored what went on in my office at the university.

After a few months in Bucharest and travelling to some other cities to meet “authors” and “editors”, a project was suggested for me: to start a journal dedicated to the History of Mentalities to be called Mentalities/Mentalités. As I came with little baggage—a stranger from a small isolated country on the other side of the world, untainted by a reputation to be protected or promoted—it would be my task to provide a neutral grounds for scholars from Eastern and Western lands to publish their work together. The journal and myself would be so unimportant that the project would not draw attention to itself by jealous rivals and censorious political overseers. As a consequence, over the years, when I could still travel, I started to meet many important people, very briefly, sometimes for a day, sometimes for an hour, to invite them to participate, to reassure them I was neither a spy or a rival, and that the journal and myself were unencumbered by institutional regulations. In time, of course, I realized that all this meant sacrificing advancement in academe—my home university did all it could to ignore what was being done silently in my office, no grants were offered or applied for, which left me to do what I wanted; with the compensation, such as it was, of doing the right thing. And, as it happily transpired, corresponding with scholars in the very thick of European culture, reading and processing the articles they submitted, each one verifying the validity of the other, and also receiving large numbers of top quality journals through exchange programmes and a lot of important books for distribution to reviewers. Many of these books, being too expensive to post on, remained with me to write the critical commentaries. After over thirty years of operating in this way, while I was never promoted or given recognition, I learned an awful lot, formally through the reading and writing that being an editor entailed, and informally from personal letters back and forth to the great men and women in the various fields that came to constitute our version of histoire de mentalités—such as cultural history, cultural anthropology, psychoanalyst, psychohistory, religious studies, iconography.

Sometimes on a study-leave I would meet a few of these scholars in Paris or Vienna, but usually not, and most of the people who I came to know, admire and work with I never met. In 1992, very soon after the revolution that toppled the Ceau?escus, I was back in Bucharest to see if any of my friends and relatives were still there. What a dreary city it was then, cold, dark, unfriendly, except for a handful of people who met me. Romulus Vulc?nescu twenty years on was retired, very weak, and lived alone in a small house crammed with books and papers. He came down the steps slowly to greet me, gave me a hug, and we chatted in a mixture of Romanian, French and English, only hinting at all the work he still wanted to do. I smiled. He gave me some offprints of papers published since I had last seen him, and then bid me farewell for the last time. And as for Alexandru Dutu, we met in his office at the Institute a couple of times. He was still tall, straight and dignified, but I could see things were not right: he too was twenty years older and not completely well. It was evident when I sat down to write up notes of our meeting later that he was no longer impeccably dressed, that he had a look of shabbiness about him, that time was taking its toll, and the new regime was not full of understanding for those who had never been completely in accord with the old ideas or with the new. That was one of the things he taught me quietly and often obliquely: not to fall into the trap of sentimentalizing peasant life and folklore and to be sceptical about the anti-rational ideologies that lay behind the all governments there—and elsewhere. I made up my mind to do something to help him afterwards. But life back home in New Zealand and especially at the university was harder than ever, and I could barely help my family or myself. More than ten years later the news reached me that both of these wise scholars had passed away

Origins of Consciousness, Language and Writing

Bone pendant from Glozel: mare and her foal.

There were other serendipitous events that happened either in my brief visits to North America, Israel, Southeast Asia and Europe. Let me tell you about one of the most important. During a one-term visiting lectureship at the Université de Pau, I received a note from someone near Vichy who said he had been told to contact me because of our mutual interest in psychohistory. Hardly had I stepped off the train in the station than Robert-Louis Liris asked if I would like to visit an archaeological site nearby. My answer was yes. Before going to his house, where my wife and I would be staying for a couple of nights as his guests, he drove off to Glozel. Who ever heard of this place? If Glozel did not change everything in my life and career, it sure came very close to doing so.

Ever since it was discovered in 1924 by a young peasant boy, Emile Fradin, out breaking in a new field in a valley near their home in the cluster of half dozen farm houses that form the hamlet of Glozel, the site has been the object of controversy. Not only what was found, but how it was found, who was there at the time, etc. I cannot think of prehistoric cave art or problems related to the origins of consciousness, language and symbols without measuring them by experiences in Glozel.

Unlike other prehistorical art which emphasizes the hunting of wild animals or their massive presence in vigorous activities, the imagery at Glozel depicts domestic scenes of maternal nurturance, domesticated creatures, ordinary humans at peace with one another. The stone and bone carvings, the outline drawing on clay tablets and pendants show a close relationship between the very markings that constitute the images and the uncanny shapes of something that looks like an alphabetic script; and when there are small clusters of “letters” that seem to be a word or a name, the same markings are repeated in a microscopic version only visible with a magnifying glass or, along with light filters, through photo-enlargements. Any theory about what it all means, or when it was made, buried, re-found and written over, and then collected and re-buried proves insufficient and adds to the controversy. Emile Fradin, although he has now passed away, but always in my mind’s eye, with his very enigmatic smile when asked about why he devoted his life to the strange things found in his grandfather’s field. He showed me the standing stones that had been cut down after 1918 by returning soldiers and, when the harvest was in, one could see the traces of a spiral path running down towards Glozel below. He mentioned old houses on the other side of the valley, and later that year, after I had gone—my last time to see Emile, my friends rented a small plane and flew over the area, discovering for the first time what had always been so elusive and contentious, the presence of a Gaulish settlement directly opposite the rows of underground chambers in which the various prehistoric objects had been gathered together and buried as a sort of sacred site or perhaps as some suggested a museum of their own all but forgotten history. The strange markings on the Neolithic objects Carbon-14 dating back 16,000 years and the clay tablets and statuary vases that date by thermoluminescence from between 2500 to 3200 years ago may have been added as ownership labels, memorial charms or social commentary.

The Way We Were Back Then

What Research Looked Like Before Computers

There are gaps in my history given here, just as there are always gaps in all history, and the best I can do for the moment is memorialize some of these breaks, lapses and empty places where more memories can be slotted later. It is also difficult for me to make formal statements on the changes to the way I think about the world, culture, the mind and the origins of consciousness, since very little of these influences are recorded in published or even private documents. Someday, given the right conditions, there will be other disclosures of people and places that shaped my life.

For me, just to have spent a few hours or minutes in certain places made a great difference. Thus passing through a city in Europe on the way to some other place meant I could do no more than quickly cross through a town square, walk hastily in and out of a cathedral, or just look out the window of a railway carriage at the buildings and the people. Such glimpses were enough to give me a sense of proportion in regard to how civil and ritual dramas were performed, to see the construction of historical change in the strata-like arrangement of different styles of architecture and the relationship of a townscape to the hills, rivers, plains and seashore associated with it: things that one may read about in books, but do not make sense except in actual witnessing. Once such places, like the people fleetingly met with, enter my memory, they also become part of what I am interested in and loyal to, even if it means, as it often did, disappointing my superiors and ruining my chances for professional advancement. Texts, pictures and rituals remain for me an interrelated palimpsest, a Talmudic like sea of commentary on commentary, a memory of dreams long forgotten. People I met constitute the living community of knowledge and scholarship that means more than anything else.

__________________________________

Norman Simms taught in New Zealand for more than forty years at the University of Waikato, with stints at the Nouvelle Sorbonne in Paris and Ben-Gurion University in Israel. He founded the interdisciplinary journal Mentalities/Mentalités in the early 1970s and saw it through nearly thirty years. Since retirement, he has published three books on Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus and a two-volume study of Jewish intellectuals and artists in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Western Europe, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise; Dust and Ashes, Comedians and Catastrophes, Volume I, and his newest book, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise: Dust and Ashes, Falling Out of Place and Into History, Volume II. Several further manuscripts in the same vein are currently being completed. Along with Nancy Hartvelt Kobrin, he is preparing a psychohistorical examination of why children terrorists kill other children.

More by Norman Simms here.

Please help support New English Review.