Rock Star at La Scala

by DC Diamondopolous (October 2023)

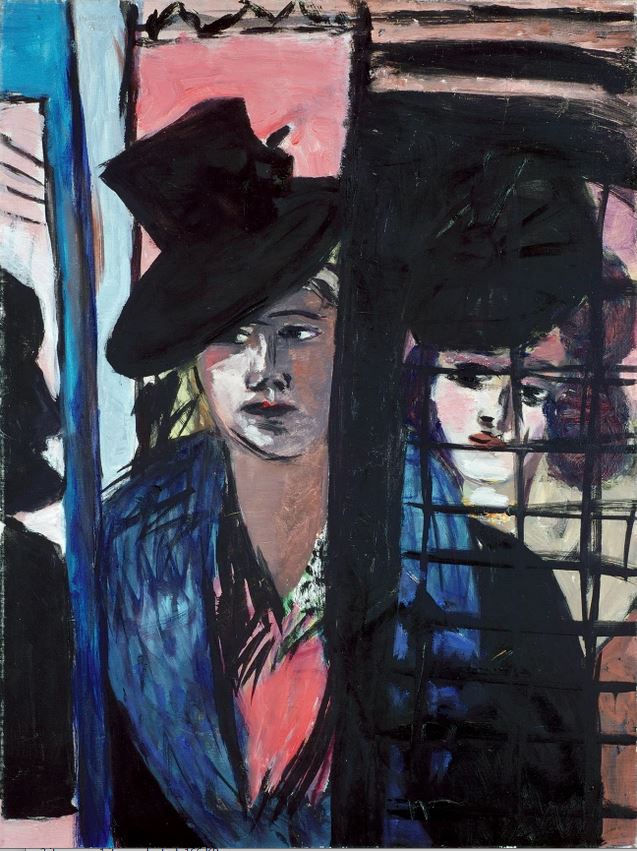

Zwei Frauen (in Glastür), Max Beckmann, 1940

Paparazzi elbowed their way past CNN talking heads as media from around the world made camp on the plaza. Fans, young and old, T-shirt vendors, street singers, mime artists, and pickpockets crowded La Scala Square, and the Piazza del Duomo. Helicopters circled, the chop-chop mixed with the thumping rock of the jumbo-screen speakers mounted in the courtyard. Pigeons lined the roof of the galleria. Others landed on statues and lampposts.

By late afternoon, as a cool summer mist shrouded the square, all of Milan had turned out to witness the unthinkable. Opera aficionados called it sacrilegious. For the first time since the house opened in 1778, a rock artist was to perform on the hallowed stage of La Scala.

***

Tonight’s performance would be my greatest moment, a rock show for the ages and a disappearing act. My life as Bel Shannon would end. A new journey awaited me. It would begin with a red-eye flight out of Rome.

Jasper Owen, my manager, sat beside me in the limousine. Across the aisle, Mavis, my assistant, watched Jasper with her lips pursed. Next to Mavis, Soner, my personal bodyguard, hunched forward scrolling on his phone.

Jasper’s cologne and Mavis’s perfume collided, an extension over who held the most power, who could outdo the other. The sweet, musky smell was as suffocating as their need to be irreplaceable—to me, the rock star, the illusionist.

Through the tinted window of the limo, I saw myself on the jumbo-screen. It was a replay of the HBO special at the Royal Albert Hall. Above the Jumbovision, on the rooftops of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele ll, Italian soldiers scanned the plaza. Tens of thousands of people had turned out to see me.

A fan broke through the barricade and threw herself on the hood of the car. She pressed her face to the windshield and yelled, “I love you, Bel.” Police yanked the girl away.

“Jesus. Here we go,” Jasper said.

“You have my kicks?” I asked Mavis.

“Here girl,” she said, handing me the tennis shoes, “You’re gonna need them.”

“I don’t like it,” Jasper said. “Sweeping the front of the theatre for bombs. I’m sure it’s been cleared. They just want a spectacle with you running across the courtyard.”

“Darlin’, since when don’t you like a spectacle?” I said, tying the Gucci sneakers and wishing my manager had stayed home.

It was a perfect prelude to what would follow. After all, I was a rock diva, a magician. Risk was my calling, and this was La Scala.

“I’m scared of those opera nuts, protesting like you’re something evil.” Mavis clicked her tongue and stuck the boots in a bag. “They’re worse than the fans.”

“Ah, they’re harmless.” I laughed, sounding relaxed, keeping the stress out of my voice.

We were once lovers. Mavis would be the hardest to leave. I didn’t want to be cruel, to abandon her and Jasper, my band and back-up singers, assistants and crew members, bodyguards.

“It’s not funny,” Jasper said.

“Lighten up, Darlin’. Nothing’s going to happen. Right, Soner?” I winked at the six-foot eight giant, an ex-basketball player from Turkey.

“You know it, Bel,” he said, and tucked his phone inside his coat pocket. “They’re here.”

Behind us was the SUV with my bodyguards and behind them a fleet of vehicles with my entourage.

For more than forty years, the media never let up. Hunted, chased for sport, the hounds snarling at my high-heeled boots, I once loved the adulation, until I forgot who I was and morphed into what others expected, running inside a sphere of my own making.

I pulled the brim of the fedora down over the wig. The hat brushed the rim of my Ray Bans. Strategically-placed tape held taut the skin at my temples and jawline. The black knee-length cape worn for dramatic effect kept me warm on this damp, cool day.

“Ready, Soner.”

“Time to rock and roll,” he said into his head-mic.

Soner opened the passenger door. Fans rushed the barricades. Police smacked them back. People screamed in Italian and English. Cheers and some boos went up around the piazza. Trumpets blared.

Stepping out of the car, I saw the opera devotees protesting with banners. Go home! You don’t belong here! I had paid ten million euros to coerce La Scala’s Board of Directors into letting me perform. I belonged here.

The bodyguards surrounded me. Ex-basketball players recruited by Soner, all were over six-feet-four. They wore dark suits and had a “don’t mess with me” look. I paid the best in the business, knew the names of their wives and children, and trusted these men with my life.

A roar went up from the square as I waved to the fans. People shouted, “Eccola, eccola Bel, ti amo!” On the jumbo-screen, I saw myself waving. The theatre held just over three thousand. I’d asked for the JumboTron in my contract so I could share the event with those who couldn’t buy tickets.

Surrounded by the Turks, I set the pace. The guards watched the people, with me peering between their shoulders, caged, viewing life within bars.

A boy held out a pen and a photo. “Wait.” I walked over, scrawled my signature on the 8 x 10 glossy, and let the teenager take a selfie with me.

I moved back into the shelter of my guards. They protected me as TV cameramen jostled for position and shoved microphones at me. I’d had nothing to do with the press since the turn of the century when they called me “embarrassingly old to be singing Let’s Funk All Night.”

Around that time tabloids plastered my haggard face below huge red block letters that screamed “Bel Shannon’s Death Imminent!”

We followed a path cordoned off by police and hurried along the Milan Cathedral. Fog drifted between the towering gothic arches and spires.

To perform at La Scala, I would make my grandmother’s dream come true. It was an offering to the woman who saved me from Saint Mary’s Home for Girls and gave me the gift of music. My grandmother had performed at all the great opera houses. She told me La Scala was her favorite.

The ballyhoo was panoramic. Photographers, news anchors, fanatics, and demonstrators ran alongside us. They shoved to get near while we raced across the courtyard. Confetti fell on my cape. It sprinkled on the heads and shoulders of the men shielding me. I knew how magic and illusion hypnotized a crowd. The belief that a superstar in a cloak, able to levitate, scale skyscrapers, and sail through the air with an electric guitar, was somehow greater than themselves. But I knew better. A woman who waited on tables and cared for her children was the real heroine.

People reached out their hands as if touching me would change their lives. “Bel, ti amo!” Who were they? Through the years, I wanted to talk with them, not at receptions before or after a concert, but in marketplaces, or on the street without the veil of celebrity.

Jasper wheezed, running beside me. He’d have a heart attack trying to control me. What would his life be like without Bel Shannon? I hoped he’d find happiness.

Mavis trailed Jasper. She’d become smothering, jealous of anyone who got near me. Their hatred of one another was like a snake, slinking and squeezing itself around my intestines while I tried to be fair to both.

We zigzagged around barriers and crossed the street to the entrance. The door opened.

A tall, light-haired man with a long face greeted us. “This way Madame.” I rushed in with my bodyguards. The vestibule, lined with marble pillars and statues, was elegant, its ceiling lofty, dripping with chandeliers. From this moment on, until my last bow, La Scala was home.

“I’m Mr. Ponti, the house manager. To the dressing room, Madam Shannon?”

“Yes. Thank you.”

“We at La Scala hope you enjoy your stay.”

“I’m sure I will.”

A year and a half prior, when meeting with the Board of Directors, I devised a scheme. Passing a floor plan of the building, I took out my phone and snapped a picture. I studied it. Most important were the exits.

The manager escorted me to the dressing rooms.

“Have a wonderful show, Madam,” he said with a slight bow, and opened the door. “If you need anything, call.” He gestured to a phone mounted on the wall below a CCTV monitor.

The cozy room had a vanity with a mirror. My trunk stood next to the clothes rack. In the center of the makeup table stood a bouquet of red roses. “The roses are beautiful. Thank the Board of Directors. But please take them. I’ll need the space.”

He handed me his card, picked up the flowers, and left.

When petitioning the Board, I told them about my grandmother, Naomi Shannon, who appeared at La Scala in the 1920s. Anyone familiar with classical music knew of her, the great concert pianist who broke through the ranks held by men. I told the Board it was my grandmother’s wish for me to perform here. The chairman met my petition with raised eyebrows and a half smile and said, “You’re not a classical musician, a ballerina, nor do you sing opera.” They refused my request.

Then when I offered them ten million euros, they decided to make an exception. I could have put on a circus act if I wanted.

Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi had been in this room. So had my grandmother, long before those divas. Now I, too, would be part of La Scala’s history.

“It’s batshit out there,” Jasper said, rushing into the room. “Let me get a picture of you, Bel.” He took out his phone. When I smiled, the tape holding back my skin at the jawlines went slack. The wig felt like a small dog on my head, the shades heavy on the bridge of my nose.

Mavis came in, wheezing, with my boots in a bag slung over her shoulder. “Next time I’m gonna get me a golf cart. You guys can run, but I’m in heels.” She kissed me on the cheek and whispered, “Baby, we made it to La Scala.”

Our love affair was long over, but Mavis still tried—pressing her huge breasts into my shoulder. She whispered, tickling my ear, “Girl, let me get a picture with you.”

I changed into my boots.

Soner watched from outside the door. “You want one too?” I held out my arm, the cape spread like a bat wing. “Darlin’, I want to see you smile for once.” He took a selfie of us.

“Give me a few minutes, Soner, and I’ll check out the theatre.”

With everyone gone, I went to the trunk, dialed the combination on the lock, and opened it. Styrofoam mannequin head, short dark wig, industrial tape, makeup kit, bobby pins for the wig cap, all as I had packed. The mini flashlight I stuck in my pants pocket. I closed the trunk and spun the dial.

In the corner of the room, I saw my reflection in the full-length mirror.

At the turn of the century, my career nosedived. Empty concert seats stuck out their cushioned tongues. Programmed to look young and sexy, I taped back my face, put on wigs, wore makeup and shades even indoors. And went into seclusion. How could I make fans love me again?

Rolling Stone Magazine called me a has-been. Suicide was an option. Then inspiration struck.

I studied with the brilliant illusionist, Igor Santini, and mastered the art of deception. My spellbinding performances packed stadiums. I became a resurrected sensation and the richest self-made woman in the world. But my music morphed into an accessory.

No matter how wealthy or renowned, I was still that child at Saint Mary’s Home for Girls, standing in line, waiting to be adopted but always passed over for the youngest and prettiest.

In the dressing room, I removed the sunglasses and examined my face in the mirror. The loose tape on the left side gave me a lopsided, abstract look. Plastic surgery had been too iffy. Too dangerous. Industrial tape achieved miraculous results. My face was a façade hiding the real Bel Shannon. Clothed, my body appeared the same as my twenty-year-old self, easy to deceive with posture and movement.

“Nana,” I whispered to the mirror. “Tonight is for you. You saved me from the despair of Saint Mary’s.”

Mother Superior had called me to her office. My six-year-old body trembled with fear. Was I going to be whipped? Did they find out about Ruthie and me?

Ruthie sang all the time. I wanted to know how she made those sounds come out of her mouth. One night, I had sneaked out of bed, tiptoed down the hall, and crossed into the colored girls’ quarters. “I want to sing like you,” I told her. We pulled the sheets over us and in whispers she taught me how to harmonize. In soft voices we sang Mary Had a Little Lamb and The Itsy-Bitsy Spider. Singing was my first taste of happiness.

Sister Marie led me through the halls.

“I’m a good girl.”

“Hush, Isabel,” the nun said, pinching my arm.

She led me into a sanctuary where an older woman with lace gloves raised the veil on her hat. “Hello Darlin’, I’m your grandmama. Call me Nana.” She winked. “It doesn’t sound so stuffy.”

What’s a grandmama, I wondered? When we rode away together in the back seat of a big car, Nana said, “My daughter was your mother. I’m sorry it took so long to find you.” That was the last time she mentioned the word mother.

Nana took me home to a mansion, but it was the music room where I lived and thrived.

On Sunday afternoons, Nana held concerts in the music hall where she and others played Grieg, Debussy, Gershwin, Ellington.

When I first heard rock and roll, I learned the guitar and wrote my own songs.

But so many years later, veering far from my music, magic and illusion robbed me of my voice. To rot was one thing. To continue to rot after I realized it was quite another.

I inspected the clothes rack and ran my fingers over the soft material of the gypsy blouse. My trademark the velvet purple cape would fall to the middle of my calves in elegant straight lines. My performance boots shone.

With all my belongings in place, I went into the hall.

“Ready?” Soner asked.

I whirled around, my black cape flaring as I vanished down the corridor.

***

After the band’s soundcheck, I walked center stage and gazed around the empty theatre. I breathed in the centuries of performances, hundreds of years of furs and fragrances, the stale smell of powerful rich men, and the sweat from the poor in the loggione.

Closing my eyes, I belted out two bars from It’s All About You. Too bad we had to use microphones, the acoustics were marvelous.

Soner and the bodyguards watched from the wings. Mavis sat in the front row, looking at her phone. In the back of the theatre, Jasper talked to Mr. Ponti. Along the aisles, my assistants, musicians, and back-up singers took pictures and wandered around the historic building.

I moved upstage to the escape hatch. Soner hurried over. “Stay here and don’t let anyone down,” I said, sliding back the door. “I’ll do this alone tonight.”

“But Bel? What if someone’s down there?”

“You serious? With all the security?”

I climbed down several steps and closed the trapdoor. The dank air caught in my throat. Coughing, I crouched on the stairs, removed my sunglasses, and tucked them under the fedora.

A string dangled. I tugged it. Light illuminated layers of grime that covered pipes running along the brick walls.

Nana’s steamer trunk stood by the steps, covered with travel stickers from The Grand Hotel in Stockholm, the Hotel Ambassador in Vienna, and other locations from around the world. Like an old friend, the trunk had traveled with me throughout my career. It was part of my grandmother, and it made my heart heavy to leave it behind.

I dialed the combination on the lock and opened the chest. On one side was the springboard and rocket booster. In another compartment, an identical shirt to the one hanging in the dressing room along with tissue, make-up remover, a mirror, street clothes, and a large tote bag. I unzipped the bag and checked inside.

Perfect. I shut the trunk, spun the dial, and yanked the light string.

Having memorized the floor plan, I knew the passageway. La Scala had one of the deepest stages in Italy. The first door I would pass would be the one that led offstage to the right wing. The second door opened to the back of the theatre where crews built sets and painted backdrops. My exit would take me to the rear of the opera house and a door that would open onto a narrow street.

My flashlight pierced the dark. In slow motion, I skimmed the light across the floor and ceiling, then side to side. The cellar was used as a storage space for dismantled sets, abandoned furniture, and props. Moisture trickled down walls, cobwebs as thick as angel hair hung between rafters.

My timing was crucial for me to arrive at Milano Centrale to catch the train to Rome. I’d practiced my change, over and over, and clocked it to thirty seconds. Adding that to the watch, I pressed the button and did a dry run.

As I advanced into the bowels of La Scala, rats scampered from under large hulking outlines covered in tarp. I hurried on, passing the second door on my left. The next would lead out the back of the building.

Just ahead of me were the stairs, with a shaving of light shimmering under the door at the top. I pressed the button on the watch—two minutes and seven seconds total—put the flashlight in my pocket, removed my hat, put on the shades, placed the fedora at a rakish angle, and climbed the steps.

No need to pick the lock, it had a deadbolt. When I turned the knob, the door swung wide from the outside causing me to stumble.

“Jasper.”

“Bel! What the hell are you doing here?”

“What are you doing here?”

“You went down the hatch alone.”

A light drizzle was falling. At both ends of the street, police patrolled, and barricades blocked the road. Jasper turned up the collar of his overcoat. The tremor in his right hand shook more than usual.

“Come stand in the doorway,” I said. “You’re getting wet.”

“Why’d you come out here?”

“I wanted fresh air.”

“Bel,” he said, shaking his head. “Don’t do anything foolish.”

“Why would I? You’re too uptight.”

“I’ll tell Ponti to put guards at every door.”

“The street’s already blocked.”

“Anyone going in or coming out will be checked. This building will be on lockdown while you’re in it.”

My future happiness depended on this door.

“Let me book you at the Olympia. Three million euros for one performance. Not even Vegas pays that. Come on, Bel. You could make back almost a third of your give-away here.”

“Let it go.”

“It was beneath you to pay them. You should have had me negotiate.”

“You didn’t see the contempt on their faces. It was the only way to get the gig.”

La Scala was the first time a contract had been signed without him. I no longer needed Jasper. My plan to disappear had been resolved as I scrawled my signature across the contract.

“But I should have been there.” He stepped out from under the doorway. “The French want an answer.”

“I’ll give you one by the end of the night.”

“Why not now?”

“Two or three hours won’t matter. You never told me why you were here.”

“Soner wouldn’t let me go into the basement. What are you really up to?”

“Relax Jasper. It’s been a long time since you’ve been on the road.”

The clouds hung low on the horizon. “Hope people on the piazza remembered umbrellas.” I stepped back inside. “See you onstage.” And I slammed the door shut.

***

Jasper sat on a Victorian loveseat in La Scala’s lobby, staring at the marble floor. The crystal chandeliers illuminated the busts of Verdi and Puccini. The vestibule, awash in golden light, didn’t brighten his mood. He glanced at his watch. Bel’s refusal to book concerts gave him panic attacks. What was she up to?

Her transformation began several years back, in Amsterdam, then a trip to India. When she came back, she closed her Facebook and Twitter accounts. Except for her phone and website, she shut down all electronics.

His agony over losing her made him leave his home in Palm Beach and fly to Milan. He tagged along like part of her entourage.

Why did she really go out the back door— “wanted fresh air” —a lie, like others.

She’d been his ticket to the high rollers, star-fuckers, anything he wanted. Decades passed, but not his obsession to control her. His persona was linked to Bel. Now he felt himself clutching the hem of her fame.

Information about her came from social media and the tabloids. Photos of Bel arriving at the San Fransisco Airport in her private jet dominated the Internet. No one knew why she was there, or how she dodged the media. What was her destination? Her mystery whipped up a mania, and the paparazzi preyed on her. If she blinked, Bel Shannon made headlines.

Without him she’d still be singing in blues joints. After her grandmother died, Bel ran away. She was seventeen and afraid she’d be taken back to St. Mary’s. He found her in Harrisburg, at the King Bees Juke Dive, pounding on a piano a righteous rendition of Rock Island Line.

“Hey, kid,” he had called her. “You’re good. Good enough to record.”

“Become rich and famous?” Bel had asked.

She was slender, taller than average, a striking beauty with eyes as dark as Pine Creek Gorge. But there were lots of good-looking girl singers. It was her voice, its husky quality, and the way she played the piano—he hadn’t heard anything like it since Memphis Slim. A cat handed her a guitar, and by God, she played that too—and the harp!

Jasper swiped the tassel on his Ferragamo moccasin. Like others, he had fallen in love with her. Her magnetism attracted both men and women. He protected her when lovers tried to blackmail her.

In the 1980s, she had big hair and padded shoulders. MTV played her videos 24/7. Her success advanced to the big screen with several hit movies.

All the while, it was he who made it happen. Not once had he thought of taking on another client, not even when she became a has-been. When she added magic to her shows, he made sure she had the best teachers and assistants. He’d sacrificed his whole damn life to Bel.

He had watched her do daredevil stunts, levitating over the Hollywood Bowl while playing a guitar, hanging upside down like a bat, then walking across the ceiling inside Carnegie Hall. God knows how many bones she’d broken. He rubbed his knees.

Humiliating as it was, he needed an ally. Jasper took out his phone and texted Mavis. “We need to talk. Meet me in the canteen.”

Mavis texted back, “I’m here. Eating a fine dish of pasta.” Of course, Mavis lived to eat. Twice divorced with three sons and several grandchildren, she’d been with Bel for over ten years. They’d been lovers and that really galled him.

With his hand on the railing, he lumbered up the stairs and walked inside the canteen.

Bel’s musicians, back-up singers, magic assistants, and techies clustered in groups, snacking and talking.

Mavis sat alone with a big plate of spaghetti and a glass of red wine. Attractive in her blue pant-suit with a low-cut top showing off her enormous cleavage—probably for Bel— was the woman Jasper loathed.

He grabbed a chair and sat down.

“It’s Bel.”

Mavis stabbed a meatball with her fork and continued to eat.

“She went down the escape hatch alone. Insisted on it, Soner said. I caught her going out the back door of the basement.”

Silverware and dishes clattered into bins.

“Told me some lie about wanting fresh air.”

Mavis twirled spaghetti on her fork and continued to eat.

Irritated by her cheeky attitude, Jasper asked, “Has she been talking to you?”

“This concert’s a big deal,” Mavis said, taking a sip of wine. “She’s nervous. So am I. All this bomb stuff would make anyone nuts.”

“I want to book her at the Olympia. Says she’ll think about it. She’s put me off for days. Has she said anything to you?”

Mavis pushed aside her plate.

“Never mentioned it.”

He glanced at the gray walls and tables. The canteen’s drab atmosphere added to his gloom.

“No upcoming tours. Nothing,” Jasper said. “She sold her home on the Rialto. The manor in St John’s Wood, and her favorite, the villa on Mykonos, are for sale too.”

“You talking tabloid trash or you know something for real?”

He hunched forward. “I saw the listings on the Internet.”

He watched the rise and fall of her chest, the grim set of her mouth. She didn’t fool him. Mavis was scared.

“That girl’s been a mystery for some time,” Mavis said.

“It’s like she’s tidying up loose ends.” Jasper scratched his goatee. “Tonight could be final.”

“As in?”

“Her last show. You know.”

He hesitated, letting Mavis visualize the ultimate showstopper.

“You’re talking nonsense. That’s too far over the top even for Bel.” Mavis grimaced and looked sideways at him. “She’s not depressed. It’s all that mediating and chanting. It’s turned her into a stranger.”

“She’s auctioned off her Warhols and Lichtensteins.”

“Where’d you hear that?”

“It’s around.”

“Rumors, hmph.” Mavis opened her handbag and took out her lipstick, then tossed it back. “I know that girl’s planning something. I have eyes too, you know. But not suicide. So you just shut your mouth about that. Why would she go out the back door if she wants to kill herself? Maybe she did need fresh air.”

Jasper noted the uneaten food, the furrowed brow, her unpainted lips.

“I know how you feel about her,” Jasper said.

“You don’t know shit. I know Bel better than anyone. I’ve seen that girl go through so many phases. You and I both know when it comes to her image and being on top, nothing stands in her way. Not those protesters, or bomb threats, nothing.”

“You know she’s up to something,” Jasper said. “Something big.”

“What do you want from me?”

“Your help.”

“That bad, huh?”

“Instead of being in the audience, let’s watch her from the wings. We’ll make sure she leaves the building with us.”

“She’s been acting funny,” Mavis said. “Faraway like.”

Jasper stood and said, “We have to watch Soner, too.”

***

Alone in the dressing room, I flung off my cape. Damn Jasper. Damn the bombers. It would have been perfect going out the back door. Even with the street blocked off no one would have bothered me. But not now with a guard posted.

There was shock in Jasper’s eyes when he swung open the door. Good thing for the shades, or he would have seen the horror in mine.

I threw my hat on the counter and took off the sunglasses.

Plan B? It would be the magic trick of a lifetime, more frightening than scaling the Shanghai Tower. It wasn’t just Jasper and Mavis, it would be my whole entourage, people I’d been close to. Could I be invisible to them? If I failed, not only would it be humiliating, I’d never be free. But the boldness of it, the daring, thrilled me.

From the open trunk, I took out the make-up remover, pulled off the tape, and cleaned my face. Staring at myself in the mirror without cosmetics and adhesive, I wondered — could I get away with it?

Without the Bel Shannon disguise, I had bought my farmhouse in the California mountains and shopped at the village market. The locals welcomed me as Jennifer Miller, offering tips on where to hike and the best places to go kayaking, and there was Denise.

The thought of being with Denise gave me courage. She loved me without knowing Bel Shannon, not like Marta, who broke my spirit.

My transformation began with Marta in Amsterdam. I had been playing a boogie-woogie on the harmonica when I saw her from the stage. The lovely woman sitting in the VIP section smiled up at me. I boogied down to the apron and blew the harp as cartoon notes circled around her head. She laughed and grabbed at the illusions. I was smitten. At the intermission, I asked Soner to give her a backstage pass to the reception.

At the gathering, I shook hands, chatted with royalty, politicians, and celebrities. I’d glance at the door, then greet the next person. I nibbled at the banquet table that was lush with fresh fruit, cheeses, and wine.

“How do you levitate?”

Startled, I turned to my guest, put my heart back in its place, and said, “It’s a secret.”

She answered in low voice, “I’ll keep it.”

“Even so.”

“Thank you for the pass.” She poured a glass of champagne, then swept her blonde hair off her shoulder.

“What’s your name?”

“Marta. Marta van der Berg.”

Within the hour, I brought Marta to my suite at the De L’Europe Amsterdam where we became lovers.

Marta was always on her phone, scrolling, texting, tweeting. “Who?” I had asked. “Facebook, and friends,” she said.

We took midnight walks in Vondelpark and drove to Bruges. I felt myself sliding, a helpless feeling, overwhelmed by the audacity of falling in love.

After ten days together, the limo driver took me—along with Soner and the bodyguards—to Rotterdam and my favorite antique store. While there, I bought Marta an Art Nouveau necklace made of emeralds and diamonds and planned to ask her to join me on tour.

That night, in the hotel room, I gave her the wrapped box.

Naked, Marta strode over, reached for the present, and opened it. “It’s gorgeous.” She turned. “Clasp it. Then make love to me.”

I pleasured Marta, running my hunger over her breasts; the curve of her belly, my tongue along the inside of her thighs.

I glanced up and saw her texting on her phone. Stunned, I grabbed it, read, “You’ll never guess who I’ve been fucking.” Devastated by the betrayal, I smashed the phone against the nightstand and marched to the French doors, opened them, and threw the phone into the Amstel River.

“You told me you loved me.”

Marta unclasped the necklace.

“Keep it,” I hissed. “Take your clothes and get the hell out.”

Alone, in the middle of the room, I sobbed until laughter drew me to the balcony. A boat cruised along the Amstel with men and women eating, drinking, making toasts. The simplicity of everyday life, a boat ride with friends, I hated them. Hated their happiness. Appalled by my jealousy and overcome with shame, I wandered into the suite pondering where I had gone wrong.

When Marta shut the door, it was more than a closing. It was an awakening. What happened in Amsterdam forced me to look within.

Nana would have been pleased with my La Scala scheme. My happiest memories had been when we picnicked along the Susquehanna River. Nature and its integrity. That’s the life to live, far away from illusions. My sophisticated grandmother, who behind closed doors smoked thin cigars, swore, and taught me to play poker, would have said, “Darlin’, it’s about time.”

***

I applied clear industrial tape along both sides of my jawline and pulled the loose skin back under my earlobes. With small pieces of tape on my temples, I dragged back the wrinkles around my eyes. Pancake make-up smoothed, and powdered hid the strips. My face painted, I fastened the dark wig with bobby pins then sang the scales.

Dressed in my performance clothes, I slipped on my royal purple cape and clasped it at the neck. For almost twenty years, the cape had made me feel dramatic and powerful, but it too was an illusion.

Flanked by Soner and the guards, I strode down the hall toward Mr. Ponti, who waited at the elevator. It descended to stage level and opened to a flurry of assistants. The theatre’s security personal scanned the seats and aisles.

Claire, my magic assistant, hurried over. “The 3D projector, ropes, risers, pyrotechnics,” she said, checking the list and adjusting her glasses. “It’s all ready. What about the rocket booster?” she asked, taking off my cape.

“I can handle it.”

Roadies jostled the grand piano onto the stage then set up the instruments. The band members and backup singers tested the microphones.

“Nervous, Bel?” Alvin, the bass player, asked.

“Yeah, darlin’, but you better not be.”

“Shaking in my boots. This is some kinda history you’re making.”

“Snap that baby with a whole lotta funk and you’ll be making your own.”

Mr. Ponti hurried down the aisle.

“We open the doors in five minutes, Madam Shannon.”

The stage manager ordered the proscenium and backdrop curtains lowered.

Soner and the bodyguards followed me past the set of Carmen. I dragged a stool into a corner, where I was surrounded by tall baroque chairs and secluded from people. The guards watched me from several feet away.

I closed my eyes. Worry and blame interfered with my concentration. Upon my decision to escape the world of rock and magic, I considered all it would affect—my band, assistants, the crew that toured with me, Jasper, and Mavis. All would feel deserted and betrayed. I had set up a trust fund for all my employees, hoping the money would assuage their anger, and my guilt for leaving.

I controlled my mind, transcended thought, and listened. Mavis will find her way, as will Jasper and everyone else. Be here now. Spontaneity is the brush of artistry.

***

I stood upstage behind the grand drape. I whirled the satin cloak like a lariat and let it slip to the floor in a majestic purple splash.

Everyone took their positions.

The band played a blistering intro to “Scare City.” The back-up singers wailed into the microphone, “Scare City, Scare City, scarcity no more.”

The house exploded in a frenzy, “Bel! Bel!”

I stood on the third stair of the trapdoor and attached the wireless mic and in-ear monitor. Claire handed me the Gibson.

The curtain rose to a screaming thunderclap. Lightning streaked across the house, the spotlight aimed on the purple pond lying on the stage.

The cape came alive with me underneath. Always more gentleman than lady, I took a deep Casanova bow. My love affair with the audience began.

I swung the guitar in front of me and let rip the riff from Addicted to Drama. Each string shot streaks of red, blue, yellow, green, orange, and purple.

The crowd stood in a unanimous roar.

Crossing to the apron, I accepted the adoration, with a smile and wet eyes. My open hands emitted green, white, and red streamers that mutated into small Italian flags. Applause and bravos went up in the house.

I smiled at the VIPs in the orchestra section, those beyond in the platea, the prima galleria, the seconda galleria, up to the leggione.

I concluded Addicted to Drama as my image faded in and out, then disappeared. The guitar, suspended in air, continued to play. People shouted in Italian and English, “Bel, come back!”

Beneath the stage, I removed my cape and took out the rocket booster while the band played the refrain to Watch Out Or You’ll End Up Where You’re Headed.

No one except Santini knew how to do the next feat. He’d taught me, warned me about precision, schooled me in the art of landing. I’d practiced Rocket Body for months, a risky act at any age but for my advanced years, illusionists called me insane.

The band stopped playing, then a drumroll. I slid open the trapdoor, moved away from the stairs, and stepped into the air-foot compressors with my arms pinned to my sides for a clean shot.

The soles of my boots were seared from the blast of propulsion. My body shot through the air, left a smoke trail, where I landed feet-first on the third tier. The audience gasped, went wild with applause. I sat on the cushioned rail, my boots dangling over the ledge — and my heart skipped, thankful I’d never perform Rocket Body again.

Clouds of smoke and gases lingered on stage. It hid my assistant as she closed the trapdoor.

In an aisle seat, a man in the fourth row interrupted my concentration. He groped under his chair and the one in front. Perhaps he’d lost his program. But then a patch of light made me wary. His phone.

I dismissed him as being rude and levitated above the heads of the patrons and landed back on stage at the grand piano. Striking the keys, I played, There Is Nothing To Worry About.

When the back-up singers wailed the refrain, Ever again, the rude man with dark, slicked-backed hair, a dead ringer for a Corleone hitman, stared up at the first tier and gave someone the thumbs up.

Did anyone else notice him? Jasper, Mavis, and Soner were watching from the wings. Perhaps it was nothing.

Alvin slapped a funky bass and sauntered over. We flirted while he strummed a steady groove.

I knocked over the bench, legs spread, back arched, and shouted the lyrics as my fingers ran the keys.

Charmed by the captivated audience, I hovered several feet above the piano while the keys continued to play.

Screams circled the hall. Panties, a pair of boxer shorts, and a bra landed on stage—I saw the price tags on them and laughed.

Distracted by a patch of light from the audience, I looked over. It was the man with the phone. He stared at it, then glanced over his shoulder. Was he an opera fanatic and about to set off a bomb?

I strolled to the proscenium and at the end of the chorus ad-libbed a scream so loud that he finally looked up.

In sync with my improv, the band stopped playing.

“You! Yes, you,” I said into the head-mic, gesturing to the possible terrorist. “Come up here.”

He slouched in his seat shaking his head.

“Darlin’ I’m not going to hurt you.”

The audience clapped.

“I’ll come up,” someone shouted.

“Grazie. But I want him.”

Wolf calls looped the hall.

The man put his phone in his back pocket and walked to the stairs. We shook hands.

I included the audience as I said, “What’s your name?”

“Lu, er,” he stammered. “Luciano Fognini.”

“Is my performance boring you?”

He shook his head. “No,” he said.

“Then why the obsession with your phone?”

The crowd laughed. His face reddened.

“This is the age of electronic addictions,” I said and held out my hand. “May I?”

“Cosa, er?”

“Your cellular.”

He reached in his back pocket. Not finding it, he searched all his pockets.

Triumphant, I held up his phone with a flourish for the audience. There was a shared intake of breath, laughter, then applause.

Luciano reached for it.

I snapped it away. “Play on.” The band and singers launched into a medley of my hits.

Luciano’s hand in mine, we walked over to Soner.

“Check it out. He has an accomplice in the balcony.” Two of my bodyguards stood on either side of Luciano. Mavis looked on. “Be careful. It could be programmed.”

“Uh, what?” Luciano asked.

Soner scanned the text messages, then took off the back of the phone and looked inside.

“Hey, cazzo. Fuck, mi dia, mio cell.”

Soner put it back together. “He’s in love. Wants to marry his girl. She’s sitting in the balcony.”

Embarrassed, feeling the blush on my face, I took the phone from Soner and said, “Make reservations for two at the Casa Lodi.” I held Luciano’s hand and brought him on stage.

“Our friend is in love. Go ahead, ask her.”

“Now?”

“Why not?”

“Di fronte, er, everyone?” he said.

“She’ll love it.”

“Sposami. Marry me, Tina,” Luciano shouted.

The audience cheered.

“Marry him,” a man bellowed, “so we can get on with the show.”

A young woman with long black hair rose from her seat. Tears ran down her face.

“Si, Luciano. I’ll marry you.”

Luciano blew her a kiss.

“Here. Keep it off during the performance,” I whispered and handed him his phone. “Dinner on me at Casa Lodi. And congratulations.”

***

Soaked in sweat, I disappeared into the basement.

From the top of the trunk, I grabbed the flashlight, opened the case, changed into the fresh gypsy blouse, and put on my cape.

Back on stage the band joined me.

“We’ll skip Cookin’ In My Casket. We’ll add it to the encore. If they want one.”

“Ah c’mon Bel, they’ll wanna to stay till it’s daylight,” Alvin said.

“Don’t assume. This has been a weird night. Now I’d like a few minutes alone.”

***

Mavis watched Bel meditate backstage. Her girl was planning something.

Over the years, she’d lost her sway with the rock legend. Their first big argument happened because of that damn tape she used on her face. Bel preferred giving pleasure, but when Mavis responded—eager and aroused—and tried to strip away the tape and peel off the wig, Bel jumped up and refused to have sex with her. Weeks passed before Mavis seduced her into bed.

Something happened in Amsterdam. Bel was back in her arms, but the pillow talk faded. Soon after, Bel left for India. She sent Mavis letters, writing about her devotion to mysticism and transcendental meditation, things that at first seemed like a phase. But when she came home filled with talk of the material world being a shadowy reflection of the spiritual, that God had both male and female aspects — Mavis balked. She clung to her Baptist beliefs and avoided religious conversations with Bel.

When the illusionist finished her meditation and opened her black-rimmed eyes, they glowed, her pale skin luminous. Mavis thought her a goddess.

“Baby, what’s going on? You’re putting nothing over on me.” She saw the flush beneath Bel’s rouge. Mavis drew close. “You’re not booking concerts. What’s this about selling your homes? And your art collections?” Frightened when Bel didn’t answer, Mavis said, “Jasper’s talking crazy. Like you killing yourself onstage.”

“You don’t believe that.”

“Course not. But you acting funny makes me nervous.”

“I’m surprised Jasper could influence you.”

“He’s doing no such thing. I have eyes of my own.” Mavis wanted to touch her, awaken what once was so erotic and thrilling that sex sizzled between them. No one ever possessed that kind of spell over her and for so long. “I deserve the truth, after all we’ve been through. Don’t I mean anything to you?”

“You always have,” Bel said and walked on stage.

***

People threw roses and bouquets onto the stage. An assistant handed me my acoustic guitar.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is a night I’ve dreamed of, in so many ways.”

“We love you Bel,” a man yelled from the gallery.

“I love you too,” I said and sat on a barstool. “My grandmother, Naomi Shannon, was a concert pianist and performed here in 1927. Her wish was for me to appear at La Scala. This is for you, Nana.”

I imagined my grandmother in the front row, beaming up at me. She’d be dressed in black slacks, a long string of pearls around a soft blue cardigan, and smoking a thin cigar.

“This song is called, You Can’t Get What You Already Have.” I fingerpicked the strings, singing about how we have it all, of freeing ourselves from worry and guilt, of transcending our fears, and our need to fit in.

The audience, band, back-up singers, assistants, everyone in the house listened as if my words and music were greater than illusions and magic.

When I plucked the last note of the song, from out of sound box flew ten handkerchiefs that fluttered into doves. They circled around the theatre, then came back to land on my shoulders and arms.

The audience rose, applauded, and shouted, “Bel, ti vogliano bene. Bravo!”

***

Claire adjusted my cape. Assistants arranged a circle of fire wicks, pyrotechnics, and a 3D projection set on a gantry. A few of La Scala’s scenery artists and maintenance crews gathered offstage.

I gave the thumbs-up to the stage manager.

The curtain rose to a burst of shrieks, stomping feet, clapping hands. The spotlight blinded me. Alvin thumped a steady beat.

“The magic you’re about to see has never been performed before. The song is called, The Past is Gone.”

The stage lights dimmed. Around me, a ring of flames ignited and blazed. A detonation boomed. Four other Bels joined me, two on either side.

My Bels and I broke into a rollicking song and can-can kick.

The past is gone the future not here.

Why live in the mind? Why live in fear?

Embrace the moment that is the key.

There is no time but now so be free.

We kicked our legs high in the air, to the right—to the left—while repeating the song.

The audience leaped to their feet. They clapped, whistled, and hooted.

We Bels flung off our capes. A circle of fire engulfed the apparitions, spewing faux balls of flames into the rafters and enveloping the stage in a thick vapor.

I hurried down the trap door and pulled the string.

Taking off my mic and ear-piece, I opened the trunk, unstuck the wig, peeled off the tape, and cleaned my face. Heart drumming, I changed my clothes.

Feet scuffled above along with muffled voices. “Encore! Encore!”

The escape hatch opened. “C’mon Bel.” Claire said.

I stuffed everything, including my boots, into the tote bag and locked the trunk. Pulse beating between my ears, I put on my black-framed glasses and cotton jacket, then grabbed the flashlight.

“Bel? You’ve milked it long enough. C’mon,” Claire said.

“You all right?” Soner asked.

“Go down and get her,” Jasper shouted as the crowd chanted, “Encore, encore.”

I pulled the light string and raced through the basement.

“Bel, where are you?” Soner yelled.

The tote bag slapped against my hip as I rushed deep into the darkened basement.

I came to the second door on my left and climbed the stairs. I stuck the flashlight in my pocket and opened the door to the set design area.

***

Several scenic artists in paint splattered smocks worked on a massive canvas spread on the floor. Mozart’s The Magic Flute played softly from a boombox. From out front my band repeated the intro to You Are Never Alone.

Stooped, I carried the tote bag. My shoulder-length white hair was falling around my considerably seasoned face. I walked to a custodial cart with cleaning fluids and brushes on the top shelf. On the bottom rack was a basket of dirty linen and clean rags. I moved the rags aside and hid the tote bag.

“Non dimenticare la biancheria sporca,” an artist said. He pointed his brush at a pile of dirty smocks.

I pushed the cart to the heap of clothes.

Bent over, hair fallen to the sides of my black-framed glasses, I put the smocks into the basket.

The door opened. “Have you seen Bel Shannon?” Soner asked.

“Why would she be here?” the man said in English.

I shoved the wagon forward, away from the set decorators who couldn’t care less about Bel Shannon.

I moved the cart, avoiding the backdrop. Vapor lingered in wisps, floated, then evaporated as it hit the side curtains. The band stopped playing. The house lights came on.

I thrust the cart to the right toward the hallway where a stairwell led down into the audience.

Claire. She carried my cape in her arms—as if it were the remains of someone she loved. I glanced away. If only I could explain to her, tell her.

Perspiration caused the glasses to slide down my nose. I pushed them up. My heart thumped like Alvin’s bass.

From the far right of the stage, I peered at the audience and saw people leaving their seats. Some booed. A woman shouted, “Rip-off.” Fans stood in the orchestra pit, gawking at the stage as if I would reappear. The band and back-up singers wandered around dazed. My assistants, mystified and confused, looked behind curtains and screens.

“She’s not down there. No one’s seen her.” Soner climbed out the trap door. “The guard on the street told me no one came out.”

“She’s inside,” Jasper said. “Keep looking.” Jasper’s voice gave me goose bumps. Seeing him no more than ten feet away, I turned my face and willed myself small and insignificant.

“Hey, you with the cart,” Jasper shouted.

I stopped breathing.

“Have you seen Bel Shannon?”

“No,” I said, shaking my head.

“You dropped something.” Jasper gestured to a rag on the floor.

I picked up the cloth and gulped air as I jostled the cart into the hall.

“Bel. She’s here. I know you are,” Mavis cried. The hurt in her voice made me ache.

I rummaged under the rags, grabbed my tote bag by the straps, and slouched toward the stairs.

La Scala’s security jammed the stairwell. Two of my bodyguards climbed the steps. In character, I visualized myself as tiny and fragile. I said, “Scusa, scusa,” and labored down the steps as I brushed past men I had employed for years.

Seized in the chagrin of the crowd, I became one of them.

I held the tote bag against my thigh and limped to a young woman. In an English accent I said, “Signorina, my legs are weak. Can I take your arm?”

“Of course.” She held out her elbow.

“Grazie.”

I lowered my eyes. My long white mane was falling over rounded shoulders—hope was kept alive as we approached the lobby.

I glimpsed Mavis and Mr. Ponti through the doors that led to the foyer. I hesitated.

“Are you all right?” the young woman asked.

“Just tired.” The two of us entered the packed lobby. La Scala’s security scrutinized the crowd.

Through the windowpanes, I saw reporters poised with microphones. Paparazzi held cameras. Limousines lined up out front. There were blue and white cars with flashing lights. I gazed one last time at La Scala’s high ceilings and chandeliers, the statues and paintings, and the stairs to the balcony—and said a silent good-bye to Nana.

Jasper joined La Scala’s security. I wanted to bolt.

I tucked my arm in the safety of the young woman’s. “Did you enjoy the concert?” I said, hoping to engage the girl, and leaned in as if hard of hearing.

“Yes, until Bel Shannon disappeared.”

Soner rushed to Jasper and whispered something in his ear. Mavis and Mr. Ponti joined them.

I turned away, afraid Jasper might recognize me as the cleaning woman from back stage. I wanted to look at him. The temptation was powerful. But I didn’t dare make eye contact. Absolutely not!

Media hounds waited outside. I lowered my head as I shuffled toward the final exit.

“You’ve been very kind.”

“You remind me of my grandmother.”

A few more steps and I’d be out the door.

***

Once outside, I turned my head away from photographers. I glanced sideways to see if anyone followed, but people jammed the front of La Scala.

“Grazie, signorina. Buonanotte.”

“Ciao,” the girl said.

On the crowded piazza, I continued to hunch over. White strands of hair fluttered across my face. Fog wreathed around lamplights. A throng of people gathered near the Galleria in front of the jumbo-screen.

Ahead was a group of middle-aged women. I joined in, close enough to be one of them.

We walked around the gothic cathedral and crossed the courtyard. The women stopped and watched the JumboTron. It showed chaos inside La Scala. BBC news anchors commented on my mysterious disappearance. The news ticker scrolled, Breaking News! Bel Shannon Missing!

Safe inside the throng of people, I watched along with everyone else as Nana’s steamer trunk was lifted out of the trapdoor. Jasper and Soner looked on. Did they think I was hiding in the trunk? Mavis stood by, crying, as if it were my coffin. Bel Shannon’s final resting place.

Fingers secured around the straps of the tote bag, I ambled away, hearing my name as people passed by.

“What do you think happened to Bel Shannon?”

“She’ll probably show up in Las Vegas, like Elvis.”

They laughed.

So did I.

I walked toward a taxi.

“Bet she’s still in the theatre.”

“A phantom of the opera.”

“Hope she’s okay.”

“Sure she is. It’s all smoke and mirrors.”

It sure was, all smoke and mirrors.

A light rain fell. I raised my naked face to bathe in the cool evening drizzle. With gratitude, I closed my eyes and breathed into my heart.

The curtain on my life opened as I vanished in front of the world.

Table of Contents

DC Diamondopolous is an award-winning short story, and flash fiction writer with hundreds of stories published internationally in print and online magazines, literary journals, and anthologies. DC’s stories have appeared in: Sunlight Press, Progenitor, 34th Parallel, So It Goes: The Literary Journal of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, Lunch Ticket, and others. DC was nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize and twice for Sundress Publications’ Best of the Net. She lives on the California central coast with her wife and animals. dcdiamondopolous.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast