by Norman Simms (December 2017)

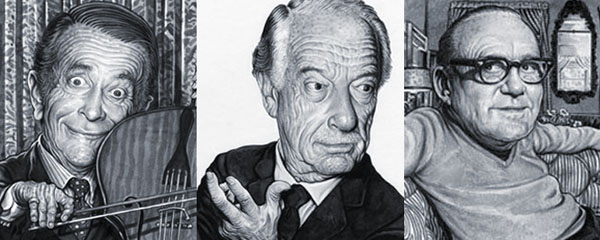

Morey Amsterdam, Victor Borge, and Jack Benny portraits by Drew Friedman

. . . the structure of [Aby Warburg’s] Nachleben is close to that of the Freudian symptom, being not only the afterimage of an old thought that troubles new perceptions, but the phantasmal re-staging of an original traumatic scene . . . the Urszene—that may not have taken place at all (and whose actuality in any case is irrelevant) The Freudian symptomology eschews the distinction between original trauma and later re-elaboration . . . [1]

We can find guides to this multi-layering of intent and methodology in a few examples of Jewish musicians who use jokes to enhance their stage performance and their sense of humour, in all its darker modalities of traditional expression, to deepen the effects of their music. Maybe, also, with a discreet mix of hogwash and ambiguity. For, after all, as Groucho says,

This opus started out as an autobiography, but before I was aware of it, I realized it would be nothing of the kind. It is almost impossible to write a truthful autobiography. Maybe Proust, Gide and a few others did it, but most autobiographies take good care to conceal the author from the public. In nearly all cases, what the public finally buys is a discreet tome with the facts slyly concealed, full of hogwash and ambiguity.[2]

Some of these anecdotes used not so much as proof but as starting points for discussion are gleaned from my own memory as they float by in the breeze of interrupted thoughts; and these Nachleben, or nearly formless revenants of the past, may shape the creative space for the understanding of what may be called Witzenschaft, the wisdom (Wissenschaft) of Jewish humour. While not as cynical perhaps as the cigar-chewed wit of Groucho Marx, my memories are nevertheless not to be trusted as facts, but only as indications of mood, tone and textuality.[3]

As a teenager in New York in the early 1950s, I recall going to a cabaret act, [4] during a bar-mitzvah reception, and someone (at the time, the name meant nothing to me) walked into the spotlight of a darkened room, around which we all sat expectantly, and this person, was holding a cello. He sat down and put his bow in position to play. It turned out to be Morey Amsterdam,[5] and instead of giving us a concert of classical music, as his musical instrument and demeanour suggested, he started cracking jokes. Occasionally, he become silent, took his bow back up as though ready to start some sonata or other piece of serious music, but held it in suspension as he told even more witty anecdotes. Eventually, with perhaps two or three random notes having been heard, we watched him stand up, give the bow a glide in several directions, and then walk off the stage.

[4] during a bar-mitzvah reception, and someone (at the time, the name meant nothing to me) walked into the spotlight of a darkened room, around which we all sat expectantly, and this person, was holding a cello. He sat down and put his bow in position to play. It turned out to be Morey Amsterdam,[5] and instead of giving us a concert of classical music, as his musical instrument and demeanour suggested, he started cracking jokes. Occasionally, he become silent, took his bow back up as though ready to start some sonata or other piece of serious music, but held it in suspension as he told even more witty anecdotes. Eventually, with perhaps two or three random notes having been heard, we watched him stand up, give the bow a glide in several directions, and then walk off the stage.

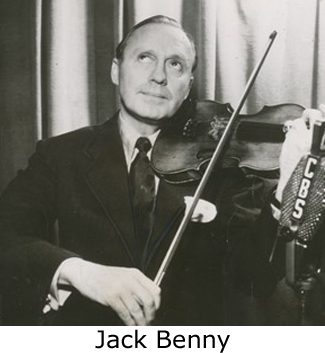

Later I remembered something like this, that I used to hear on the radio. Jack Benny—whom we never saw, of course[6]—would be standing with his man-servant Rochester[7] and always about to begin playing his violin. We knew this because several other characters in the show would say so, directly or indirectly,  and maybe, right near the end, the comedian would actually play a few seconds of melody. What we didn’t know because we thought his music-making was never really very good and his comedy routine a diversion from his parents’[8] ambitions for him to become a famous concert performer, was what Sarah Long and Steve Ember tell us today: “He started as a serious musician before he discovered he could make people laugh.”[9] But what is serious in his case?[10] “While in [high] school,” the two Voice of America announcers say, “Benny got a job as a violin player with the Barrison Theater, the local vaudeville house…sometimes during school hours,” indicating that “serious” about either his music or his other studies he was not; but about being in show business, that he was. During World War One, Jack Benny—he changed his name several times before Ben Kublensky disappeared into history—entertained sailors at the Great Lakes naval Station where he was assigned after his call-up. Audiences loved his jokes, not so much his fiddling, and after the war, when he returned to vaudeville, the violin became merely a prop, and that was how he progressed through his career on stage, screen, radio and television. As Long and Ember further tell us, Benny “was skilled at using his violin to make people laugh.” However, for all his fooling on stage with the instrument, he “could play the violin very well.”

and maybe, right near the end, the comedian would actually play a few seconds of melody. What we didn’t know because we thought his music-making was never really very good and his comedy routine a diversion from his parents’[8] ambitions for him to become a famous concert performer, was what Sarah Long and Steve Ember tell us today: “He started as a serious musician before he discovered he could make people laugh.”[9] But what is serious in his case?[10] “While in [high] school,” the two Voice of America announcers say, “Benny got a job as a violin player with the Barrison Theater, the local vaudeville house…sometimes during school hours,” indicating that “serious” about either his music or his other studies he was not; but about being in show business, that he was. During World War One, Jack Benny—he changed his name several times before Ben Kublensky disappeared into history—entertained sailors at the Great Lakes naval Station where he was assigned after his call-up. Audiences loved his jokes, not so much his fiddling, and after the war, when he returned to vaudeville, the violin became merely a prop, and that was how he progressed through his career on stage, screen, radio and television. As Long and Ember further tell us, Benny “was skilled at using his violin to make people laugh.” However, for all his fooling on stage with the instrument, he “could play the violin very well.”

Like Morey Amsterdam, so with Jack Benny, the modern American Jewish comic shtick had a defining prop, the musical instrument; and somehow, the music that we never really heard but only imagined in anticipation or through a small number of hints, gave a grave and meaningful undertone to the whole performance: for this is what Jews did when they had to leave everything behind in times of crisis and persecution—they brought their love of music, their sensitive souls, and their heritage of intense focus and mental dexterity with them, along with their sense of self-mockery and distrust of authority.

Such a delayed but at the same time evoked memory of a performance also became the explicit and often profound mark of Victor Borge’s career, where a combination of personal nervousness about public performances, cultural traditions of self-deprecatory humour, and specific historical occasions when hiding one’s anxiety and aggression became necessary create a distinctive mode of musical originality. Born in Copenhagen, Victor Borge (1909-2000) grew up in the home of musicians, his father a violinist, his mother a pianist; and they recognized in their three-year old son known as Berge Rosenbaum—what else than a Jewish prodigy! He performed his first concert at the age of eight and then ten years later won a scholarship to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Music.[11]

of personal nervousness about public performances, cultural traditions of self-deprecatory humour, and specific historical occasions when hiding one’s anxiety and aggression became necessary create a distinctive mode of musical originality. Born in Copenhagen, Victor Borge (1909-2000) grew up in the home of musicians, his father a violinist, his mother a pianist; and they recognized in their three-year old son known as Berge Rosenbaum—what else than a Jewish prodigy! He performed his first concert at the age of eight and then ten years later won a scholarship to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Music.[11]

Unlike the American Jewish comedians we have noted already, Victor (who took the stage name only later after leaving Denmark) seemed destined for a life in classical music as a concert pianist. However, three factors weighed against this career: First, the rise of the Nazis, which led him, as a Jew, to abandon Europe, where he was building a reputation as a serious musician for America and where he could see no future for himself or his family, and only later returning to the Old World on tours; this blockage of his career also came at a time when he began to develop his unique combination of joke-telling and playing classical piano. Second, his nervousness in front of audiences who could turn hostile and belligerent because of his Jewish identity combined with his own inner insecurities, led his performances to include anti-Nazi jokes, as well as the signature personal anecdotes that marked his later life this patter giving him confidence as audiences laughed and calmed his moral principles. Thirdly, though Borge never made it part of his routine to identify himself as a Jew or to mystify his mixing of classical seriousness and musical jokes, he never hid his origins or attempted to disparage his musicological knowledge. The outer fears disappeared, of course, when he made his way to the United States, but not his moral concerns for his fellow Jews in Europe, and his life then included both his artistic success as a mix of comedian and pianist and his efforts to rescue and serve the persecuted Jews during and after the Holocaust. While not all his exuberant fans recognized the underlying strands of seriousness in what Victor Borge presented at his concerts—the professional musician who played in tandem with his joke-telling and the comedian whose anecdotal ramblings were based on serious political issues—most critics could feel the tensions and saw in him someone several pegs above Morey Amsterdam and Jack Benny. While Amsterdam and Benny were funny men who grew out of the old American vaudeville circuit, adapting themselves to radio and television, Borge was a serious musician who gave to his performances a comic edge, performances which for the most part reminded audiences of the concert stage rather than the popular music hall.

On the one hand, this kind of wit and playfulness with tonality and allusion can also be seen in many Jewish performers, and may be as much a part of a midrashic personality (the ability to manipulate the constituent elements in one’s life, as though they were texts, in order to make bad things bearable and to ward off melancholia and feelings of guilt arising from within himself) as those neurotic or “eccentric” qualities Stephanie McCallum finds so distressing to a modern bourgeois sensibility.[12]

On the other hand, despite the ease which many west European Jews in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries seemed to make a transition from rabbinical culture to western secular culture, the ease was also an illusion. This was because to become part of the artistic and intellectual elite, they did not only rebel against their parents’s wishes and ambitions and their close community’s bourgeois standards as other French or German young performers did. The Jewish musicians, creative writers and critics has first to break away from Jewish expectations and then enter the dominant society’s matrix of values and tastes—and then break away from that. Yet, all along, what they assumed was acceptance—and somehow believed they looked, sounded, thought, and felt like their fellow young bohemians and rebels—was not. They did not look, sound, think or feel like everyone else, and sometimes only did so on a temporary and superficial level. What the Jewish boys and girls assumed to be a major transition in their personalities and appearances did not fool the goyim, whether they were close associates, appreciative audiences or sympathetic critics, and certainly not jealous rivals, uncomfortable spectators who knew something fishy was going on, and hostile critics who could (because they wanted to) pierce through the disguises and masks.

Thus the musician comedians looked at in this essay played on two old Jewish strategies for survival in an unwelcoming world. Sophisticated patrons of the arts knew that Jewish wit often turned on self-mocking jokes and poses of inferiority, ironic grins and cringing gestures, that sought to disarm hostile attacks both in the pages of the newspaper or in the streets of the city. Such clued-in viewers and listeners also were quite aware that Jews prided themselves on their knowledge, skill and creativity in the arts, a kind of cross-over from the intensities of Talmudic study, just as sharp-dealing in the marketplace had prepared the old ghetto dwellers and travelling peddlers to take advantage of the new open capitalist economy. However, some Jewish entertainers did not feel confident enough to show their pride in full bloom and hence adapted the role of the schlemiel (the person who attracts bad luck to himself and can never shake off the pose of the nervous underling) to that of the concert pianist or classical violinist.

Even the nineteenth-century pianist and composer, Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)[13] claimed that, if it weren’t for some study (“reading” of whatever books, manuscripts or remembered texts of his childhood) he would be either a common vegetable, a cabbage or a mushroom, but especially the latter, “a fungus with a taste for music.” This weird and ridiculous locutin of the musical mushroom or tuneful toadstool resonates in two way in Jewish tradition, the one positive insofar as commentators have understood the mana that fed the Children of Israel in the desert of Exodus as a form of an edible fungus that appeared like dew on the ground, a gift from Heaven, and the other in a negative way as a disease (similar to leprosy) that imparts uncleanness to inanimate as well as living beings:

Mold and fungus must be removed, and, if the buildings cannot be restored to health, they must be demolished.

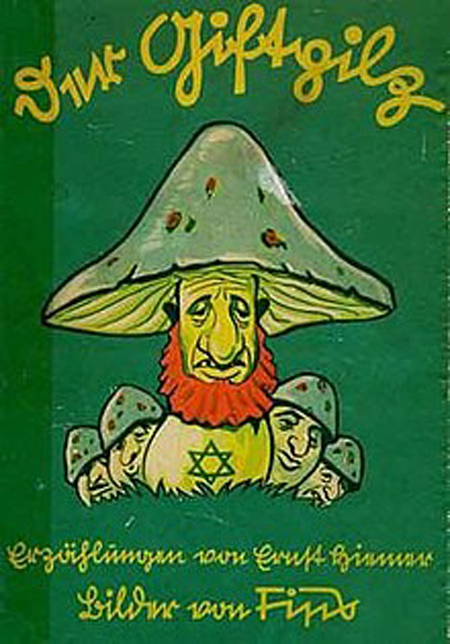

More pernicious, however, is the anti-Semitic notion that the Jew himself is the poisonous mushroom or fungus, as shown in this piece of 1930s Nazi propaganda:

A mother and her young boy are gathering mushrooms in the German forest. The boy finds some poisonous ones. The mother explains that there are good  mushrooms and poisonous ones, and, as they go home, says:

mushrooms and poisonous ones, and, as they go home, says:

“Look, Franz, human beings in this world are like the mushrooms in the forest. There are good mushrooms and there are good people. There are poisonous, bad mushrooms and there are bad people. And we have to be on our guard against bad people just as we have to be on guard against poisonous mushrooms. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, mother,” Franz replies. “I understand that in dealing with bad people trouble may arise, just as when one eats a poisonous mushroom. One may even die!”

“And do you know, too, who these bad men are, these poisonous mushrooms of mankind?” the mother continued.

Franz slaps his chest in pride:

“Of course I know, mother! They are the Jews! Our teacher has often told us about them.”[14]

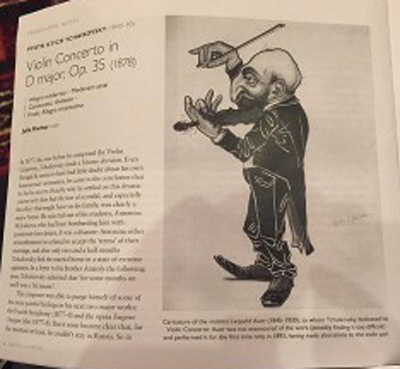

Lest anyone think that such a grotesque image is a thing of the past, here is a “cartoon” version of the famous Jewish violinist Leopold Auer printed in the programme for the BBC’s Proms in 2015. The BBC spokesman tried to pass it off as a joke, of no consequence, and refused to either remove it or apologize, granting only this further insult, “We’re sorry to anyone who was offended by the image choice—this was never our intention.”[15] In other words, most people would not find the caricature (right out of any anti-Semitic rag, such as the Nazi newspaper Der Sturmer) offensive but rather funny and appropriate, and those who don’t, well, that’s just too bad and they’re probably Jews anyway.

“cartoon” version of the famous Jewish violinist Leopold Auer printed in the programme for the BBC’s Proms in 2015. The BBC spokesman tried to pass it off as a joke, of no consequence, and refused to either remove it or apologize, granting only this further insult, “We’re sorry to anyone who was offended by the image choice—this was never our intention.”[15] In other words, most people would not find the caricature (right out of any anti-Semitic rag, such as the Nazi newspaper Der Sturmer) offensive but rather funny and appropriate, and those who don’t, well, that’s just too bad and they’re probably Jews anyway.

Caricatures and cartoons of Jews and other characters during the nineteenth century never reached the depths of depravity the Nazi ideologues created in the early twentieth century, but the animus was building up in France throughout Alkan’s lifetime; and it would climax in the 1890s with the Dreyfus Affair. Innuendo, .jpg) rumour and other insults were sufficient, even among his fellow musicians, critics and audiences to keep him aware that he was never going to be accepted, let alone assimilated into the French cultural elite. Faced with such a situation, and given his traditional background in his father’s household while growing up, Alkan had a number of options when any overt or strongly implied slight was offered. He could play the eccentric fool.[16] However, rather than merely pass off the verbal injury or institutional action, indicating that he was aware but not ready to confront it, he could withdraw, as he sometimes did, for shorter or longer periods, hoping the pain would pass and the specific cause would be forgotten; such withdrawals were never absolute, and Alkan had plenty to do to occupy his time, if not always his social time, by giving lessons privately, composing more and more intricate music, offering his services to the Parisian Consistory for composing, editing and adjudicating its musical life. By his sixth decade, he was resigned to the fact that already his place in the same generation with Liszt and Chopin was fading away and his legacy might not be very strong, he seemed to give more attention than earlier to several Jewish projects related to translations of Scripture and what the Ashkenazi rabbis called “lernin”, study of the homiletic and exegetical writings. For the most part, his musical compositions, both the way they intricate and difficult to perform and the appearance they give on the printed page of dizzying patterns of rising and subsiding waves of notes, suggest an enclosed world of dazzling musical wit, penetrating logical structures and a crazy, wild assertion of independence from the staid formal norms of academic composition.

rumour and other insults were sufficient, even among his fellow musicians, critics and audiences to keep him aware that he was never going to be accepted, let alone assimilated into the French cultural elite. Faced with such a situation, and given his traditional background in his father’s household while growing up, Alkan had a number of options when any overt or strongly implied slight was offered. He could play the eccentric fool.[16] However, rather than merely pass off the verbal injury or institutional action, indicating that he was aware but not ready to confront it, he could withdraw, as he sometimes did, for shorter or longer periods, hoping the pain would pass and the specific cause would be forgotten; such withdrawals were never absolute, and Alkan had plenty to do to occupy his time, if not always his social time, by giving lessons privately, composing more and more intricate music, offering his services to the Parisian Consistory for composing, editing and adjudicating its musical life. By his sixth decade, he was resigned to the fact that already his place in the same generation with Liszt and Chopin was fading away and his legacy might not be very strong, he seemed to give more attention than earlier to several Jewish projects related to translations of Scripture and what the Ashkenazi rabbis called “lernin”, study of the homiletic and exegetical writings. For the most part, his musical compositions, both the way they intricate and difficult to perform and the appearance they give on the printed page of dizzying patterns of rising and subsiding waves of notes, suggest an enclosed world of dazzling musical wit, penetrating logical structures and a crazy, wild assertion of independence from the staid formal norms of academic composition.

While he seems to compose within the acceptable norms of his own time and place in Western Europe during the mid-nineteenth century, Alkan nevertheless makes a peculiar and specific use of those commonplaces, approaching in this way what would later be termed, in racialist, derogatory terms, “decadent” or “degenerate”. It seemed to some of his harshest criticvs that this Jew had no soul, only an extravagantly logic-chopping mind, that is, that he practiced pipul (rabbinical casuistry and spiritless variations on basic themes). Anti-Semites like Wagner did not believe the Hebrew soul could be truly passionate creative. Put more politely by Peter McCallum, Alkan’s “musical ideas…were often pursued with experimental, sometimes obsessive rigour” and reached a “persistent obtrusive dissonance”[17] that became later the marks of radical musicological sounds in the ten-tone row and other post-modernist forms. But that is not all. “With wry humour, Alkan inserts dog barks in the central section” of one of Chants, “a joke he seemed to like, for he also used it in Le Festin d’Ésope, the bizarre set of variations that concluded the Études, Op. 39”.[18] If these stylistic quirks and jokes seem, on the one hand, to stigmatize the composer’s character as qualities of mental illness, at the same time, at the very least, they show him to be aware of his own status as the outsider and willing, as a Marrano-like Jew[19] to make fun of himself as well as of the society that barely tolerates him.

Alkan might have felt uncomfortable at many times and in many ways because of these neurotic symptoms, but not enough to be debilitated by them or even to wish to be rid of them since they were spurs to his creativity. In respect of an Allegretto in this collection of songs that Peter McCallum is commenting on, the musicologist suggests a reading that could just as well be generalized to the whole of Alkan’s mental condition and his career, “the work begins and ends in with an unresolved dissonance, which is relieved only during the central section, like a sharp emotional pain that one manages to forget for a moment.”[20] For both the technical analysis of the Jewish musician’s compositions and the more psychohistorical evaluation of his mentality reveals that he alternated—not always evenly, not always in a sustained way—periods marked by “manic and grotesque moods”[21] and intense serious concentration on the historical and intellectual roots of the rabbinical personality in Scripture, Talmud and speculative philosophy. Only rarely do the critics or interpreters catch his jokes, let alone his witty allusions to rabbinic texts and ideas. Or, to put it another way, in an episode when Jack Benny having been held up by a robber on the street and told “Your money or your life,” waited several agonizing silent minutes, his arms folded, until at last he said to Rochester’s prodding: “I’m thinking. I’m thinking.”

[1] Camilletti, Leopardi’s Nymphs, pp. 30-31.

[2] Groucho Marx, Groucho and Me: The Autobiography of Groucho Marx (New York: Manor Books, 1959) p. 11.

[3] I put aside altogether my experiences a teen-age musician in New York and the jokes I played during performance at bar mitzvas, sweet-sixteens and wedding receptions, or more pertinent the tricks audiences tried to play on me at one gig or another.

[4] This memory has not been interfered with by time and its layers of subsequent experiences since, in all truth, that was the one and only time I ever went to a nightclub.

[5] Aharon, “Morey Amsterdam” Jewish Biography (9 December 2009) online at http://jewishbiography. blogspot.co.nz/ 2009/12/morey-amsterdam. This is one of the few sources that includes the cello: “Morey Amsterdam [1908-1996] was born in Chicago, Illinois, the son of Austrian immigrants Max and Jennie (Finder) Amsterdam. He began working in vaudeville in 1922 as the straight man for his brother’s jokes. He was also a cellist, a skill which he used throughout his career.” See also Tom Vallance, “Obituary: Morey Amsterdam” The Independent (4 November 1996) online at http://www.independent.co.uk/ news/people/obituary-morey-amsterdam-1350735. “…though Morey studied both the cello and saxophone, he preferred comedy, and as a teenager entered vaudeville, using the cello as a prop while telling jokes.”

[6] A quip that could work then but not these days was that a radio was a television with a no inch screen.

[7] Edmund Lincoln Anderson (1905 –1977) played the part of Benny’s valet, the gravel-voiced Rochester van Jones.

[8] Meyer and Emma Kubleksy of Waukeegan, Illinois, near Chicago, emigrants from Eastern Europe in the 1880s.

[9] Sarah Long and Steve Ember, “Jack Benny, 1894-1974: He Won Hearts Mostly by Making Fun of Himself”, People in America series, Voice of America (10 October 2009) online at http://manythings.org/learningenglish. voanews.com/ a/a-23-2009-10-10-voa1…/129949.

[10] Another commentator, Hunter Hawk claims, “Jack Benny was a decent violin player but not what anyone would call accomplished. Even his own daughter admits this in a bio she wrote (using the notes from his autobiography that was never published). She said he could hold his own on a violin.” See his blog The Straight Dope (1 January 2009) online athttp://boards.straightdope.com/sdmb/showthread.php?t=499937.

[11] “Victor Borge (1909-2300) Jewish Virtual Library online at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrarty.org/source/ biography/Victor_Borge.

[12] I have addressed this question before in terms of a suggestion that all artists and other geniuses by their very nature must be dysfunctional anti-social: Norman Simms, “The Artist and the Soul of Genius: A Sidelong Glance” Clio’s Psyche 18:4 (2012) 442-445.

[13] He was born Morhange but changed the family name later to his father’s first name.

[14] Randall Bytwerk, the online editor of this text explains that “This story comes from Der Giftpilz, an anti-Semitic children’s book published by Julius Streicher, the publisher of Der Stürmer. He was executed as a war criminal in 1946. This summary and partial translation is taken from a 1938 publication issued by the ‘Friends of Europe’ in London, an organization to which I have not been able to find a successor to request permission to reprint.” Taken from Bytwerk, Bending Spines: The Propagandas of Nazi Germany and the German Democratic Republic (Michigan State University Press, 2004) and available online at German Propaganda Archive (Calvin College) http://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/story2.

[15] Shiryn Ghermezian, “BBC Apologized for Antisemitic Caricature of Famous Jewish Violinist in Concert Program” The Algemeiner (18 September 2015)

[16] Never, of course, as Ed Wynn did in his famous defining role as “The Perfect Fool.” Wynn could never get over his aversion to performing on radio, unless he came on stage in full costume with props and played before a live audience. Perhaps his most important role was that of Mr Dussel in the film version of “The Diary of Anne Frank,” for which he won an Oscar in 1959.

[17] Peter McCallum, “Charles-Valentin Alkan and his Recueils de Chants,” Charles-Valentin Alkan: Complet Recueils De Chants, Vol. 1 (2/26/2013) Toccata Classics Catalog #: 157 Spars Code: DDD p. 3. See online at http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=859462

[18] McCallum, “Charles-Valentin Alkan and his Recueils de Chants,” p. 6.

[19] The assimilated or converted Jew tries to separate him or herself from the rabbinical community, its practices, and beliefs, while the Crypto-Jews attempts to mask the inner core of Judaic character and personality under the pretense of the host society’s Christian versión of secularism. The Marrano (derogatory term that it derives from: pig, whore, heretic) remains unsure of himself, confused by the options available to her and unwilling to make any choice at all.

[20] McCallum, “Charles-Valentin Alkan and his Recueils de Chants,” p. 8.

[21] McCallum, “Charles-Valentin Alkan and his Recueils de Chants,” p. 9.

____________________

Norman Simms taught in New Zealand for more than forty years at the University of Waikato, with stints at the Nouvelle Sorbonne in Paris and Ben-Gurion University in Israel. He founded the interdisciplinary journal Mentalities/Mentalités in the early 1970s and saw it through nearly thirty years. Since retirement, he has published three books on Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus and a two-volume study of Jewish intellectuals and artists in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Western Europe, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise; Dust and Ashes, Comedians and Catastrophes, Volume I, and his newest book, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise: Dust and Ashes, Falling Out of Place and Into History, Volume II. Several further manuscripts in the same vein are currently being completed. Along with Nancy Hartvelt Kobrin, he is preparing a psychohistorical examination of why children terrorists kill children.

More by Norman Simms here.

Please help support New English Review.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link