by Jillian Becker (December 2020)

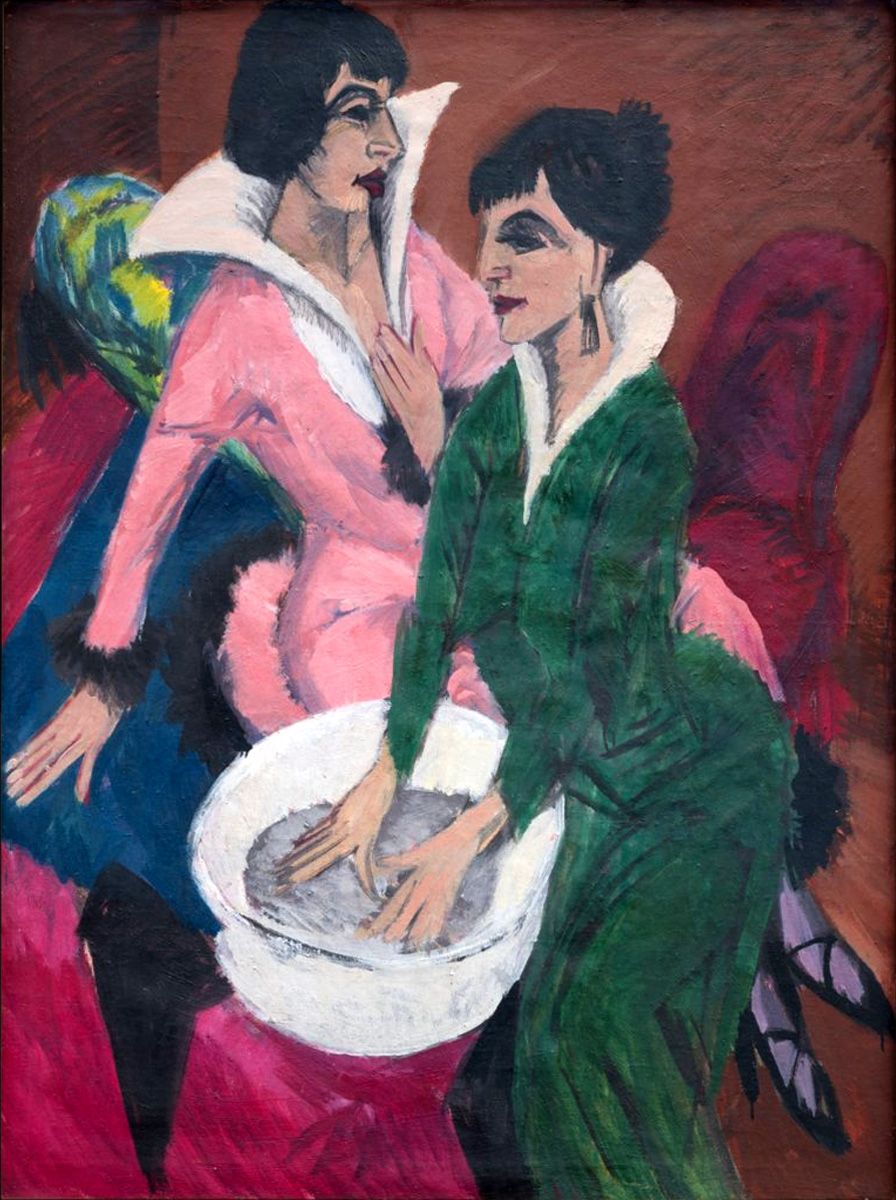

Two Women by a Sink, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1913

In her early adult life, Doris Lessing was a Communist. So, when, very early one morning in 1967, I shared a taxi home with her from a party (we each had a house in north London), I did not expect to enjoy harmony of opinion with her; but I tried to light a spark of conversation. I forget what we said, only that my opening remark was meant to be congenial, and that her dull response extinguished the spark. For the rest of our ride in the small hour we made small talk. And though we sat side by side in the back seat of the cab, to my mind we were far apart, the Iron Curtain hanging between us.

Later I learned that she had turned against Russian Communism years before we rode together. She had been a member of the Communist Party and an admirer of Stalin, but had abandoned the faith soon after the tyrant’s death. She had not choked on the forced famine in the Ukraine when at least four million and possibly as many as ten million starved to death, nor on the gulag system and brutal exploitation of prisoners as slave labor. But the cause lost her when Soviet Russia invaded Hungary in 1956 to put an end to that country’s struggle for liberty.

By the time I met her, her reputation as a writer was well established. Her first novel, The Grass Is Singing, was published in 1950. It is a tale of poor white farmers in what used to be called Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where Lessing (born in Iran in 1919) grew up. It is harrowing, dramatic, believable. After that, she wrote a lot of autobiography—some volumes as fiction, some as fact—and quite a lot of science fiction.

Another of her realistic novels, The Good Terrorist, was published in 1985, about 16 years after the first eruption of middle-class terrorist groups in Europe that crippled and killed fellow citizens with bombs and guns in the cause of New Left ideology.[1] It is about a group of young, vaguely Marxist revolutionaries living in a “squat” in London. The story is an extended joke, plotted—consciously or not—along the lines of Jane Austen’s Emma, in which the protagonist means to be wonderfully helpful to her friends but only succeeds in doing them harm. The benign intentions of Alice, the “good terrorist,” also drive her to struggle with bureaucracy in order to have the group’s communal occupation of a condemned house temporarily legalized. She paints the rooms and gets repairs done. She buys healthy food and cooks it for everyone and anyone who turns up to consume it. She gets the money they need—by stealing it. One after another, comrades fall victim to her kindness. Eventually the group, as a group, decides to commit mass murder for the benefit of humankind. Alice helps them purloin a car to hold their home-made bomb. They park it next to a department store in Knightsbridge. The explosion kills and injures an unspecified number of people. We are told nothing more about the massacre. It cannot be examined because agony and death do not fit with the mood of a literary joke.

As a work of fiction, The Good Terrorist is well made and entertaining. But the choice of terrorism as a theme – which made it a document of its time – renders it morally myopic, casually cruel. If the author had given more thought to the atrocity itself, she might have seen that such a culmination to the narrative discredits its light-heartedness. She might have felt that terrorism is not a fit subject for joking. Certainly, she had come a long way from her own Communist faith to be able to regard the fanaticism of young Marxist idealists with irony—but only with irony, not with disgust and unqualified condemnation. The insouciance of the novel implies what the older New Leftists said all too indulgently of the young terrorists in Germany: “Their hearts are in the right place, but their methods are not acceptable.”

The Good Terrorist is, however, an anomaly among Lessing’s works. Irony, light-heartedness, joking is not characteristic of her writing or her temperament. It seems that only a looking back at her Communist youth could elicit it, the result of a conflict between a need to excuse an outgrown passion and a mature rejection of it. Disapproval brushed with forgiveness.

Twenty-three years earlier she had dealt seriously, at great length, with the theme of Communist commitment and the outgrowing of it in The Golden Notebook, her most famous novel, published in 1962. In more than 600 pages, the book discloses the author’s opinions and way of life, chiefly through a dialogue between two “free women.” Anna and Molly descant and yet again descant upon love affairs with men and mental engagements with Communism—or vice versa. They are disenchanted with both, though they still consider Stalin to be “a great man.”

One of them keeps notebooks whose contents are supplied to the reader for no discernible reason. Description in the narrative is banal and purposeless. (“Molly stood slowly wiping glasses on a pink and mauve striped cloth . . .” What difference would it make to the scene or to the subjects of the women’s conversation, or how would it rouse any required thought or feeling in a reader, if the cloth had instead been dotted blue and yellow, or had no colors on it at all?) A lack of point in the choice of detail typifies the novel. There is no story, no characterization, no mystery, no tension, no excitement, no drama, no wit, no humor, no depth, no style, no illumination. But though I found it a bore, it was a top favorite of feminists; a veritable “bible” of the women’s “liberation movement.”

Lessing’s apostasy from Communism was effected with difficulty. Once it was accomplished, she needed a new faith, and found it in a book titled The Sufis, by a proselytizer named Idries Shah. She wrote that it “changed” her. Of all the books she had ever read, she declared, it was the one that affected her most strongly. She recommends it thus (in her typically clanking prose):

“The Sufis is quoted now as source material in a dozen different disciplines and in countries East and West. But this is not my personal concern. I continue to find the book full of information, revelation, a mine of thoughts and ideas. I reread it from time to time and always find something new, which can only be said about ‘real’ books.”[2]

A number of women I knew were similarly entranced with the message that Idries Shah brought them. They embraced the Sufi faith, and kept it even when their guru, with his brother Omar Al-Shah, caused a scandal in the world of literature.

It began when Omar Al-Shah persuaded Robert Graves that Edward Fitzgerald’s English version of Omar Kayyam’s Rubaiyat was all wrong; that Omar Kayyam was not the atheist he was generally believed to be. A relation of the Shah brothers living in the far east, they claimed, possessed the original script, and the verses were clearly the work of a Sufi.

The Shahs made a series of excuses for not producing the original script. But they brought an English translation to Robert Graves. From these verses, Graves made his own version of the Rubaiyat of Omar Kayyam and published it. Scholars asked to see the translation he had worked from. They found that they were in fact a selection of drafts made and discarded by none other than Fitzgerald himself. But even when it was established that no such document as the Shah brothers boasted of existed, or had ever existed, and the claim was a hoax, Graves would not accept that he had been deceived. He rejected the finding indignantly, insisting that he had not been taken for a ride by “a gang of Oriental crooks.”

And despite the proof of Idries Shah’s untrustworthiness, Doris Lessing kept the faith.

How will Doris Lessing be remembered? Perhaps not at all, now that fashionable intellectual opinion on the Left has diluted feminism in the mix of creeds called “intersectionality” and replaced oriental cults with a variety of Marxist retreads in a late revival of Communism. What will remain to commend her? She had a small talent for writing, a huge capacity for exertion. I doubt that a search of her substantial oeuvre would yield one pithy aphorism, one original insight, one memorable phrase or sentence.

Yet she may have been securely memorialized when the inscrutable Nobel committee awarded her its prize for literature in 2007. I think it was a lapse of judgment. (There seems to be general agreement that misjudgment is a failing to which Nobel literary judges are highly susceptible.) Among the 603 recipients of the prize between 1901 and 2020, there are some who surely deserved it, among them —especially—Kipling, Yeats, Thomas Mann, Patrick White, Saul Bellow, Samuel Beckett. But Doris Lessing and not Tolstoy, Chekhov, Ibsen, Stefan Zweig, Arthur Schnitzler, Anna Akhmatova, Mark Twain, Robert Frost . . . ?

[1] I wrote a book about the young German terrorists. Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang was first published by J. B. Lippincott, New York, in 1977, and subsequently in many editions, countries, and languages.

[2] From a book that changed me, Time Bites, by Doris Lessing, Harper Collins, New York, 2004.

__________________________________

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal (Europe), Encounter, The Times (UK), The Telegraph Magazine, and Standpoint. She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast