Tales of Rulx: Enter Reynard

by James Como (December 2017)

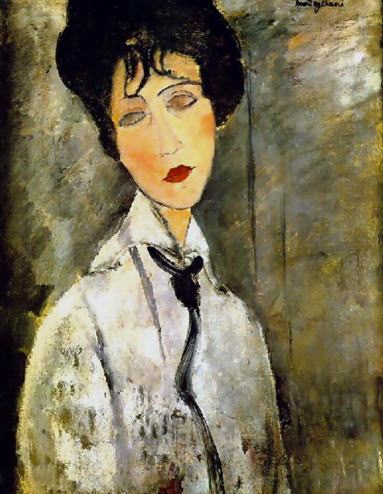

Woman with Black Cravat, Amedeo Modigliani, 1917

1.

This, from his two-man table on the sidewalk in front of the Cafe Haiti in the middle-class Miraflores district of Lima, Peru: Giovanni Carfagna in 1968. One moment he is gazing across the la Diagonal into the middle distance of the Parque Kennedy. During a bright and breezy weekday lunch hour—rare for a July winter—Peruvians come and go, pause and chat. Carfagna sips his espresso (the bean from the jungle surrounding Tingo Maria is his favorite) and ponders Plato’s theory of archetypes. Objects we regard as real, wrote the Greek, are mere shadowy projections of the highest reality, which are the ideas of those objects in God’s own mind—more or less.

Then, in the next moment, he beholds an archetype itself: the very Idea of a Woman’s Perfect Bottom, only not in God’s mind but here come to earth. Not twenty-five meters away, sheathed, caressed—a perfection concealed and revealed, the very firmness and bounce of the beckoning ideal.

Sure he had been thinking, but now he knew that several seconds ago his gaze had become a stare. And so he realized that he had been enjoying several different perspectives and had come to witness an absolute singularity: this archetype held up from all angles, as any archetype must, of course. In stillness and in motion, when she of the ideal bent—bent at the waist—to kiss (a child. her child?) in its stroller, then when she arched her back, feet wide apart, knees locked, and arms akimbo in a long, languorous stretch: from these views and in these many movements the perfection sustained itself, shimmeringly, oh-so-easily, and achingly unrelenting.

“So Carfang,” continued Rulx, Carfagna’s friend and colleague and the other man at the table. “Do you see that the story of the world is at its heart religious?”

Rulx, though the younger man, was Carfagna’s senior at the Institute, a Professor (and a Full Professor at that, by far the youngest in its history, but not yet a Senior Fellow). But no matter; Rulx would tweak the Italian by tweaking his name.

“Roscoe. Roscoe. Roscoe.” Carfagna gave as good as he got. Rulx’s given name was Reynard, “roscoe” being the subordinate’s own tease, knowing, as he did (both being historical linguists, or philologists), that Rulx knew that Carfagna knew that roscoe was old gangland argot for gun.

And that Rulx hated guns.

“. . . and so any effort”—Rulx would not be denied—“to reject either the reality of God or his ubiquity is rather like Hamlet trying to deny Shakespeare.”

“Rulx! Silencio Rulx! For once, no talking, just looking.”

Following the direction of his friend’s stare Rulx did look. And as he did so, this woman turned and looked directly into Rulx’s eyes, her face ablaze with a smile, so that Rulx saw her full beauty—Peruvian beauty, than which, Rulx knew, there is no greater beauty, unless it is Russian beauty.

Carfagna did not notice the woman’s face.

“Oh, Reynard, we behold the greatest narrative ever told!” Carfagna was beside himself with that rarest of states: genuine awe.

“The nape of her neck, and then the widening of her back, at once delicate and commanding, together foreshadowing the unfolding of the plot below. Do you see it, Reynard? Do you see it? The small of her back also pulls the eye, teasingly, until the imperial denouement, and the damage has been done. Our appreciation has become longing, Reynard. Longing. Might we touch that beauty? No matter: we are vanquished.”

Rulx had already risen, slowly and with consummate grace—Rulx never moved ungracefully, gracefulness being one of those traits, like his manner of dress, that made him seem a very handsome man, though he was not handsome at all. He had recognized the woman.

The great beauty was unchanged. No man—not the most ephemeral passerby who merely glimpsed it—would ever forget that dazzle; but any man who dwelt upon it, any man with even half a soul who came to know it well, would be saddened forever by its aloofness. It made a man brittle.

2.

Here is Reynard Rulx, eighteen years old, sitting on a stone bench in the plaza de armas of Moquegua, southern Peru, in 1962. The order of the day for Moqueguans, as of every single day, is boredom, for here nothing changes. Then, just when the few dogs and fewer people are bound for their siestas in whatever shade they might find, Rulx notices the appearance, some forty meters distant, of a young woman. Dressed in a purple habit and, he sees, discalced, she strolls, with a great swaying insouciance. Will she pass him by? Rulx won’t take that chance.

“Buenas tardes, senorita.”

“Good afternoon to you, senor,” grammatically formal.

“That garment is very lovely on you, senorita, if you will permit me to say so. Would you care to join me here in my small kingdom?”

“You may, and I thank you, sir. And I very well might,” she responds, peering down at Rulx, emerald green eyes aglow and one eyebrow raised preternaturally, “if I knew your name.”

He nods. “My apologies, senorita. I’m quite taken out of myself. I am Reynard Rulx, and I am visiting from my home in Bruges, Belgium. May I ask the lady’s?”

“De todas maneras.” Both seem to enjoy a style of exchange that has been out of fashion for four centuries. “I am Lola Monteiro, of Lima, and I am visiting my stepfather’s farm, which has no electricity or running water. It is neither exciting nor amusing. But I do have one friend here. You see him there where I entered the plaza. He should not be here at all, of course, as he is a horse. I am just back from the river, where I baptized him. Now he is El Negro, because he is so white. I wanted him to see our church.”

Rulx laughed loudly, which was rare for him. “Well, if you were to honor me by sitting a while, Senorita Monteiro, you might have a second friend, and I my first.” So she sits, and, at once and inexplicably relaxed, they speak casually and as old friends. Reynard learns that Lola was nearly nineteen and has sworn to wear their purple habit during daylight hours (this as a promise to El Senor de los Milagros), and that she often dates older men but was not now dating anyone.

“You know,” he said, “Leslie Caron looks just like you, only not quite as . . . as . . .”

“I know,” she interrupts after a short wait, “I hear the Caron comparison very much. I must say I like it, I like her a good deal. Do you know who reminds me of you?”

“The young Jean Gabin?” asked Rulx.

“So you know him? No. No one looks like that guy, young or not. No. The other Jean. Jean Paul Belmondo.”

“Belmondo!” exclaims Rulx. “But he has a bulbous nose and blubbery lips and—”

“Ah. But I did not say you look like him, only that he reminds me of you. Anyway, you left out his eyes and jaw and chin. Very handsome. But also smart and funny. And athletic. I bet you are athletic, Reynard.”

Lola learned that he was, as gymnast, boxer and fencer; that he was Flemish; that he had three older brothers; that his parents were teachers who had fought in the Resistance during the Nazi occupation (“in spite of their detestation of the French,” added Rulx); that he was in Peru to study culture and communication; that he was doing so to complete his doctoral dissertation; and that he was nineteen years old.

“Your doctorado? Really? At nineteen? Are you some sort of genius?” Her smile revealed her disbelief as well as mild mockery.

“As it happens, yes. I expect to be Dr. Rulx before the year is out. It will drive my brothers crazy but make my parents very proud.”

They were both silent for a moment. Then he asked, “do I still remind you of Belmondo?”

“Yes. Oh yes. Even more so now.”

After nearly an hour of such talk two facts would have been evident to any onlooker, if there had been one. First, Rulx already may have been in love. Second, of the two only Lola knew it. The sun was scorching, with not even a whisper of a breeze.

“Reynard, would you like to do something very interesting? It might even help with your research.”

“You mean something more interesting than sitting here with you?”

“No. Not that interesting, but different. My stepfather is Ciro Lombardia and he heads the local Accion Popular. I myself am of that party. We expect our candidate to win the presidency this year. His name is Fernando Belaunde Terry, and he has potential for greatness. Tomorrow my stepfather is hosting a dinner for him. Most people of standing and wealth of our small departamento will be at our home. I hereby invite you as my personal guest.”

Rulx was silent, his smile fading. “I don’t like politics.”

“Neither do I,” answered Lola, “but I like this man, and I love my country, and I would like to know what you think of him. Besides, there is a sideshow.”

Rulx’s smile returned, but he said nothing.

“Yes. A sideshow—and it could become a spectacle unto itself.”

“Fine then. What is the sideshow.”

“It’s a she. Beatrix Vivar. She is reputed to be the biggest”—Lola paused and looked about ostentatiously—“puta in all Peru. But that may be owing to her great beauty and manner of dress.”

“Will you be barefoot?”

Lola grinned broadly. “Not at first. I cannot. But if you pay as much attention at the dinner as you have this past hour I promise you will not be disappointed. The farm is La Merced, dinner is at eight. Do not arrive before nine unless you want my mother to think you rude. Now I must see to El Negro, who has grown impatient.”

Reynard, gently snatching up Lola’s hand, kissed it and, without looking up, said “thank you.”

Rulx did arrive at 9 p.m., and still he arrived first. A grim servant provided a shotglass of straight algarovina (thus showing her disapproval) and invited him to stroll about the patio, as he pleased. Instead he settled into a chair with a collection of Ricardo Palma’s Tradiciones, the only book in plain view. Thoroughly absorbed, he jumped to his feet when, as it happened, the mayor of Moquegua and his wife arrived at 10 p.m. in the company of Mr. Lombardia who, intuiting the identity of his first guest, made the introductions. For the next half hour ever briefer chats were interrupted by more arrivals.

In all, fifteen people were present when Mrs. Lombardia and Lola emerged from a dark hallway into the sala. The older woman bore her dignity easily and without affectation; that is, even with mantilla and fan the lady somehow seemed quite down-to-earth. Lola, on the other hand, was breathtaking and knew it. Nodding to people on her left and right she walked directly to the smitten Reynard, kissed him on both cheeks, took his hand, and turned to walk with him back to her mother.

Then Beatrix Vivar made her entrance. Tall, elegant, tightly clad, though at second glance less immodestly than one would have thought, she was also softer of feature than Rulx had expected. Her face beamed warmth, a perfectly proportioned softness and purity of line: nuance without angularity. A face that inspired men to ever greater manliness but not concupiscence. Remarkably, noted Rulx, she wore no makeup whatever, a stark contrast to every other Peruvian woman he had ever seen. The room actually fell silent.

Five minutes later, at nearly 11pm, Mr. and Mrs. Belaunde arrived. The applause was spontaneous, sincere, loud, and prolonged. It accompanied a collective migration from the sala into the comedor, where each of the twenty diners found a place card. Reynard was vastly disappointed to see that Lola was seated next to the candidate, who, at the head of the table, was at some distance. But dismay soon dissolved into astonishment. As he turned to his left, prepared to assist the woman there, he saw Beatrix Vivar, standing erect and quite still, looking directly into his eyes, her smiling face ablaze with transcendent grace.

She waited futilely then pulled out her own chair, never taking her eyes off Reynard. As she sat she invited him to do so, and when they were settled she abruptly turned away to speak to the person on her own left. When Reynard came to his senses he saw Lola, eyebrow raised and emerald eyes aglow, tapping her chin with a single finger.

Rulx did not know what was expected of him and was unsettled by the sense that something certainly was.

At that realization his spirits actually rose. He had been a Visiting Scholar at the University of San Marcos for six months, had traveled the country widely and possessed a broad second-hand familiarity with Peru, an object of long-standing interest that he attributed to its archaic past and romantic geography. He found in this country a new order of strangeness, a meta-strangeness. Everything about Peru, from its fruit, to its mores, to its entropy and, apparently, even unto its female beauty, was above and beyond all conventions of any of the several cultures he knew, and often of physical sensation as well. So here he was in a sort of laboratory.

Then he heard a young woman.

“But she is nothing but a chola! Of what use can she be?” her tone dribbling contempt.

Rulx responded reflexively. “Excuse me, senorita, but is that not an excessively derogatory term, demeaning beyond . . . beyond the necessary?”

“Excuse me, Reynard,” Lola interjected.

“I mean chola. Surely it might innocently describe a particular ethnic group in this extraordinary country, but as commonly used it just as surely is intended to demean that group, to imply servility, social unworthiness, even sub-humanity.”

The room was silent, all eyes on Rulx.

“But, Reynard, just as surely you over-interpret a . . . how to say it? . . . in English, a figure of speech.”

“Perhaps. Many such figures are ugly.”

The girl herself remained silent, but, to the surprise of no one, the mayor’s wife intruded. “Mr. Rulx, why make a dispute out of a mere word? Does that not assure that conversacion will become discusion?”

Rulx knew the meaning of discusion in Peru: “heated dispute, always unwelcome.” There was no distinction between nasty quarreling and healthy argument, the absence of which in this culture—at least socially—maddened him.

“Pues, senora, I do not believe any word—not even “the” or “an” —are ‘mere’. And in this particular instance, my authority is the great Peruvian lexicographer Juan de Arona. In his Diccionario de Peruanismos he defines cholo. I’m able to quote him. ‘One of the many castes that infest Peru.’ He then describes their descent to the coast and ambition to rise socially as an excess of democracy. Clearly—”

In that instant three things happened almost at once.

He heard Mrs. Lombardia. “Joven! Por favor.” Her tone could not have been more condescending, nor her face any redder. “You presume to be at a seminar. Yet this is a dinner party!”

His eyes darted, by no will of his own, to Lola, who was glowering.

“Marita”—Belaunde himself now, using his hostess’s pet name—“now Marita. Mr. Rulx has made a useful point. One of which we must be continually reminded. Is it not the great Dr. Samuel Johnson, Mr. Rulx, who tells us that people need to be reminded more often than instructed? Moreover, Marita, he has argued from no less an authority than our own unparalleled expert! Well done, Mr. Rulx! I do hope we might speak further.”

Reynard barely heard Belaunde, because he heard Beatrix whisper, “let us chat briefly when we can, Reynard, before we part this evening.” Thereafter, the company and its conversation settled as though nothing had happened.

After dinner, back in the sala, Lola approached Rulx, who was more solitary than a leper. “Reynard. Do not ever embarrass me or mine like that again—assuming another opportunity to do so, which is unlikely. On the other hand, you seem to have impressed the next president of the republic. Come with me.”

As they approached Belaunde those speaking to him withdrew, as though they understood his wish to speak to the young man.

“Senor arquitecto”—as it happened, the man was not an outstanding arquitect but was a commanding teacher of architecture—“ this is my . . . friend . . . the presumably brilliant Belgian Reynard Rulx, from Bruges, who is visiting towards the completion of his doctorado. Which, as we now know, has to do with language.” Both men watched her as she swayed back to the group. When Reynard turned, he found Belaunde already looking at him.

The older man took Reynard’s extended hand in both of his own and, smiling warmly, spoke in English.

“You are learning about our culture, Mr. Rulx, and tonight provided a valuable lesson.”

“Yes sir. I have much to learn. By the way, I prefer Flemish to Belgian.”

“I see. I will remember that. So, you provided us with a valuable lesson. I assume you know Dr. Johnson.”

“Oh yes. Yes indeed.” And then Reynard fell silent.

“Is there something on your mind, Mr. Rulx? Please . . . ”

“Have you spent much time in Texas, Mr. Pres—Mr. Belaunde?”

Belaunde laughed so loudly the company turned to look at him.

“Let us not . . . jinx? Is that the word? . . . Let us not jinx my opportunity, Mr. Rulx. Yes. I was a student at the University of Texas in the thirties. It is in America that I came to admire Mr. Roosevelt. How could you know?”

“The vowels, sir. They are most distinctive. And, yes, ‘jinx’ is the right word.”

“Remarkable, really, especially for such a young man. Believe me, I am not condescending. Mr. Rulx, please make a point of visiting me sometime down the road. Hopefully by then you will know my address!”

Then there occurred a remarkable thing: the company broke into applause. Reynard blushed and Belaunde, smiling broadly, turned to rejoin his friends. Rulx had never before come to like anyone so much in so short a time, nor would he in the future.

As soon as the applause died down and the company returned to its tertulia, Beatrix, already near the door, caught Rulx’s eye and beckoned him with a tilt of her head. He did not move directly; in fact, the gesture nearly paralyzed him. But her smile unfroze his limbs and he ambled over, self-conscious in what he took to be his utter conspicuousness.

When he was close enough, Beatrix tilted her head forward with her left cheek turned for a social kiss. Reynard obliged. She quickly presented her other cheek and as she did so lightly touched Reynard’s right hand with her left. As he repeated his part of the ritual she turned and left, a servant already waiting at the opened the door. Of course Reynard stared, but then he started at the realization that she had left a piece of paper in his hand.

After a few seconds, as he wandered out the door, he thought of velocity: it occurred to him that for all its incipient entropy Peruvian culture certainly did not inhibit the currents of Peruvian High Society. He read as he walked; the note was an invitation.

Rulx’s life—his plans, goals, higher aspirations, even his view of himself—would change utterly. After this evening, five years would pass before he would again lay eyes on Beatrix, there, in the Parque Kennedy, across the Avenida Diagonal.

3.

Rulx moved with astonishing speed. Carfagna (who had never met Beatrice but had heard of her as one hears of a legendary figure)—Carfagna also was on the move. What they saw was a strange tableaux. Standing to the woman’s left, farther from the two friends, was a huge man whose right arm was around the woman’s shoulder. They were both looking down at a child in a stroller; all three were laughing.

What had stirred Rulx was the sight of two men approaching the tableaux from behind. They were moving, not exactly stealthily but carefully. They had time and knew it. And as they approached their hands moved, first into their pockets then out. The man further away had a length of rope, a garrote; the closer one had a long, slender knife, a stiletto.

What happened next happened so quickly that even people who were watching could not say what they saw. With dizzying speed Rulx had dashed across the avenue and intervened himself between the men and the family, stopping in front of the rope-carrier and behind the Big Man with such abruptness that he might have been an electron jumping from one orbit to another. The assassin was stunned just long enough for Rulx to cross his own wrists, grab the man’s, uncross his own wrists, thus crossing the man’s, drop and spin so that the man now was choking himself with Rulx behind him. He very quickly brought the man to his knees, his face turning blue and tongue protruding as Rulx tightened the rope. The entire action lasted no more than four seconds.

As that was happening, the second man fell to ground with an agonized scream. Carfagna had run behind him, sliding on his right hip along the grass as he passed the man. Before he was entirely beyond his target, the man was on the ground. Carfagna, who had drawn his own knife as he dashed across the Diagonal, had sliced both Achilles tendons as he slid past them.

“Reynard!” Beatrix was radiant. “I thought they would send you! Thank you. Thank you thank you thank you!” And she embraced him with genuine fervor. “And thank you, Reynard’s friend,” and she pecked him on the cheek. The two men were smiling broadly; the Big Man was not. “Gentlemen,” said Beatrix, “I want you to meet my husband, Tommy Cosmo, and our daughter, Blanche. Come.”

So the four adults and the child in the stroller strolled back across the Diagonal, Beatrix with her arm through Rulx’s, Carfagna pushing the stroller as he jabbered to Blanche in Italian with Blanche jabbering back in pre-toddler, and Tommy Cosmo directly behind them all, calm now but watchful. No one in the street or in the park paid any attention to the wounded men on the ground, who seemed to be enjoying the unseasonable sun.

Once seated Cosmo said, “So, Trixie, these are the two men you’ve told me about?”

Carfagna, glancing at his friend, chuckled.

Trixie?

Within twenty minutes, the two friends learned that Tommy was a Recon Marine stationed at the American embassy on Avenida Wilson. He and Beatrix had met in the City of Como, very near Varenna, when Tommy was on leave while stationed in Germany. Apparently it was love at first sight. They’d been married three years, as long as Tommy had been in Peru; beautiful little Blanche was not quite two years old.

Then Rulx asked, “were you born in East Harlem?” and Carfagna asked, “which of your parents is moreno?” Beatrix laughed from her belly. Tommy grinned. “I’ve never known my parents,” he said. “As an infant I was left in a box in the lobby of the Cosmo movie theatre on 114th Street, between Third and Lexington Avenues, yes in East Harlem. The nuns of a Catholic orphanage, St. Thomas Aquinas, raised me and gave me my name, after the saint and the theatre. At eighteen I joined the Marines. And now, fifteen years later, here we are. Is that enough for you both?”

He paused. Everyone paused, and Tommy added, “Giovanni”—by now the couple knew the name of this happy, handsome and capable friend—“why do you Sicilians all like the knife so much? Can I see what you cut him with?”

“Of course,” Giovanni answered, but did not take out the weapon. “And, not-so-by-the-way, I’m Abruzzese not Siciliano.”

“Whatever,” Tommy answered.

“Are you really a Marine,” asked Rulx. “It seems no Marine, least of all an elite Recon Marine, would be so insouciant about detail, or invent details as ridiculous as you have about your name.”

“Listen, Reynard the Fox”—and Reynard thought, another man who likes nicknames—“you can find out just how much a Marine I am the hard way—”

“Rulxy,” interrupted Carfagna, “I do think Sergeant Cosmo is put out that we had to save him and his family. It’s to be expected. You know how Americans like to be the hero. And by the way, I’ve never seen your hands move so fast.”

It was Tommy Cosmo’s turn to laugh from his belly. “Well, have we had enough banter, Vivi?”

Vivi!

All three men looked at Beatrix. Blanche was asleep. Everyone smiled but no one spoke.

Tommy Cosmo, however, had his limits. “Here is our purpose, Reynard, short and bitter. There is about to be a golpe del estado. Your old friend President Belaunde—I’ve heard the story more than once, believe me! —who is not quite at the end of his five-year term, is to be kidnapped, spirited off to Cuba, and . . . and never heard from again. We are here to alter that plan.”

Beatrix picked up the thread. “Those men you disabled must have been sent to stop us; Peruvian muggers don’t arm themselves that way, and none, I believe, would think to take on a man Tommy’s size. As far as they know I’m nothing more than his socialite wife.” She sighed. “We were surprised. We simply did not know that they knew of our intelligence. You saved our lives, Reynard, Giovanni.”

“And certainly Blanche’s as well,” added Tommy. “Really, there are no words. . . .” He hugged each man warmly. “Right now we should all go along to our home.”

Rulx looked directly at Tommy Cosmo. He said, “you know I’m in love with your wife.”

Cosmo did not hesitate. “Of course. Vivi and I have no secrets. But it has been, what? five years? And I assume you know you’re one of a long line of men? All standing behind me.”

Rulx held the Cosmo’s eyes; Cosmo stared back.

“Big Man,” said Beatrix, “you are the light of my life. Beyond that is dusk.” The husband and wife kissed, with tenderness and, clearly, with a restrained passion. Then Beatrix said, “Reynard, your old friend Lola sends her love. She’s still single, you know.”

Giovanni jumped in, saying, “shall we be on our way?”

This time the family went ahead together as the two friends, shoulder-to-shoulder, trailed, relaxed certainly, but alert.

“Rulxy, I’m sorry. I know how you’ve hoped, all these years . . . “

“I have, Gio”—Rulx’s most affectionate form of addressing his dearest friend—“but you see how happy she is. I tell you truly the sight of that brings me joy.”

“Oh, I’m sure it does, Rulxy. You would not be you if it didn’t. But there is something else to be happy about.”

“Well, the little girl . . .”

“Yes. That little Blanche. I believe she already babbles in Italian!”

And Carfagna threw his arm about his friend’s shoulder and squeezed him, as though awarding a laurel.

The Cosmos lived in a large, detached (becoming rare in Peru), two-story Spanish Colonial house on the corner of the first street within San Isidro on the Avenida Arequipa, a long boulevard divided by trees for its entire length, which runs for three miles from Larco in Miraflores to Avenida Wilson, the site of the American embassy.

Once inside and very comfortable, with port in hand, Rulx toasted the couple on their marriage and on their daughter. Carfagna asked if the tale of Tommy’s name were true and was assured that, indeed, it was. Rulx actually chuckled.

When Tommy allowed that the fit between him and the Institute was perfect, Rulx merely nodded. “It’s mission is my mission, Tommy.”

“But,” said the Big Man, “weren’t you shocked to learn exactly what sort of Institute Beatrix had recruited you into?”

“More like dazzled,” he answered, “rather like finding yourself in a labyrinth that leads to more and ever greater adventures of mind, action, and gratifying accomplishment. In truth it seems like a richer and more ample version of the life my parents led during the War.”

Beatrix smiled benevolently. “Now we are in Peru, and the life of the Republic, not to mention that of Reynard’s old friend, is at stake. We cannot save the first, but if we save the man then the Republic, one day, will be restored. Here is what we know and what we must do.”

The golpe proper could not be prevented: the palace guard were of the golpista party, and Colonel Velasco, inexplicably charismatic and spouting the usual revolutionary indulgences, was situated immediately to replace Belaunde. Since all branches of the military were in on the plot, resisting in Lima would be impossible.

“On the ground,” Beatrix continued, “the president will be in the custody of six. A technical crew—that will be our people—will already be on the plane. Before the president is on the plane, we commandeer the craft from perhaps four men but no more than six. The pilot, though not the co-pilot, is ours.” Beatrix continued. “The original crew will be released. The pilot and our people, minus one, then will fly the plane to Florida. The golpistas will not know their Cuban plan has misfired until the plane overflies the island, by which time it will be too late.”

Carfagna asked, “How do our flight crew replace the real crew on the plane?”

“Any way necessary,” Tommy answered. “But our guys will be dressed like technicos servicing the plane, so surprise is with us.”

“And on the ground?” It was Carfagna. “Surely the president will be held by a squad of golpistas who will also escort him to the plan. How do we neutralize them and get control of the president?”

“One of our guys returns from the plane to the hanger. He takes out the escort detail, six men, then takes custody of the president and gets on the plane with him. And off they go.”

“The worst case,” Tommy breathed deeply, “is that the golpistas see through the ruse or resist. Taking the president is the decisive act; if they sense a trick they might panic. They might even kill him. Surprise is key. There is no room for a firefight.”

“Who are the guys who take the plane?” Carfagna asked.

“We’re here,” answered Tommy. “The three of us plus the pilot.”

“So,” said Rulx, almost in a whisper, “they have maybe six men inside the plane, six outside holding the president. And there are four of us. Let me guess, Cosmo. You’re the man who goes back to neutralize the golpista squad and take custody of the president.”

“That’s it.” Tommy, who had been standing all along, slouched against the wall and smiled.

“No. That is not a plan. And there can be no guns.” Rulx was clearly angry. Tommy stood away from the wall.

Carfagna broke in quickly, before Tommy could draw a breath. To Tommy he said, “I believe Rulxy has a plan. It took you a little longer than usual, no Roscoe?” He did not turn to his friend.

“I had to let Tommy finish, Carfang. My plan is to turn the escorting group on each other. Leave that to me. I’m the man who goes back.”

Tommy just watched, relaxed, and said, “You gonna hypnotize them, Mr. Magic?” Then, looking at Carfagna, who by now was close, said, “who’s playing the hero now?”

Beatrix asked, “how Reynard?” and Tommy looked at her.

“Will the president know we have a rescue operation?”

“No. We do know that the golpistas will tell him that he’s headed to Florida, to keep him relatively calm. Remember, this is a man who swam the Pacific from El Fronton prison to Callao after escaping and who actually fought a duel. He’s not beyond action of his own. Keep in mind that after the incident in the park the golpistas may be on very high alert.”

“Vivi, I’ll handle it . . . linguistically.”

Tommy was beyond himself. “Linguistically . . .”

“Leave it to me. I only need to know this: does the leader of the escort group have a wife or a mother or, preferably, both?”

4.

Twelve hours later Tommy, Carfagna and Rulx were technicos on the tarmac of Jorge Chavez International Airport, shuffling to the DC-4 that was everyone’s focus. Tommy was stooping and limping, for not many Peruvian laborers had his height, bulk and stride. When the three men got to the gangway, Rulx turned back, as though he had forgotten something. The other two climbed the stairs and disappeared into the cabin. Rulx returned to the airport building to meet the captors and the president.

Rulx played the part of a cholo, certainly bowing if not scraping, avoiding eye-contact. Then he looked directly at Belaunde. This was a delicate moment. He hoped for recognition, which would spark some surprise, and then a supposition—that some intervention, perhaps even a rescue, was afoot. But he also hoped for a poise that would reveal nothing.

“Excuse me, Mr. President.” All eyes turned towards Rulx.

“Yes. Mr. President indeed.” Belaunde looked at Rulx imperiously. “What do you want?”

“Excuse me, Sir, but I’ve been instructed to say to you and to all here that the bathroom facility onboard will not be operational until well into the flight. If anyone must use the servicio it is best to do so here, the sooner the better.”

Belaunde stared at Rulx, his face showing nothing. “Very well. I assume I must have company.” He turned and two of the six men, including the captain in command, turned with him, the three walking back into the hall of the building and turning to their left. Rulx was alone with four men. He waited, feet shuffling in place, head bowed. The sergeant looked at him.

“Chico, tell me, what do you hear?”

“Gossip only,” Rulx answered.

The men laughed, not without scorn. “Gossip?” said a corporal. “That’s all that interests you vermin?”

“Well,” Rulx answered slowly, “yes, if the gossip is good enough.”

“So spill it, cholo bruto. We need to pass the time.” The corporal was a swarthy man, and small, but he was feeling power for the first time.

“It is ugly. I shouldn’t. I heard it from the captain’s own maid.”

Now the sergeant was hooked. “Captain Chavin? Our captain?”

“Yes.”

“Well then. Let’s hear it. This could be official business.” The four soldiers chuckled.

“Very well. The maid heard the captain boasting to another captain. He said that yesterday he had fucked the wife of one of his men, one of the men in the ‘special group’ he said.”

“Lying piece of shit!” shouted the sergeant, slapping Rulx hard. Rulx reeled in place and rubbed his cheek, eyes down.

“What else!” the sergeant demanded. Rulx was silent, trembling faintly. “What else! You son of a whore. Everything! Now! Or you will not walk away!”

“Please sergeant, please. Don’t hit me again. Please.”

“Speak then, you maricon piece of shit.”

“The maid said that captain boasted of the woman . . . sucking him . . . y que se la cacho por el culo y que la gusto tanto que lo rogaba mas pinga y que lo haga mas duro.”

When the men heard that the woman had begged to be further sodomized, harder, and in the most vulgar terms . . . the silence was still and cold. It seemed to freeze the men, who just stared. Finally the sergeant spoke.

“Whose wife is this woman.” The sergeant spoke slowly and deliberately. When Rulx said nothing he repeated the question, but this time he drew his pistol slowly.

“Sergeant. I . . . I don’t know the name. The girl never said. I—”

The sergeant struck Rulx again.

“Please. Please sergeant. It is gossip only. Please—” Another blow.

“No more. No more,” Rulx whined. “She said . . . she said only that it was . . . it was . . . his sergeant’s wife.”

The stillness was stonelike. There was no sound, at first. Then, after perhaps five seconds, during which the sergeant might very well have pulled the trigger, the men heard steps approaching. The first man to turn the corner was the captain. The sergeant said, softly and simply, “first you, my captain, then your wife, and finally your mother.” He shot him between the eyes. The sound was deafening, and time stopped. Everyone seemed to stand still for a very long time.

In fact almost immediately the corporal and the other two man leaped on the sergeant, the man who was with the captain turned and, thinking he was in the midst of some sort of rescue and was therefore next, turned and fled, and Belaunde—instantly reading the scene and recognizing the opportunity—fled towards Rulx, whom he had indeed recognized. By the time the four scuffling soldiers noticed them, they were more than half way to the plane.

The corporal thought to pursue but wasn’t sure he should. The sergeant grabbed him. “Leave them. By all means, the puto is trying to make points and the president is completing our plan for us. We want him in the plane. Too bad we suffered a casualty.” And he looked at the men one-by-one. “Too bad,” said the corporal. “The captain was a good man.” “A patriot,” said another. “A martyr,” said the third.

Once on the plane Rulx beheld a nonsensical scene. Five men were on the floor, unmoving, either dead or unconscious. The pilot was in the cockpit at the controls. The sixth member of the original crew was standing against the bulkhead opposite the door, holding his right arm with his left and writhing in pain. Tommy was kneeling, cradling Carfagna in his arms, and staring up at Rulx. Carfagna was limp.

“What has happened here?” It was Belaunde who asked.

Rulx fixed Tommy’s eyes with his own.

Tommy, his eyes not leaving Rulx’s, said, “the man at the controls is Air Force, loyal to you, Mr. President.”

Belaunde looked at the pilot, who turned his head slightly, saying “mi presidente.”

“This man”—Tommy nodded at the writhing golpista—“this man . . . he got off a shot. Giovanni and I had dispatched two, our pilot one. He was turning on this man when the shot went off. He was aiming at the pilot but . . . but . . . well, Reynard, his aim was off. He hit Giovanni in the back.”

Rulx, assuming his friend was dead, bent to the floor, retrieved a lug wrench, slowly straightened himself, and before anyone knew what he was doing smashed it down on the wounded man’s skull. The smash of the blow and the cracking bone together were almost as loud as a gunshot. The man dropped. Rulx raised the weapon a second time, but the president grabbed his forearm.

“Please, Dr. Rulx. Please! The man is gone. You’ve finished him. Your friend needs—he needs attention.” Rulx looked at Belaunde with deadly eyes, then pivoted towards Tommy and Carfagna. He took two steps forward and knelt, whispering in his friend’s ear.

To the astonishment of both Tommy and the president, Carfagna nodded, once, very slowly, and whispered in Italian, “yes, please, my friend. Thank you.” Putting his hand on Carfagna’s head, Rulx, in a low, strong, steady voice said the Catholic Act of Contrition in Italian.

Oh mio Dio, mi spiace di cuore per aver offeso

E io detesto tutti i miei peccati a motivo della tua giusta punizione

Ma più di tutto, perché ho offeso te, oh mio Dio

Che sei tutto buono e degno di tutto il mio amore.

Sono fermamente risolvere con l’aiuto della tua grazia

Per confessare i miei peccati, a fare penitenza, a modificare la mia vita,

E per evitare le tentazioni del male.

Then, with exquisite tenderness, he took his friend’s body from Tommy.

The plane had been taxiing and was now stopped at the end of the runway, wrapped in absolute darkness. Tommy walked to the hatch and threw down the gangway. He saluted. The president saluted. Tommy then went to the co-pilot’s seat. Beatrix, who had been waiting below, climbed the gangway and entered the plane. Without a word Rulx, with his friend in his arms, descended the gangway. Beatrix stepped to her husband and kissed him passionately, then followed Rulx. Very soon the two, with Carfagna, disappeared into the black of night.

Two months later President Belaunde was at Harvard University. He had written to Beatrix in Peru, but she was already at the Villa Monastero, in Varenna, the home of the Institute, with Tommy and Rulx. They also had notes from Belaunde. All three were in Spanish; his gratitude was concrete, his condolences were deeply felt. He vowed that one day he would receive them at the presidential palace in the Plaza de Armas. As soon as they finished reading the notes they burned them.

And all along Reynard grieved, and as he grieved he longed, though many years would pass before he would know the object of that longing.

_________________________________

James Como is the author, most recently, of The Tongue is Also a Fire: Essays on Conversation, Rhetoric and the Transmission of Culture . . . and on C. S. Lewis (New English Review Press, 2015).

Please help support New English Review.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by James Como, please click here.