Tales of Rulx: Liberty and Death

by James Como (February 2018)

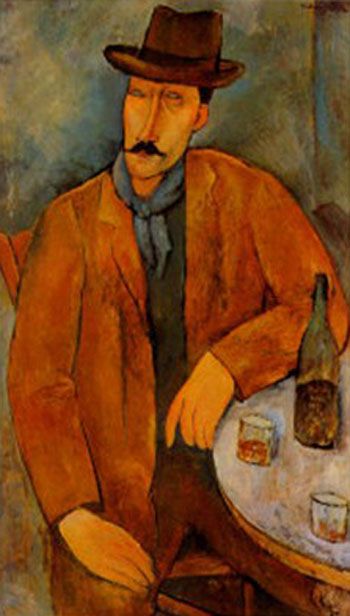

Man with Glass of Wine, Amadeo Modigliani, 1918

1981.

The city of Cajamarca lies in the North-Central region of Peru at an elevation of nine thousand feet. Amidst its dairy farms are gold mines and resorts, reconstituted haciendas that would soon become a different kind of gold mine. The land is dotted with forests and cut by streams, gulleys, rivers, low hills, and with dirt roads and city streets that rise and fall with the terrain. At a close distance are Andean peaks: along the foot hills tourists hike and horseback ride. Except when the noonday sun shines hot the weather is always chilly, especially when the wind gusts; it unsettles the cows.

The indigenous peoples, independent, remote but friendly, largely humorless, are descended from tribes conquered six hundred years ago by the Inca first, then by the Spaniard. Nearby are the terrorists, a sadistic group known as Sendero Luminoso, The Shining Path.

At a particular resort—Laguna Seca—a woman, hump-backed and one roll shy of obese, chugged as she waddled to the front desk, jabbering along the way, arms flailing for balance. The trapped clerk knew what to expect.

Once gasping at the counter she growled, “I told you. I needed the entire text of the Patrick Henry speech up, on the screen, not just ‘give me liberty or give me death’. Everybody knows that. It’s a tag line. What comes before that is my subject. It’s what gives the line its nobility.” She paused as she shook her head slowly. “Why the Liberty Society chose this speck of dust as a meeting place is unfathomable to me, but I certainly will not permit it to compromise my liberty!”

“Yes, madam. I’ll call our tech people immediately, madam.”

A dozen or so people trying but failing at discretion watched the exchange, all except the man who stood standing against a column at the far broad staircase. Pencil in hand, he was correcting the manuscript of his new book, a dictionary of Culle, a local language spoken by a few hundred tribespeople living in a nearby forest. He had spent three weeks there but had been able to transcribe only fifty words. It was a short book.

“And one more thing,” the woman shouted. “It’s happened again—don’t pretend not to know what the hell I’m talking about. And do not dare—do not dare!—tell me it’s my imagination!”

Short, skinny, clearly not long on the job, and now lamenting that he had displayed considerable mastery of idiomatic English, the poor clerk could only recite the woman’s complaint. “Yes madam. Objects in your room have been moved, small items stolen, nothing broken, windows and doors locked, no forced entry.”

“That’s right. Service personnel with access to the room. Unless you have ghosts. In any case, make them stop. Now. Do not make me take steps, young man.”

“No, madam. Yes, madam. I’ll visit your room again madam and see to it myself.” The woman waddled away, breathing heavily.

A handsome woman of a certain age, slender, tall, and elegantly dressed, approached the counter. “Don’t displease Bertha,” she told the boy. “We all know she’s half nuts. None of us wants to see her totally nuts, believe me.”

“Yes madam. I will do so. I will not do so.” At that the woman grinned so winningly as to save the clerk’s morning and turned towards the staircase. As she was passing the man standing alone, he spoke.

“Pardon me. My name is Reynard Rulx. Would you mind a question?”

Uber-poised, the woman stopped and stared at the man, her right eyebrow raised into a steeple. Though neither handsome nor tall, Rulx was groomed meticulously and expensively dressed. Women found him attractive, which he rarely noticed, though he did like one woman’s comparison of him to Jean Paul Belmondo and, especially, another’s to James Cagney.

“Constance. And you mean a second question, surely. Why no sir, I would not.”

Rulx grinned and nodded. “Any chance you’re born and raised in or near Abilene, Texas?”

“Oh my,” Constance looked genuinely startled. “That is good. Really good. Yes, my daddy was in the Air Force and stationed nearby. Are you related to Henry Higgins?”

Rulx smiled broadly, recognizing the reference to the acoustic phonetician of Shaw’s Pygmalion.

“Yes, sort of. I’m a philologist,” actually a designation not heard for a hundred years.

“Of course you are. And . . . French? No, wait. Dutch.”

“Ah, no, never French. Born in Belgium but—”

“Flemish!”

“Yes. Now you are good. And—”

“Never French.”

“Never. Or Belgian.” Rulx looked comically grim. “Or Dutch, for that matter. But never French.”

Now it was the woman’s turn to smile. “Well,” she asked, “we won’t find any Flemish food here, nor any juleps, but I’m sure we could find something to enjoy—if you’re hungry and able to converse as you eat.”

“I certainly can, though it’s more like eating as I converse.”

“Oh dear,” she said, “this could be the start of a beautiful dinner.”

Once at table they spoke of all sorts of things, including mystery novels (they both especially red herrings) and movies but not the contretemps involving poor Bertha. Rulx had roasted cuy, a sort of guinea pig splayed on the plate that looks back at you as you as you dig in—a specialty of the province and of the house. Constance tried not to pay it any attention. As they were about to finish, she invited Rulx to join the Liberty Society hospitality hour.

Constance introduced Rulx into a clump of four: James, bearded, sixties; Ida, shapely and facially disfigured, likely from botched surgery, forties; Daisy, new to the group, brown, svelte, and the mother of five; Steve, trimmed beard, congenial, low key. The eight others only glanced at Rulx: his being with Constance was all they needed to see.

“Madame President,” said Ida. “Congratulations on your victory.” Constance had recently won election to office, with more than seventy per cent of the vote worldwide. At that, someone with a different scrum raised a glass. “Here’s to Constance!” shouted a big man, “with our thanks for being willing to serve!” “My privilege, Tim,” she responded. And the room chimed, “To Constance!” Rulx murmured “congratulations,” as he looked into her eyes. He was pleased that she had not told him of her triumph.

What she had told him is that the Liberty Society has branches in eighty countries, that it conducts two hundred seminars throughout the world each year, and that its purpose is to spread the concept, as Constance quoted, of “liberty without license.”

“Constance.” Rulx, stepping in, was almost whispering. “Why is Bertha not here?”

“Oh, she’s just silly, that’s why. This is the hospitality hour and she is utterly inhospitable. Besides, she’s preparing her Patrick Henry seminar tomorrow. Like her hero she’s something of a perfectionist. She’ll be up till all hours, but it pays off. She really is marvelous at what she does.”

“Which is?”

“Stylistics. She has a real talent for breaking down the written form of a text and re-connecting the parts to a theme.”

“Ah. Very like philology. Let’s see. She’ll discuss the driving, varied rhythms of Henry’s sentences, the cumulative power of the diverse figures of speech when strung together, and then show how freedom, too, has a rhythm, one that death lacks of course. Thus ‘liberty or death’, the rhythms of freedom or the stillness of death—both preferable to the de-humanizing stagnation of tyranny. I’ll not want to miss that.”

Constance was open-mouthed. Rulx was pondering.

“Reynard, did you improvise that?”

“Not exactly,” Rulx answered matter-of-factly. “My parents fought in the Resistance. They believe the Henry speech inspiring and taught me and my three brothers to see it that way; rather, to feel it that way. We memorized it.”

“Reynard, who the hell are you and what in the world are you doing here?

“I told you. Studying Culle.”

“No, you hadn’t.”

“Really? Well, so I am. It’s little spoken and even less well-known. Also, I’m here to meet an old friend in his new house.”

“Here in Cajarmarca?”

“No. In Lima.”

“So you know Peru well then.”

“My professional life began here.”

“Indeed. Do tell more.”

Now Rulx was smiling broadly. “Constance, would you walk with me a spell? The chill is refreshing and the small zoo by the stables is lighted. There are alpaca, regional rodents, horses, cows, and a peacock. Some of the cows actually come when called by name.” As he spoke he offered his right arm, which Constance took in her left, and out they strolled.

They walked along the broad dirt road away from the lobby, away from the attached cottages (each with its own sunken thermal bath), away from the dining room to their left, from the spa to their right. The tree-hung lamps became fewer, the wind rising, the lawns on either side heavier with waving grass and thick brush, the bridges crossing the thermal creeks more frequent, the vapors thick and swirling.

“Cajamarca mattered greatly to the Inca, who, by the way, were not noble savages.” Rulx was in his didactic mode. Constance could only nod.

“The Inca himself would bathe in the thermal waters here, which is why, according to some historians, the conquistadores found him close to this very spot. The story of Atahualpa’s ransom is well-known, and distorted. He never did fill the room with gold to the height of his raised arm. When he proved too smart for his own good, Pizarro assassinated him. The real shame is the slaughter that took place in the city square, thousands dead, all owing to a simple mistranslation. A damnable mistranslation. The day after tomorrow is July 26th, the anniversary of Atahualpa’s death, a holiday in Cajamarca.”

“Imagine that,” Constance chirped.

“Would you like to know why Atahualpa’s hair was so long?”

“Why, yes I certainly would!” She knew that once a man gets to talking about something he knows it’s best to keep him going. Many women never learned that, she thought, or these days didn’t care.

Then, just as they were about to arrive at the zoo and Rulx was about to explain why Atahualpa had long hair when no other male Inca did, a long, grotesque howl ripped apart the night itself—and and its mood.

With a shared glance but without a word, they turned and bolted for the cottages. Rulx, who was very quick, slowed enough for Constance to keep up. To his delight he saw that she was no slouch.

At her cottage, Bertha was still screaming. Constance said, “enough,” and Bertha stopped screaming, just like that. Rulx was impressed. They were outside, surrounded now by everyone from the Liberty Society and a by handful of resort employees, including the staff boss, a large, imposing woman of indigenous stock. On the ground, lying on his stomach with his face in profile against a wide pool of blood, was the young clerk.

“Someone call the police.” It was Ida. “We must stay together!” She was trembling.

Another Club member—Tim, the big man who had shouted his congratulations—said, “very well. How long will it be before they arrive?” He was trying hard to demonstrate some command.

“Maybe an hour,” Rulx said, “in my experience. I’ll make the call.”

Constance looked at Rulx almost imploringly. “Certainly not much longer than that, I hope,” and Rulx nodded.

Staring at the two of them, Tim muttered, “I see.” James covered the dead man with his own jacket and said softly, “we really ought to stay together.” The group, chattering nervously in a bunch, returned to the hospitality room, followed by the staff. No one thought to pary. Daisy stayed behind with Bertha, Constance and Rulx, and one staff member, the large boss woman.

Constance turned to Bertha, who was sobbing. “Bertha, what happened?”

Daisy coddled her, led her into the room, and sat her down on the bed.

But the boss lady spoke with disdain to Rulx. She used rude and uncommon words—sarapastroza (‘messy’) and charcheroza (‘disheveled’)—about Bertha. She did not hide her suspicion. Rulx, ordinarily polite to the point of courtliness, now answered rudely. He called the boss descuageringado (‘slobbish’). She stared in amazement that a gringo should know such words. With a disgusted glance at Bertha the boss left.

When Rulx entered the room, Bertha was sniffling. Constance was on her left, Daisy on her right. Rulx, in a deep knee-bend, was in front of her. He took her hand. Bertha looked at him, saw him smile, and smiled back. “Please, Bertha, tell us what you know. There is no danger now.”

Bertha inhaled convulsively. She looked fixedly into Rulx’s eyes. Then she asked in a raspy whisper, “Who are you?”

In that instant Rulx saw in Bertha’s sustained gaze a crystal clarity of mind and a will of shining gun-metal blue. As she returned his gaze he answered, “my name is Reynard Rulx.” He paused. “An independent scholar here to study a local language. Now I am a friend of Constance’s.”

Constance added, “we were walking at the stables when we heard your scream, Bertha. That’s when we ran to you.”

All the while Bertha had not taken her eyes off Rulx’s own, nor would she as she spoke. But she did take her hand from his to grasp Daisy’s.

“I was preparing my lecture for tomorrow, groundbreaking ideas, Patrick Henry . . . ”

“What happened then, dear?” asked Constance.

“I heard scuffling, muffled speech, right outside my door. At first it seemed in the background but soon I knew it was close. I’ve been so uneasy, frightened even. But they wouldn’t do anything. Finally I opened the door and—and—you know the rest. There was that boy, in his own blood. Smashed.”

Rulx stood, looked at Constance and Daisy, then looking back at Bertha he asked, “and that’s when you screamed?” He waited, watching her as she looked back at him, her eyes bright, and then broke the silence. “Of course you did. Perhaps no more prep this evening, Bertha? Sleep will make you even sharper for your presentation. By the way, would you mind if I attended?”

Bertha beamed. “Oh no. Certainly not. Please do. But . . . the murderer—”

Daisy interrupted. “Bertha, I will stay with you. I have nothing tomorrow but to enjoy your paper.”

With that Rulx moved to the door, expecting Constance to be behind him. But she was still looking at Bertha. “Constance,” Bertha said as she blew her nose, “you have much work to do. I’ll be fine.” With that, Constance patted Bertha’s hand and followed Rulx.

Once outside with the door shut behind them Rulx, softly, said, “let’s take a look at the body before the police get here.”

“Is that wise?” asked Constance. “A crime scene and all? Evidence?”

“There is one item we must check, only one.” He removed James’s jacket. “Look. What do you see?”

Constance stiffened. “A dead man in profile.” Her voice was like coarse sandpaper on rough wood. “His head in a pool of viscous, darkening blood.”

“That’s right.” Rulx bent and slowly, with some effort, pulled the head away from the clotted blood. “Look at the underside of his head, Constance. Tell me what you see.”

Bending close to Rulx, her face resting on his arm, she looked and said nothing. Instead she grasped her mouth and bolted upright.

“What?”

Gathering herself, Constance said, “a hole, a crater in his skull.”

“Yes. Now we call the police.”

Rulx re-placed James’s jacket and made the call. They walked towards the lobby. No more than thirty minutes had passed since Bertha’s scream.

“And Bertha? Is she safe?”

“Safety is relative, Constance.”

They walked to Reception. He told the staff they would be questioned by the police, but he pointed to one—“Chimba (‘big head’, vaguely derogatory), you come with me.” The man, short but indeed with a huge head, stepped lively, almost happy to have been chosen by such a commanding gringo. “The rest of you should go about your business until the police arrive.”

Once outside with Big Head, Rulx spoke quietly. “I have an instruction. If you see or hear anything at all suspicious—especially among the gringos and that big boss—report it to me at once.” The man nodded and they parted.

Rulx sat with Constance among the Club members. They were spread out, so a soft-spoken conversation was possible.

“The time has come, Reynard. My questions.”

In a short time Rulx had become attracted to Constance, who sensed this, as he did hers to him. “Do you know the Institute for the Study of Culture and Conflict? A think tank, at the Villa Monastero, in Varenna, on the eastern shore of Lake Como.”

“Never heard of it.” Constance turned her body away.

“Few have. There I am a Professor and Senior Fellow.”

“At a think tank.” Constance did not care to mask her skepticism.

“We are supra-national; broadly speaking we share your goals.”

Constance stared straight ahead, her poise no longer so uber. “Why are you here?”

“We know of the work of the Club, of course, and of its great value, of its high repute internationally. And we know of your personal value to ‘Liberty without License.’ You are consequential. You are also a valuable symbol. Now there are ideologues who also know what we know who want to stop your work—and you. They walk the earth in many guises but act as one, like people unknown to each other at a stadium who rise and cheer as one for a goal.”

“Oh, Reynard. Reynard Reynard. You, a tiresome conspiracy theorist? That’s why you are here?”

Rulx could not say that he was here at the instruction of the friend whom he would be visiting in Lima, in fact the President of the Republic, Fernando Belaunde Terry, whom Rulx had first met in 1962 and whose life he had helped save in 1968.

Instead he snapped, “Constance, you know better,” and Constance felt a frisson.

“Two days ago, The Shining Path captured a woman who had formed a milk collective. They tied her up, attached dynamite to her body, and took her to the town square, where she was surrounded by the villagers, including her children. Then they blew her up. Do you see? The only path permitted is Sendero Luminoso, The Shining Path. As for me, I am studying Culle. And I would protect you.”

Constance turned back and stared into Rulx’s hazel eyes, at once smitten, incredulous, frightened.

“I see. Protect me. From whom?”

“From ideologues who would kill you.”

“And you would stop them?”

“Yes.”

“Killing him, or her, or them? Person or persons whose identities you do not know?”

“Maybe.”

“On behalf of a think tank.” She paused. “Have you done this before?”

“On behalf of freedom without license. And, yes, I’ve been a soldier and have known combat, like many others.” Rulx would not say the whole truth, that in saving the president’s life he had crushed a man’s skull by a single blow with a wrench.

“And when you do act, however you act, will it be with absolute certainty?”

“Absolute.”

“Well then, in that case—detect. Maybe you’ll catch an actual murderer, the actual murderer. And—and I haven’t had dessert. Do I go about my business as usual?”

“Exactly.”

Constance waited a beat or two. “So, tell me more about your institute.”

“Not tonight. Too boring.”

“I’ll bet.”

So they walked together to the lobby in silence, arm in arm.

The police were uncharacteristically thorough. Interviews, forensic gathering, the compilation of files on all present, a background of the group as a whole, Bertha’s complaint at the desk, the young man’s response and promise, Bertha’s scream and what she had heard, the arrival at the scene of everyone, the calming of Bertha. They concluded that the victim was struck from behind on the right side of his head by a right-handed person. (“Quelle surprise,” thought Rulx.) They searched several rooms and the environs and found nothing that could have been a murder weapon.

With that they seemed satisfied, so, after some three hours, the sergeant consulted by phone with his captain and concluded that the assault was the act of a person or persons unknown and would be further investigated in the following days. He arrested no one. They loaded the body and left.

“No arrest. Does not bode well, you’d agree?” It was Ida, who had been lurking.

Rulx looked at her.

“No, it does not.” He turned to Constance, seeking, without quite knowing it, a refuge in her lovely face.

“Dessert?” she asked.

“Oh yes. Let’s meet at that same table—in five?

“In five. I’ll powder my nose.” Ida was left standing alone.

Rulx headed for the men’s room, but Big Head intercepted him.

“Sir, you must know the staff are getting angry. One of them is murdered, none of them did it, no one is arrested. Do these gringos get away with murder? That is the question they are asking.”

“Promise them the killer will pay dearly. This will not be ‘murder by everyone and no one.’”

Big Head brightened. “Ah, Fuenteovejuna, Lope de Vega, the Spanish Shakespeare, so-called,

though we consider Will the English Lope.”

It was Rulx’s turn to brighten. The men nodded to each other and Rulx went off to the men’s room.

Once seated Constance asked again, “who the hell are you?”

Rulx answered, “My parents’ son, especially my mother’s. She was and is resolute, as we must be. The great Solzhenitsyn has taught us, Constance, that one way to commit evil is not to think. Willed ignorance, as he calls it, is the ruin of a human being. It’s what gives us ideology, a substitute for thinking. It makes possible a delight in cruelty and destruction. To do mass evil you must believe it’s good. Ideology supplies that conviction. The only measure of an ideologue’s morality is effectiveness. Look at Sendero, admirers of Pol Pot.”

Constance answered. “The Russian also said, ‘the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.’”

“I’ll let others worry about Original Sin. Here and now what concerns me is my effectiveness.”

“They can overlap, Reynard. The two—sin and ideology—can share in evil.” They were silent. Then, “are you resolute, Reynard?”

“Always one click more than the enemy.”

“Reynard, I’m old enough to be on friendly terms with improbabilities, like commando scholars—“

“Soldier-scholar. And diplomat. Not all that uncommon you know.”

“I’m tired, and tomorrow, after lunch, I have some remarks to make. You know, congratulate Bertha, who, believe me, will deliver, and thank Tim for choosing this lovely location and making all the arrangements—that sort of thing.”

Just then Big Head signaled to Rulx, who excused himself.

“There was a phone conversation, sir. The boss lady. Individual words. ‘Threat’, ‘tonight’, ‘both’ in that order—but that last was spoken as a question—then ‘both yes’—those were together.”

When Rulx returned—he had been gone no more than two minutes—Constance was rising to leave.

“Still no dessert,” Reynard said.

“Yet one more thing to look forward to.” And with that she smiled and wafted away, Reynard gazing after her. Then he dashed to her.

“You must not be alone,” he said when he caught her. “You are in real danger.”

“Oh? And what little thing do you suggest?”

Rulx hesitated, then said, “some theater of our own, and that you trust me, and that you play along with me. Will you do that?”

Constance tilted her head to the right, looked into Reynard’s’ earnest eyes, grinned oh-so-slightly, and nodded.

“When I say angrily, ‘so I’ll see the alpaca alone’, you say, just as angrily and loudly, ‘completely alone’, sternly.”

“Oh my. And sternly. I can do that. What’s one more improbability. And strike you.”

“Strike me, sure, if you think it works. Then storm off to your room.”

“Oh, it will work. Certainly for me it will work.”

Then Reynard said loudly, “fine then. I’ll see the alpaca alone,” and Constance said her line, with as much smugness as sternness, and stared, but without striking. With that he glared, turned, and stormed out in the direction of the zoo, and Constance did the same toward her cottage far to the right, smiling with self-satisfaction. The chill was bracing, the constellations bright in the Southern winter sky. Wind ruffled the branches. For fifty yards Reynard walked briskly on the path, crunching the gravel on his way to the stables then, very suddenly, like a man avoiding a speeding truck, darted to his right and sprinted towards the path leading to Constance’s cottage. He skirted the pond, leapt over the stone monument, and zig-zagged past the poles and trees with their dim lamps. He ran through the steam rising from the thermal wells used by the Inca. He was at his most feline.

Once at the path he trotted parallel with it in the dark until he saw the cottage. There he stopped and dropped to the ground. If you knew where to look and what to look for you still would not have seen him.

Within moments he heard speech, indistinct at first. Two women. He could not make out sentences but a few words carried on the breeze: su, vru, cani, chucuall. They were speaking Culle! ‘Sun’, ‘tree’, ‘sister’, ‘heart’. The low voices sounded like song, the words drawn out, the pauses brief, the exchanges warm. To Rulx it seemed romantic.

As they passed him Reynard rose behind them. For a few paces he followed silently until he was close. When within arm’s length he whispered, “ya se acabo el guiso” (“no more mush”). They stopped before turning, and Rulx wrapped an arm around the neck of each and squeezed. They squirmed as they choked, but the dark cloud of asphyxia grew until they dropped, unconscious. The boss lady and Bertha lay in a heap.

The kitchen mallet, the murder weapon to be used a second time, had dropped from Bertha’s hand. When Reynard turned he saw a frozen Constance staring at him.

“They were on their way to kill you, and they’re not acting alone. But they won’t be out long so we need help. Run to the dining room. Have Ramiro—Big Head—bring his two cousins and plenty of twine. Then stay there, be your usual collected self in the group. No theater.”

“That was uncalled for,” Constance answered, but thought, “Ramiro? His cousins?”

Within minutes the women had been bound, gagged, and dragged into the darkness, the mallet secured.

“Que tal intringuli,” Ramiro proclaimed, a rarely-used word meaning a complex intrigue. Showing off for the philologist, he seemed to be enjoying himself. The cousins stayed with the women.

Reynard instructed Ramiro to return to Constance in the dining room and to not leave her side. Then he sprinted to the zoo, approaching silently when he was near. He clambered to the roof of the stable like a chimp. From there he spied Tim and Ida watching from the shadows and, from his own darkness, “have I kept you waiting?” he murmured, as he dropped to the ground.

They had looked up. Reynard, now behind them, snapped Tim’s neck with a single twist. While the corpse dangled from his arms, Ida, understanding her helplessness, threw up her hands. “I surrender” she said calmly.

Reynard threw down the body like a filthy rag. “Ah. You surrender. Well, whether a revolutionary wannabe or a True Believer—it doesn’t matter. Some evil is unredeemable. Besides, You should be happy. You’ll be seen as a martyr to the cause instead of one of Lenin’s useful idiots.” When she turned to run Reynard sprang and applied his choke hold, this time long enough to finish her off. By then one of the cousins had arrived with two trusted friends. Ramiro had sent them.

After a long wait, with no one back at reception or in the dining room knowing any the better what had happened, the police arrived. Ramiro explained to them that an attempt had been made on the life of the president of the Liberty Club by the old gringa and the boss, that the gringa had killed the boy, as the blood and prints on the mallet would show, and that “the staff” had prevented more mayhem by defending themselves against those two who would have killed “hasta los animales”—“even the animals”—as a symbolic expression of anger. Unfortunately, they had fought hard and so the struggle got out of hand. Now the police could arrest the two women, claim to have prevented a murder plot, describe how they had protected the helpless animals, and get commendations and, maybe, promotions. They wrapped things up quickly.

As Ramiro was serving the flan—after all, he was being paid to wait tables—Constance asked Rulx why he had acted when he did. Reynard looked at Big Head and nodded. Ramiro explained. “I overheard one half of a conversation between the big lady and someone else. I told this to Little Head”—he nodded to Rulx, who smiled—“who did the math: act now.”

Rulx reminded Constance that the anniversary of the assassination of Atahualpa would be a perfect day for a political statement.

“Movement cadres are pulling down statues of Spaniards, of white historical figures. A general uprising is their objective. They are an offshoot of The Shining Path.” A deep silence followed.

“But what about the boy?” Constance’s gaze was distant, tears rolling down her cheeks. Rulx put his hands on her shoulders. “Reynard, I . . . Bertha?”

“The revolutionary underground has cells everywhere, as you must know. In fact it was Bertha, with Tim and Ida, who recruited the boss lady. As for the signs pointing to Bertha. She could have claimed, but did not, that the boy menaced her, that she therefore acted in self-defense. Instead she posits the implausible. That a common murderer would target that poor boy. She didn’t even bother to blame Sendero. Then there is the blood—its very dark color and wide pooling, as well as the boy’s hair already stuck to the clots: the murder had taken place at least ten minutes before Bertha screamed. Time enough for the boss lady to get there, take the mallet, and skulk away.”

Constance was shaking, though with what she wasn’t sure.

“They wanted a murder mystery to distract everyone from the real plot, the one to murder you. In other words, the boy’s murder was the red herring. Here we’ve had their theater. All Bertha’s nonsense at the desk, a charade. Bertha disturbing her own room. She knew he would check the room. Just so, the boy’s death, both a distraction and a lesson to indigenes who resisted, which the boss lady would proclaim once you were dead.”

“Is that it? A bloody distraction? Why? Why the boy?”

“Constance.” Rulx took her hands to his own chest. “The Berthas of the world would ask, ‘why not?’ Murder was Stalin’s solution, and Pol Pot’s, and Hitler’s, and that psychotic Guevara’s, and The Shining Path’s. Revolutionary movements reverse the order of things. For there are no human beings, only an abstraction called ‘The People,’ and that abstraction serves the Cause, instead of the opposite. But—and here is the most deeply disturbing human factor—Bertha couldn’t wait. When the boy showed up to do his job she was so intensely immersed in her Henry paper that she became . . . piqued . . . there is no other word . . . over the projection error, so she killed him as he stood at the door, impulsively, with the kitchen mallet the boss lady had given to her.”

“Personal pique?” Ramiro had walked away.

“We both know that evil and ideology do not exclude crazy. Did you not say ‘totally nuts’?”

“But you knew so early?”

“Oh. That I saw in her eyes.”

“In her eyes? And that was enough for you.” A statement, not a question.

“Well, windows on the soul and all that. Moreover, by looking back into mine Bertha could tell that I knew.”

Constance’s own eyes now were like the thermal steam outside. Reynard could not guess what she was thinking.

“You’re an assassin, Reynard. Pure and simple. A killer. From a think tank? I don’t believe that for a moment. Why not tell me the truth?”

Rulx looked into her eyes and she saw his resignation, a sadness tinged with truth.

“My friend—”

“Whom you will visit.”

“Yes. President Belaunde asked me to intervene. Certain intelligence had indicated an attempt here, on you, in coordination with your meeting and with the holiday and in the service of Sendero.

“And a provincial waiter with such fluent English?”

“Ah. Ramiro is that certain intelligence. One of Belaunde’s agents. He’s been here for weeks. His Russian is even better than his English. Shall we enjoy the flan?”

Constance shook her head. “Let’s skip the flan. Do you have any other post-prandial ideas?”

“None. I’ll be leaving tonight.”

Constance hid her disappointment.

“Oh no you certainly will not. I have work for you, my friend.”

“Constance, I—

“Look into my eyes, Reynard. What do you see?

“Constance . . .”

“Oh no. Not that, alas. What you should be seeing is this: You will be delivering Bertha’s Patrick Henry argument tomorrow.”

Reynard laughed from his belly. “Liberty or Death.”

“No. She billed it as Liberty and Death, and so it is.”

“Isn’t it always. And one more thing. ‘Victory is never permanent.’ Churchill.”

“Good evening, Reynard, and thank you for your . . . for your friendship.”

She kissed him tenderly and lingeringly on his slightly parted lips, and sashayed away. And he became happier than he had been in a long time.

Mid-morning the next day she told her people of an ideologically-motivated plot by The Shining Path that included Bertha, Tim and Ida, of the heroism of the staff in preventing Tim and Ida from killing animals and how the staff fought them, and of the quickness of the police in preventing her death. Nothing about Rulx or of Ramiro as his confederate.

When Constance had asked Rulx why he had not killed the two women he answered that, whereas Tim and Ida had tried to kill him, the women had killed a Peruvian and Peru deserved to send them to its prison, Lurigancho—a penalty worse than death.

She led the applause following Rulx’s presentation. In her response she thanked him, “a world-class oratorical philologist.” (Rulx bowed his head, not out of humility but to hide his grin, there being no such thing as an “oratorical philologist”.) Then she toasted Atahualpa, “the sorry but noble victim of the greed of the Conquistadores.” The wait staff cheered and applauded wildly.

Soon after, Ramiro asked to speak privately with Constance. He told her that Reynard’s friend’s “new house” was the presidential palace, but that the first reason for Reynard returning to Lima so hastily was to see “the love of his life,” as Ramiro put it, one Lola, whom he had first met nearly twenty years earlier.

By then the taxi had arrived. The wind was whipping, and there was no need for any other goodbyes. Reynard and Ramiro stepped into it and went on their way.

Just then Constance decided that next time the Club convened it would be in Varenna. She thought, “Lola, eh? Of course. Lola.”

Meanwhile the Sendero were running rampant in the highlands, though less so in Cajamarca than might have been the case.

_________________________________

James Como is the author, most recently, of The Tongue is Also a Fire: Essays on Conversation, Rhetoric and the Transmission of Culture . . . and on C. S. Lewis (New English Review Press, 2015).

Please help support New English Review.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by James Como, please click here.