Telling Tales Out of Public School

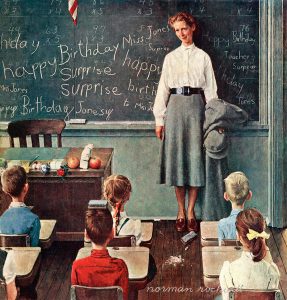

Happy Birthday Miss Jones by Norman Rockwell, 1956

by Jeff Plude (February 2022)

John Taylor Gatto fell into a career as a copywriter on Madison Avenue in the heady David Ogilvy-Madmen days. He says he did about the equivalent of one day’s work in a whole month, the rest of the time being consumed by power breakfasts, martinis at lunch, and parties after work. He was making big money. But there was no joy in his job.

One day Gatto declared to the copy chief that he was leaving, and was promptly offered more money, since it was assumed that he was jumping ship to another agency. But when Gatto told him that he was going to teach junior high, the copy chief said to tell his mother she raised a moron.

Gatto started substituting in Manhattan schools. It was 1964, and he was almost thirty. He taught in the area of his alma mater, Columbia, to Lincoln Center and from Harlem to the South Bronx. He was already burned out—chair-wielding students, administrators laying down the law, etc. He was just about to head back to copywriting, to eat his words that the copy chief had spewed back in his face. Though he noticed even when he was still at the agency that there weren’t any fiftyish copywriters in the hack stable.

Then along came little Milagros, a student in a reading class for “dummies,” as Gatto put it plainly. He was sitting at his desk listening to the Hispanic kids, third-graders, stumbling to connect three or four words as they took turns reading aloud. Except for Milagros. She read perfectly for two whole pages (“The Devil and Daniel Webster”)! What was she doing in this class?

She told him that her mother had tried to get her transferred to an advanced class; after all, she could read her brother’s sixth-grade English book. But the principal had refused. Gatto became her self-appointed champion, and set the stage of what would be a recurring but frustrating role: battling the gate-keeping self-serving administrators of what passes for American elementary and secondary public education.

Gatto went to the principal. She told him basically to mind his own business and get lost, but reluctantly agreed to test the girl. And Milagros performed beautifully, and was given what must’ve seemed like the Academy Award: she was finally promoted to the class she would’ve been in from the get-go if there’d been anyone in charge who cared an iota about the education of children.

His short run as pedagogical Galahad over, Gatto prepared for the inevitable return to writing snappy thirty-second commercials that sold the American dream in all shapes, sizes, and colors. But one day when he was subbing at the same school, his pint-sized protégé visited him and gave him a sealed envelope. Inside was a birthday card with gaudy blue flowers on it—and the words that sealed his destiny: “A teacher like you cannot be found. Signed. Your student, Milagros.”

It’s a heartrending sentimental story, and the bait that kept him in the teacher trap for the next two and a half decades. In 1991 he was named New York State Teacher of the Year (after winning New York City Teacher of the Year three times), and immediately wrote his resignation letter—a speech that became the first chapter in Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. The book, really a pamphlet-length collection of five essays, was published in 1992, the year after his retirement.

Gatto died in 2018, and I’m sure he was shaking his weary head and raising his forceful voice till the end. What made him unique was that his observations were dispatches from behind enemy lines. He also wrote a much longer book called The Underground History of American Education, which was published in 2001, but Dumbing Us Down is his manifesto.

Thirty years later, in light of Gatto’s thesis, the only thing to be surprised about the public school system in America are the particulars, not the conclusion. Now there are more reasons than ever for parents to not send their kids to the juvenile “prison,” as he calls it—Critical Race Theory, Covid lockouts, mask mandates, gender-sexual grooming, school boards and a secretary of education who slander and threaten parents who have the courage and the love to speak up about how their children are being mistaught, stigmatizing them as terrorists. A decade ago there was the disastrous Common Core of national standards. And there’s always the teachers’ unions, which are as antichild and antifamily as Planned Parenthood.

But it wasn’t always like this in America, Gatto tells us.

For nearly the first century of the United States’ existence, he says, the government didn’t force children to go to school. According to Dumbing Us Down, public school for kids didn’t become compulsory in the republic until about 1850, in Massachusetts. Three decades later the parents of Barnstable, near Plymouth, were the last to resist by brandishing rifles (I guess the last of that old Mayflower spirit was still burning).

A couple of decades later, in 1897, the major influence on the evolution of American public schools in the twentieth century wrote his first book on education. John Dewey spent the next four decades writing about how to educate the masses. He advocated for teacher training to be standardized in colleges and that teachers become professionalized, i.e., certified—something Gatto is dead set against. In fact he sees it as a major part of the problem. Anybody can teach, he says, and in fact they often do without even realizing it.

The conventional conservative wisdom is that with the growing liberal dominance in society in the sixties, American public schools have been in decline; that era did, however, give us mass entertainment in the form of a burgeoning television industry, which Gatto sees as additional brainwashing. But Gatto claims the school system was never not in decline. He says that Thomas Briggs, in the Inglis Lecture at Harvard in 1930, declared that “the nation’s great investment in secondary education has shown no respectable achievement.” Two decades later, in 1951, the situation was far from better: of 30,000 eighth-graders surveyed in LA, three-quarters (22,500) couldn’t find the Atlantic Ocean on a map! And over half of them couldn’t calculate what 50 percent of 36 is!

So Gatto maintains that American public education was diseased from its ill-conceived birth. He says it grew out of a desire in the mid-nineteenth century for more centralization and control of the population, or “social engineering,” which is antithetical to democracy. For that reason, he declares, the public schools are unreformable. “Government monopoly schools,” as he calls them, greatly harm kids, families, communities, and ultimately all of society.

This is obvious, he seems to say, unless you’re one of the legions who derive their power and profit from the system, i.e., educational administrators and the horde of experts and consultants. Gatto views them as nothing but “parasites.”

So how will kids learn what they need to know? Gatto points to a pre–Civil War, pre–public school America:

Before this development schooling wasn’t very important anywhere. We had it, but not too much of it, and only as much as an individual wanted. People learned to read, write, and do arithmetic just fine anyway; there are some studies that suggest literacy at the time of the American Revolution … was close to total. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense sold 600,000 copies to a population of 3,000,000, of whom twenty percent were slaves and fifty percent indentured servants.

Were the Colonists geniuses? No, the truth is that reading, writing, and arithmetic only take about one hundred hours to transmit as long as the audience is eager and willing to learn. The trick is to wait until someone asks and then move fast while the mood is on. Millions of people teach themselves these things—it really isn’t very hard. Pick up a fifth-grade math or rhetoric textbook from 1850 and you’ll see that the texts were pitched then on what would today be considered college level. The continuing cry for “basic skills” practice is a smoke screen behind which schools preempt the time of children for twelve years ….

Think of the “technology skills” supposedly needed for today. Many coders pride themselves on being self-taught, and played at programming in their youth as if it were Little League. And I’m pretty sure kids know how to use social media adeptly without any tutoring. Even at this late date I’m teaching myself WordPress in order to build myself a website. “Read Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography,” Gatto writes, “for an example of a man who had no time to waste in school.”

This leads naturally to Gatto’s solution: a free marketplace of school choices, from homeschooling to nontraditional schools, or any combination of those. He says US public schools have produced dependent, emotionally stunted, devious young adults who develop these traits trying to maneuver the pedagogical penal system. Gatto concludes that public schools have only one real purpose—to protect and perpetuate themselves: “We cannot afford to save money by reducing the scope of our operation or by diversifying the product we offer, even to help the children grow up right.”

Learning happens best, Gatto contends, in the family and in the community. But those former bedrocks have been supplanted by the public school system, which has now become a de facto social services agency.

As an illustration of this grassroots, freewheeling learning, Gatto describes in detail his own extracurricular education. He grew up in the forties and fifties in a small town, Monongahela, just south of Pittsburgh (it’s also the hometown of former NFL quarterback Joe Montana). He got into some minor trouble now and then and was held at the police station by Charlie the cop. One time he broke the window of a police car with a slingshot on a dare, and his sentence was to sweep up in his grandfather’s print office to pay for the glass, his first job, at fifty cents an hour. He roamed around with the other kids in town, not a helicopter parent in sight. He learned from everybody and everything—even from the omnipresent green and wondrous (at least to a boy) Monongahela River, where paddle-wheel steamboats churned along. And he learned from the trains that stopped in town: the engineer and brakeman used to spin stories, give advice, and let him and his buddies onboard the cars and, once a year, the caboose, which smelled of stale beer and adult life.

These days alternatives to public school are available “only to the resourceful, the courageous, the lucky, or the rich,” Gatto says.

Perhaps the internet is changing that, not only with more accessible resources but because of the work-from-home movement that only a couple of years ago, prepandemic, was mostly resisted by employers but is now a reality. According to the National Home Education Research Institute, nearly four million American kids were homeschooled during the 2020–21 school year (many of them are no doubt Christians, since the Bible, and now everything it stands for, has been verboten in US classrooms since 1963). That number might be higher if it weren’t for both parents usually working outside the home. Indeed, the public school has become a convenient but expensive—and insidious—babysitter.

If you’re still not convinced about Gatto’s unconventional assertions, he might exhort you to consider your own public school career. Mine bears him out, with the exception of a couple of bright spots.

But it wasn’t until seventh grade that the first really good teacher—he taught social studies and became my wrestling coach, not only in junior high but for my junior and senior years in high school too. I learned a lot from wrestling that I couldn’t have learned in a classroom, and most of it was because of him.

The second one was when I was required to take Writing Workshop my senior year. We started each class with a five-minute freewriting, and sometimes did more freewriting over the better part of an hour. Our teacher also moonlighted as a theater reviewer for the local daily (which I became a reporter at a few years later), ran the school newspaper, and gave me my first public praise as a writer: my essay was the only one he read aloud to the class (it was about wrestling, of course). He asked me if he could publish it in The Proud Tiger, but I refused. I felt exposed, but I was intrigued too.

Could those two pivotal and intertwined events in my life have happened if I’d been homeschooled, for instance? I think they could have. Homeschoolers can take part in extracurricular activities at the local public school. And I discovered long before Writing Workshop that I didn’t stutter when I talked on paper.

Then there were the bad teachers—really bad.

Most of the elementary schoolteachers in my school in the mid-sixties (around the same time as Milagros) were women. Only one of them I liked, but one of them was sadistic. My first-grade teacher, who reminded me of the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz, used to yell at me after she called on me to read and I couldn’t make any sound come out of my mouth because I stuttered. I had to precede the first word with “hey.” “Hay is for horses!” she mocked me in front of the class.

Then it was Christmas time, and we were rearranging our seats into groups with our desks pushed together. Mine wound up right next to this girl who was not well liked, and I said under my breath, “I hate girls.” All I meant was that I wanted nothing to do with them because, at least back then, they couldn’t play football or baseball or basketball. The Wicked Witch slapped my face! Then she made me move my desk into the back corner, away from the other desks, and I had to stay there until I apologized to the whole class. I finally broke down after about a week of semisolitary confinement.

Her mini-reign of terror raged on. At lunch she threatened me that if I didn’t eat the overcooked mushy carrots I hated and had therefore left uneaten on my plate, I couldn’t go out for recess, which I absolutely loved. I forced them down. I dually threw up in the cafeteria. When I told my mother about it, she just shrugged it off. She was busy, my father too, they had enough to take care of with my younger brother, who was born with Down syndrome and was never able to walk. From then on I brought my lunch to school until I’d escaped to junior high.

Then there was high school.

My freshman year I had this middle-aged guy with a big mustache and curly hair and glasses (it was the mid-seventies) who taught earth science. But he really did no teaching. He didn’t lecture at all. And the textbooks were all lined up on shelves under the wall. We were supposed to learn by doing labs and looking things up when we needed. Well you know how labs by freshmen in high school go—they often get willy-nilly results. If we had a question, we’d ask the teacher, and he’d answer: “Namowitz and Stone” (the authors of the textbook), page such and such. And he’d giggle wildly like some cartoon mad scientist.

Anyway we were all lost, even me, the straight A student. We discovered this when our so-called teacher gave us a sample Regents test. I was stunned that after a whole school year I knew next to nothing about earth science.

Thankfully, a short time after that, I was up at the mall and as I walked out of the guitar store I saw all these bright-red paperback books displayed in front of the bookstore— Barron’s Regents review guides for all the subjects. Each one had sample tests, but what’s more it contained a summary of the entire course, everything you needed to know in a fraction of the pages! I bought it, read it, and took the tests. And I scored, if I recall correctly, a 90 on the Regents! All for about a week or two’s worth of work! Almost everyone else did poorly, and quite a few failed; again, if I recall correctly, only four students scored in the 90s.

I had found my Rosetta stone, and used it for all the rest of my Regents courses. As Gatto might attest, however, it’s not a good idea for a student to show the typical public school teacher that you don’t need them.

I found this out firsthand my sophomore year when I took biology. I did as little as possible. Biology was one of my best and favorite subjects—I even had a sizable vegetable garden of my own around the same age. The teacher, however, was far from my favorite. He was the kind who liked to flirt with girls and crack jokes; he had a weaselly voice and way about him. I just put my head on my folded arms on the desk. I had a 98 or 99 average. I was in effect saying I didn’t need him.

Two years later I unknowingly rekindled the war. I made the grave tactical error as a senior of signing up for ecology, an elective no less, but a subject I was attracted to because of my interests. But in my naive way, forgetting my lessons on the mat, I didn’t do the political calculus; I’d given my opponent a prime chance to retaliate.

At the end of the first quarter, which was also the start of wrestling season, I received a “warning letter”—my first ever—that I had a D in ecology! Our grade was determined by a weighted formula of test scores, participation in class, and field trip attendance. I told the weasel that I couldn’t go on field trips because I had wrestling practice, I had been wrestling for four years and wasn’t about to blow my chance for a state championship on something that was after school. My time after school was my time, and I was going to spend it the way I wanted.

He told me that I was going to go on the field trip or fail the class, and that he was going to talk to my wrestling coach. He actually came into wrestling practice, but my coach—my mentor—told him the same thing I had told him.

I showed my coach the warning letter, and he told me to take it to the guidance counselor and tell him the whole story. I did, and to my surprise, the guidance counselor said: “Let’s go down and talk to Mr. —.”

We went down to the old biology room, and there I was sitting across the lab table from my nemesis. He made his opening statement: I never participated in class; I laid my head down on the desk; I took no notes, didn’t even bring a notebook to class; and I refused to attend field trips.

Then it was my turn for rebuttal. I said that I had an 85 test average, which I thought reflected the knowledge I have of the subject. I was using their own rules against them; test scores are the ultimate currency in public school, and when you had grades like I did, I knew they couldn’t really touch you. I said no other teacher graded class participation. And field trips were after school, therefore I shouldn’t be graded on something I’m technically not required to attend. I reported that I had told him about wrestling practice and my career, but that he didn’t care.

Finally, I said the warning letter should be retracted. And it was!

Anyhow, these are the kind of games many adults who call themselves teachers, and the only ones whom the state officially recognizes as teachers, play against children and adolescents. And enrich themselves doing it, in the form of generous pensions they can start collecting in New York state at age fifty-five.

So those are the highlights of my dozen years of hard time in the public schools.

I can see Gatto nodding his white-haired head. He never again saw the pure-hearted girl who had started it all for him all those years ago, for better or for worse. But one day in 1988 he read about her in a newspaper: Milagros, now in her early thirties, about the same age then as her defender was when they met, had won the state Distinguished Occupational Teacher Award; she taught secretarial studies in high school. And in 1985 she’d been named the Manhattan Teacher of the Year.

“No matter,” Gatto says, addressing her in Dumbing Us Down, “a teacher like you cannot be found.”

Still, how bittersweet it must’ve been for the old contrarian to find out what had become of his former star student.

__________________________________

Jeff Plude is a Contributing Editor to New English Review. He was a daily newspaper reporter and editor for the better part of a decade before he became a freelance writer. He has an MA in English literature from the University of Virginia. An evangelical Christian, he also writes fiction and is a freelance editor of novels and nonfiction books.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast