by David Solway (March 2024)

Two books on terrorism and the “terrorism industry,” John Mueller’s Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats and Why We Believe Them and Robert E. Goodin’s What’s Wrong with Terrorism, develop an ostensibly dispassionate account of the revisionist perspective on the “war against terror.” While some good sense may be found in them, these books abound with tenuous assumptions and partisan arguments associated with the Left, which attempts to minimize the threat of terrorist violence by “putting it into perspective.” Goodin’s thesis that a Republican administration is prone to using scare-mongering tactics, to “play[ing] the terrorism card,” in order to obtain political advantage, is par for the course.

The trouble is that Mueller and Goodin are playing their own terrorism card in order to obtain polemical advantage. The statistical claims they deploy to convince us that Islam is essentially a peaceful religion, that the jihadists form a transient minority, that the terrorist threat has been highly overrated, and that the problem is really our fearful over-reaction to what amounts to a relatively insignificant casualty count are a tissue of simple-minded inferences and deductions that rely mainly on the abstract power of comparative numbers. But Mueller and Goodin seem completely unaware of the way in which statistics can be misused as well as faultily collated. As the old saw goes, “Do not put your faith in what statistics say until you have carefully considered what they do not say.”

Let me indulge an explanatory aside. Take those reassuring statistical comparisons which tell us that air travel is far safer than driving. But is this belief really warranted? Do we ever stop to reflect how flimsy and truncated, even misleading, such quasi-mathematical structures really are? For example, a minor mechanical malfunction in an automobile will likely lead to nothing more than stopping by the side of the road, pulling over to a service station, or simply waiting for a convenient moment to address the problem; a similar malfunction in an airplane—a door poorly bolted, an aileron insecurely attached—may plausibly lead to a hecatomb. My sister’s parents-in-law caused roadside hilarity when the back half of their car remained behind when the traffic light turned green. There would be no hilarity if the back half of an airliner fell off in mid-flight.

Properly speaking, the term “minor malfunction” is instrumentally inappropriate in describing the mechanics of flying. When we board an airliner, we know instinctively that nothing must go wrong, a presentiment absent from the morning commute. A sensor gives a wrong reading in a car: we’ll attend to it eventually. A sensor gives a wrong reading in an airplane: hundreds may die. How can these situational elements, the brute empirics of what is known as the “informal realm,” be calculated and integrated into a statistical equation? And how can we quantify the sense of vulnerability that modifies our affective response in evaluating the likelihood of danger? There is no viable technique which allows for the compilation of such incommensurable variables or their systematic factoring into a nomothetic transfer frame.

Further, there is the problem of adjustable distributions, that is, there is no precise way of calculating how many times a person gets into a car every day or what the distance, duration and conditions of such journeys may be, extrapolated over a year from a sizeable population whose numbers would be astronomical where numbers even apply. These data are in their nature inaccessible, but common sense suggests that were such a God’s-eye view possible, our statistical computations might well generate a wholly different set of conclusions from those provided by mass casualty counts and rough correlations.

Airline travel is at least theoretically capable of being calibrated and the relevant data are at least theoretically manageable, but the same is not so with respect to road traffic. Were it feasible, however, to measure reliably the number of hours we spend on average in a car or truck or taxi or municipal bus or Greyhound or motor home over a large enough temporal gradient, as well as the nature, frequency and duration of these journeys, the various distances travelled, the physical condition of the driver, the actual road and weather conditions which impinge at all of these times, and the number of mechanical malfunctions that may be disregarded without risk, the results pertaining to the relative safety-quotients between vehicular and air travel might well be several orders of destabilizing magnitude different from the purring statistics that sedate us into a false sense of security when it comes to flying.

We might well discover in the light of a complete dataset that traffic fatalities are remarkably low and airline mortality is comparatively high. The current statistical distributions with respect to the comparative dangers of driving and flying depend on the available data which are crucially—and inherently—inadequate to producing accurate results and certainly incapable of supporting the wished-for consensus. Our findings are skewed by the twin constraints of data-inaccessibility and weak or imperfect distributionalism, which effectively obscure the very real possibility, in line with our intuitive convictions, that flying may be enormously more perilous than driving.

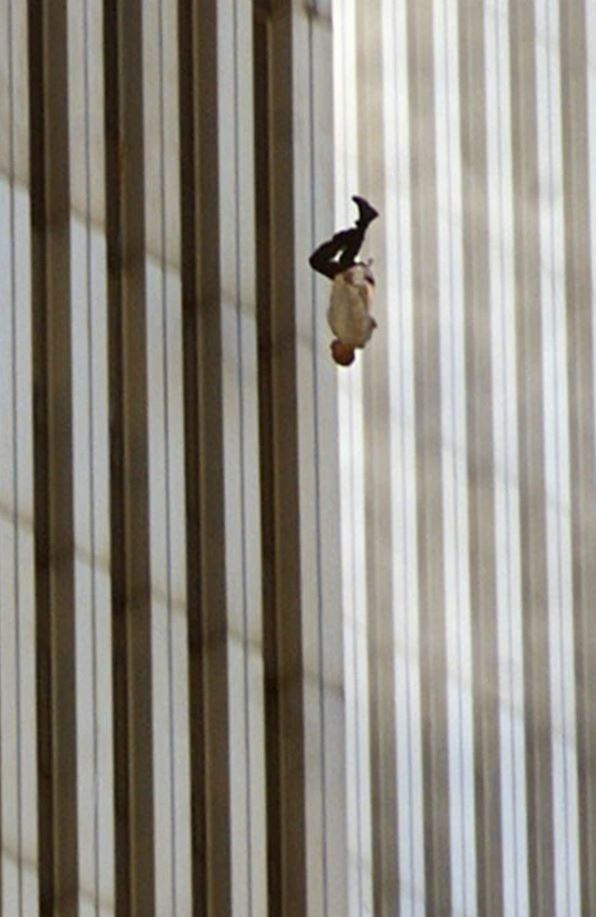

The same facile assumptions dominate the revisionist discussion of terrorist casualties vis à vis domestic fatalities. The issue does not revolve, as Mueller crassly suggests, around the 40,000 traffic deaths per annum in the U.S. as opposed to the (merely) 3000 victims of the 9/11 massacre. The question is profoundly more complicated than such lumpish arithmetic implies, entailing as well a failure of imagination. If Mueller were jumping from the upper floors of the Twin Towers, he might have reconsidered. The statistical apparatus that is usually brought to bear upon the events in question is not only starved of sufficient data and personal empathy but is meant to distort our perception of the situation in which we are embroiled. It cannot accommodate, as the above heuristic should establish, the scalene and empirical properties of certain sorts of phenomena—in this instance, what we might refer to as “crisis events” and the profound insecurity they inspire.

Additionally, there is a third element which qualifies the conceptual structure we are working with, namely, the conscious feature of harmful intent, of premeditated malice. Terrorist events are informed by sentience—they are not the outcomes of chance or randomness which are variously if not completely susceptible to mathematical/statistical constructs. With the one, we have the unsettling feeling that someone is gunning for us and is prepared to wait for the opportune moment, which cannot be statistically predicted; with the other, well, that’s life, and we do not feel personally victimized by what is arbitrary or contingent. The Muellers of this world, I’m afraid, are not so much doing the math as doing the myth. Consider the following aspects and salients of terrorist operations, both statistical and practical.

- Deaths due to terrorist attacks are additional deaths; they should not be tactically compared with other kinds of fatalities to establish relative scale but added to them, giving us even more to worry about, not less.

- The psychological effect, which owing to the “explosiveness” of terror episodes, their spectacular nature and the amount of immediate damage they can do, is far more conspicuous and, indeed, terrifying than what a randomly distributed traffic score can incite. The psychological repercussions are not so perfunctorily logicized away.

- As a corollary of the above, in assessing a major terrorist assault such as 9/11, the gruesome details along with the anterior purpose cannot be clinically dissembled. 3000 deaths in one hour and in a single, circumscribed spot of approximately one square mile is a much different kind of event than 40,000 deaths spread out over twelve months and across fifty states, or approximately 3,537,444 square miles—which scarcely registers on the psyche and certainly not in the same way as a terrorist atrocity. Macroscopic facts of a fortuitous nature and relating to large variables are diluted over time and itemized cumulatively rather than felt on the pulses as a kind of fungible singularity. Nor, as noted, are they the product of deliberation. The human significance of the aleatory is always thin. But a carefully planned attack with the intent of inflicting maximum harm and yielding instantaneous consequences of the most frightful nature is another matter entirely. Its effect is like that of an asteroid slamming into the earth, which doesn’t happen all that often. Once is enough. Yet it happens often enough to give us pause. Recalling Paul Brodeur’s dictum in Outrageous Misconductthat “Statistics are human beings with the tears wiped off,” the inapplicability of statistical instruments to cognitive incompatibles and the essential grotesquery of the procedure should be evident.

- A second corollary entails the economic impact, which follows from the inevitable psychological effect. We saw what happened to the airline industry, the tourist trade, the Nasdaq, the export and import enterprise, and the oil prices after 9/11. If the London hijackers had succeeded in their 2006 plot to bring down ten airliners over the Atlantic within minutes of one another, important sectors of the market would have imploded and the livelihoods of many people around the world would have been ruinously affected, which is manifestly not the case when we consider the accidents that happen on the nation’s highways, kitchens, bathtubs or hiking trails.

One scarcely has the patience to engage these soi-disant scholars manipulating their number games intended to tranquillize our justifiable fears—a ton of sarin gas would cause only “between three thousand and eight thousand deaths,” we are told. Can these people be serious? This isn’t bingo. This is moral insanity, the verbal Hackey Sack of those who have nothing better to do with their time. Deaths numbered in the thousands “can be readily absorbed,” declares the ever-cavalier Mueller. The logic is abominable. I don’t know whether this is infantile thinking or magical thinking, but I do know that it is both shallow and barbarous thinking—if it is thinking at all.

Indeed, what we might call the Argument Spurious is a veritable stock in trade of such writers. For Mueller, a radiological attack is not the calamity we consider it to be for in its aftermath “medical and civil defense measures can be deployed” and antidotes administered—but the state of preparedness of our responder networks plainly indicates that unmitigated chaos would ensue, aside from the fact that the targeted area would be radioactive for years to come. For Goodin, we should refrain from magnifying terrorist activities out of proportion, which explains why he praises the British government for its low-key response to the transit bombings. True, Goodin’s argument that the war on terror may profit politicians by enabling them to strengthen their own authority is largely valid. We must give him that. The irony is that the Department of Homeland Security, which as we see today has turned against many of its own citizens, has become an instrument not of the Right but of the Left, with which Goodin himself is emotionally affiliated. But such a development, while regrettable, does not minimize the insidious prevalence of the jihadist threat.

***

The old political maxim, “Where you stand depends on where you sit,” is apt. Our authors have padded their sitzfleisch in prestigious academic appointments, Mueller on the Woody Hayes Chair of National Security at Ohio State University, Goodin at the Australian National University. Not much in the way of rigorous, peripatetic inquiry of a classical strain here. A university Chair is a sedentary thing; and, as often as not in today’s PC climate, a tenured position is a neural carapace. That is why a plagiarizing incompetent with the thinnest of resumés like Claudine Gay could have been appointed to the position of president at Harvard University.

We should keep in mind that far too many of our intellectual luminaries live in a beta version of reality, a sort of pastoral interlude protracted, which those whose livings are dependent on the trades and the markets should be skeptical of. Serious people do not sport in the Forest of Arden. The Duchy of the Actual is a non-contiguous zone, existentially remote from the land of visionary seminarians and yet ideologically porous to their species of advocacy. This it is that renders the activities of these “specialists” in international affairs suspect. For when these seignorial capacities pronounce on the incendiary issues of the day, the result is more likely to be one of noxious bathos than, as we have been trained to expect, counsels of sound judgment. The burden of lean and wasteful learning sits lightly upon them as they fail to examine the gap between cloistered immunities and realworld detriments.

To sum up: The grass is not only greener in Academia but, compared with the precarious terrain outside the portals of privileged lucubration, there is usually more of it—and as the Bard says, good pasture makes fat sheep. The obsessive yonderings of most of our university-bred virtuosos cannot deputize for harsh truths. Unfortunately, nothing will convince them of the chronic nonsense purveyed in their writing unless they or their loved ones should be incinerated in one of those terrorist attacks they habitually downplay or if their kids attending a music festival in Israel had been among the hundreds slaughtered by Hamas terrorists. Statistics wouldn’t matter much then and neither would consoling fictions. As Albert Camus ruefully stated in his Algerian Chronicles, “we could have used moralists less joyfully resigned to their country’s misfortune” and, we might add, less willing to use statistical lattices to make light of the real menace we face in a terrifying world.

Table of Contents

David Solway’s latest book is Crossing the Jordan: On Judaism, Islam, and the West (NER Press). His previous book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London. A CD of his original songs, Partial to Cain, appeared in 2019.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

3 Responses

Indeed, I recently suffered the indignities of travelling to the West Coast by air, waiting in tedious queues only to be crotch handled by some obese TSA crossing guard looking for nail clippers. My pace maker triggered the alarm. Flying is now a cattle drive. Now, every time I enter an airport, I am reminded how much Islamic fascism has changed our daily lives for the worse.

A superb piece. The Falling Man image haunts— we simply cannot understand how someone applying make-up or trying to cover a bald patch ten minutes earlier in front of a washroom mirror could jump. The details of airplane crash, explosion and heat explain don’t provide understanding. The statisticians’ explanation reminds of an awful line —a guy falling from the 100th story declares at the 50th floor that on average things aren’t so bad.

Wow thanks, meticulous reasoning. True that, how there is not a murderous ideology helped along by sniveling government victimhood promulgators driving the 40000 traffic fatalities. And an elite forcing us to deal with the FAA every air trip, instead of honestly discussing a hostile incompatible culture invited into our country decades ago.