Review of I am André: German J French Resistance Fighter, British Spy

by Juliana Geran Pilon (February 2025)

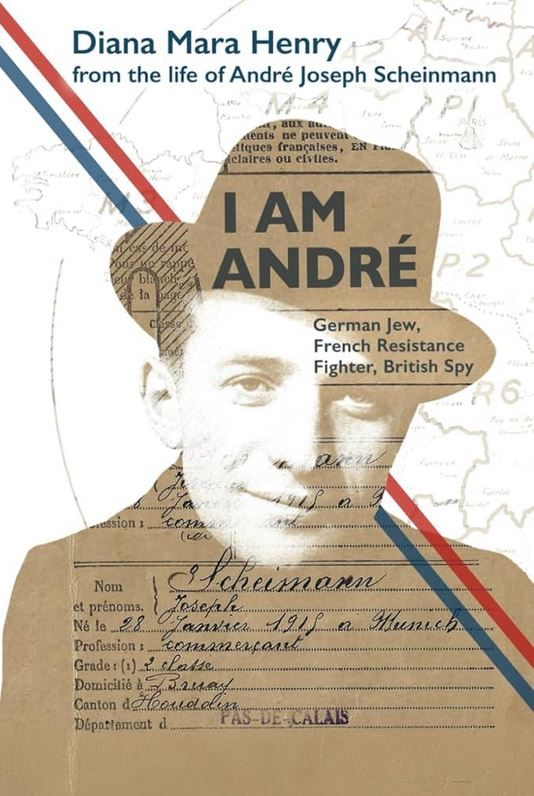

A sepia-colored photograph of a handsome young man dominates the cover of I Am André. A warm yet slightly mischievous smile mirrors his kind eyes which seem filled with an ocean of unshed tears. The ghostly image intimates the improbably kaleidoscopic persona of its subject as captured in the subtitle: German Jew, French Resistance Fighter, British Spy. A French document, masterfully superimposed, reveals his birth date: January 28, 1915; and place: Munich. First name: Joseph. Last name: Scheimann. Actually, it was Scheinmann, but it didn’t matter—not many people knew his name.

Or, rather, names. After Joseph Scheinmann officially joined the resistance after the German occupation of France, British intelligence helped him obtain a certificate with a new name: André Peulevey. Citizenship: French. No one was to know that he was a Jew. He would not reclaim his real name until 1951.

Or, rather, names. After Joseph Scheinmann officially joined the resistance after the German occupation of France, British intelligence helped him obtain a certificate with a new name: André Peulevey. Citizenship: French. No one was to know that he was a Jew. He would not reclaim his real name until 1951.

He liked “André”; it was his preferred nom de guerre (he had others). It had served him well throughout his unique career, which had begun in his teens as a Jewish anti-Nazi rebel, in Munich. He was following in his father Max’s footsteps. A proud World War I veteran officer, starting in 1923, Max began speaking out in public meetings, travelling across Germany to rally veterans against Hitler. Luckily, he had the foresight to take out French visas for his family in 1924, which came in handy in 1933, when he realized there was no other choice but to leave. The family fled. Although his mother managed to save a few items, Max had been prepared to leave everything behind – money, stores, furniture. They would start a new life.

France had seemed safe, though ominous clouds were gathering fast. Then in 1939, Max accompanied his daughter Mady to the U.S., where Max’s parents and brothers had been living, to attend her wedding. He would then return to Paris to rejoin his wife Regina and son Joseph, who by then had joined the French army. The date was September 1. He must have had a premonition that he was sailing back into hell, and would never see America again.

Max didn’t know that Joseph had already begun his career as a spy and saboteur, but he could not have been surprised. After leaving the army, Joseph started working undercover as translator and liaison with the German high command at the Brittany headquarters of the French National Railroads. It proved a fortuitous assignment. From the summer of 1940 till February 1942, he learned what types of German troops were moving when and where, with what kind of armaments, as well as other information of vital importance to the British military, enabling them to inflict upon the Nazis massive physical and psychological damage. His position also provided an opportunity to recruit a wide network of agents willing to sabotage and spy for their country.

His work provided excellent cover as well for clandestinely crossing the Channel for training as an MI6 agent. Only after being betrayed by a careless comrade did that end. Tragically, he was arrested upon returning to France, in February 1942. To his relief, thanks to prudent spycraft and fast thinking, he had made all the documents in his possession disappear before falling into his captors’ hands. The Nazis learned nothing from him. Subjected to torture and interrogation, he admitted nothing. It saved his life.

But not his freedom; he was sent to concentration camp Natzweiler-Struth in Alsace, France, which the Nazis themselves considered Category 3, “the harshest.” Once again, his endless ingenuity, reinforced by providence and luck, saved him. He soon managed to secure a job as translator to the French inmates, which afforded him a host of opportunities to help fellow prisoners—and without in any way compromising their dignity. He even managed to mock the Nazi guards! Given his intimate understanding of German mentality, and without a trace of obsequiousness, he also gained a position of leadership that enabled him to recommend the most vulnerable inmates for placement in easier jobs. After befriending a sympathetic doctor, he also managed to send a few for brief hospital stays, to regain their strength. So when resistance comrades provided him an opportunity to escape and fight outside, he declined. He told them he could not leave his comrades “exposed to the punitive measures of the SS.” They understood.

Before being liberated, he would be transferred to two other camps, Allach and Dachau. The odds of survival in those notorious death traps were infinitely small. He credits his “upbringing, traditional Judaism and bourgeois habits” for keeping a positive attitude throughout, and never losing his self-esteem. He found that “humiliation was suffered by all nationalities, but war harder to bear by people of higher social standing,” who missed their privileges. “If one had no genuine identity in oneself and identified only with professional and social rank, to a caste or special group, he was lost—not only because of physical degeneration but because of mental destruction.” (155) Besides being morally commendable, preserving one’s dignity is lifesaving.

His parents meanwhile had been trapped inside Germany. Somehow, André kept hoping that that he would be able to save them. But unbeknownst to him, their application for visas to join their family in the U.S. had already denied by the State Department on June 23, 1941. Exactly a year and a month later, they were gassed at Auschwitz.

He never forgave himself for their death. In his diary, he never mentions the infamous visa denial. Yet he must have known the Roosevelt Administration’s record of restricting Jewish emigration during the war to a mere trickle. He did not deflect responsibility from himself. And he loved America. That is where André spent the rest of his life, after eventually being able to recover his real identity. In 1952, he was finally able to join his sister Mady and the rest of his family in the U.S., bringing with him his wife, Claire Dyment. A fellow British spy later awarded the British War Medal for her war-time services, Claire had emigrated to England from Poland; she too had lost her parents, alongside the rest of her relatives, in the Holocaust. The two had a deeply loving marriage until her death in 1985.

In America, André continued to record as many of his wartime memories as possible. It would take decades to gather the necessary documentation. Then one day, in 1994, his son Michel introduced him to his old friend from Harvard, Diana Mara Henry, who Michel knew had been researching the Natzweiler camp. Would she like to meet a survivor? His father, he told her, was giving a speech nearby, perhaps she could hear him. She did. It changed her life.

André would later entrust her with his manuscript. It proved to be a goldmine. Undertaking her research pro bono, she moved close to André’s residence in Massachusetts, so she could consult with him regularly. Andre did not have to importune her, as he did in their last meeting, before his death in 2001, “to tell his story ‘for my comrades.’” (171) She ended up doing far more. The photojournalist-turned-Holocaust scholar would spend three decades collecting countless personal papers and incorporating newly declassified documents from both French and British national security archives. Indeed, much remains still to be studied. Having undertaken her research pro bono, she moved close to Andre’s residence in Massachusetts so she could consult with him regularly.

Her decision to add both an introduction and conclusion for a fuller context adds enormously to the story’s ultimate impact. While André had offered a remarkably thorough picture of local resistance forces brilliantly coordinating with De Gaule’s forces in exile and their indispensable allies, mostly British and later American, Henry was able to collect additional information. His friends and contacts had cut across all segments of the resistance, broadly understood. She thus learned how “[r]esistance, espionage and counter-espionage” were intertwined. They had been “bedfellows in the war for liberation from the Nazis, and not just in France, and not just in Britain.” (176) Resistance turned out to be widespread throughout Nazi-infested Europe.

The self-sacrificing heroism of countless ordinary people, however, complemented the no less unfathomable, outright sadistic cruelty of others, who seemed just as ordinary. Human nature is neither black nor white but susceptible to change in either direction; especially in extreme circumstances, some are able to overcome negative impulses, but others succumb. The concentration camp testimony that comes closest to taking a similar approach to the study of psychological responses to terror was Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s iconic Gulag Archipelago. Having survived hell, they had both wished to describe all of its nine circles, memorialize the victims, and try to learn from it all for the benefit of future generations.

André was doubtless fortunate to have met Henry, who took pains to incorporate information not available until after his death. She discovered, for example, that his diary had failed to provide full details of his own struggles. It was only from a doctor’s report from after the war, and from other survivors’ writings about André, for example, that we read about his chronic life-long illnesses, most having been inflicted by camp guards. On one occasion, they had “flattened him to the wall,” causing excruciating pain. Another time, he was gravely mauled by one of their attack dogs. Equally unreported was a fall he incurred during parachute training—this at a time when, according to reports by another participant, “at least half of the parachutes didn’t open.” It caused him permanent back pain. “Till the end of his life he suffered from the injury,” reports Henry, “and typically he mentions nothing about that in his writings nor does he give details of the training.” (195)

Henry observes that other survivor accounts of life in these camps included far more gory details than did André’s. His main purpose was to convey “how he and his partners in courage struggled to see, after 12 years, the defeat of the ‘1,000-year Reich.’” But he had an enormous capacity for compassion and appreciated it in others. She remembers how in one of their conversations, André paused “for several silent sobs about the German career officer who spent twelve years in concentration camps rather than join the SS.” (12) He also singled out Abbot Bidaux, who also “never surrendered,” adding that “if there is such a thing as a saint, he was one … Men like him can bring people back to a belief in God, to be good and to believe in high ideals.” His memory, alongside that of Father Jean Legeay, who would be decapitated by the Nazis, “will always be alive in me. They were soldiers without the uniform.”

No ethnicity or religion has a monopoly on character; each of us is an individual. This, he knew, was America’s founding creed as well, which is why he was so fond of America. As he writes in the conclusion to his diary: “I have had no political ambitions and no longer take on noble causes, but I am happy to live in a country where men are free and can live according to their own convictions.” Observing that the world is still in turmoil, he has one message for the young generation: they must carry on, never taking their privilege for granted. “Freedom of mind and physical freedom are a must, yet only when we lose them do we value them. No matter what the odds, these are worth fighting for. Even if the fight seems impossible to win, one must never give up. This is why so many women and men went to the ends of the earth, never to come back. And we few survivors must make sure their sacrifice was not in vain.”

He traces the spiritual root of his convictions to discussions with his Jewish friends during the 1920s. It was then, he writes, that “I came to a deeper awakening to Zionism and to my place in Jewish history. Around the romantic campfires, I joined the nostalgic singing and I felt in my element, in my own milieu, a sense of belonging to my own people. Sure, there were divisions between the Eastern Jews and the assimilated German Jews, but just the same, we were entre nous (among intimates). Discussions touched on many subjects of Jewish life and history, including the heroes the Jewish people”(36), whose descendants we all are.

Or rather, can be—if we have the courage. Two decades later, Joseph Scheinmann became one of them. But so should any human being lucky to live in a civilized world. Jews had been meant—at least in principle, though unfortunately not always in fact—to serve as a moral beacon, defending not merely their own tribe but the biblical imperative of freedom. He ends the diary with this entreaty: “Never give up, even against all odds. Never give in to naked power and oppression. Live and help as much as you want others to.” Joseph/André did his part. It’s our turn.

Table of Contents

Juliana Geran Pilon is Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her eight books include The Utopian Conceit and the War on Freedom and The Art of Peace: Engaging a Complex World; her latest book is An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left. The author of over two hundred fifty articles and reviews on international affairs, human rights, literature, and philosophy, she has made frequent appearances on radio and television, and is a lecturer for the Common Sense Society. Pilon has taught at the National Defense University, George Washington University, American University, and the Institute of World Politics. She served also in several nongovernmental organizations, notably the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), where as Vice President for Programs she designed, conducted, and managed programs related to democratization.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

powerful story