by Kenneth Francis (January 2018)

The Death of Chatterton, Henry Wallis, 1856

sn’t it odd that the enormous volume of highly artistic works—from movies, drama, literature, poetry to music—are invariably bleak but give us immense joy? (This is especially evident in the yesteryear world of popular music, but I’ll come to that later.) One wonders are we better off living in a fallen world after all, as a perfect one without strife would lack in artistic excellence. But does a world with immense suffering justify moments of optimism through the transient pleasures of the arts, despite their dark themes? After all, one can’t have Shakespeare’s work without its tragedy, or W.B. Yeats without a terrible beauty being born.

sn’t it odd that the enormous volume of highly artistic works—from movies, drama, literature, poetry to music—are invariably bleak but give us immense joy? (This is especially evident in the yesteryear world of popular music, but I’ll come to that later.) One wonders are we better off living in a fallen world after all, as a perfect one without strife would lack in artistic excellence. But does a world with immense suffering justify moments of optimism through the transient pleasures of the arts, despite their dark themes? After all, one can’t have Shakespeare’s work without its tragedy, or W.B. Yeats without a terrible beauty being born.

The German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) believed we live in the best of all possible worlds, despite the pain and injustice that exist. In fact, with the exception of George Berkeley and Leibniz, almost every philosopher from Plato to Wittgenstein leaned more towards pessimism in their outlook of life. Even in the world of theatre, from the ancient Greeks to contemporary drama, tragedy plays a profound role in defining Western civilization, while evoking sadness and joy resulting in catharsis in audiences. Think about it: besides theatre and cinema, all the TV soap opera dramas infused with misery paradoxically give millions of fans worldwide immense pleasure; similarly, dark, melancholic paintings in the genre of Romanticism (‘The Death of Chat terton’) are far more stimulating than a Kitsch ‘Dogs Playing Poker’ by Cassius Coolidge.

terton’) are far more stimulating than a Kitsch ‘Dogs Playing Poker’ by Cassius Coolidge.

But back to the world of popular music, where so much misery has given us so much joy. Such a dichotomy was captured in the 1932 song, Mad About the Boy, written by the playwright Sir Noel Coward. The song, like most great love songs, is about unrequited love. It is usually sung by female singers, lamenting the odd diversity of misery and joy while being in the metaphorical bondage of such a “foolish” infatuation.

But just because a song is sad or depressing, doesn’t mean it’s without artistic merit, both lyrically and melodically. Any local priest will tell you the many requests they receive for bitter-sweet songs from brides and grooms, who unwittingly want them played for their nuptial ceremony. Songs like Help Me Make it Through The Night, Knocking on Heaven’s Door and You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling were popular favorites for those walking up the aisle in recent years.

I once heard of a couple who requested the Tammy Wynette song D-I-V-O-R-C-E to be played for their ‘first dance’ after the wedding ceremony. However, below I’ve chosen a handful of depressing songs that gave, and still give, great pleasure to music lovers worldwide, despite their depressing lyrics. To narrow the dreariest hits down to the top 5, read on and see if you agree.

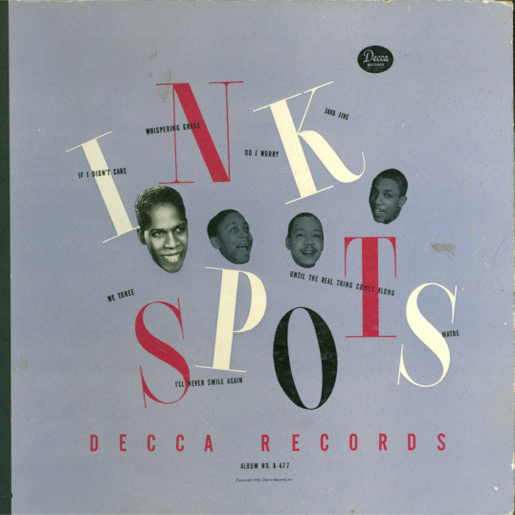

Coming in at Number 5 is The Ink Spots, with We Three (My Echo, My Shadow and Me). The Ink Spots, who were a vocal group during the 1930s-’40s, made this 1940 song a radio favorite. The song opens with the lyrics of a spiritually tortured, lonesome trio, isolated in the mind of a lost soul searching for love and company:

We three, we’re all alone

Living in a memory

My echo, my shadow, and me

We three, we’re not a crowd

We’re not even company

My echo, my shadow, and me

The song goes on to lament the silvery moonlight that shines up above, and how only ‘my echo, my shadow and me’ can experience it, ‘but where is the one that I love?’ The ‘three’ pledge to wait alone, even till eternity to find the one.

The theme of loneliness is no stranger to existentialist literature. In such a Godless landscape, we are thrown into this world and, ultimately, will die alone.

To echo the song’s lyrics, Jean-Paul Sartre said: “If you’re lonely when you’re alone, you’re in bad company.”

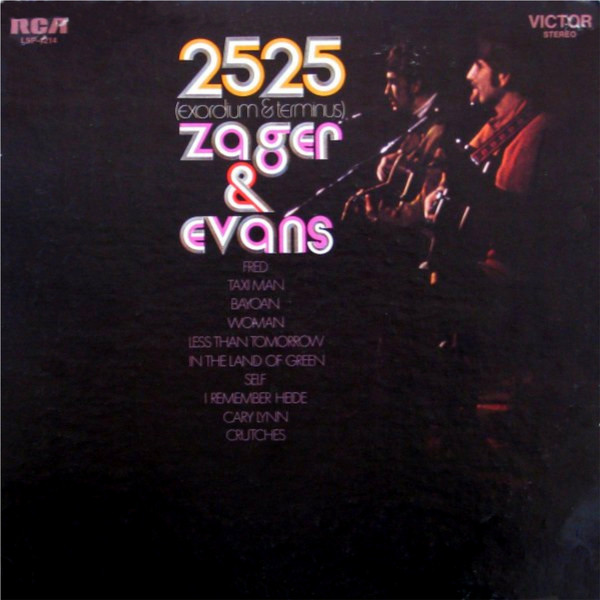

At Number 4, is the 1969 No.1 hit by Zager and Evans, In the Year 2525. This Brave New World one-hit wonder is not for the technophobe fainthearted. It’s the kind of song that could cause a luddite to overdose on Xanax. It opens with the words:

At Number 4, is the 1969 No.1 hit by Zager and Evans, In the Year 2525. This Brave New World one-hit wonder is not for the technophobe fainthearted. It’s the kind of song that could cause a luddite to overdose on Xanax. It opens with the words:

In the year 2525,

If man is still alive,

If woman can survive,

They may find . . .

Subsequent verses multiply the following years and chronicle them as a time when automated machines work our limbs because of an overdependence on technology; pills taken each day to make us think a certain way; marriage becoming obsolete, as babies are conceived “at the bottom of a long glass tube”. By the year 9595, Man’s reign is through, as humanity has wiped out everything, thus the last verse concludes:

Now it’s been 10,000 years

Man has cried a billion tears

For what, he never knew

Now man’s reign is through

But through eternal night

The twinkling of starlight

So very far away

Maybe it’s only yesterday . . .

Some other hits of 1969, such as the Fifth Dimension’s Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In or The Archies’ Sugar, Sugar were far less pessimistic, but they didn’t have the impact of ‘2525’. Works on dystopias are always threatening, as well as robotic technological advancements, which were (and still are) a source of worry to many intellectuals and philosophers.

In the last decades of his life, the existentialist German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) spoke about such threats, as opposed to its benefits. Philosophy professor Mark Wrathall wrote: “His preoccupation with ‘the technological mode of revealing’ was driven by the belief that if we come to experience everything as a mere resource, our ability to lead worthwhile lives will be put at risk. His task as a thinker was to awaken us to the danger of this age, and to point out possible ways for us to avoid the snares of the technological age.”

The less one hears of this dystopian classic, the sounder one sleeps.

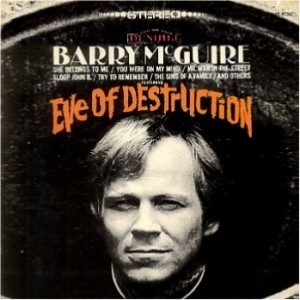

At Number 3, is the song Eve of Destruction, written by the late P.F. Sloan and sung by Barry McGuire. It was a No.1 hit on Billboard in 1965. Themes in this seminal protest song included the threat of nuclear war, racial tensions, JFK assassination and bloody middle-eastern conflict.

What’s most remarkable about this song is that the lyrics were written by a teenage boy. The protagonist of the song is that of a socially conscious person who’s been ‘Red-pilled’, trying desperately to explain the state of world affairs, which are on a razor’s edge. But the Pollyanna respondent keeps replying, “Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction”. Here’s a taste of some of the bleak lyrics:

What’s most remarkable about this song is that the lyrics were written by a teenage boy. The protagonist of the song is that of a socially conscious person who’s been ‘Red-pilled’, trying desperately to explain the state of world affairs, which are on a razor’s edge. But the Pollyanna respondent keeps replying, “Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction”. Here’s a taste of some of the bleak lyrics:

If the button is pushed

There’s no running away

There’ll be no one to save

With the world in a grave

Take a look around you, boy,

It’s bound to scare you, boy

And you tell me over and over and over again my friend

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction

The song also highlights the hatred in Communism, as well as Selma Alabama, and that marches alone won’t solve human rights issues. And it mentions the hypocrisy of some religious who hate their next door neighbour but “don’t forget to say grace”.

In Sloan’s obituary in the New York Times in 2015, Bruce Weber wrote: “The song was controversial; politicians and other musicians debated whether its message, that violence and hypocrisy were a grave threat to civilization, was an accurate depiction of the state of the world, a healthy message to transmit in pop music, or a reasonable representation of the outlook of America’s youth. It also changed Mr. Sloan’s life.”

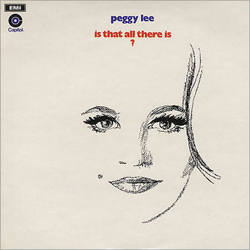

The eve of spiritual destruction is the theme of my No.2 choice, Is That All There Is.

In his book A Secular Age, the philosopher Charles Taylor wrote that some people long for ultimate meaning, and that longing may end with God. God is always breaking in, stepping through the immanent frame of secularism, according to Taylor. But when ‘secular’ God makes his appearance, Taylor finds, he sounds just like Peggy Lee, singing Is That All There Is? The song, arguably the most depressing song ever written, was inspired by the 1896 story ‘Disillusionment’ (Enttäuschung) by Thomas Mann. It sums up precisely the real meaning of secularism.

frame of secularism, according to Taylor. But when ‘secular’ God makes his appearance, Taylor finds, he sounds just like Peggy Lee, singing Is That All There Is? The song, arguably the most depressing song ever written, was inspired by the 1896 story ‘Disillusionment’ (Enttäuschung) by Thomas Mann. It sums up precisely the real meaning of secularism.

It tells the story of a young girl and the disappointments she experiences throughout her life. Everything seems empty and tinged with the melancholy of all things done. Finally, left with a broken heart when her lover leaves her, her last words confront a way out by suicide. But she finally says she’s in no hurry for that ultimate disappointment, uttering in her last breath: “Is that all there is?” Which brings us on to final, joint fusion of miserable, yet powerful songs: 21st Century Schizoid Man/Epitaph

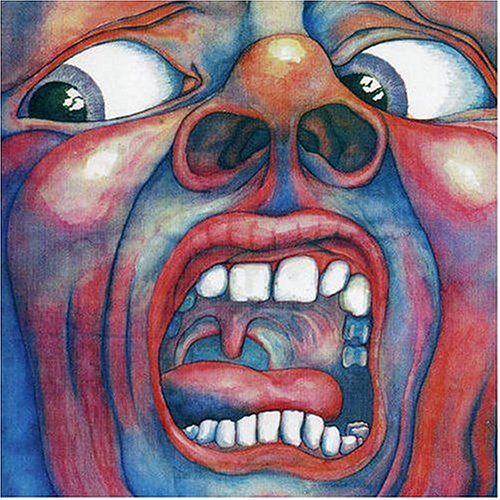

This song(s) fusion, from the album The Court of the Crimson King, by the progressive rock band King Crimson, was released during the height of the Vietnam War in 1969. It was also the era of Woodstock, when Country Joe and the Fish sang the satirical anti-war number, I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die:

And It’s one, two three,

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn,

Next stop is Vietnam,

And it’s five, six, seven,

Open up the pearly gates,

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why,

Whoopee! We’re all gonna die

Less satiric al but equally serious, the lyrics 21st Century Schizoid Man/Epitaph depict a series of tragic images and apocalyptic prophecy. The words have on occasions been quoted in his talks by the philosopher Ravi Zacharies, to highlight the ramifications of atheism and relativism. The lyrics begin with neuro-surgeons screaming for more at paranoia’s poison door:

al but equally serious, the lyrics 21st Century Schizoid Man/Epitaph depict a series of tragic images and apocalyptic prophecy. The words have on occasions been quoted in his talks by the philosopher Ravi Zacharies, to highlight the ramifications of atheism and relativism. The lyrics begin with neuro-surgeons screaming for more at paranoia’s poison door:

Blood rack barbed wire

Politicians’ funeral pyre

Innocents raped with napalm fire

Twenty first century schizoid man.

Death seed blind man’s greed

Poets’ starving children bleed

Nothing he’s got he really needs

Twenty first century schizoid man.

In Epitaph, the third track in the album, the lyrics point to the wall on which the prophets wrote, which is cracking at the seams, upon the instruments of death, the sunlight brightly gleams when every man is torn apart with nightmares and with dreams, will no one lay the laurel wreath when silence drowns the screams:

Confusion will be my epitaph

As I crawl a cracked and broken path

If we make it we can all sit back and laugh

But I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying . . .

. . . Knowledge is a deadly friend

When no one sets the rules

The fate of all mankind I see

Is in the hands of fools

Yes I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying

Finally, contrast the lyrics of the above songs with the optimism of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’, the opening song from the hit musical Oklahoma!

Oh, what a beautiful mornin’!

Oh, what a beautiful day!

I’ve got a beautiful feelin’

Ev’rythin’s goin’ my way.

If only life were so easy.

__________________________________

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 20 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing).

More by Kenneth Francis here.

Please support New English Review here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link