by Jeff Plude (March 2019)

Fruit Bowl, Book, and Newspaper, Juan Gris, 1916

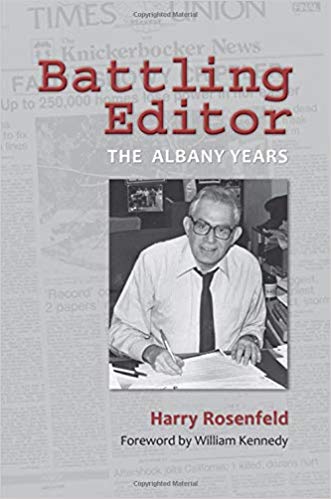

Solomon warns, “Be not righteous over much,” which I think would be a potent antidote for the recently published memoir Battling Editor: The Albany Years. The pugnacious title refers to the author, Harry Rosenfeld, who you may remember was metro editor of The Washington Post during Watergate, the direct supervisor of reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

To promote his new book, Mr. Rosenfeld gave a talk at the Albany Institute of History and Art in Albany, New York. Many of the fifty or so people there that cold gray December day were closer to his age, eighty-nine, than to mine. No doubt they were regular readers of the Times Union (TU) during the eighteen years he’d edited it, the third and final act of a newspaper career that spanned more than a half century, “the final days and years of a particular golden age of newspapers,” as he puts it. But I did more than read the TU—I used to be a reporter and an editor for the daily newspaper that Mr. Rosenfeld says he was battling against in the latter half of his Albany years.

To promote his new book, Mr. Rosenfeld gave a talk at the Albany Institute of History and Art in Albany, New York. Many of the fifty or so people there that cold gray December day were closer to his age, eighty-nine, than to mine. No doubt they were regular readers of the Times Union (TU) during the eighteen years he’d edited it, the third and final act of a newspaper career that spanned more than a half century, “the final days and years of a particular golden age of newspapers,” as he puts it. But I did more than read the TU—I used to be a reporter and an editor for the daily newspaper that Mr. Rosenfeld says he was battling against in the latter half of his Albany years.

As its title suggests, Battling Editor revels in the portrait of the crusading newspaper editor selflessly leading the charge for truth and justice on behalf of the public weal at all costs. According to its author, not only self-serving politicians but the paper’s own brass order him again and again to stand down, more or less. He’s had to confront a mega-cyber weapon too. But he marches on. Dodging both enemy and friendly fire alike, Mr. Rosenfeld paints himself as the Patton to his ink-thirsty reporters. Old Ink and Guts.

Read more in New English Review:

• Real People

• Twentieth Century Architecture as a Cult

• Some Thoughts on the Empty Heart of Modernism

It’s a tiresome and overdrawn picture at best, as if power (let alone money) had nothing to do with it at all. At worst, it’s the latest mainstream media embodiment of what Timothy Crouse calls, in his groundbreaking 1973 book The Boys on the Bus, a “shy egomaniac.” Battling Editor can also profitably be read as an unintended individual case study of the press-pack mentality that Mr. Crouse chronicled during the presidential campaign that lead to Watergate.

For me, Mr. Rosenfeld comes off more as a baffling editor than a battling one (bristling is more like it). I’m baffled by his host of self-contradictions. One moment he’s speaking truth to power, the next he’s chummy with it. Politicians are corrupted by power and lies, but the members of the press are sacrosanct and free of, for the most part, self-serving motives. Journalists serve the public out of the goodness of their hearts and souls, but the beneficiaries of this largess seemingly have no right to doubt Mr. Rosenfeld or his cohorts or hold their own feet to the factual fire.

Battling Editor picks up where Mr. Rosenfeld’s previous memoir, From Kristallnacht to Watergate, which was published in 2013, leaves off, with a little overlap. Unfortunately there’s a lot less of interest to tell in his new book. And what’s worth telling sounds more like it was written by a Hearst flack than one of its star editors, replete with glowing testimonials but light on soul searching.

He wasn’t quite fifty when he left the Post in 1978 as one of several assistant managing editors to become Editor of both the morning Times Union and the afternoon Knickerbocker News. He was stepping up but down at the same time, going from the nation’s capital to an obscure state capital in “upstate New York” (that vague wasteland of news stories). He says he came to Albany because he wanted to run a daily metropolitan newspaper from top to bottom instead of slave away in the middle of one, which he’d been doing since 1948 (minus a half dozen years for college and the Army) when he became a shipping clerk at the New York Herald Tribune in Manhattan.

In other words, he wanted to be a version of his imperial blueblood boss at the Post, executive editor Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee—as Mr. Rosenfeld invokes him in his preface. Quite.

Albany, whose population of 100,000 or so was about the same then as it is now, barely qualified as a suitable post for the semi-famed editor, though its metro area had about a million people. Herman Melville and Henry James may have been natives, as Mr. Rosenfeld points out, but what he doesn’t say is that they fled sooner than later and flourished elsewhere. The city was still controlled by a long-running political machine, which was Democratic, so there was at least one worthy opponent for the battling editor to pit himself against, though it started running low on gas after Mayor Erastus Corning 2nd died in 1983. And there was Mario Cuomo, who was governor for twelve years during Mr. Rosenfeld’s reign at the TU and at one time a Democratic front-runner for president.

The two became frenemies of sorts, occasionally exchanging letters. Mr. Cuomo once even hosted Mr. Rosenfeld’s starstruck elderly mother-in-law in the governor’s office. Mr. Rosenfeld had directed his Capitol reporter to ask for an autographed picture of Mr. Cuomo for a birthday present for her, but instead the governor invited her, her son-in-law, and her daughter for a personal audience with him.

The two became frenemies of sorts, occasionally exchanging letters. Mr. Cuomo once even hosted Mr. Rosenfeld’s starstruck elderly mother-in-law in the governor’s office. Mr. Rosenfeld had directed his Capitol reporter to ask for an autographed picture of Mr. Cuomo for a birthday present for her, but instead the governor invited her, her son-in-law, and her daughter for a personal audience with him.

On the other hand, Mr. Rosenfeld writes that he drew up an ethics code that ordered his TU minions to even pay for their own coffee when meeting with sources! But what’s good for the general isn’t necessarily good for the grunt, even in journalism.

Speaking of the Albany political machine, Mr. Rosenfeld drops William Kennedy into adjoining sentences with Mr. Melville and Mr. James as fellow Albanians. Mr. Kennedy wrote Ironweed, which won the Pulitzer in 1984 and is the centerpiece of his “Albany Cycle” of novels. The mythologized machine appear in his books and was also the subject of some of his articles when he reported for the TU years before Mr. Rosenfeld was supposedly enlisted to whip it into fighting shape.

So Mr. Rosenfeld drafted Mr. Kennedy, who’s ninety-one and still living outside the city he’s made a career of, to write the foreword for Battling Editor, presumably for his literary firepower. But at just over a page long, Mr. Kennedy is as banal as he is brief:

Harry’s book is often about tough decisions, and it stands out as a handbook on how to live an ethical life in the news business right now. Is it possible to tell the truth all the time? Sometimes. But this is an instructive narrative—especially today when the truth is such a rare commodity in the White House and Congress, and the financially beleaguered press is itself under threat as an enemy of the people.

That truth is a rare commodity not only in the White House and Congress, but every bit as much in the rapidly dwindling newsrooms that helped form Mr. Kennedy and Mr. Rosenfeld (and me), seems beyond both of them.

The press under threat as the enemy of the people? Both men seem blind to the evidence that the majority of voters have plainly judged: the press, for the most part, has betrayed its mission (as defined by them both) to at least try to take an unbiased look at the facts and tell the truth, even when it’s not even close to elusive.

Ironically, Mr. Kennedy’s and Mr. Rosenfeld’s former employer in Albany, Hearst, was the unabashed creator of fake news. Yellow journalism not only helped build Hearst Castle, but lead directly to the Spanish-American War. In his previous memoir, Mr. Rosenfeld says that he only considered signing on with the media titan because it had reformed its “right-wing” ways. In Albany, he could finally be—guilt-free—a Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee. Charles Foster Kane would be proud.

In the epilogue of his current memoir, however, Mr. Rosenfeld reminds me not of the Orson Welles who pines for Rosebud, but of the Orson Welles who warns of a fictional otherworldly invasion in “The War of the Worlds.” For instance, Mr. Rosenfeld writes:

More than ever in many generations, these days the nation stands imperiled. The press is under calculated political assault from an ascendant right wing for its very independence at the same time that its strength is sapped economically.

I write these words in a day when the president undermines the press because it has the temerity to decline participation in his amen chorus.

So it’s a right-wing conspiracy all over again, full of little green (with envy) men. It’s the president—not its own lack of ethics—that “undermines” the press, according to Mr. Rosenfeld. In other words, it must be coddled no matter how arbitrary, fierce, and frequent its tantrums. However, I suspect that he’d vehemently deny any hint of the press’s unabashed prostration before Mr. Obama and his administration.

Facts are not only stubborn things, they’re stealthy too. And at least one of the so-called facts in Battling Editor seems to have gotten the better of the editor emeritus (he still holds the title of the TU’s editor-at-large). He ends his book with what sounds like a rousing farewell speech to the troops—the very last sentence of his epilogue—a bold command to re-educate their supposed attackers:

Thomas Jefferson’s epic instruction—”Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty”—must be firmly fixed in hearts and minds and affirmed by behavior.

The quote certainly sounds like it might’ve been said by the Sage of Monticello, one of the creators of the United States of America and one of its greatest and most admired presidents, and few would argue, the most cultured and intelligent. It’s a potent justification of journalism as the country’s and democracy’s chief protector, its unofficial fourth estate. It’s dramatic and authoritative, deriving great power from its august composer.

It’s also apocryphal. It’s untrue. Mr. Jefferson never said it. So affirms the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia and the research librarian of the Jefferson Library at Monticello.

And what’s worse, what Mr. Jefferson did actually say about newspapers, in the end, was the exact opposite in sentiment of Mr. Rosenfeld’s false quote. In fact, Mr. Jefferson would be the last one to be surprised by all this.

Here’s initially what Mr. Jefferson actually did say:

. . . and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

At the time he wrote that, he was forty-three. He was just about the same age Mr. Rosenfeld was when five burglars broke into the headquarters of the National Democratic Committee at the office building that gave the scandal its iconic name (and a litany of future riveting mishaps, like Deflategate) and catapulted him, along with Mr. Crowninshield Bradlee and “Woodstein,” into modern folklore.

But with two more decades of political servitude (which is how Mr. Jefferson eventually came to see his time in government), he radically changed his mind about newspapers. This reflected what he’d learned after having served all but one of his eight years as president, during which he’d orchestrated the rapid territorial expansion of the United States that would help make it the most powerful nation on earth. By this time he was sixty-four—only a few years shy of the age Mr. Rosenfeld was when his Hearst overseers, as he relates it, summarily retired him as Editor of the TU.

A more seasoned and enlightened Mr. Jefferson now says:

Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle. The real extent of this state of misinformation is known only to those who are in situations to confront facts within their knowledge with the lies of the day.

And in the same letter, a few sentences later:

I will add, that the man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them; inasmuch as he who knows nothing is nearer to truth than he whose mind is filled with falsehoods & errors. He who reads nothing will still learn the great facts, and the details are all false.

These excerpts sound something like tweets from the current president (especially “polluted vehicle”). If the identity of the above letter writer were unknown, those with acute Trump Derangement Syndrome would mercilessly mock whoever it was as a MAGA-hatted press-hating deplorable.

That such an esteemed editor as Mr. Rosenfeld would fail to carefully consider such context, let alone the quote—in a nonfiction book, one in which truth is a major theme—seems to prove Mr. Jefferson’s case two centuries later.

In fairness, Mr. Rosenfeld admits that he’d had trouble with his memory while writing his previous memoir, let alone this one. But according to his acknowledgments section, he had plenty of editing help, both from former colleagues and his publisher, State University of New York Press. I’m not saying Mr. Rosenfeld and his editors deliberately used a false quote. But they apparently let it slide by unscrutinized, since it took me only a few minutes to check it on the internet.

Predictably, a fresh full-blown case of the nationwide epidemic presented itself at Mr. Rosenfeld’s appearance at the Albany Institute of History and Art. During a question-and-answer session, a middle-aged woman introduced herself to Mr. Rosenfeld by saying she was so-and-so’s daughter, presumably someone he knew. Then she fell into a stream-of-conscious rant:

. . . And (pause) everybody I know hates Trump, understands intellectually how we got here, but still can’t believe it. Umm, when I hear somebody say (pause) that, bad things about Barack Obama, I, I just want to throttle them! (laughter). And so, it almost feels like, you know, there’s, there’s no control. So (pause), all my reading and everything else, (whining tone) what do you do when (pause) you just (pause)—it does come between you. I don’t want to be with those people. They’re not the same. It’s not (pauses) the same (slight laughter).

“I tell you, you can’t overcome your feelings on that, you’re not going to cure them,” Mr. Rosenfeld gravely counseled in his Bronx accent. “Uh, uh, yes, I think we have reached that point in our society. Um, it’s a pity. Uh, we, we should strive to overcome that. Uh, we should be able to talk to each other, even with people we profoundly disagree . . . I mean, um, uh, I think we should give it a special effort to talk to people that we disagree with . . . It’s worth trying.”

Her husky voice now sounding like a teenager’s:

“Well I’ll try but I don’t know how to get it out of my head that they’re stupid.”

Burst of laughter.

“They think you’re stupid,” Mr. Rosenfeld shot back.

Having not yet obtained a copy of his latest memoir, I was guardedly encouraged. After reading it, his carefully measured advice for this terminally ill-willed woman doesn’t seem to have been prescribed by the same person who wrote the jeremiad in Battling Editor’s epilogue.

Another questioner seemed to remind Mr. Rosenfeld of the title of the book he was there to tout. An older woman said she was following up on a man’s earlier question about how newspaper editors make decisions. In a determined even voice, she went on:

“. . . How can the community influence the paper in, in taking on an issue and actually going forward? You answered his question with uh, dismissively actually, telling him, ‘Well the editor made that decision.’ How can we get the paper to take on an issue that, that we believe affects the community?”

“Well, people usually communicate with the editor to uh, to uh (pause), make their point,” Mr. Rosenfeld said.

“But, but what if they say no? Are there other things that one can do, you know, other kinds of advocacies?”

“No.”

“Where do you press the button?”

“You can burn, you can burn yourself up,” Mr. Rosenfeld suggested, talking over her. “You could go out to south—”

The last word—undoubtedly “Vietnam”—was mostly drowned out by laughter, which lasted an uncomfortable (at least for me) five or so seconds.

In case the interloper didn’t get it, as if Mr. Rosenfeld were dressing down some clueless cub reporter or letter-to-the-editor writer, he taunted:

“Are you less a person than a Buddhist in Saigon? (his voice rising in pitch) What are you telling me? (pause) I mean, if you can’t convince somebody, you can’t convince somebody. (pause) I don’t have any sympathy.”

More laughter.

If it’s true that the great unbylined have contempt for the press now more than ever—though it’d be hard to outdo Mr. Jefferson’s, and he was probably far from alone—I think this little exchange clearly shows why. For all his talk of impartiality, Mr. Rosenfeld seems, in person and in the book, every bit as imperious.

Back between hardcovers, he shows that he’s no less likely than the people he probes to bend over backward for a dubious friend. While he doesn’t quite cover up for them, he certainly downplays their questionable behavior compared to others not as blessed to have such well-positioned connections.

One such pal of Mr. Rosenfeld’s is Sol Wachtler, the notorious former New York state chief justice. In 1992, while sitting at the head of the state’s highest bench, Mr. Wachtler was convicted of blackmailing his mistress (a stepdaughter of his wife’s uncle) with obscene photos and threats, including saying he was going to kidnap her fourteen-year-old daughter. Because she had apparently spurned him for a younger lover (an attorney), Mr. Wachtler also sent her harassing letters threatening to ruin her, had confidential files pulled on her boyfriend, lied to the authorities, and even sent her daughter a condom. He was sixty-two at the time, had been married for four decades, and had four grown children; the woman who spurned him was forty-five. He resigned and was indicted. Mr. Wachtler and his attorneys claimed he was mentally ill, but the jury saw through it. He spent more than a year in prison. He was disbarred but, incredibly, his law license has since been reinstated. (They don’t call it the Empire State for nothing.)

In his book, Mr. Rosenfeld refers to Mr. Wachtler four separate times, but only in one of them does he say anything about his friend’s egregious conduct while presiding over the state’s most important cases. A TU reporter called him while he was at the symphony and told him about a breaking story:

His astonishing news was the arrest of Chief Judge Wachtler. The charge was harassment of his ex-lover and her daughter, including extortion of money. The scandal and trial lead to his resignation and Governor Cuomo’s selection of Judge Judith Kaye to lead the court. As with Wachtler, the new chief judge and I developed a close working relationship . .

The lengthy paragraph continues, but without Mr. Rosenfeld further describing the tawdry case—as if the Wachtler scandal wasn’t one of the biggest bombshells in New York state legal history and not worth any more space. Instead, in an 81-word paragraph right before his snippet about Mr. Wachtler’s precipitous downfall, Mr. Rosenfeld rhapsodizes about the “outstanding jurist,” his “noteworthy decisions” (including “making spousal rape a crime”), and a “brilliant future” as governor or maybe even president! The encomium ends by gushing: “His professional attainments were reinforced by his good looks and an infectious friendly manner.”

Case dismissed! Propaganda wins! If not quite fake news, it’s far from just, compared to Mr. Rosenfeld’s pillorying of Jim Coyne.

.JPG)

Why do I believe such things were never reported about Mr. Coyne? I’m pretty sure Mr. Rosenfeld wouldn’t have hesitated to tell us all about Mr. Coyne’s perversions if they’d been documented as in Mr. Wachtler’s case, since the conscientious editor scrupulously catalogs Mr. Coyne’s drinking, gambling, and even letting his cronies fill up their gas tanks at the county pumps. Mr. Rosenfeld even dutifully tells us how long Mr. Coyne spent in prison, and even quotes him at his sentencing.

What I’d like to know is how many of the state’s most pressing cases in the state’s highest court may have been prejudiced by an unhinged vindictive character like Mr. Wachtler? How many other opponents and women did Mr. Wachtler harass? What would Mr. Jefferson say (a common refrain at the university he created when I was a student there) about Mr. Rosenfeld’s soft-pedaling and praising away his powerful pal’s serious crimes?

Then there’s Mr. Woodward, whom Mr. Rosenfeld counts not only as a colleague but a friend. In Battling Editor, Mr. Rosenfeld tells us that he invited his most successful protégé to give a pep talk in 2008 to the admiring troops on the northern front (which was duly reported in the TU the next day).

Mr. Rosenfeld also informs us, in an attempt to show his evenhandedness, that he interviewed his former point man about the controversy engulfing Mr. Woodward’s 1987 book VEIL: The Secret Wars of the CIA, 1981-1987. Besides his use of the problematic “Deep Throat” in Watergate, VEIL has perhaps brought down the most damning criticism of all on Mr. Woodward.

About VEIL’s climactic ending, troubling questions abound: Did Mr. Woodward slip past the CIA guards to speak alone to their gravely ill director, William Casey? (Mr. Casey’s wife didn’t think so, and after the book was published, President Reagan, in his diary, called Mr. Woodward a “liar.”) Were Mr. Casey’s words clear and was his nod confirmation that he knew from the beginning that sales of arms to Iran were diverted to the Nicaraguan Contras? Why didn’t Mr. Woodward write this gigantic scoop for the Post, where he worked at the time (and still does), instead of waiting nearly a year to publish it in his book?

Unsurprisingly, Mr. Rosenfeld finds for Mr. Woodward.

He says Mr. Woodward had proven to him in the past that he was trustworthy: “He would not make up a visit and a conversation. It was much more likely security around the bed-ridden Casey was less thorough than the authorities claimed.”

But the wily longtime editor did doubt Casey’s so-called confirmation: “Whether Casey nodded affirmatively, only Casey could say for sure, I concluded.”

Not to worry—according to Mr. Woodward’s old mentor, that was the very reason his enterprising discovery didn’t appear in the Post:

Although insufficiently lucid for his newspaper, Woodward thought it was appropriate for the book. In the context of the fuller story recounting Casey’s activities and his personality and character, he deemed it dramatically relevant.

(I suspect that Mr. Rosenfeld means the information, not Mr. Woodward, was “insufficiently lucid.”)

Context, an element Mr. Woodward has been accused of distorting in the past, is supposed to help clear the air, not clog it up more. “Dramatically relevant” but not truthfully relevant? So in Mr. Rosenfeld’s warped view, a book of nonfiction can be embellished like it was Hollywood and not Washington. Just don’t publish it in his prized newspaper. The problem with Mr. Rosenfeld’s sophistry is that Mr. Woodward wasn’t a spy novelist writing for Simon and Schuster. At least that’s the implication of VEIL’s description as nonfiction, and certainly what book buyers expect and deserve.

It’s enough to make a New Journalist blush, but apparently not an old one.

Read more in New English Review:

• Days and Work (Part One)

• Fond Memories of a ‘Repressive Tolerance,’ as Marcuse Called It

• The Insidious Bond Between Political Correctness and Intolerance

Indeed, at no time does Mr. Rosenfeld ever seem to hold his own ranks accountable, meaning newspapers for the most part, though he’s committed to doing so to most others. In his epilogue, he points to the cyber hoards—”the ill-intentioned and haters,” those for whom “objectivity in news gave way to clearly partisan interpretations of it.” No doubt the internet has unleashed a latent anger on both political coasts. Some of it, however, is understandable. That he fails or refuses to acknowledge that his own hallowed MSM, now as distrusted as the CIA, has also been grossly and shamelessly biased, is just another blatant example of it.

But in Mr. Rosenfeld’s black-and-white world, editors and reporters are rarely, if ever, “ill-intentioned” or “haters” or “partisan.” Like the “outstanding jurist” and felon Mr. Wachtler, it all depends on how well Mr. Rosenfeld knows and likes you.

The First Amendment prohibits Congress from enacting a law “abridging” the freedom of speech or of the press, and rightly so. But it’s not a one-way street lined with only news organizations. It doesn’t say people must buy, figuratively and literally, what the press is selling, especially if it’s defective and negligent. Nor that the president, whether Mr. Trump or Mr. Jefferson, must tolerate whatever uncivilized and underhanded behavior it feels like indulging in.

What Jesus once said to the scribes and their hypocritical bosses of his time one might say to today’s press: “Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel.”

Thanks to Mr. Jefferson, not only the press but the people they’re supposed to inform enjoy the same right to speak and write what they believe to be the truth, based on the available evidence and facts. Now that technology has made that vastly easier for the ink-freed wretch, perhaps that’s why the newspaper buildings Mr. Rosenfeld spent his working life in are every day becoming more and more like whitewashed tombs for the ethically dead.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

Jeff Plude, a former daily newspaper reporter and editor, is a freelance writer. His work has appeared in the San Francisco Examiner (when it was owned by Hearst), Popular Woodworking, Adirondack Life, Haight Ashbury Literary Journal, and other publications.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link