by Norman Berdichevsky (April 2020)

De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill On Sea, East Sussex

The term bellwether derives from the practice of tying a bell around the lead sheep to guide the flock to grazing rounds and back home. It applies to the seaside town of Bexhill in East Sussex on the English Channel coast where I now make my home after relocating from Florida last year. Little did I know at the time how much I would discover about the town’s many innovations, its progressive and non-conformist leaders in setting social and political trends as well as architectural achievements that won international recognition. Variously styled as “modernist,” “streamlined” architecture with curved forms and art deco stylistic features in the Bauhaus tradition were features used to achieve the success of the “Pavilion,” a striking municipal exhibition hall located in the town’s center. It was hailed as the UK’s first public building constructed in the “Modernist style,” a pioneering structure of steel and concrete to provide accessible culture and leisure for the people of Bexhill, to regenerate the site and attract visitors.

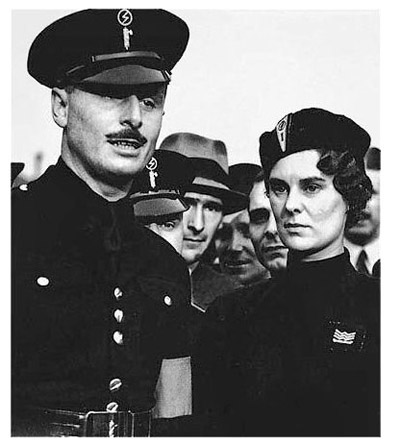

The Pavilion succeeded in essentially transforming an obscure seaside town with the reputation of having been a notorious smugglers’ den for French luxury goods in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Later, the residential choice for many among the elite and conservative upper classes parading their wealth ostentatiously, the playground of devotees of smart racing cars, and a popular retirement venue of many former civil servants and veterans of the armed forces from around the British Empire. Yet by 1936, it had made headlines all over the country as the site where the local leadership responsible for the De La Warr Pavilion project had made a demonstrative stand against the vile anti-Semitism of The British Union of Fascists and their leader, Sir Oswald Moseley, the man British intelligence considered to be a likely candidate to be installed as head of government by a pro-Nazi regime if the Germans had won the war.

Until the 20th century, the town had lagged far behind nearby Hastings (of 1066 fame), Eastbourne, Margate, and Brighton (see map) all of which had incorporated popular amenities into their town planning such as exhibition and music halls, theaters, piers, aquariums, bowls and tennis grounds, and penny arcades, acquiring reputations as popular tourist and recreational venues in the summer. Fortunately, a series of dynamic community leaders functioning as mayors who owned much of the beachfront area of Bexhill with the noble title of Earls of De La Warr (pronounced like the American state “Delaware”) devoted themselves to the cause of civic improvement to push the town forward. They traced their ancestry to the head of an English rescue mission to save the first English colonists of Jamestown, Virginia and by the 18th century had also acquired much of the land in the present adjoining American state of that name. Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr was simply named as “Lord Delaware.” He served as governor of the Jamestown Colony in Virginia, and the Delaware Bay was named after him. The state of Delaware, the Delaware River, and the Delaware Indian tribe were all called after English “lord.”

Read more in New English Review:

• Tom Wolfe and the Ascent of Mass Man

• Faraway Places

• On the Beach, On the Balcony

• COVID-19, Iran, and The Middle East

The seventh Earl De La Warr set in motion the first step by construction of a sea wall in 1883 launching a building boom and officially added the suffix “on-Sea” to the town’s name to emphasize the coastal nature of the new resort. He was already enormously wealthy and controlled much of the land between Hastings and Bexhill. His son, “The Eighth Earl” (Gilbert Sackville) ensured that the “high tone” of the town would be preserved by banning whatever he considered “rowdy behavior.” He launched an accelerated “golden age” of building that included the major hotels, two golf courses and the “Kursaal Pavilion” (modeled on similarly named German leisure and bathing resorts to provide high-class leisure and entertainment). It was the first place in the country to show motion pictures. He also put Bexhill on the map as the center of motor racing in the UK, with world speed records set in 1902-04 adding prestige to his position as chairman of the Dunlop Tyre Company. His wife Muriel also set a new model of radical and refined chic interests with a commitment to the suffragette movement, and support of trade union rights. She also dabbled in theosophy, encouraged “mixed bathing” (men and women allowed to swim together in the sea) and cycling.

All these activities and construction work cost a great deal of money and came close to bankrupting the Earl who managed to salvage a deal engineered with the help of his father who arranged with builders to receive a large portion of the land the Earls owned in return for the work they carried out. Following World War I, many of the wealthier tourists who had frequented the Sussex seaside towns preferred locations on the continent such as Biarritz. The genesis of the Bexhill De La Warr Pavilion project lay in the attempt to compete with this foreign competition and offer similar amenities. The depression of the 1930s and better rail connections from the Midlands and further North bypassing London in order to reach the Sussex coast provided a major stimulus. The government also allowed more autonomy than in the past for local councils in the region to spend and borrow for buildings to provide entertainment. A development report prepared for the town council urged construction of new attractive amenities connected to the arts in the center of Bexhill.

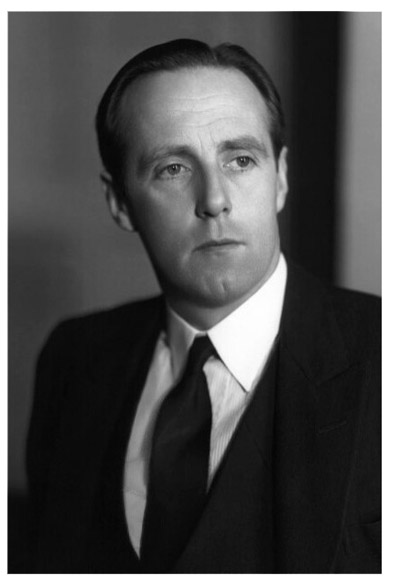

Fortunately, the new 9th Earl De la Warr (born in 1900 as Herbrand De La Warr) but known from his youth to friends as “Buck,” took up the reins of his distinguished family and carried his family’s tradition of progressive innovation much further. He became a leading light of the socialist movement and joined the Labour Party in the British House of Lords, becoming the first hereditary peer to do so. He won election as mayor and managed to convince the majority of voters of the essential need to create a world class attraction in the form of a striking multi-purpose building to serve the entertainment needs, and arts “in touch with the modern ideas of architectural development.” Breaking with the Victorian and Edwardian architectural styles in vogue at the time (1870-1912) using heavy brick work, stone and wood, the proposed Pavilion was highly innovative. A design competition was scheduled with a monetary award provided to the winning entry. In total, 230 entries were submitted. All entries bore a code identifiable as the work of an entrant only after the selection process had been completed and a winner chosen.

Fortunately, the new 9th Earl De la Warr (born in 1900 as Herbrand De La Warr) but known from his youth to friends as “Buck,” took up the reins of his distinguished family and carried his family’s tradition of progressive innovation much further. He became a leading light of the socialist movement and joined the Labour Party in the British House of Lords, becoming the first hereditary peer to do so. He won election as mayor and managed to convince the majority of voters of the essential need to create a world class attraction in the form of a striking multi-purpose building to serve the entertainment needs, and arts “in touch with the modern ideas of architectural development.” Breaking with the Victorian and Edwardian architectural styles in vogue at the time (1870-1912) using heavy brick work, stone and wood, the proposed Pavilion was highly innovative. A design competition was scheduled with a monetary award provided to the winning entry. In total, 230 entries were submitted. All entries bore a code identifiable as the work of an entrant only after the selection process had been completed and a winner chosen.

The winning entry was submitted by two Jewish architects, Erich Mendelsohn, a proponent of the art deco style and identified with the Bauhaus movement who had left Germany on March 23, 1933, the day after Hitler assumed power and had been in the country for only ten months and Serge Chermayeff, born in Russia who had emigrated to the U.K. in 1923. Mendelsohn was already internationally famous for his work on the Mosselhaus newspaper office and print shop in Berlin in 1923 and designing buildings in Palestine, the new Hebrew University, The Hadassah Hospital on Mt. Scopus in Jerusalem, as well as the private home of Israel’s future president Chaim Weizmann in Rehovot.

The two had formed a partnership in 1933. The British Architects Journal (vol. 79, February 1934) had praised the choice . . . “Mr. Mendelssohn and Mr. Chermayeff have succeeded in making their solution tell on sight by their directness of approach to the problems involved” and . . . “It appears to us that the award at Bexhill may have far-reaching effects on the progress of contemporary design in this country.”

Their design proposed three structural units: an entertainment hall, a restaurant and a main entrance hall, all permitting the flow of visitors through the pavilion but allowing for separate use of each, if required, and flanked by two spiral staircases allowing an ascent to the balcony from where striking views of the town in front and the sea in back were afforded.

The response to the award to two “foreigners, alien Jews” was immediate from Fascist leader Oswald Moseley, a former socialist (like Mussolini) and a personal friend of Buck De la Warr. Moseley’s journal, Fascist Week featured the response claiming that the award was an outrage and an affront against British architects and that the Architecture Journal had betrayed its members. It claimed that the major concern of native-born architects was to protect their interests as Britons, and not “aliens who had been kicked out of their home countries.” The mayor responded, defending the absolute fairness and anonymity of the selection procedure and stated in the Architect Journal that if Mendelsohn were to stay in Britain and apply for naturalization, he was given to understand that the British Architects Professional Association “would be honored to consider him for the bestowal of the highest honor the profession could give.”

Naturally, the Bexhill Taxpayers Association was concerned about the rising costs of the project which had escalated from an initial 50,000 to 80,000 pounds. With the encouragement of the mayor, the taxpayers backed the project after a two day townhall meeting and decided to apply to the Ministry of Health for a loan to cover the cost and Mendelsohn introduced a few minor revisions scaling down non-essential elements of the design such as an outdoor swimming pool, pergola and bandstand. Occupying a prominent place at the townhall meeting was a three-dimensional model of the scheme that won many hearts. Many residents were impressed by the absence of interior columns due to the use of welded steel that increased strength enabling greater loads to be placed on the joints and the use of thinner more streamlined walls and floors. The loan was approved to be repaid over fifteen years.

Naturally, the Bexhill Taxpayers Association was concerned about the rising costs of the project which had escalated from an initial 50,000 to 80,000 pounds. With the encouragement of the mayor, the taxpayers backed the project after a two day townhall meeting and decided to apply to the Ministry of Health for a loan to cover the cost and Mendelsohn introduced a few minor revisions scaling down non-essential elements of the design such as an outdoor swimming pool, pergola and bandstand. Occupying a prominent place at the townhall meeting was a three-dimensional model of the scheme that won many hearts. Many residents were impressed by the absence of interior columns due to the use of welded steel that increased strength enabling greater loads to be placed on the joints and the use of thinner more streamlined walls and floors. The loan was approved to be repaid over fifteen years.

The dedication ceremony on December 12, 1935, attended by the heirs to the throne, the Duke and Duchess of York (later to be the reigning monarchs George VI and his Queen Elizabeth, mother of the present queen) at which the mayor delivered an address widely quoted, elevated Bexhill and its Pavilion into the national consciousness.

“I mark a great day in the history of Bexhill . . . How better could we dedicate ourselves today than by gathering round this new venture of ours, a venture which is going to lead to the growth, the prosperity and the greater culture of our town, part of a great national movement to virtually found a new industry—the industry of giving relaxation, pleasure, culture which hitherto the gloom and dreariness of British resorts has driven our fellow countrymen to seek in foreign land.”

Read more in New English Review:

• Weaponized Words

• Destroying Civilization to Save It

• Mother Jones Smears and Spreads Conspiracy Theories

These endorsements humiliated Mosely who felt that the presence of the royal heirs to the throne and the socialist views of the mayor (a distinguished member of the House of Lords and linked with “alien” Jews) challenged his antisemitism as a legitimate cause. He felt it would deprive him of part of his appeal to working class Brits in the East End of London. He didn’t care to appear in Bexhill himself but sent a squad of Blackshirt followers to the town in July, 1936 to demonstrate against the Pavilion. Scuffles broke out when the fascists were set upon by an unruly crowd and chased away. The police were summoned to break up the demonstration that provided no glamour for Moseley’s cause.

These endorsements humiliated Mosely who felt that the presence of the royal heirs to the throne and the socialist views of the mayor (a distinguished member of the House of Lords and linked with “alien” Jews) challenged his antisemitism as a legitimate cause. He felt it would deprive him of part of his appeal to working class Brits in the East End of London. He didn’t care to appear in Bexhill himself but sent a squad of Blackshirt followers to the town in July, 1936 to demonstrate against the Pavilion. Scuffles broke out when the fascists were set upon by an unruly crowd and chased away. The police were summoned to break up the demonstration that provided no glamour for Moseley’s cause.

In 1938, “Buck” De La Warr, who had presided over the Pavilion cause, and his wife attended a gala celebration in Paris upon the election to the prestigious French Academy, of a previous guest of his in Bexhill, French writer Andre Maurois. “Buck” delivered a heartfelt address explaining how France and Britain were natural allies as the “joint defenders of democracy, freedom and civilization.” Like so many other veterans of World War I, the Earl had emerged from the trenches dedicated to the cause of pacifism and demilitarization in the future, only to reluctantly have to change course when he fully realized the enormous evil of Nazism and the futility of further compromises and appeasement. He declared,

”We have our treaty arrangements and common interests and these things bind us together indissolubly. But above these material ties is the determination of the common man and woman in both countries to hold firm to, and if need be, defend the things we all hold dear. We assert the right to read the books, and see the pictures and hear the music of artists, not only of our own but of all races, including Jews, and finally the right of human beings to enjoy and develop the more decent and friendly things in their nature.”

More than eighty-five years after its inception, “The De La Warr Pavilion” remains the most prominent feature of the town surrounded by a wealth of traditional Victorian and Edwardian style buildings. It stands for much more than an achievement in architectural design. It is a tribute to the best in British values of fair play, integrity, and a delightful bit of eccentricity and non-conformism. I am proud to live here and tell its story.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

______________________

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast