by Dennis P. Chapman (November 2022)

Untitled (Garden of the Gods), Ward Lockwood, 1932-33

On October 12th, 2022, President Biden established the Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument near Leadville, Colorado, pursuant to the Antiquities Act of 1906.[1] This is President Biden’s first such proclamation and, like those made by President Obama, it has been controversial. Environmental groups,[2] Colorado veterans,[3] and the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain bands of the Ute tribe[4] all welcomed the action, while energy industry representatives,[5] several Republican members of Congress, the Utah-based band of the Ute Indian Tribe, and a Denver Post contributor panned the move. Congressional opponents complained that, while “Camp Hale and our service members that were stationed there made important contributions to World War II” and should be recognized, “extremist environmentalists … are seeking to hijack this historic place” to impose draconian restrictions on timber harvesting and mining in the area.[6] An op-ed in the Denver Post objected to President Biden’s mismanagement of the oil and gas industry and thus jeopardizing the royalties from which provide funding for our national parks,[7] while the Utah Ute Indians have been critical of the Biden administration on a number of fronts.[8]

Consternation over a new national monument may be justified given the extensive size of such monuments dedicated in recent years, the excessive restrictions on the timber and energy production that have accompanied new proclamations, and the tenuous state of funding for our national parks. But it will be a pity indeed if we allow such controversies to overshadow the historical importance of Camp Hale, or to further obscure the heroism of the men who trained there. That a politician might establish a new national monument out of mixed and inscrutable motives is so self-evident as to be beyond reasonable debate. Yet I hearken back to the Apostle Paul, who rejoiced in those who preached “Christ even from envy and strife,” knowing that even if they “proclaim Christ out of selfish ambition rather than from pure motives” they proclaim Christ all the same.[9] Important questions as to the geographical scope of the monument and the extent of logging and mineral extraction permitted on it can be re-adjudicated going forward. For the moment, it is enough that this important site finally has the recognition it deserves.

While comparatively few people have heard of Camp Hale, many Americans are familiar with places like it. Camp Hale was one of the many small posts and installations across the country that housed and trained US Army soldiers—Regular, Reserve, and National Guard—throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Some, like Michigan’s Fort Custer about 14 miles from Kalamazoo, continue to host and train soldiers to this day, while others like the historic Madison Barracks at Sackets Harbor, New York—nestled on the very shore of Lake Ontario—have long since lost their military role but have been preserved and repurposed to other functions. Camp Hale enjoys neither distinction. Built in 1942, it functioned for only three years, being deactivated in 1945, its structures cannibalized to support activities elsewhere. Though it was subsequently rebuilt in 1947, a friend of mine who trained there with the Special Forces many years ago found only concrete slabs as a testament to what once stood there. The importance of Camp Hale—what makes it sacred ground worth preserving and commemorating—is neither its nonexistent architecture nor its status as one of many long defunct US Army installations. Camp Hale is important not for what it is, but for who it was that trained there. For Camp Hale is the former home of the US Army 10th Mountain Division, which would win glory and acclaim during the Italian Campaign in World War II, and afterwards on battlefields and in operational areas as far flung as Somalia, Haiti, and Afghanistan.

The Inception of the US Mountain Troops

Formation of mountain or any other specialist troops was a matter of some controversy in the US Army in the 1930s and early 1940s; because Congress’s miserly prewar Army budgets left little money available for such pursuits, providing conventional troops with appropriate training on an as-needed basis was deemed the only feasible option for meeting specialized contingencies. This began to change following the Soviet Union’s disastrous invasion of Finland in 1939, as Americans watched the drubbing handed to the Russians in Finland’s harsh winter climate, as well as the poor performance of conventional Italian infantry thrown piecemeal into mountain combat in Albania. Seeing how poorly conventional infantry and armor troops fared in these harsh environments without proper training or equipment, the United States began experimenting with specialized mountain and winter training in the winter of 1940 – 1941. The US Army’s first dedicated mountain unit—1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry—was formed at Fort Lewis, Washington in late 1941, and the Mountain Training Center was activated in September 1942 at Camp Carson, Colorado. It was from these tender shoots of winter wheat that the 10th Mountain Division would soon grow.

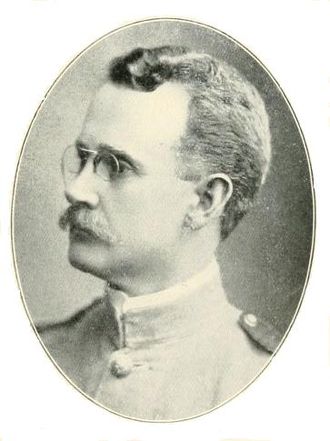

Although the 87th Mountain Infantry commenced training at nearby Mount Rainier shortly after its activation, it soon became apparent that the regiment and the Mountain Training Center needed a dedicated home of their own, not least to escape the officious meddling of the Western Defense Command to which the 87th was subjected at Fort Lewis. Pando, Colorado—a barren wilderness locale a few miles outside tiny Leadville—was selected. Accessibility to road and rail transportation, a roomy valley floor for the camp, and high surrounding peaks made Pando ideal territory for mountain and winter training, but living there was a challenge. Christened Camp Hale after Brigadier General Irving Hale, a Spanish-American War veteran and a founding member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the camp had no amenities in the beginning. Family housing for the officers was located seventy miles away in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and the camp’s geography—essentially a bowl in which the camp itself was the bottom and the surrounding mountains the sides—captured smoke and soot from the 500 coal-fired stoves and the dozen or so trains supplying the camp daily, afflicting the men with the infamous “Pando Hack.”

Formation of the 10th Mountain Division

Upon completion of Camp Hale both the 87th Mountain Infantry and the Mountain Training Center were relocated there, and the Mountain Troops expanded as the 87th filled out to a full-sized regiment and three new mountain units—the 85th, 86th and 90th Mountain Infantry Regiments—were organized. The 10th Light Division (Alpine) was formed from 85th, 86th, and 90th (subsequently replaced by the 87th) Mountain Infantry Regiments at Camp Hale on July 15, 1943, and was re-designated as the 10th Mountain Division in early November 1944.The 90th Infantry had been activated to replace the 87th after the latter was dispatched to the Pacific Theater to participate in Operation Cottage—the expulsion of Japanese forces from Kiska Island in the Aleutians—as part of Amphibious Task Force (ATF) 9. The 90th would have a short stay with the 10th Mountain Division, however. ATF-9 splashed ashore on Kiska in mid-August 1943 only to find the Japanese garrison there gone, having been covertly whisked away in a brilliant naval evacuation. Having thus gotten through Operation Cottage with only a handful of casualties from friendly fire instead of the hundreds expected had the Japanese stood and fought, the 87th returned to Camp Hale and assumed its rightful place in the 10th Mountain Division. The 90th Infantry, thus displaced and stripped of everyone who had received mountain training at Camp Hale, was relegated to obscurity as a replacement training unit. Deactivated forever after the war, the 90th never even acquired its own distinctive unit insignia.

Remarkably, the 10th Mountain Division was not initially conceived by the Army Staff or even by Congress. Instead, the impetus to establish specialized training in winter and mountain warfare came from the mind of Connecticut insurance broker Charles Minot “Minnie” Dole. Although his own military experience was brief, Dole was an accomplished skier, and as president of the National Ski Patrol (NPS) he was deeply involved in the then small American skiing community. Dole’s interest in military affairs was inspired by the Russo-Finnish war. Watching from afar as Finland’s ski-mounted troops pummeled the much larger Soviet invaders, Dole soon realized that the harsh winter conditions of America’s northern latitudes could pose as serious a challenge to military operations here in the United States as they had in Finland. Likely sensing that the US Army was no better prepared to fight in such hostile conditions than the Soviets had been, he soon took it upon himself to lobby both the Army and Congress to establish a winter training program. Dole was remarkably successful, ultimately helping to convince Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to make the first tentative forays into specialized winter training in 1940 and 1941, noted above.

As the Army’s winter warfare project expanded, Dole and the NSP remained intimately involved, actively participating in the Mountain Winter Warfare Board formed to develop recommendations for the training and equipment of Army mountain troops. When the Army finally took the decision to form a specialized division dedicated to mountain warfare, Dole and the NSP took their involvement to another level altogether, contracting with the Army to assume complete responsibility for recruiting soldiers for the division. Unlike other Army divisions, the 10th Mountain and its subordinate mountain infantry regiments would not rely on ordinary volunteers and the draft for its manpower; instead, the NSP set about recruiting skilled skiers and other rugged outdoorsmen who would be equal to the unique rigors of training and fighting in a winter and mountain environment. The inevitable attrition experienced by every military unit made it impossible to man the 10th Mountain Division entirely from the men recruited by the NSP, but this hard core of experts provided the skilled cadre that would impart the necessary skills to those soldiers brought in from elsewhere.

The mountain troops embarked upon a rigorous training program at Camp Hale, weeding out those unable to adapt to the special challenges of mountain warfare; honing the skills of those already experienced in outdoor pursuits; and bringing the new men up to the same standard of competence. The 10th Mountain Division’s preparations culminated in late 1944 with the infamous D-Series exercises, a grueling six-week period of training and evaluation carried out in brutal winter weather conditions on the rugged mountains surrounding Camp Hale. Shortly thereafter the division decamped from Camp Hale in December 1944 for the very different clime of Camp Swift, Texas.

Moving from the sub-zero temperatures of Camp Hale and embarking on a regimen of standard infantry training in the dry heat of Texas took a toll on the division’s morale, especially as rumors began circulating among the men that after all they had been through at Camp Hale the division would be deployed only as ordinary straight-leg infantry. Notwithstanding their angst, however, the flatland interlude at Camp Swift was productive, as shortcomings in the division’s organization and equipment were identified and remedied, and gaps in the Division’s training were filled. In the end, the mountain troopers’ fears were unfounded, as the decision was made by November 1944 to deploy the 10th Mountain to the Mediterranean theater. By January 1945 the 10th Mountain would be in Italy.

Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere

The 10th Mountain Division’s moment would come in February 1945, when it would serve as the main effort in Operation Encore. The key terrain in the 10th Mountain Division’s sector was the Mount Belvedere massif dominating a ten-mile stretch of Highway 64, a route that Allied forces needed in order to penetrate the Apennine Mountains and reach the Po Valley beyond. Allied forces had tried and failed multiple times before to drive the Germans off Mount Belvedere. Now the 10th Mountain Division would try to accomplish what the others couldn’t.

Before the 10th Mountain could move against Mount Belvedere, a preliminary objective had to be reduced first. Just as the Germans were able to dominate the vital Highway 64 from their positions on Mount Belvedere, other enemy units were able to dominate the approaches to Mount Belvedere from positions on an adjacent terrain feature—Riva Ridge—to the west. The 10th Mountain would first have to knock the Germans off their perch on Riva Ridge before they could launch their main effort against Mount Belvedere.

The task of clearing Riva Ridge would fall to 1st Battalion, 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment (1/86IN). As with Mount Belvedere, Allied units had tried multiple times to drive the Germans off Riva Ridge, each time attacking the position from the rear, via Riva Ridge’s gentler western slope. Each time, they had been repulsed. The 86th Regiment would take a different tack—unlike their predecessors, they would boldly storm the position from its nearly sheer eastern face. This presented a problem, however, in that the 86th Infantry, along with the rest of the 10th Mountain Division, had continued to receive fillers during its interval at Camp Swift, none of whom had had the benefit of the mountain training at Camp Hale. The Regiment’s leadership briefly considered leaving these men behind during the assault on Riva Ridge, but soon set about a more audacious plan. Taking possession of a nearby marble quarry as a training ground, 1/86IN put the new men through a crash mountaineering course, with refresher training for the rest. Everyone in the 1/86IN Infantry would climb the face of Riva Ridge.

Operation Encore kicked off with 1st Battalion, 86th Infantry’s attack on Riva Ridge during the night of February 18th – 19th, 1945. In the days prior to the attack, the 86th had reconnoitered the objective and identified the lanes that the attacking troops would follow. Two of these lanes were so steep that a picked force of expert climbers had covertly scaled the cliffs up to 1,500 feet, laying guide ropes and pounding pitons into the rock with muffled hammers that the attacking troops would use to scale the cliffs. All previous attempts to storm the position had come from the western slope, and the Germans considered the steep eastern face unclimbable, especially by Americans whom the Germans did not take seriously as real mountain troops. When those green Americans emerged out of the darkness from that very “unclimbable” eastern slope, the Germans were taken completely by surprise and driven of the ridge. Despite fierce counterattacks, the Germans never regained their position.

While the Germans were focused on retaking Riva Ridge, the rest of the Division launched its attack on Mount Belvedere on the evening February 19th, 1945. Supported by the Brazilian 1st Infantry Division, the 10th Mountain Division spent the better part of the next week in a grinding slog as they fought their way along the Belvedere massif’s southwest to northeast axis. By February 25th, the 10th Mountain Division and the supporting Brazilians had expelled the enemy and consolidated their hold on Mount Belvedere.

Operation Craftsman

Building on the 10th Mountain Division’s victory at Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere as well as advances elsewhere on the peninsula, Allied forces moved to deliver the coup de grâce to Axis forces in Italy with Operation Grapeshot, beginning on April 6th, 1945. The 10th Mountain Division’s part in the effort would commence several days later. With the Brazilian 1st Division on the left, the 10th Mountain Division in the center, and the US 1st Armored Division on the right, the American IV Corps, part of the US Fifth Army, commenced Operation Craftsman—its attack to break through Axis forces ensconced in the Apennine Mountains—on April 14th, 1945. Six days of hard fighting brought the 10th Mountain Division to the final ridge of the Apennines: by the evening of April 19th, the troops of the 10th Mountain Division were overlooking the Po River Valley. The next day, April 20th, 1945, the 10th Mountain Division became the first Allied unit to break out into the lowlands of the Po Valley. Along with the rest of IV Corps and other Allied forces in Italy, 10th Mountain Division now began a rapid dash across the Po Valley to block retreating Germans from reaching the Austrian Alps, where it was feared that they would establish a “southern redoubt” to try and stop the Allied advance. Speed was the order of the day, with the 10th Mountain Division forming Task Force Duff, a fast-moving task force under assistant division commander Brigadier General Robinson E. Duff, charged with facilitating the division’s advance by racing forward to seize key terrain ahead of the line regiments which would reduce the enemy concentrations that Task Force Duff had bypassed. The regiments themselves would speed their own advance by commandeering every sort of vehicle imaginable, from US Army trucks allocated to the division for that purpose, to captured German transport, abandoned horse carts, and captured horses, all used to shuttle the infantry forward to points of enemy contact as rapidly as possible. A new task force was formed—Task Force Darby—after Brigadier General Duff was badly injured and evacuated; the new task force operated under the command of former Ranger commander Colonel William O. Darby, who succeeded Duff as assistant division commander after the latter’s evacuation. Task Force Darby functioned much the same way as its predecessor, rushing ahead of the main body to seize key terrain, thereby facilitating the advance of the rest of the division.

The rapid Allied onslaught overwhelmed the German and Italian defenders; on April 29th Lt. Gen. Max Joseph Pemsel, German chief of staff of the joint Italian-German 1st Ligurian Army, surrendered this unit to US IV Corps, telling IV Corps commander Lt. Gen. Willis D. Crittenberger that he was motivated to surrender in part by his desire to save the German 34th Division from destruction at the hands of the 10th Mountain Division. The end in Italy finally came on May 2nd, 1945 with the capitulation of all German forces there.

After the War

The 10th Mountain Division was redeployed to the United States shortly after the end of hostilities and deactivated on November 30th, 1945. The division would not remain at rest long, however, being reactivated as a training division (shorn of its Mountain designation) at Fort Riley, Kansas in 1948. In 1954 the 10th was reorganized back into a standard combat division, using personnel from the 37th Infantry Division, Ohio Army National Guard, which had previously been mobilized as part of the Army’s expansion for the Korean War. The reformed 10th Division, with its original three regiments—the 85th, 86th, and 87th—was then deployed to Germany as part of Operation Gyroscope, a short-lived Army initiative in which whole units would rotate to and from our overseas garrisons rather than the usual process of rotating individual replacements. In 1958, the 10th Division rotated back to the United States and was deactivated at Fort Benning, Georgia on June 14th of that year.

The 10th Division’s deactivation would mark the beginning of a long hiatus for the 10th Mountain Division; it would also mark the end of the line for two of its three original regiments, the 85th and 86th. In 1957 the Army launched the Combat Arms Regimental System (CARS) to rationalize its system of designating units. Under this system, which remains largely unchanged to this day, selected combat arms regiments would be designated as parent units to be retained in the Army system in perpetuity. All combat arms regimental designations would be drawn from this pool of units thenceforth; regiments not designated for retention in CARS would be inactivated, probably forever. Selection of regimental designations to be retained was done on a point system that took into consideration the service history and honors of each regiment. None of the 10th Mountain Division’s regiments had any combat service credit in the First World War, and their combat service in World War II had been limited to the last year of the war; as such, they were not well placed to make the cut for permanent retention. Only the 87th Infantry was retained as a CARS parent unit; one possible explanation for this is an extra service credit not shared with the other two regiments: the 87th Mountain Infantry’s participation in the Kiska invasion in the Pacific Theater.

The 87th Infantry Alone

While the 10th Mountain Division went into a long dormant period and the 85th and 86th Infantry Regiments slid into oblivion, the 87th Infantry continued in service, spread among various other installations and units. Over the years, battalions of the 87th Infantry apart from the 10th Mountain Division would serve with 2nd Infantry Division in the United States and the 8th Infantry Division in Germany. Two companies would serve in Vietnam, attached to larger Military Police units; and 5th Battalion, 87th Infantry would serve in Panama under the 193rd Infantry Brigade, where it would play an active part in combat operations during Operation Just Cause in 1989. 3rd Battalion, 87th Infantry—then an Army Reserve unit in Colorado—would be mobilized during the early stages of Operation Desert Shield / Desert Storm to secure US military installations in Europe, backfilling the Active Army units stationed there that had deployed to the Persian Gulf. After the Gulf War 4th Battalion, 87th Infantry, assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, would participate in Operation Uphold Democracy to restore Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power after his ouster by a military coup.

Return of the 10th Mountain Division

The 10th Mountain Division was awakened from its long slumber when it was reactivated—with its Mountain moniker restored—at Fort Drum, New York in February 1985, thus beginning the long and arduous process of building a division from scratch. The 87th Infantry Regiment came home, its 1st and 2nd Battalions rejoining the division, where they remain today. Since reactivation, the 10th Mountain Division has become one of the Army’s most deployed organizations. After contributing units to deployments in Honduras, Germany, and the Persian Gulf, the 10th Mountain Division deployed to Homestead, Florida in 1992 to help the state recover from the devastating category 5 Hurricane Andrew that struck the state on August 24th, 1992. Shortly thereafter elements of the division deployed to Somalia as part of Operation Restore Hope in response to the humanitarian crisis caused by that country’s suicidal civil war. Elements of the division, including 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry (one of the units standing in the place of the lost 85th and 86th Infantry Regiments) participated in the fierce Battle of the Black Sea in Mogadishu on October 3rd and 4th, 1993—better known to the public as the Battle of Mogadishu or “Black Hawk Down.”

The 10th Mountain Division has continued its fast paced existence, even more frenetically, since the terrorist attacks of 2001, with numerous, repeated deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere over the past 21 years. If history is any guide, that will continue long into the future.

Camp Hale is sacred ground. The work done there, and under the colors of the 10th Mountain Division since, perfectly embody the initiative, ingenuity, and enterprising spirit that characterizes the best of the American military tradition.

[1] Derek Draplin. “Biden uses Antiquities Act to establish new national monument in Colorado,” The Center Square, October 12, 2022, https://www.thecentersquare.com/national/biden-uses-antiquities-act-to-establish-new-national-monument-in-colorado/article_4f89b504-4a57-11ed-a996-13fd0d1ec0c4.html.

[2] Angela Gonzales and Linda Coutant. “A New National Monument in Colorado,” October 5, 2022, https://www.npca.org/articles/3291-a-new-national-monument-in-colorado.

[3] Alex Rose. “Colorado Republicans push back against Camp Hale ‘land grab,’” KVDR, September 23, 2022, https://kdvr.com/news/local/colorado-republicans-push-back-against-camp-hale-land-grab/.

[4] Brady McCombs. “Utah-based Ute Indian Tribe criticizes Biden’s Colorado monument on ancestral land,” The Colorado Sun, October 13, 2022, https://coloradosun.com/2022/10/13/utah-ute-criticize-biden-monument/.

[5] Draplin.

[6] Letter from members of Congress to President Biden, September 23, 2022, https://boebert.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/boebert.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/Response%20letter%20Rep.%20Boebert%20CO%20Antiquities%20Act%20_2.pdf

[7] Aaron Johnson. “Opinion: Biden’s Camp Hale order highlights his oil and gas mismanagement.” Denver Post, October 12, 2022, https://www.denverpost.com/2022/10/12/joe-biden-colorado-camp-hale-leadville-mistake-oil-and-gas/.

[8] McCombs.

[9] Philippians 1:12-18, New American Standard Bible.

Dennis P. Chapman is a retired US Army Colonel. He served with the 10th Mountain Division as an infantry officer during relief operations following Hurricane Andrew in Homestead, Florida, and during the early stages of Operation Restore Hope, Somalia, 1992-1993. His book, The 10th Mountain Division: A History from World War II to 2005, is forthcoming from Schiffer Publishers in February 2023, and is available for preorder now.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link