by Juliana Geran Pilon (April 2025)

A generation fed on a daily diet of apocalyptic gruel is bound to overindulge in hyperbolic discourse. But obsessing about intractable problems or, worse, about trivialities manifestly unworthy of hysteria, by deflecting attention risks allowing genuine dangers to become more insidious. Like metastatic tumors, eventually it is too late to reverse course. Paradoxically, however, the advanced democracies are especially vulnerable to distraction because success and prosperity breed overconfidence. In fact, potential annihilation is hardest for young elites to fathom. How refreshing, then, to find the much-needed warning against complacency trumpeted by someone born in the same year the Iron Curtain disintegrated, thereby enhancing the chances of its reaching the very constituency that most needs awakening (in contrast to wokening, with apologies for the intended pun).

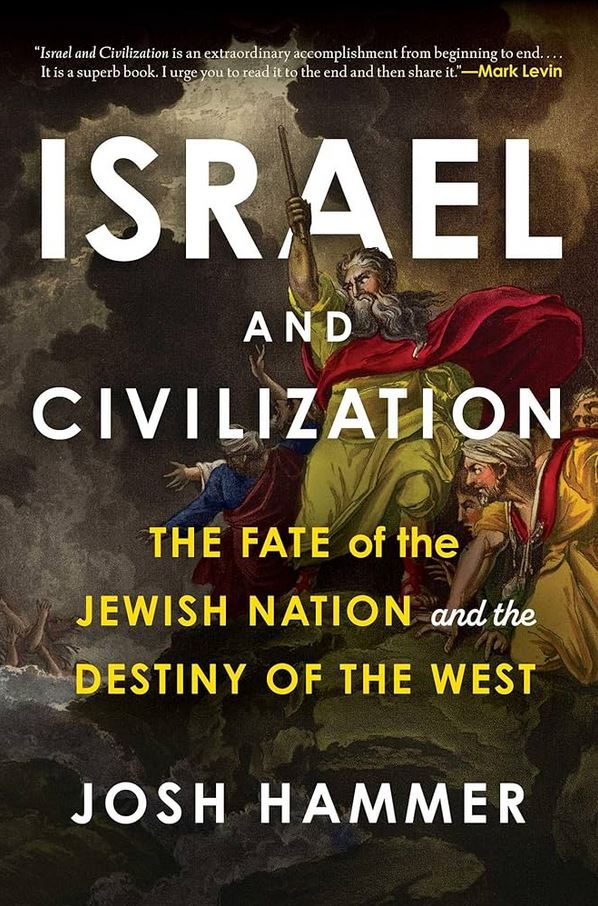

Though stopping short of prophesying doomsday, Newsweek magazine senior editor-at-large Josh Hammer has ample reason to worry about “The Fate of the Jewish Nation and the Destiny of the West,” the subtitle of his ambitiously titled Israel and Civilization. As Jews have throughout history, he trusts eventual redemption, taking comfort in the Jewish people’s long-term survival—and with it, that of Western civilization, which they germinated. But none of us lives in the long-term, and there are no iron-clad guarantees. Even if faith has miraculously strengthened Jews throughout their harrowing history, any generation can come close to extinction, as happened most horribly in the Holocaust.

Which, appropriately, is where Hammer’s book begins. It was before the gas chambers at Treblinka that the question first struck him: How did the world allow it to happen? Then again, with equal intensity, after seeing the horrific devastation from the Simchat Torah Massacre. Stunned by the avalanche of antisemitism throughout the world—most shockingly, in the West—the larger question arises whether civilization itself, the Judeo-Christian world, can survive the appalling meltdown of its core values. Torn by self-doubt and nihilism, incapable of seeing Evil for what it is, did it reach its breaking point?

Which, appropriately, is where Hammer’s book begins. It was before the gas chambers at Treblinka that the question first struck him: How did the world allow it to happen? Then again, with equal intensity, after seeing the horrific devastation from the Simchat Torah Massacre. Stunned by the avalanche of antisemitism throughout the world—most shockingly, in the West—the larger question arises whether civilization itself, the Judeo-Christian world, can survive the appalling meltdown of its core values. Torn by self-doubt and nihilism, incapable of seeing Evil for what it is, did it reach its breaking point?

The situation is unsustainable. Hammer’s verdict is stark: no society can endure unless “it first knows what exactly it is, knows what exactly it stands for, and knows why exactly … it is worth defending and preserving against those who seek to harm or destroy it.” (19-20) The expected precision is not mathematical but spiritual: we must recapture a “belief in the inherent holiness of mankind.” And this is no metaphor: “The simple truth is that what we today call ‘Western civilization’ is the broader Judeo-Christian order. And it all began at Mount Sinai, with God’s revelation to the Israelites and the formation of Israel as the particular Jewish nation.” Simple or not, Hammer passionately believes it as absolute truth.

No, he wasn’t born in a piously Orthodox household but a thoroughly assimilated, patriotic American-Jewish family he describes as “spiritual but not religious.” Like the vast majority of his co-religionists, he grew up idolizing Abraham Lincoln, who had loved the Old Testament and appreciated the indispensable role of the Jewish tradition in shaping Anglo-American political theory and our institutions. As documented in the superb book by Jonathan Sarna and Benjamin Shapell, Lincoln and the Jews: A History, the president who shared a name with the father of monotheism had deliberately sought to complete America’s founding as an “almost chosen nation.” He devoted his life to ensure that the Golden Rule, already enshrined in the Declaration, would be federally enforced.

As Sarna documents in his classic American Judaism: A History, the biblical imperative first arrived with the British Pilgrims, who were seeking refuge from Catholic persecution, followed by Puritans, arriving with families from their temporary Dutch exile. A century later, writes Hammer, Benjamin Franklin and his fellow Founders would see “America as a fundamentally covenantal political project,” a new Israel. Perhaps the greatest admirer of Judaism was Alexander Hamilton, president George Washington’s closest aide and surrogate son, whose work on behalf of the No Religious Test Clause’s inclusion in the Constitution was but one of countless contributions to the cause of liberty of conscience. Unlike previous collections of ethnic and political societies known as empires or kingdoms, America would become one nation, e pluribus unum, reminiscent of the twelve tribes that millennia ago that had constituted Israel.

Hammer does not presume to analyze why and how the American ethos has veered away from its core commitment to biblical values; he focuses primarily on the here and now. But he assumes categorically that “the end-goal of the collective human civilization that we are progressing toward is nothing less than the messianic: the ultimate perfection and wholesome manifestation of God in this world.” (41) Since this sounds so much like progressivist utopianism, there is a chance that it might resonate with his contemporaries. That still leaves the question: how exactly do we contribute to that fulfillment?

For guidance, Hammer turns to Jewish tradition, which holds that only “laws derived from God’s revealed Will are inherently just, morally authoritative, and all-encompassing in providing a comprehensive guide for human behavior.” (53) From the moment that God first gave it to Moses, the Jewish law (Halacha) “has continuously shaped and influenced what Western civilization entails today.” It is not only desirable but absolutely necessary for this to be fully understood for the free world to survive.

It would be absurd to suggest that Hammer implies universal conversion to Judaism as a precondition to salvation; such an outlook is more in line with Islamism. But it does at a minimum require accepting the humane commitment to the sanctity of each individual, so beautifully captured in the first chapter of Genesis: God made man and woman in His own Image. Hence each of us has a spark of divinity; we are to treat one another with respect. If Western civilization forgets this fundamental pillar of its institutions, if it thereby fails to embrace its philosophical ancestry in the Jewish tradition, how can it hope to survive?

“We can praise our own Western accomplishments, or rather the source from which we have drawn the sacred truths that sustain us, only as long as we can give no less credit to the unmatched authority and wisdom of the ancient Hebrew nation,” writes Clemson University Professor Steven Grosby. (240) To which Hammer adds that “Western Christians should recognize that when the Jews are safe, secure, and thriving, so too is the West.” So too for the converse: “[t]here will be no thriving Christian future if there is no thriving Jewish future as well.” (241)

History has repeatedly demonstrated that “where Jews are abandoned and anathemized by secularists, Islamists, and interlopers, Christians are never far behind.” Too many, including some of the best educated people in the world, either don’t realize it or willingly forget. Among those who do are Christians who follow in the footsteps of America’s Founders. Staunch supporters of Israel and Judaism, they have made common cause with Zionists. Yet many in the Jewish community are stubbornly resistant to a Judeo-Christian coalition. Ironically, it is not the Orthodox and Conservative but the more secular, Reform and Reconstrutionist Jews who vote Democratic in disproportionately high numbers, notwithstanding that party’s increasingly pro-Palestinian sympathies.

It is true that religious observance is strongly corelated with support for Israel and for traditional values. Opinion surveys have repeatedly confirmed the close relationship between belief in the biblical God and robust military assistance to the Jewish state. But Hammer lashes out with surprising ire against what he sees as “theologically liberal offshoots of Judaism” for their alleged over-reliance on “reason.” Many a rabbinic eyebrow will be raised to learn from him that “Judaism is not supposed to be ‘reasonable’” (34) – which he explains by saying that Jewish law was never intended to be “a purely logical exercise,” as in taking a SAT test. What isn’t clear is who would suggest such a thing.

Hammer’s hostility to rationalist schools of thought is passionate. These fatally flawed ideologies are dangerous, no good, very bad, “contrasting sharply” with the philosophical basis of Halacha. These include, though not limited to, “utilitarianism, classical liberalism, libertarianism, socialism, and hedonism. Traditional Jewish thought correctly stands against all of these worldviews, instead offering a biblical path forward.” (55 – emphasis added)

A Talmudic retort might be that it all depends on how those notoriously ambiguous isms are defined. Consider the statement that “at the heart of classical liberalism and libertarianism as they have existed and developed since the European Enlightenment is the assertion that individuals should have maximum freedom to act according to their own idiosyncratic will, provided they do not somehow infringe upon the natural or otherwise-bestowed rights of others.” The notion of an “idiosyncratic will,” however, is either redundant (will is always one’s own) or altogether vague. Also, what is an “otherwise-bestowed” right? The answers will differ radically depending on context.

Elsewhere he condemns “liberal [absent either the qualifier ‘classical’ or ‘modern’] and libertarian claims that an individual is simply an atomistic island unto himself, existing in isolation without the unchosen obligations, interpersonal and intergenerational duties, and interdependent boundaries of civic loyalty without which no community or nation can form.” (64) He is right to find such views appalling, but it would have helped to cite someone who holds them. No philosopher immediately comes to mind. Most self-described classical liberals I know keep the nature of their spirituality to themselves. The original ones, who inspired the Founders, were duly pious.

Hammer is on much stronger ground in arguing that “no worldview that abolishes private property or endangers covetousness… can possibly be reconciled with a biblical worldview,” calling it “a complete nonstarter.” (65) So it has been demonstrated, time and again. Actually, socialism and Marxism violate both God’s law and rudimentary economics. Once they emigrate and are no longer fed the Big Lie, people living under Communism have no trouble seeing this reality for themselves. Despite having had no access to religious writings and practice, which the Party outlaws, they grasp the truth at the heart of the biblical tradition that if human beings respect one another and cooperate, they thrive. Hatred and greed corrode.

In the end, Hammer’s conclusion is spot-on, that in America and throughout the Western world, “Jewish and Christian parents must instill in their children, and educators must instill in their pupils, a genuine patriotism, a love of their hearth and home, and a distinctly public spirit and sense of civic mindedness … [alongside] sound republican habits of mind in the hopes that they might contribute, in their own small way, to the saving of America and the survival of the West.” (255) So, indeed, should everyone else, whatever their reasons. God will undoubtedly smile, pleased.

Table of Contents

Juliana Geran Pilon is Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her eight books include The Utopian Conceit and the War on Freedom and The Art of Peace: Engaging a Complex World; her latest book is An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left. The author of over two hundred fifty articles and reviews on international affairs, human rights, literature, and philosophy, she has made frequent appearances on radio and television, and is a lecturer for the Common Sense Society. Pilon has taught at the National Defense University, George Washington University, American University, and the Institute of World Politics. She served also in several nongovernmental organizations, notably the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), where as Vice President for Programs she designed, conducted, and managed programs related to democratization.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

3 Responses

“Do no harm, but if some harm is necessary to prevent greater harm, do as little as necessary and repair the harm done, as necessary.”

Remember, the Golden Rule is bad advice to give masochists.

https://justsayingitoutloloud.blogspot.com/2025/04/swastika-palestine.html?m=1

“Swastika palestine” racist “activism” post Oct/7 atrocities by Islamofascism. [Long list].

A tweet inspired by your piece, Juliana…

https://x.com/JohnCasselman2/status/1910335942319079551/photo/1