The Confusion of Buridan’s Ass

by Kenneth Francis (April 2022)

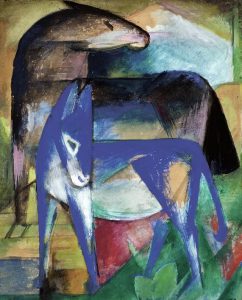

Two Blue Donkeys, Franz Marc, 1912

I’m going to look at the philosophical paradox of Buridan’s Ass and where some confusions in its conclusion might lie. But first I want to briefly comment on an essay I wrote recently on why I believe the brain is not the mind, which posed the following question: At what point in evolution did the atoms in brains develop morals? A thoughtful reader of the essay replied with the following comment:

When man discovered he could choose. In situations where two choices are not equal, when one is ostensibly better, that is more life-affirming than the other, and being cognizant that one choice is better than the other, choosing, that is doing what is right, became synonymous with the moral imperative.

My reply to the reader was:

On Naturalism, humans (and other creatures) never ‘discovered’ they could choose, as they were always endowed with instinctual decision-making attributes based on appetite or survival requirements. Similarly, robots can ‘decide’ when ‘choosing’ to make a move playing chess or other functions. The input of the information into the system [by humans], will influence the moves it makes. But my question is on the existence of freedom of the will and choosing morally, based on objective moral values and duties. On atheism, atoms just blindly bump into one another. Also, be careful using terms such as ‘ostensibly better,’ ‘one choice better than the other,’ or ‘doing what is right’ (on atheism, says who?). Such terms, subjectively, bring great comfort to the psychopaths of this world. (‘The Brain is not the Mind,’ New English Review, March 2022)

This brings me back to the paradox of Buridan’s Ass. I sometimes wonder is the confusion to this paradox due to a category error, similar to the aforementioned comment above on the mind/brain problem, as well as confusion in the term ‘identical’. For those who have never heard about it: Buridan’s Ass is commonly considered to be an illustration of the problem of acting rationally, ‘choosing’, or being endowed with freedom of the will.

Named after the 14th century French philosopher Jean Buridan, but probably originally formulated by ancient Greek philosophers (possibly Aristotle), it goes something like this: Imagine a hypothetical situation where a donkey is both equally hungry and thirsty and, in terms of location, he is placed *equidistant apart, midway between water and food. At this point the paradox assumes that the ass will always go for that which is closer; or does it starve to death due to hunger and thirst because of its paralysis in not being able to ‘choose’? Put simply: It allegedly cannot make any rational decision between the water or food due to the seemingly exact distance of both? (*The definition of ‘equidistant’ is that of equal distance [in most ways], and not ‘identical.’)

But distance aside for a moment, is this a cognitive illustration of a creature lacking high-consciousness reasoning or free will? When philosophers or theologians talk about rationality or free will, they usually refer to it as a moral question, not a preference/decision-making one; thus, it seems that Buridan’s Ass might be confusing preferences or decision-making an ass might make (‘choosing’), as opposed to a moral (or deeply rational) decision that he can’t make because animals are not moral agents but instead are meat machines made up of billions of atoms in a state of flux. Is this the same for all species?

Let’s briefly look lower down the scale regarding insects: Researchers are beginning to understand how, without much in the way of individual decision-making power, ants can make complex decisions, according to a recent article in Mind Matters (March 30). It’s best understood, they say, as something like an optimization algorithm: Scientists found that ants and other natural systems use optimization algorithms similar to those used by engineered systems, including the Internet.

In his book, Miracle of the Cell (2020), biochemist Michael Denton talks about the ways our bodies’ individual cells appear, to researchers, to show intelligence: “No one who has observed a leucocyte (a white blood cell) purposefully—one might even say single-mindedly—chasing after a bacterium in a blood smear would disagree.” Did it decide to chase?

Although this sounds quite eerie, just like other non-human creatures or cells, it’s unlikely such brainless organisms are conscious like humans but instead are capable of reacting, as well as possessing, like a complex machine, information, like being hard-wired. But notice how all of these things have one thing in common: They’re purpose-driven.

But back to animals: Although I believe they have lower levels of consciousness, despite having no sense of self, it’s highly unlikely that they think rationally. Cameron Buckner, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Houston, argues in an article published in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, that a wide range of animal species exhibit so-called “executive control” when it comes to making decisions, consciously considering their goals and ways to satisfy those goals before acting.

Buckner acknowledges that language is required for some sophisticated forms of metacognition, or thinking about thinking. But bolstered by a review of previously published research, Buckner concludes that a wide variety of animals—elephants, chimpanzees, ravens and lions, among others—engage in rational decision-making. (Jeannie Kever, University Website, Nov 1, 2017)

As for the paradox of the hungry and thirsty ass: Buridan concludes that a rational choice cannot be made in the donkey’s scenario and that, until it can be debunked or clarified, we must suspend judgment. Is he right? Or did he overlook the true definition of the word/concept ‘Identical’? Can two separate things be identical? To degrees, in some ways they can but not in every conceivable way.

In Christian theology, in most ways, God the Father is identical to the Son and Holy Spirit, but uniquely and ultimately, the Three Persons are One. Regarding humans: A finite person, and his or her identity, is twofold and not identical. His or her status is that of, a) the species homo sapiens and, b) the separate individual him/herself, ie their human character(s): Both physical and spiritual beings.

So, if no two things are separate in every single way right down to the micro or geographical level, then Buridan’s Ass does not have identical options of choosing the food or water. The very fact that the food and water spatially occupy two different left/right geographical locations, also reinforces such a notion of ‘difference,’ as opposed to ‘identical.’

There are lots of other examples in everyday life of how things can’t be identical: ‘Identical’ twins are not 100% the same. While environmental factors can, and usually do, alter their appearances, do their DNAs differ? According to assistant professor of genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, Ziyue Gao: “One particularly surprising observation is that in many twin pairs, some mutations are carried by nearly all cells in one twin but completely absent in the other.” (Now, scientific journal article by Tracy Staedter, June 14, 2021.) Then there are so-called ‘identical’ bank notes or coins, but try looking at them under a microscope. The key word in the confusion regarding the paradox of Buridan’s Ass, should be ‘almost.’

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast