by David P. Gontar (September 2016)

ABSTRACT

In her reading of Pericles, Prince of Tyre, Marjorie Garber traces an entertaining trajectory from incest to romance, maturity, and sexual alterity in which the troubling consanguineous detour is closed with finality. (Garber, 754ff) This is accomplished by reliance on the device of a robust chastity. It is argued here, however, that the sweeping aside of incest is deceptive, and that Shakespeare rather is concerned to illustrate its vitality and predominance throughout. Chastity is better perceived as a mask concealing the never-resolved claims of incest. Its avoidance in Pericles is merely aleatory, making the play not so much a romance as a satire in which the meaning and stability of conventional love and matrimony are bracketed. While these conventions are maintained in keeping with Shakespeare’s traditionalism, they should be understood not as primary and inevitable but as bulwarks against the incessant pressures and prerogatives of incest. Chastity is best seen as a confectionary enterprise whose elaboration only underscores the inexpugnable and unruly impulses of human nature. The play’s smiling finale may be likened to the assemblage of figures atop a wedding cake: plastic and generic. The ultimate attitude of the play is therefore one not of “romance” but of comedy.

1. The Affliction of Incest: Antiochus, Inc.

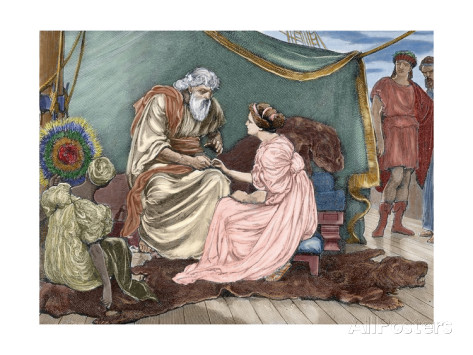

The essentially problematic inception of Pericles must be recognized in order to come to terms with its meaning. Antiochus the Great offers his unnamed adult daughter to the bachelor princes of the world. During this period of competition for her hand Antiochus is having with her an ongoing liaison. In Gower’s prologue it is implied that this forbidden relation is known to the public (“By custom what they did begin was with long use account’ no sin.” 1, 29-30) In spite of this many suitors came to Antioch to vie for her love. It is unclear, however, whether these noble youths knew of the father/daughter affair or not. If Gower’s words be taken seriously, everyone knew about it and chose to turn a blind eye; in that case, why would the suitors venture forth? On the other hand, if the suitors were in ignorance, what shall we make of Gower’s statement that the public has become inured to the King’s indiscretions? It’s hard to imagine that everyone in Antioch knew and approved and somehow managed to hide such important news from those of other cities.

As an additional hurdle, Antiochus imposes a riddle on all who would woo his daughter; failure to resolve this will result in the immediate death of the aspirant. Since the solution is the fact of royal incest, and no one has yet answered it thus, all have been summarily executed, their heads mounted as trophies on the palace walls. This implies the suitors are unaware of the father-daughter intimacy, an inference again inconsistent with Gower’s proposition.

Into the lists now marches Pericles, Prince of Tyre, to whom the conundrum is proponded by an angry monarch.

I am no viper, yet I feed

On mother’s flesh which did me breed.

I sought a husband, in which labour

I found that kindness in a father.

He’s father, son, and husband mild;

I mother, wife, and yet his child.

How this may be and yet in two,

As you will live resolve it you.

(1, 107-114)

At once does Pericles apprehend the meaning. But the question is, Why, if Antiochus is having a clandestine affair with his own child does he advertise that affair by making its recognition the answer to a riddle confronting all the young men who knock at his gates? If his trysts with his daughter are classified information why spread the word, even in cryptic form?

Any suitor in Pericles’ position faces a dilemma: in order to have the daughter of Antiochus and preserve his life he must give the right answer, but if that is done and the awful truth be disclosed, how can he expect to keep his head fixed to his shoulders? The game of the riddle can thus have no conclusion but the contestant’s swift demise. Pericles therefore hesitates, giving no answer but implying he knows the unpleasant facts.

Antiochus in response now changes the rules. He gives Pericles an additional forty days to state the correct answer, saying “If by which time our secret be undone, This mercy shows we’ll joy in such a son.” (1, 159-160) What is the point of waiting? There has been no expounding of the meaning by Pericles and according to the terms he should die posthaste. And since a suitor’s death is mandated in any case, why does Antiochus tarry? The extension of time has no logic.

Sensing his imminent doom, Pericles decides to escape Antioch. When Antiochus learns of his departure, he is outraged, and sends his manservant Thaliart to follow and kill him. Why is Antiochus surprised? He has placed Pericles under the shadow of inevitable death, and given him over a month to warm to the prospect. Why does he not have him executed on the spot? Here is another query with no satisfactory answer.

It seems that Antiochus is of two minds. As passionate about his daughter he wishes to have the world’s acclamations. At the same time he fears censure and rebuke. Thus he wavers between announcing his affair and concealing it.

Pericles’ situation is more complex. Why has he come to Antioch? Many have ventured, but none has returned. That is public knowledge. Antiochus is obviously unmarried at this time. When Pericles sees the Daughter he is set aflame with ardent zeal (“my unspotted fire of love to you” 1, 96). It should be clear that from day one Pericles has been drawn to Antioch because of the lure of incest. After all, according to Gower the fact of Antiochus’ notorious possession of his daughter is well-established. That advance information helps us grasp why Pericles doesn’t take a more accessible lady to be his wife and mother to his children. The reason is self-evident and lies in what distinguishes her. Finding a suitable wife is not a task with Pericles but, with the advent of the Daughter of Antiochus, an obsession. On confirming the truth, he is seemingly shocked, and yet we find him strangely fascinated. Otherwise, how account for the extremity of his efforts and the risk of nearly certain death he embraces?

When he returns to Tyre he is still distraught and fears Antiochus will send assassins to liquidate him. These lingering anxieties are revealing, for they show his preoccupation with the Daughter of Antiochus, her undenied beauty and narcoleptic charms. When Pericles confides his anxieties to Helicanus, he is advised in simple terms to “go travel for a while,” (2,11) with Helicanus to rule in his absence. And so commences the peregrinations of Pericles which constitute the backbone of this play, as he wanders about the Mediterranean world, a Prince without a place to call his own. He is in flight. But as time passes, we see that Prince Pericles is not in flight from the wrath of Antiochus, who with his daughter perishes early on, but from the flames of incest that burn in his heart. He continues to live out vicariously the sin of Antiochus and it is this, as we shall see, that drives him hither and yon unceasingly.

Of this entire problematic Marjorie Garber seems to have no inkling.

At Antioch Pericles encounters King Antiochus and his nameless daughter . . . . Following heroic precedent, Pericles successfully interprets the riddle that has stumped other suitors, only to find to his horror, that the answer is “incest” — an unlawful relation between parent and child. Antiochus treats him with exaggerated courtesy, “glozing,” as he says, once he realizes that Pericles knows the answer to the riddle, and Pericles flees for his life, resigning his kingly duties to the old man Helicanus. Pericles is fleeing the anger of Antiochus, but he is also, by the logic of romance, seeking himself. (Garber, 763)

Garber never considers what brings Pericles to Antioch, or that he might have other feelings about incest besides “horror.” Does Pericles travel all the way from Tyre to Antioch because he is “seeking himself”? It’s hard to even know what that would mean. Suitors arrive from the four corners of the earth to win Antiochus’ daughter, and this presumably cannot be explained by the desire for inheritance and wealth, as they are already noble and affluent. Jane M. Ford writes:

Pericles guesses that the riddle spells an incestuous relationship and his life is immediately endangered. But a more crucial factor is involved, both in Pericles’ guessing of the riddle and in the effect that it has on his subsequent behavior. His intuitive response to the riddle marks him as an early “secret sharer” since the proclivities of Antiochus are his own. (Ford, 43, emphasis added)

Garber asks us to account for Pericles’ interminable Wanderjahr by chalking it up to a “seeking of himself,” without any foundation in the text for such a trite, fairy tale notion, or any way to assign that vague locution a clear meaning applicable to him (and not to his royal predecessors in love). What is it, we may ask, that stands in the way of Pericles’ desired self-possession? What inner problem makes his life more arduous than those myriad other suitors who go in search of a suitable spouse? The stumbling block provided by the text is a carnal contagion caught of Antiochus. Yes, it is a “horror,” but what is really horrible is that Pericles discovers it in his own trembling core. He is transfixed, mesmerized, not only by the daughter of Antiochus, but by her relationship with another man, her father, the King. One is reminded of the adage of Carson McCullers, “They are the we of me.” Shakespeare implies that what is within Pericles at the moment he meets Antiochus and his daughter is a confused mass of desire, jealousy, and prurience. In this his position resembles that of a cuckold. That is, there is a yawning schism within him, as is usual in Shakespearean drama. Pericles is torn between the allure of incest and its revolting aspect, and it is this inner struggle, not any abstract or philosophical “search” for “himself” that drives him to venture forth he knows not where. Fatally, in Garber’s naïve rendering there is no conflict. Jane M. Ford observes: “Ostensibly to flee possible death at the hands of Antiochus, Pericles leaves Tyre and is soon again the third party in another father/daughter/suitor triangle.” (Ford, 44) That repetition tells the story.

2. Any Port in a Storm

Garber at several points in her lecture on Pericles compares him to King Lear (e.g., Garber, 764) overlooking that Lear, too, is hoist by the petar of incestuous desire. (Gontar, 2015, 76ff) Storms in Shakespeare almost always signify inner distress in his protagonists. Lear, Macbeth, Cassius, Clarence, Prospero and Pericles all contend with such meteorological emblems because they so graphically illustrate what is happening in their souls. By contrast, a young and indecisive man merely unsure which direction to take in his career would hardly be appropriately represented by such hyperbolical Sturm und Drang, thunder and lightning. And Pericles experiences not one but two such outbursts of unhappy nature. Notice that the theme of incest is not dropped but re-kindled. After Pericles’ mission of mercy in Tarsus (Sc. 4), Gower takes up the refrain again.

Here have you seen a mighty king

His child, iwis, to incest bring;

A better prince and benign lord

Prove awe-full both in deed and word.

Be quiet then, as men should be,

Till he hath passed necessity.

(5, 1-6)

It is Pericles, “the better prince,” who, in relation to incest, has not yet “passed necessity.” Instead, the first storm at sea arises, and we see how it ravages him. He is shipwrecked.

GOWER

He deeming so put forth to seas,

Where when men been there’s seldom ease,

For now the wind begins to blow;

Thunder above and deeps below

Makes such unquiet that the ship

Should house him safe is wrecked and split,

And he, good prince, having all lost,

By waves from coast to coast is tossed.

All perishen of man, of pelf,

Ne aught escapened but himself,

Till fortune, tired with doing bad,

Threw him ashore to give him glad.

[Enter Pericles wet and half-naked]

And here he comes. What shall be next

Pardon old Gower; this ‘longs the text.

[Thunder and lightning]

The hero exclaims:

PERICLES

Yet cease your ire, you angry stars of heaven!

Wind, rain, and thunder, remember earthly man

Is but a substance that must yield to,

And I, as fits my nature, do obey you.

Alas, the seas hath cast me on the rocks,

Washed me from shore to shore, and left my breath

Nothing to think on but ensuing death.

(5, 27-47)

Poor Pericles, exposed to the fury of the elements as was King Lear, is vomited up by a rude sea on the shore of Pentapolis, where he encounters a group of comical fisherman mending their nets and musing about the vagaries of life.

THIRD FISHERMAN

Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea.

MASTER

Why, as men do a-land – the great ones eat up

the little ones.

(5, 67-70)

Here the idea of cannibalism recapitulates in subtle form the same conceit we saw in the Riddle of Antiochus: “I feed on mother’s flesh,” an unconscious and ribald allusion to the incest theme. Pericles learns that Pentapolis is govered by good King Simonides, who is hosting a joust or tournament whose victor will be eligible to marry Thaisa, the princess of Pentapolis. Why is the identical fact pattern raised again, unless to keep the issue of incestuous conduct alive and center stage? Taking up his father’s armor which also miraculously appears in the surf, he hies him to the court of King Simonides to once again fight for the hand of a princess sought after by many. And in Scene 9, King Simonides, in a strangely familiar outburst of paternal possessiveness, accuses Pericles of using witchcraft in winning his daughter’s favor, making himself a traitor in Pentapolis. (9, 47-50, with allusion to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Othello) He then banishes the young man from his city and threatens to take his life. (9, 90-95). In other words, King Simonides, in response to Prince Pericles’ victory in the joust for his daughter’s espousal, flies into a jealous rage and declares his intention to have the Prince slain, a point-for-point repetition of the behavior of the incestuous King Antiochus. As it turns out, Simonides is dissembling playfully and in fact privately approves the match with Thaisa his daughter (reminding us of Prospero in The Tempest). But isn’t the royal pater here tinged with incest? “Although Simonides has ‘dissembled’ his opposition to the marriage, it also reflects his true ambivalence toward this usurper of his fatherly rights.” (Ford, 44) No matter how jocular or playful, the strife between King Simonides and Pericles over possession of Thaisa keeps the incest motif alive in the bowels of the comedy. Pericles remains in flight from the voracious imago of father-daughter intimacy and twice interrupts the propinquity of King and princess. The difference is that Pericles the incest-tormented suitor at the court of Antiochus is the victim of a real plot against his life, whereas in the second version Simonides is merely putting on a murderous rage as a way of introducing himself to his prospective son-in-law. Pericles’ flight from incest has landed him in once more in its mortal coils.

Yet that flight from incest is not on Garber’s radar, for she apparently has smaller fish to fry: namely, the abstractions “rebirth,” transformation,” and “reconciliation.” “The relationships between the two fathers and daughters . . . are used as foils for the central recognition scene between Pericles and Marina in scene 21.” (Garber, 766) What “transformation” would mean for Prince Pericles in the absence of his unwitting preoccupation with incest is not clear. Nor is it correct to say that the “recognition scene” in Pericles is “central.” It is located at the climax of the play.

Unlike the incident at the court of Antiochus, during which Pericles is prevented from marrying the object of proscribed desire, the King’s daughter, in the sequent episode Thaisa, daughter of King Simonides, does wed him. Unbeknownst to her, the lingering pall of incest hangs over the groom and their match. The double-bind is this: to the extent that Thaisa and her father are bound by wishes of intimacy, her union with Pericles lies under a moral cloud; but to the extent that she is at liberty to be his wife she lacks the piquancy his soul requires. The same inner conflict we beheld in the storm preceding Pericles’ fateful visit to Thaisa’s home of Pentapolis still smolders afterwards. Now married to a figure who is an emotional stand-in for the wanton daughter of Antiochus, Pericles remains in flight from incest, this time permanently attached to the symbolic object of temptation. As his troubled hegira continues, he makes for Tyre, his pregnant bride in tow, and, once again, finds himself engulfed in storm suggestive of his inner turmoil. When Thaisa perishes of a traumatically-induced childbirth and her body must be abandoned to the surging waves, Pericles can only blame the capriciousness of divinity, unable and unwilling to perceive the possibility that the “powers-that-be” disapprove of his incestuous longings and impulsive acting out.

O you gods!

Why do you make us love your goodly gifts,

And snatch then straight away? We here below

Recall not what we give, and therein may

Use honour with you.

(11, 22-26)

This poignant cry of Pericles in the midst of howling winds is usually taken as a token of Shakespeare’s resolute humanism, chastising the gods and suggesting that their destructive behavior savors of sadism, a fault not exhibited by us glorious mortals. The deeper and pervading irony is harder to discern, though the word “snatch” is a vivid clue. [from the Middle English, snacchen, i.e., the vulva; see American Heritage Dictionary, 5th ed., p. 1657; see also, Titus Andronicus, II, i, 95] Where the benighted protagonist can only protest the injustice of heaven, Shakespeare’s readers can see his self-deception and bad faith, refusing to acknowledge the forbidden impulses keeping him in thrall. This deeper humanism is missed by those who fail to apprehend the burden of wanton desire under which Pericles languishes.

Despite the grim scene at sea, all survive. Thaisa’s waterproof coffin is salvaged by the physician-savant Cerimon, who brings her magically back to life, whereupon she takes refuge in the Temple of Diana, goddess of chastity. The infant, Marina, is deposited by Pericles in the city of Tarsus with Cleon and Dionyza, whom Pericles befriended in Scene 4. There she grows into a remarkable and preternaturally graceful young lady who recalls nothing of her parents but their royal names. For fourteen years her father remains aloof, mourning with “unscissored hair” (13, 29) the loss of Thaisa, not once returning to Tarsus. Such gaps in generations are significant in Shakespeare, for they drain parent/child relations of filial knowledge, so that when parent and child of the opposite sex finally meet, the emotional safeguards preventing romantic attraction are missing (as they are in Greene’s novel Pandosto which formed the foundation for The Winter’s Tale and Leontes’ meeting with his daughter Perdita). By the time Pericles finally does wend his way back to Tarsus, Marina has been abducted by pirates and is gone. Cleon and Dionyza tell him she has died, sending the bestricken King into a whirlwind of remorse and disabling melancholy, “never to wash his face nor cut his hairs. He puts on sack-cloth, and to sea,” says Gower, our faithful chorus. “He bears a tempest which his mortal vessel tears, and yet he rides it out.” (18, 28-31) Believing his child dead, he commits himself to the sea and “Lady Fortune.” (18, 42)

3. Chastity in the Bordello

There follows the hilarious vignette of the brothel in Mytilene, which is where the pirate kidnappers have sold Marina. The standing joke is that having paid a fortune for this alluring lass, Pandar and Bawd discover to their dismay that their new recruit is as resolutely chaste as Diana herself, whom she cites as her celestial guardian:

MARINA

If fires be hot, knives sharp, or waters deep

Untied I still my virgin knot will keep.

Diana aid my purpose.

(16, 142-144)

Not only does she refuse to prostitute herself, Marina goes so far as to preach continence to the patrons of the brothel. (Sc. 19) What is not often noticed, however, is that Marina’s rejection of those men is a recapitulation of the Daughter of Antiochus’ rejection of her suitors. The Daughter of Antiochus spurns the suitors on account of her affair with her kingly father; Marina, the daughter of an incest-addicted father, makes herself unavailable to her would-be clientele because of a seemingly inexplicable chastity. Daughter of a roving father captivated by consanguinity, it isn’t too much to say that Marina is the fruit of her father’s incestuous yearnings. That same nisus towards incest is thus lodged within herself and is held in check by her assumed chastity, a defensive construct. The proof is readily available. After she liberates herself from the den of bawds and whores, Marina becomes a tutor of the arts in Mytilene and accepts a proposal of marriage from the governor of the town, Lysimachus, a patron of the very brothel which enslaved her, and who there tried as a customer to engage in sex with her. (Sc. 18) Of all the men she might select as a mate, virtuous, honorable and abstemious, Marina chooses an habitual brothel user old enough to be her father. Each time they engage in conjugal relations she will recall his past life of libidinous commerce and his attempt to buy intimacy with her. Why does she select such a fellow, unless her love of “chastity” be a mere strategem, a mask to protect her from the lure of promiscuity and incest? Was not her mother’s relationship with King Simonides tinged with incest (as we have seen)? Did not her father fall in love with a young woman having a intense affair with her own father, and did that experience not make such an impression on him that he spent the remaining years running from his own incestuous inclinations? Is it, then, surprising that Marina would “yield her virgin patent up” to an older man accustomed to the liberties of regular non-marital sex? The paradox of such chastity as that which Marina cultivates is that it blossoms in the soil of her parents’ lurid appetites, and though it fends off the crowd of brothel regulars, in the end Marina submits to the importunities of the eldest of them.

4. Haven’t We Met Before?

Comes now the “recognition scene.”

GOWER [speaking of Pericles]

We left him on the sea. Waves there him tossed,

Whence, driven tofore the winds, he is arrived

Here where his daughter dwells, and on this coast

Suppose him now at anchor. The city strived

God Neptune’s annual feast to keep, from whence

Lysimachus our Tyrian ship espies,

His banners sable, trimmed with rich expense;

And to him in his barge with fervour hies.

In your supposing once more put to sight;

Of heavy Pericles think this the barque,

Where what is done in action, more if might,

Shall be discovered. Please you sit and hark.

One day our refugee from incest moors himself in Mytilene. To no man has he spoken in three months, nor has he eaten solid food. “He lies upon a couch with a long overgrown beard, diffused hair, undecent nails on his fingers, and attired in sack cloth.” He will speak to none. Yet those in Mytilene suggest that Marina, of all people, his own daughter, wise and skilled in persuasion and the liberal arts, engage him in conversation. Think about this. When in The Winter’s Tale Florizel and Perdita travel to Sicilia and meet the sad and resigned King Leontes, the latter is mightily struck with her, so lovely is she, so mysteriously resembling his deceased wife. In Pandosto, Greene’s novel on which the play is based, the King falls unwittingly and passionately in love with his daughter, and soon thereafter commits suicide. The 16 years of separation have extinguished all familiarity, allowing an immediate love to arise in his breast. Now we have Pericles and Marina coming together quite by chance. Had she still had occupation in the brothel at that moment, and were he well in body and mind, it is implied they would have engaged in intimacies with one another. That is, it is only by Accident, not policy or forbearance, that they avoid sexual relations.

Overjoyed to find his long lost daughter, Pericles recovers. The incestuous fever seems to evaporate. Yet his ecstatic and paradoxical address, “Thou that begett’st him that did thee beget . . . .” (21, 183) points back to his original complex. Most readers will follow Garber in scanting the significance of these words, choosing instead to thrill at Pericles’ recovery and rejuvenation. It continues. The Goddess Diana comes to him in a dream, dea ex machina.

My temple stands in Ephesus. Hie thee thither,

And do upon mine altar sacrifice.

There when my maiden priests are met together,

At large discourse thy fortunes in this wise:

With a full voice before the people all,

Reveal how thou at sea didst lose thy wife.

To mourn thy crosses, with thy daughter’s, call

And give them repetition to the life.

Perform my bidding, or thou liv’st in woe;

Do’t, and rest happy, by my silver bow.

Awake and tell thy dream.

(21, 225-235)

5. Conclusion

And so Pericles makes one more final trip. The sheer perfection of the reunion of all these characters in Ephesus has no equal in literature. Many tears of joy are still shed there. Yet therein lies the crux of the matter. It is the grain of sand that makes the pearl, not the oyster’s perfection. When Marina kneels to Thaisa in Diana’s temple she cries, “My heart leaps to be gone into my mother’s bosom.” (22, 67) That’s a nice sentiment but set in the context of what has transpired in this narrative it may give us pause. For if mother and daughter are one, to embrace the former is to hold the latter. What cause has Diana, after all, to show kindness to Pericles, who has kept the demon of incest aglow in his breast for all these years? Only time will tell if it is vanquished. And how is it that the goddess of “chastity” has played the bawd to all these copulative paragons? Which of them will live in true chastity henceforth? The chastity of Thaisa was born of necessity, having lost her husband and having been abandoned in a strange land. The chastity of Marina was as a moat defensive in a setting of commercial promiscuity, reminding us of the disdain showed by the daughter to Antiochus to foreign youths. Chastity was builded like a wall when it was needed, and, with the blessing of its very patroness, is tossed aside of small worth when perils fade. The prognosis for Prince Pericles and his recovered bride must be guarded. (Gontar, 2013, 26)

It has been argued with some justice that Shakespeare himself is — above all — a votary of Diana. (Gontar, 2013, 161ff) But recalling the cruel fate of Actaeon at the hands of Artemis it is not easy to recognize in this accommodating Dian the stern countenance of heaven. We may conclude thus: even the gods go masked. The only true divinity is the one Ted Hughes identified as the “Goddess of Complete Being.” Diana is the guise of Venus. As Corporal Nym would say, “That’s the humour of it.”

Historical Postscript

In Much Ado About Nothing, Beatrice, in meditating on her distaste for matrimony, says something interesting: “Adam’s sons are my brethren, and truly I hold it a sin to match in my kindred.” (II, i, 57-58) Isn’t that odd? Is Beatrice a theologian? She maintains that as all men are brothers to have intimacy with any of them is to tumble on the bed of incest. The only remedy, therefore, is to remain a virgin. But despite her doctrine of universal incest it is apparent in the play that she is secretly attracted to Benedict – surely one of her brethren — and eventually marries him, committing the very incest she had so recently and openly condemned. That is, her life is a knowing and voluntary passage from chastity to incest.

What is the provenance of this idea of universal incest? Apparently it arose in the period of religious reform which began its fermentation in the early 16th century. Queen Marguerite of Navarre (1492-1549), in her secular writings (Story Thirty of The Heptameron) and her religious poetry (The Glass of the Sinful Soul) expatiated on this theme, bringing it out of the shadows into the light of public understanding. The human condition is essentially one consistent with fallen nature, and in light of our common descent from Adam there are no intimacies amongst us which are free of the taint of incest. These writings passed from Marguerite to her faithful lady-in-waiting Anne Boleyn, the mother of Elizabeth Tudor. After Anne’s death in 1536, young Elizabeth made an impressive English translation of Marguerite’s spiritual treatise in 1544, dedicating it to her learned step-mother Katherine Paar.

A few years later, this precocious student of universal incest had an affair with her uncle/step father, the Lord High Admiral, Thomas Seymour. There is substantial evidence that Elizabeth became pregnant and gave birth to a baby boy which survived. It is apparent that the Lord Protector’s secretary, William Cecil, was called upon to place this royal orphan in an appropriate home. Thus this child of was situated in the manse of John de Vere and raised there for ten years, at which time he was transferred to Cecil House (denominated the “Court of Wards”), where he was given a most exceptional education and developed an interest in literature, theater and writing.

At the age of 20 he made his entrance into the Court of Elizabeth, much to the Queen’s delight, becoming her favorite. Because of the lapse of years during which they had no dealings with one another, Elizabeth’s perceptions of this dashing young man were not those of a mother for her son but rather of a woman for a handsome and alluring courtier. We find the same sequence of events in The Winter’s Tale (after long separation Leontes is attracted to his biological daughter Perdita) and in Pericles (after long separation, Prince Pericles apprehends his daughter Marina not as his child but as an especially attractive young lady whom, under different circumstances, he might have courted).

One can see in this highly condensed chronology that these works of “Shakespeare” tell the story of the author’s life at court. They bear no connection to William of Stratford. Thus we account for the observation of Beatrice that “Adam’s sons are my brethren, and truly I hold it a sin to match in my kindred.” Elizabeth suffered from the same complex as Pericles and Marina: she longed for chastity and represented herself to the English people and posterity as the “Virgin Queen.” Yet she had many affairs. She was herself (1) the product of incest, (2) a close student of incest and (3) an incestuous partner with her son, Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. It is hoped this postscript sets all pertinent facts in context. It is, of course, always possible to disagree, so long as we find better ways to account for the data so as to reach a more cogent and comprehensive explanation.

WORKS CITED:

Jane M. Ford, Patriarchy and Incest from Shakespeare to Joyce, University Press of Florida, 1998.

Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All, Anchor Books, 2004.

David P. Gontar, Hamlet Made Simple and Other Essays, New English Review Press, 2013.

David P. Gontar, Unreading Shakespeare, New English Review Press, 2015.

Marguerite de Navarre, The Heptameron, Penguin Books, 1984.

Marc Shell, Elizabeth’s Glass, University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

William Shakespeare The Complete Works, Second ed., S. Wells and G. Taylor, eds., Clarendon Press, 2005.

ADDITIONAL WORK OF INTEREST:

Otto Rank, Das Inzest-Motiv in Dichtung und Sage, translated by Gregory C. Richter as The Incest Theme in Literature and Legend, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

_________________________

David P. Gontar’s latest book is Unreading Shakespeare. He is also the author of Hamlet Made Simple and Other Essays, New English Review Press, 2013.

To comment on this essay, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish thought provoking essays such as this one, please click here.

If you have enjoyed this essay by David P. Gontar and would like to read more of his work, please click here.