Most contemporary atheists bemoan human suffering and have great faith in the State, scientists and medics solving our problems. They regard the conflicts on earth and human pain as the best argument against the existence of God. It certainly is an emotionally powerful argument but it is not the most intellectually formidable one, especially for many sophisticated theologians or philosophers.

As a lapsed atheist already committed to God, I try hard to avoid suffering and try to live a morally good life, despite my many failings as a miserable sinner. However, I hope I can recognize the important message of God and pass it on.

But as a good argument for God’s existence, I believe the Creator’s complex relationship with time and eternity is without doubt the most puzzling, profound reasons for doubting one’s faith on an intellectual level. However, I’ll leave that for another book—if I ever get the time to write it!

To return to ‘where is God during suffering?’, the simple answer is God is with us all the time, as long as we are prepared to follow the way of the Cross. And without occasional suffering, and I’m mainly focusing here on mental pain, we’re prone to forget God and become lost in sinful earthly pleasures that are short-lived, anti-climactic and ultimately meaningless.

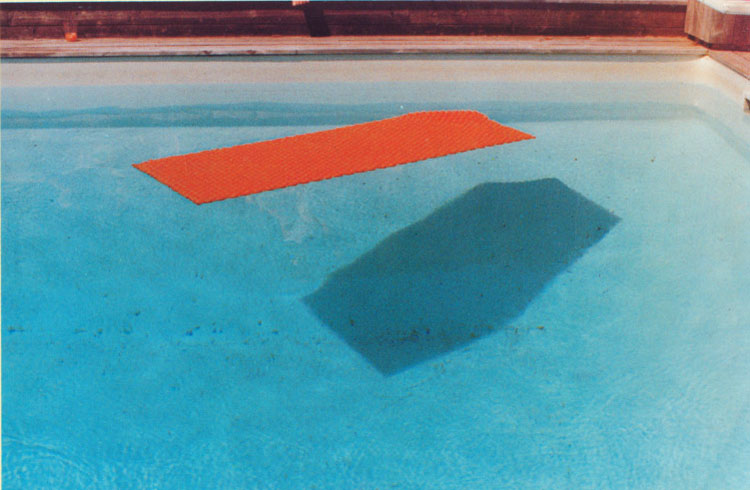

A good example of this can be seen in the 1968 semi-surreal film, The Swimmer, which I believe can be viewed as a good analogy of the typical stages of life in a human’s existence. Originally written as a short story by John Cheever in 1964, the film masterpiece starred Burt Lancaster as Ned Merrill. A middle-aged man whose biological age is that of a slender young athlete, Ned decides to swim his way home through his neighbors’ swimming pools in the suburbs of Swinging Sixties Connecticut.

Lancaster, like a modern-day Elmer Gantry in swimming trunks, was perfect for the role of Ned, having starred eight years previously, with a similar narcissistic persona, in the aforementioned Hollywood movie about a phony preacher.

He appears to be a vain charmer, filled with glib optimism and focused exclusively on this world and its transient pleasures. He is unintellectual, self-centered, and a lady’s man with a big ego. He views attractive women as carnal opiates to ease his tensions and he is unfaithful to his wife and seeks popularity and pleasure in every aspect of his life (the male menopause on steroids).

There’s not an ascetic bone in his body. He’s a morally handicapped sexual predator who is always flashing his pearly white teeth and ostensibly in a good mood. It’s fictitious characters like Ned who today give laudable masculine virility a bad name.

One assumes he’s one of those people who takes the psychobabble reckless advice of ‘be yourself’ and ‘follow your dreams.’ Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot, Stalin and Jack the Ripper also followed their dreams and strived to be their authentic selves. That’s not to say the polar opposite of following the herd and ‘fitting in’ is much better. There’s got to be a happy medium.

Ned might not be an evil tyrant like the above despots, but he nonetheless has a spark of the psychopath. As he ‘swims’ home on a sunny day, he encounters his many upper-middle-class neighbors. These WASPs are all clones of one another and their idle chat sounds identical.

They’re mostly preoccupied with gossip and suburban concerns, while nursing hangovers from the night before. Their summer recreational lives consist of drinking and socializing with friends by the swimming pools of their luxury homes. There’s nothing wrong with this in moderation, but when they idolize their own wills above God, they become separated from their Maker.

Such a materialistic situation is infused with symbolism and metaphor. The theme of the book/movie is probably a humanistic view of failure and the delusion of the American Dream, but I view it through a theistic lens. The story can also be seen as life’s journey of the innocence of childhood and youth, gradually changing all the time, reaching the terror of existence in adulthood with all its hardships and existential trappings.

Theistically, it’s a wake-up call that we can’t make it alone: We need God, but only after we have been convinced through the reasonable faith of thorough investigation on His existence; or through the revelation of a spiritual experience not based on delusions, blind faith or fear of death.

Delusions of the flesh are no stranger to Ned. As he starts out on his journey home on a bright Sunday, the neighbors he meets along the way are initially friendly. However, geographically closer to his destination, they gradually become hostile while the weather turns inclement, foreshadowing an ominous outcome to Ned’s little eccentric adventure.

When he reaches his destiny, Ned finds his house boarded-up and somewhat dilapidated. This is where the story turns eerie and takes a surreal twist, where time and space are both vague and confusing, echoing Ned’s mental turmoil.

Thunder in the distance forewarns the coming of a storm. It looks like an exhausted Ned has inherited the whirlwind. He bangs on the once pearly gates of his house which have turned rusty, and he hears the nostalgic ghostly sound of joyous laughter on the unkept tennis court as the rain falls down on this half-naked shivering creature drenched in scenes of pathetic fallacy and failure. Narcissists like Ned with giant egos always overplay their actions and eventually self-destruct. The graveyards of the world are jam-packed with them.

But Ned isn’t physically dead yet, despite ostensibly looking like he’s afflicted with a kind of dementia. He wonders is it so late that his family have all gone to bed? He tries to open the garage doors to see what cars are parked inside but the doors are locked. Going toward the house, he notices it, too, is locked. He shouts, pounds on the door, and tries to force it with his shoulder, and then, looking in at the windows, he sees that the place is empty.

Drowning in his sorrows and alone in his darkened intellect, one wonders: What is he thinking? God? Or is he so lost in this world of material sin that he remains unreflective and drifts off aimlessly and continues swimming in the stream of delusional consciousness seeking more earthly delights? Or, perhaps this bleak situation is a gift from God to preserve Ned’s salvation by way of pain, thus prompting him to see the Light?

John Cheever said: “It seems to me that man’s inclination toward light, toward brightness, is very nearly botanical—and I mean spiritual light. One not only needs it, one struggles for it. It seems to me almost that one’s total experience is the drive toward light. Or, in the case of the successful degenerate, the drive into an ultimate darkness, which presumably will result in light.” (New York Times Book Review, March 6, 1977).

The obsession of being happy and experiencing constant pleasure have effectively separated the once successful degenerate Ned from God. Think about it: When our lives are fully focused exclusively on the pursuit of transient pleasures, we forget about God.

The suburban Lotus-eaters in The Swimmer seem to have everything: Beautiful wives; wealthy husbands; healthy children; the luxury house, the dog, the swimming pool and white picket fence; big cars, jewelry, fine wines and Champagne, superficial friends, and much more.

They’re so busy competing in one-upmanship and bodily pleasures that they’ve forgotten God and unwittingly embrace Satan’s way: the god of this world of cheap thrills and false idols. It’s only when they’re drowning in the sea of mental pain will they have any chance of acknowledging the Cross and reaching out to God to be saved.

Nobel Prize-winning Russian novelist, the late Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, could tell you a thing or two about the power of the Cross. In extreme contrast to such effluent decadence of the swimming-pool set in Ned Merrill’s world, when Solzhenitsyn was imprisoned in a Siberian gulag in the freezing cold, he became so exhausted one day that he dropped his shovel, slumped onto a bench and waited for a guard to beat him to death. This is what happened to other prisoners when they fell down in the camp.

However, a frail fellow prisoner approached Solzhenitsyn and scratched the sign of the Cross in the mud, then he quickly walked away. As Solzhenitsyn stared at those two lines scratched in the clay, the message of the Cross began to relieve his despair and give him strength. Through the power of the Cross, anything was possible; so, he picked up his shovel and slowly went back to work and lived to tell his story in some of the most dramatically profound volumes of non-fiction in world history (The Gulag Archipelago).

Golgotha is a reminder to all of us that the bad thing about the ‘good life’ is by endeavouring to maximise worldly pleasure, we might never find God while living a life of affluence sipping cocktails at our proverbial swimming pools and solely focused on our next pleasurable fix. It’s at times like this when our souls are disordered and our intellects darkened.

But we are more likely to find God when we fall face down at the narrow gate of our own private gulag. It’s only then, at the end of our rope, away from the broad road leading to kidney-shaped swimming pools and cocktail parties, that our suffering will subside and become more bearable in a fallen world of relative cosmic seconds. “Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it (Matthew 7:13).”

Before reverting back to belief in God, intellectual pride had almost eaten my mind and soul. So, my advice to any reader who is an unbeliever but has an open mind and open heart: Before beginning your first steps on the Road to Damascus, be on guard, aware of gas-lighting and question the official Establishment narratives, which are usually propaganda and hostile to Christianity. Christians are obliged to test everything to see if it is true or not and hold fast only to what is good and morally right.

More: Avoid the bad theology of Modernism, be humble and consider the following Bible verse if ever pain or sorrow should enter your life: “When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you. When you walk through the fire, you will not be burned; the flames will not set you ablaze (Isaiah 43:2).”

I believe these words above, despite not believing in a Saviour to ease their suffering, will resonate more with pessimistic atheists, who are far more intellectually astute as opposed to those of a glib, optimistic bent with a deep faith in future utopias provided by a super-nanny State.

For the pessimist, in life there are more pricks than kicks. They seem to view the world in infrared instead of through the rose-tinted specs of the New Atheist. And pessimistic atheists are aware that we live in the wreckage of contemporary Western civilization, thus, there is less emphasis on political ideology or Pollyanna wishful thinking but more of a sense of the great loss of something transcendent, something spiritually higher to fill the God hole deep inside our souls, yearning for meaning. They sigh the word’s made famous from a Peggy Lee song and quoted quite fittingly in Charles Taylor’s fine book, A Secular Age, when she wearily asks after a life of sadness and broken dreams: “Is that all there is?”

For the believer, it’s not. There’s more to life, and suffering is what’s to be expected in a fallen world. And although such a world is broken, there’s more to it than particles vibrating or atoms bumping into one another in and around the swimming pools of la-la Lotus-land.

All the so-called ‘good’ things of the material world will never fully satisfy us, as we’ll always end up frustrated, angry and seeking more pleasure. Only in union with the Logos, can God elevate us to our highest level of spiritual wellbeing and, before we depart this life after genuine repentance and accepting God as our Saviour, if redeemed, an eternal afterlife of bliss through the Beatific Vison awaits us. When the ‘Neds’ of this world immerse from their pools soaked in failure and spiritually wounded, remember: ‘I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleanness, and from all your idols I will cleanse you.’ (Ezekiel 36:25)

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link