The Divine Maria Callas

by Phyllis Chesler (December 2018)

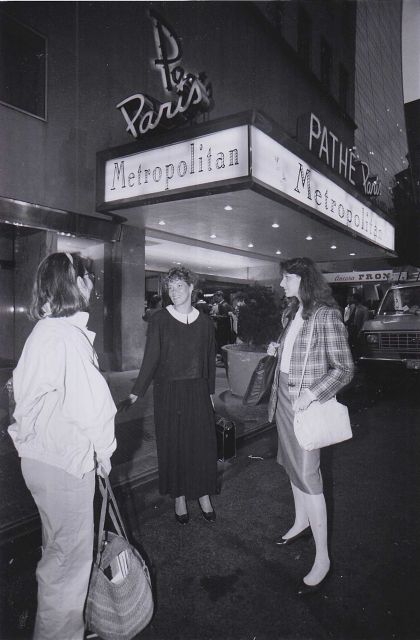

The Paris Theater, now celebrating its 70th year and long known as a single screen “art house,” is located on West 58th St. near Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, right across the street from the Plaza Hotel. Back in the day, one could see a film, then cross the street to have coffee or high tea at the Palm Court and be serenaded by a violinist and a pianist.

I have happily been going to the Paris since the late 1950s when it was known for its foreign films aka serious cinema. Here, (and uptown, at the Thalia), is where I first saw Bergman, Fellini, Almodovar, Zeffirelli, Merchant and Ivory, the incomparable Deepa Mehta, and every movie that starred Joan Plowright and Maggie Smith. I was among the first on line for the New Year’s Day showing of Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet.

I have happily been going to the Paris since the late 1950s when it was known for its foreign films aka serious cinema. Here, (and uptown, at the Thalia), is where I first saw Bergman, Fellini, Almodovar, Zeffirelli, Merchant and Ivory, the incomparable Deepa Mehta, and every movie that starred Joan Plowright and Maggie Smith. I was among the first on line for the New Year’s Day showing of Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet.

Once, the crowd was younger, film buffs all. Now, the Paris seems to draw cultured senior citizens—a dying yet magnificent breed. And so, many a gray head recently turned out (I among them) for the current offering: Maria by Callas, Tom Volf’s documentary about one of the greatest opera stars to ever command a stage; Callas was known as “La Divina.”

Volf has assembled footage of performances, concerts, interviews, paparazzi, fans, and of her private life. Callas was a musical genius, a great artiste, but in her day she was as famous, as branded, as the non-musical Kim Kardashian is today. She may have been the first opera star to become internationally known. This documentary is a redemptive corrective to the pathography by playwright Terrence McNally which presents Callas as pathetic, a failed woman, unable to persuade the love of her life to marry her, alone and without children.

Read More in New English Review:

In Risu Veritas: Ten of the Funniest Movies and Three Just as Funny Foreign Ones

No False Gods Before Me: A Review of Rodney Stark’s Work

What Makes a Poem?

While this may even be true—she may have yearned for a more ordinary and happier life, and in Volf’s documentary she actually says so—but Callas’s ordinary life is of no interest to any serious opera goer. She is an immortal (think Brunhilde, think Emilia Marty of Janacek’s Makropulous Affair). We care about her because of her consummate artistry, not because she is a woman who may privately suffer the usual demons and dashed hopes that afflict mere mortals and that is so well depicted in opera.

I have always loved opera, despite the fact that, until recently, the great opera composers were all men; the settings too often aristocratic, exaggerated. Most divas suffer awful endings. They go mad (Lucia, Marguerite, Lady Macbeth), die of consumption (Violetta, Mimi), are buried alive (Aida), suffocated (Desdemona), burned (Norma, Azucena), or simply expire inexplicably (Isolde, Abigail). Others are stabbed (Carmen), knife themselves to death (La Gioconda, Butterfly), take poison (Leonora, Juliet), or leap to their death (Tosca, suspended forever in our imagination—an earlier, solo version of Thelma and Louise). ‘Tis true: their male counterparts often suffer similarly tragic fates.

That’s what makes it opera.

Am I romanticizing an art form that re-enacts patriarchal triumph and the “undoing of woman,” as Catharine Clement suggests in her book Opera, or the Undoing of Woman? Is opera dangerous because it both glorifies and de-sensitizes us to women’s daily destruction? Are opera’s women “only” severed, singing heads, witnesses to historical oppression, unable to escape it onstage—at least, not until we have done so in real life?

But where else, except on the operatic stage, can I see the dusky, the colonized, the outlawed, the pagan priestess (Aida, Carmen, Violetta, Norma), in Clement’s words, “sing their resistance”? Where else but at the opera can I see powerful, emotionally vital, sexual-spiritual women commanding such respect, or members of the ruling classes, in full evening dress, weeping for a sexually independent gypsy (Carmen), or for a wife who kills her bridegroom to protest an arranged marriage (Lucia)? Perhaps the tragic endings are precisely what allow the divas to play untamed female heroes.

Where else but in the world of opera do we “allow” women, despite an increasing number of exceptions, to be physically large?

At the beginning of her career, the legendary Maria Callas weighed over 200 pounds. For years, some critics scorned her as “the prima donna with an elephant’s legs.” In early photos, she is lusciously fleshy, moist, large. Her weight is what renders her most human, ordinary; unlike her utterly disciplined voice and acting technique, this is an excess which she cannot contain. Then, in one year, Callas loses at least 60 pounds, then more until, at 117 pounds, she becomes almost half her original size. Now she resembles the Duchess of Windsor, Audrey Hepburn, Jackie Kennedy Onassis: severely elegant women who move, not as priestesses on the operatic stage, but as status symbols or screen idols, clinging to the arms of monied men.

At the beginning of her career, the legendary Maria Callas weighed over 200 pounds. For years, some critics scorned her as “the prima donna with an elephant’s legs.” In early photos, she is lusciously fleshy, moist, large. Her weight is what renders her most human, ordinary; unlike her utterly disciplined voice and acting technique, this is an excess which she cannot contain. Then, in one year, Callas loses at least 60 pounds, then more until, at 117 pounds, she becomes almost half her original size. Now she resembles the Duchess of Windsor, Audrey Hepburn, Jackie Kennedy Onassis: severely elegant women who move, not as priestesses on the operatic stage, but as status symbols or screen idols, clinging to the arms of monied men.

Contrary to the popular pathographies (biographies that diminish their subjects by psychiatrically demonizing them), Callas did not diet for mortal love, but for immortal Art. Opera critic John Ardoin quotes Callas as saying: “I was getting so heavy that my vocalizing was heavy . . . I was tired of playing the part of a beautiful young woman and I was too heavy to move around . . . I studied all my life to put things right musically. Why don’t I diet and make myself presentable?”

But Callas remained “too large” in other ways. Her “light” soprano voice dared all vocal registers and roles: the spinto, lyric, dramatic, coloratura and mezzo-soprano. Ardoin is right: It’s as if Callas has “not three but three hundred voices in one.” Callas sang Verdi and Wagner, Puccini, Donizzeti and Bellini, Mozart and Bizet—and nearly everyone else.

But Callas remained “too large” in other ways. Her “light” soprano voice dared all vocal registers and roles: the spinto, lyric, dramatic, coloratura and mezzo-soprano. Ardoin is right: It’s as if Callas has “not three but three hundred voices in one.” Callas sang Verdi and Wagner, Puccini, Donizzeti and Bellini, Mozart and Bizet—and nearly everyone else.

Callas does not have a “good” voice. Unlike the Montserrat Caballe, Renata Tebaldi, or Joan Sutherland, Callas’ voice is not serene or beautifully tame. Musicologist Attila Csampai writes that Callas’ art “is an incessant declaration of war against the aesthetics of the perfectly balanced register, against the impersonal, flawless, soullessly beautiful tone that can be examined like an immaculate female figure.” If you have ever listened to her, you know that Callas’ voice is, alternately, breathlessly young, ravaged, tender, nasal, shrill—but perfection itself when it comes to beseeching the sky gods to take pity on earth’s children. Callas’ voice is Michaelangelo’s Pieta or his Sistine Chapel paintings made song: celestial, serene or passionately mid-earthly. The timbre is a lamenting lullaby or, as conductor Nicola Rescigno puts it, “like Casals playing the cello.”

Callas subjugated voice to character. She threw herself into each role, developed it as if she were a Method Actor. “It is not enough to have a beautiful voice,” she said. “When you interpret a role, you have to have a thousand colors to portray happiness, joy, sorrow, fear . . . Even if you sing harshly sometimes, as I have frequently done, it is a necessity of expression.”

In the beginning, Callas took every part she was offered; indeed, she sang roles (Turandot, Isolde, Norma) that many sopranos refuse because they demand enormous preparation, stamina, and vocal range. “They damage and devastate the voice,” says opera critic Ethan Mordden. Some critics believe that her theatrical perfectionism, coupled with so many different but equally taxing kinds of roles, may have led to Callas’ early, tragic loss of voice. Contrary to myth, Callas was physically frail; performing—on her terms—literally made her sick. Fame only upped the ante. Of her debut at Covent Garden, Callas said: “I had been preceded in London by sensational publicity, and I was terrified by the idea of being unable to live up to expectations. It’s always like that, for us artists: We labor for years to make ourselves known, and when fame finally follows our steps everywhere, we are condemned always to be worthy of it, to outdo ourselves so as not to disappoint the public, which expects wonders of its idols.”

I have never idolized anyone, including Callas. I am not haunted by Callas the woman, but by Callas the artist, who, at her best, is merged in our collective memory with many of the roles she sang. Callas is Norma, the Druid priestess (a role she revived, and sang on stage 89 times); Tosca—devoted to a life of song; the murderous Medea, Lucia, Tosca; the dying Mimi and Violetta. The “real” Callas is all of these—who aren’t real at all. Or are they?

They are real: Opera fans never forget them, and return to them, season after season, from one century to the next. This is the power that art has over both life and death.

For a year, I wanted to write a biography of Maria Callas. Her soul, art, life, times, all called to me. I listened to her recordings and interviews, watched her on film, read her own brief Memoir, read the critics, the pathographies, her family’s memoirs. I came to realize that Callas’ artistic life can only be understood as an opera. Nothing less will do.

Act One: Maria is the younger of two sisters. She believes she is unlovable; she is also a child prodigy. Maria begins studying opera at the age of seven. She drops out of school after the eighth grade and, driven both by her talent and by an ambitious, devouring mother, devotes herself to studying music, full-time. Callas: “I [had] unlimited faith in the divine protection that would not fail me.” Maria sings in Athens when she is 15. In 1947, at 24, she sings in Verona where, both friendless and impoverished, she meets her husband-to-be, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who sees her as the vulnerable genius that she is. Battista is 28 years her senior—but he is a man who has money, and who wishes nothing more than to nurture his wife’s career. Battista puts himself second, his wife’s career first. It takes Maria about 15 years to “suddenly” conquer the opera world. In her words: It is a “tiger” she rides, one she can “never dismount.”

Act One: Maria is the younger of two sisters. She believes she is unlovable; she is also a child prodigy. Maria begins studying opera at the age of seven. She drops out of school after the eighth grade and, driven both by her talent and by an ambitious, devouring mother, devotes herself to studying music, full-time. Callas: “I [had] unlimited faith in the divine protection that would not fail me.” Maria sings in Athens when she is 15. In 1947, at 24, she sings in Verona where, both friendless and impoverished, she meets her husband-to-be, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who sees her as the vulnerable genius that she is. Battista is 28 years her senior—but he is a man who has money, and who wishes nothing more than to nurture his wife’s career. Battista puts himself second, his wife’s career first. It takes Maria about 15 years to “suddenly” conquer the opera world. In her words: It is a “tiger” she rides, one she can “never dismount.”

Act Two: The world treats Callas with a jinxing and fatal combination of voyeurism, adoration, terror, hatred, envy, and devotion. She is constantly photographed, but also hooted at, drowned out, demonstrated against, sued. Like Turandot (the chaste Chinese opera-princess), Callas has never loved or lusted after anything but artistic perfection. Like Brunnhilde, daughter of Wotan, in Wagner’s Die Walkure, the divine Callas is fated to experience mortality: She leaves her nurturing, powerful father (Battista), her own swarthy, fleshy self, her Art—for mortal love, in this case, love for a patriarchal hero, Aristotle (“Aristo”) Onassis. Like Norma, Callas gives herself to Pollione/the Conquering Culture. Like Brunnhilde, she is now a fallen daughter, destined for ordinary life.

Act Three: Once Callas decides to become mortal, she is no longer in her familiar, divinely protected element. She begins to lose her voice—her power. She stops performing. Her genius can no longer protect her from the indignities of ordinary life, or from the “shame” of being demoted from the status of demi-goddess. The fact that her lover demeans her singing, won’t marry her; in fact, publicly humiliates her when he marries another, less musically talented woman, Jackie Kennedy, may be important, but is also beside the point. The diva cannot “succeed” as an ordinary woman. At 50, Callas refuses to become the Artistic Director of the Metropolitan, stars in Pasolini’s film of Medea, sings concerts for a while, but then retreats from the world. She dies in Paris, alone, amidst her mementos.

She is 53 years old.

Curtain.

.jpg) In my view, her tragedy was not only being humiliated by Onassis’s unexpected marriage to Jackie Kennedy (which Callas learns about from newspaper headlines).

In my view, her tragedy was not only being humiliated by Onassis’s unexpected marriage to Jackie Kennedy (which Callas learns about from newspaper headlines).

Callas’s tragedy was that she had been losing her voice. Was her too rapid weight loss to blame? Or, was the fact that she sang every possible role—an impossible and dangerous feat to attempt—partly responsible for the fraying of her sound? Was she suffering from a disease as some thought, one that weakened her muscles and made it increasingly difficult for her to support her “sound”? Was it her medication for this and/or for insomnia and possibly depression that may have caused her fatal heart attack? And, metaphorically, was her heart really broken—even though she continued her relationship with Onassis both during and after his marriage to Jackie?

Was it Onassis’s death, the loss of her best “friend,” that dealt her the final blow?

I have no definitive answer. Volf’s film suggests that Callas was torn between what she calls her “destiny” and her desire for a 1950’s style of womanly happiness and fulfillment: at home, with a husband and children.

May she Rest In Peace. Perhaps she has regained her voice and is performing for the Lord even as I write . . .

__________________________

Phyllis Chesler, Ph.D, is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies. She is the author of seventeen books, including the 20th century landmark feminist classics Women and Madness (1972); Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody (1986); and Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M (1988). Her 21st century work includes The New Anti-Semitism (2003), The Death of Feminism (2005) and An American Bride in Kabul (2013), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and, in 2016, Living History: On the Front Lines for Israel and the Jews 2003-2015. Her work has been translated into many European languages and into Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Hebrew. Since the Intifada of 2000, Dr. Chesler has focused on anti-Semitism and the demonization of Israel; the psychology of terrorism; the nature of propaganda and the importance of the cognitive war against fact and reason; honor-based violence and the rights of women, dissidents, and gays in the Islamic world. Dr. Chesler has published four studies about honor killings, and penned a position paper on why the West should ban the burqa; these studies have all appeared in Middle East Quarterly. She has submitted affidavits on behalf of Muslim and ex-Muslim women who are seeking asylum or citizenship based on their credible belief that their families will honor kill them. Her articles are available at her website: www.phyllis-chesler.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast