by Dan Bornstein (May 2021)

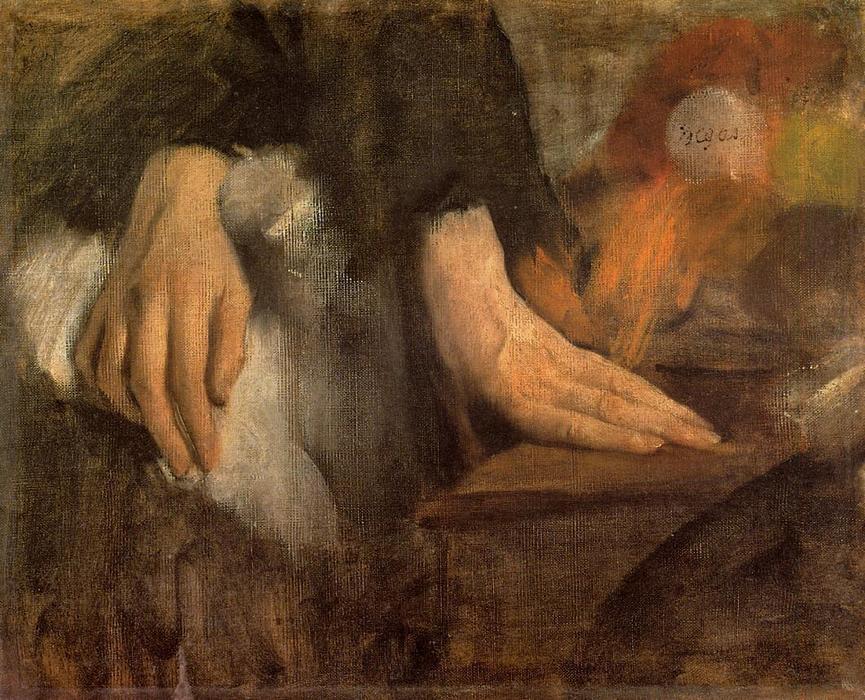

Study of Hands, Edgar Degas, 1860

When I woke up the medical team introduced me to my new right hand.

“Say hi,” ordered one doctor, and this unfamiliar member of my body—originally someone’s left hand, but now an awkward graft attached to my right shoulder—twisted backward and waved to me.

The doctor looked into my eyes: “Now your turn. Say hi.” This time my other, native hand on the left sprang up and waved. And the two hands started clapping together over my head, by themselves, as if I did not exist there at all.

“What am I supposed to do without my dominant hand?” I asked the surgeon.

“Dominant?” he snapped, “It was a mindless parasite. And it almost made you one too.”

He proceeded to remind me of the hand’s past misdeeds: How its muscles had grown thick with twitching rage. How it liked to turn random objects into makeshift swords. How it kept making obscene gestures long after my mouth had been fully pacified.

“But now everything is fine,” smiled a young intern. “You’re lucky we caught it when we did. Your test results are all within the normal range, and there’s no chance the issue will ever recur.”

It took me a few days to learn how to use the new hand—or rather, how to stop resisting it. My hands were now twins, lost in a celebration of sameness, and only I still stood in the way of their blazing worship of each other. Only after many struggles did I manage to recede far enough into the background for the doctors to sign the discharge paperwork.

I was good enough for them now, but my own feeling was another matter: I still could not quite let go. And my restlessness took me to the Repentance Galleries.

Roars of laughter echoed in the halls as visitors moved from one exhibit to another, pointing and ridiculing the stupidity of our ancestors. But the noise gradually died out during the long walk down into the deepest, remotest part of the museum—the Shrine of Dismemberment, where only darkness and reverent silence reigned.

I wandered among the faintly-lit showcases until I found the one that contained my old hand. And as soon as I stood in front of it, the hand sensed my presence and spoke to me in sign language.

“You never allowed me to live,” it motioned, “but I do not belong in this mass grave. The moment you leave I will break the glass. And I hope someone tries to stop me. Nothing would please me more than having to fight my way out of here.”

My body froze; I just stood there and waited for something to happen.

The hand made a rude gesture of dismissal and repeated the signs: “When you leave. Only after you leave. You do not deserve to witness my moment of freedom. I will go find myself a real person, if such a thing even exists nowadays. Give up all hope of seeing me again—unless my rightful master takes pity on you one day and commands me to pull you up, most likely against your will, from the cozy gutter you call life.”

__________________________________

Dan Bornstein is an Israeli writer, artist, and translator from Japanese. He regularly posts texts and visual art on his personal website.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link