The Duke and the Butcher

by Theodore Dalrymple (June 2023)

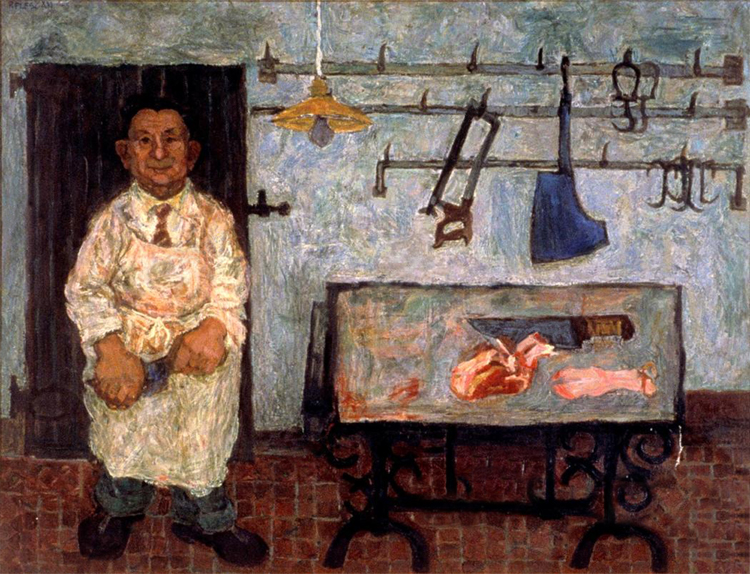

The Butcher (Il macellaio), Pietro Plescan, 1957

The Duke of Cambridge, I think it was, said that he was against all change, even for the better. This seems on the face of it absurd, but I have come to know what he meant, even if I do not myself go quite so far as did he: for the desire for change denotes a state of dissatisfaction. Its opposite, satisfaction, is preferable as a state of mind not only because it is more pleasant in itself but because dissatisfaction breeds a tendency to all kinds of imaginary perfections, which the attempt to put into practice usually ends in hell, or at least hellishness, on earth.

In like fashion, nostalgia generally has had a bad reputation, especially among intellectuals, who regard it both as a refusal to face reality head on and as a dishonest romanticisation of the past; but this seems to me quite wrong. A man who can reach a certain age—I cannot be precise as to what age—without experiencing nostalgia must have had a pretty wretched existence. He cannot recall the irrecoverable past with that mixture of pleasure and sorrow that is nostalgia; he can regret the passing of nothing good.

Such a man is so fixated on the present, or on the future, or on progress, that he has not noticed that deterioration really does take place in the world, or he ascribes to it no importance or significance whatever. In other words, he is still very young or callow—or both—and believes that all change must be for the better. He therefore seeks change for its own sake, irrespective of its actual effects.

Even small changes now disturb me. In my youth, I thought that routine was the worst of fates, the desire of persons without imagination; but now I find routine, at least in some things, reassuring. Perhaps it is the approach of death: routine gives the illusion of changelessness and permanence. By definition, illusion is false of course, above all the illusion of changelessness: but who can live entirely without it?

When I go to the market, therefore, I want the same stalls to be in the same place selling the same things (preferably at the same prices): familiarity breeds friendliness. Recently, however, my butcher in France retired, and I felt almost aggrieved. I had known him a good number of years, and I suppose that my ridiculous sense of grievance—a man, after all, has a right to retire—derived in part from a forced awareness, since he was much younger than I, that I was now old. (You are old when you observe people younger than yourself retire.) And when you see a person in one role in life and one role only, you assume that that role is the whole purpose of his existence, that he has no other. A shopkeeper or waiter who has served you for years who retires or goes to work somewhere else is like a soldier who has deserted his post: he has betrayed you. Let me repeat, lest I be misunderstood: this feeling is entirely absurd.

The butcher was not, in fact, very old, or at any rate what I now think of as very old: a fraction less than sixty. But he told me that he was tired, and indeed he looked almost exhausted. Either he had taken what the French call a coup de vieux (sudden ageing as if by a blow), or I had failed to notice before he told me that he was retiring.

Strangely enough, I had never really considered his life other than as an extremely pleasant and good-humoured man (and very good salesman) behind the counter of his shop, waiting to serve me as if this were the main goal of his life. I had never thought or considered—not for a moment—what his profession and business entailed in the way of effort, but suddenly I did so.

Most of the year he opened at eight in the morning and closed at noon, opening again at four and closing at seven in the evening, six days a week. During busy times of the year, he did not close at lunchtime, but in addition to all this, he made is own charcuterie, roasted chickens to take away and, of course, had to buy all the products that he sold. Since they were perishable, he had to buy them in approximately the quantities in which they would sell. Bad calculations would lead to loss, and then to the need to increase his prices, which would in turn reduce his trade. His situation bore more responsibility, in a way, than that of a banker. At least the banker can take comfort that it is other people’s money that he is losing, and that he will emerge personally unscathed, at least financially, from his bad decisions. Every day, the butcher faced the very real possibility of personal loss.

Many days, his work did not begin when he opened his shop. He had to buy his meat, the wholesale market being at a distance, and he had to make his charcuterie. He had to keep his shop immaculately clean and be nice to his customers, however he felt. When I thought of it, I suddenly became tired myself; and he had been doing it for thirty years, since he first opened his shop! He had earned his retirement.

And then I thought of his initial decision to buy the shop and start his business: what courage it must have taken! No man already possessed of a large capital would have done such a thing. The prospect of failure and consequent indebtedness must have been present in his mind: although, in the event, he prospered and was very successful in a modest way.

What virtues he must have exercised in his career (if you call it a career)! Prudence was essential: he could not afford its opposite. Reliability and fidelity were likewise essential. Mannerliness, honesty and probity were not merely advisable but necessary for the long run, if his business were to have a long run. He had both to attend to detail and have a global view of his business. He had to attend to accounts and earn and keep the trust both of suppliers and customers.

None of this had I considered before he announced his retirement, though it was all perfectly obvious on a moment’s reflection. And what was true of him was true of countless other small businesses that I patronise or rely upon.

Generally speaking, such people as my butcher are described as petit bourgeois. This sociological and economic term is usually instinct with contempt: and I doubt that anyone is flattered to be called, or known as, a petit bourgeois. The connotations of the term are derogatory. When Napoleon said that the English were a nation of shopkeepers (today he would perhaps say that they were a nation of shoplifters), he did not mean it as a compliment. Anything would have been better than that: warriors, mystics, scholars, poets, philosophers, even bankers. Of course, Emperors don’t need to go shopping: everything appears in their households, or palaces, as if by magic, and so their contact with the petit bourgeois is minimal. The latter is not the object of his thought, sympathy or solicitude.

What is it that is alleged against the whole class of shopkeepers and the like—upon whom we are so dependent—that is so damning? In general, it is alleged that it is a class of smallminded and utterly selfish persons who tend to be politically primitive or reactionary, who think that whatever is good for them is good for the country, if not for the world. They are full of disdain for those below then in the social scale and of resentment for those above them. Their ambitions are on a tiny scale and purely egoistic, and their taste tends to be awful. They have no sense of, or feeling for, humanity as a whole. They are uneducated, and their amusements are vulgar and unsophisticated.

The psychological dialectic of contempt and resentment makes the petit bourgeois susceptible to extremist and reactionary, not to say fascist, political movements, especially at times of economic stress. His greatest fear is to sink into the ranks of the proletariat, to have nothing to sell but his bodily labour in a sinking market. On the other hand, he believes that it is the finance-capitalist and monopolist class that has ruined him, so he turns against those who are much richer than himself. The result is that he is inclined to listen to the siren song of populism, if not to something worse. He is fodder for fascists.

Naturally, since all judgment is comparative, the petit bourgeois is compared—unfavourably, of course—with the representative of another class, the proletarian. The exploited proletarian is good and noble because, when he indulges in politics, he is fighting for the poor, and defending the interests of the poor is a far nobler enterprise than defending the interests of those who wish to preserve their own property. Unlike the petit bourgeois, the exploited proletarian is fighting, or struggling, for the benefit of the great majority of mankind: and so his victory, if he has one, is a victory for mankind. Likewise with his defeat, I need hardly add: it is a defeat for mankind.

So noble is the proletarian in comparison with the petit bourgeois, at least in this schematic view of society, that it makes one wonder whether being exploited is not good for the character, in the way that disagreeable sports inflicted upon children and cold showers were once regarded as being good for the character. After all, if hardship results in human improvement, then we should welcome hardship.

It is easier to welcome hardship for others than for oneself, but it is a commonplace of reflection upon life that some degree of hardship is necessary to the development of depth of character. Perhaps it is lucky, therefore, that few people can escape hardship entirely, though the exact dose desirable is not easy to estimate and varies with many factors.

At any rate, it seems to me that the life of the butcher whom I have described was not without hardship, and certainly not without anxiety. What his political views were, I do not know, but I rather doubt that they were of an extreme nature. I do not recognise in him the portrait of the petit bourgeois that is common among intellectuals, who commonly think of themselves as a kind of a natural aristocracy.

My point, however, is this: that we generally go through life without stopping to think of the life of others, who for us have but walk-on parts in the drama of our own lives. This is inevitable to a degree: most of us have dealings with such a large number of others that we can hardly investigate or even imagine the life of everyone whom we meet.

However, the habit of taking things and people for granted, while it is natural, is harmful. With regard to material things, it excludes proper notice, let alone gratitude, for all that exists and contributes to the ease and quality of our lives; it forbears to recall the benefits that we undeservedly receive from the past. With regard to humans, it conduces to indifference and even disdain for many of them with whom we come in contact.

In my experience, at any rate, indifference and disdain infuriate or embitter people more than injustice. Injustice can be righted, indifference and disdain strike deeper. They imply that you are not even worth considering as a human being; at least the unjust man recognises your existence to the point of troubling himself to wrong you.

More and more I am troubled by questions such as where the waiter, the postman, the dustman goes after his work, what are his hopes, his dreams, his fears? It is only then that I begin to appreciate my own good fortune—however much or to whatever degree I might be said to have contributed to it myself. More than ever does it then seem to me important to recognise, even in some small way, the services that other people render me, often with a good grace that I should have difficulty in equalling if I were in their position or with their prospects. Do not ignore, do not disdain.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast