The Father of Heresy

This is Part 1 of the Gnostic Series. Read Parts 2, 3, and 4.

by Jillian Becker (August 2023)

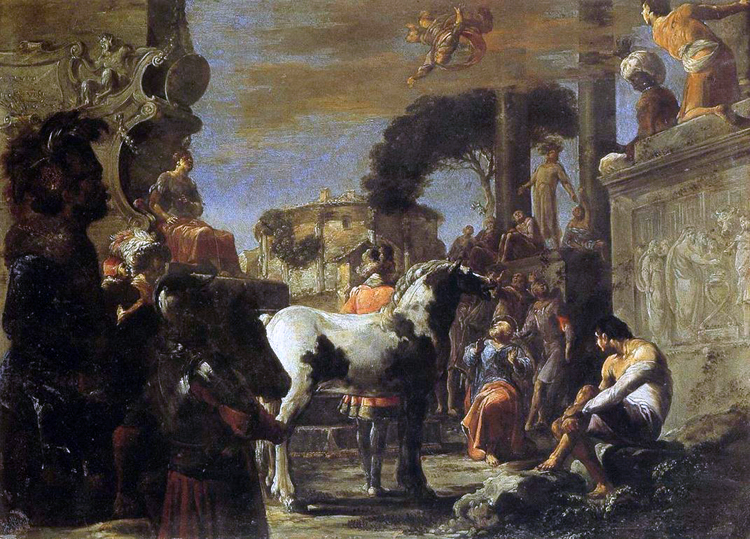

The Fall of Simon Magus, Leonaert Bramer, 1623

In the 1st century C.E., Simon Magus founded a religion that became hugely popular. Even according to the Acts of the Apostles (viii.9 ff.), a document which might be expected to, and does, despise him and his teachings, Simon’s following consisted of the entire population of Samaria, ‘from the least to the greatest.’ Acts further records that he persuaded the Samarians that he, in his person, was ‘the power of God which was great’ —in a word, God; but when Philip, Peter, and John succeeded in converting the same Samarians to Christianity, Simon submitted himself for baptism. According to other sources, he soon, however, reverted to his old claim that he himself was God.

The testimony we have to Simon’s life and teaching is for the most part from Christian sources. Irenaeus, the Church Father, called Simon ‘the father of all heresy.’ But it is not really possible to know to what extent Simon was the originator of the creed he taught. He was certainly eclectic, inspired by a variety of theological fragments wherever he found them. Some of his claims were obviously picked up from the early Christians, others that are Christian-like may have pre-dated Christianity. Elements of truth most probably adhere to some Christian tales of him. If fragments from other sources are granted plausibility, and guesswork applied to all the stories with common sense and regard to known historical fact, a credible account of Simon and his doctrine can be stitched together.

Simon was born in Gitta, Samaria, and came to prominence in the time of St. Paul’s apostolic preaching. He must have left Samaria early in his life or he could hardly have made his fellow-countrymen swallow the story of his celestial origin that he was to bring back with him from abroad. He first became known as a Magus in the large, rich and sophisticated port-city of Alexandria in Egypt, the next most important Greek city after Athens, both being then under the imperial rule of Rome. To make a reputation there was an achievement to be proud of. Whatever Simon did to entertain his public, he must have done it well. A common repertoire of magical performances was attributed to him: the concoction of philtres and potions; the weaving of spells by incantations; the exhorting of idols and images to miraculous result; levitation; opening locked doors from a distance; the inducement of demon-borne dreams.

The self-governing city of Alexandria was named after its founder, Alexander the Great, who was buried there. Under the (Greek) Ptolomies who succeeded Alexander as rulers of Egypt, a museum was established which evolved under their patronage into a kind of university; and a library was built which became the greatest in the ancient world, a proof and continuing cause of Alexandria’s intellectual supremacy. The library remained as a pool and fountain of learning for hundreds of years. However, much of its treasure consisted of pagan and Jewish works that were not to the taste of the Muslims who succeeded in burning it to the ground with all that it contained in or around 640 C.E. It was one of the most deplorable acts of vandalism in history. It is partly because so much was lost in Alexandria that we have huge gaps in our knowledge of the history of ideas, including perhaps the pre-history of the Gnostic cults for which the Church held Simon Magus to blame as the originator of Gnosticism. Originality was—and is—attributed to this or that philosopher because his work survived and so is known to us, but we cannot know everything about his sources, or who his influencers may have been.

It is likely that a portion of wisdom rubbed off on almost everyone who lingered in Alexandria for any length of time. Simon of Gitta apparently acquired some Greek philosophy, perhaps from reading it in the library, or from listening to other people who read it, for he seems to have put it to work when he reinvented himself as a divine incarnation. Platonism and Neopythagoreanism, for instance, are detectable in Simon’s teaching.

His magic art may have been acquired at home before he left it. According to some researchers he did not need to travel abroad to learn it but was trained by indigenous Samarian magicians and mystics.

The established religion of the Samarians—or ‘Samaritans’ as they are called in the New Testament—was a form of Judaism. Their bible was the five books of Moses. They had their own temple at Gezarim (despised by the Jews for whom the only Temple was the one that stood in Jerusalem until it was destroyed in 70 C.E.); and they worshipped in their own way one God, the God of the Jews, Jehovah. At some unknown date, Simon, returning from Egypt, erupted into their midst with his art to entertain them and a strange new doctrine to excite them. They would throng about him to watch his magic performances, and he would preach astonishing things to them.

Jehovah, he proclaimed, was not the supreme God of the universe. He was only a lesser god, though indeed the Creator of this world. But what sort of world was this that he had made? A place of suffering, sin and despair. Now he, Simon, had come down to this earth, appearing as a man, from a realm far above the lowly heaven where Jehovah dwelt. Jehovah was not even aware that anything existed above himself, blindly believing he was the only god, but the truth was that way beyond all imagining, up at an inconceivable height, there was an unknown Primal Father, and He was all good.

Simon warned that he had come to disclose this because the end of the world was near at hand when all would be consumed by fire. The Samarians were doomed unless they followed him, Simon, who alone could save them. The Samarians were impressed. Wanting to be saved, uncountable thousands embraced the new faith he brought them. An inner circle of thirty disciples gathered about him.

He revealed the origin of the universe. He taught that the Godhead was a Trinity. (Whether this Godhead was the same as the unknown Primal Father is unclear.) There was the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. They were not three different persons, but three equal aspects of the same Being. (Two or three centuries later, the Catholic Church held this belief to be a heresy called modalism.)

He, Simon, who had come among them as a man to teach them these things had made himself known as the Father to the Jews, as the Son to the Christians, and as the Holy Spirit to the Gentiles. As the Son, he had seemed to suffer death and affliction. He prophesied that in his present incarnation as an apparent man named Simon, he would again seem to die in his mortal form, but after three days would rise living in the flesh, and be taken up to the highest heaven.

He explained how evil had come into existence from the Primary Source although He Himself was entirely good so that nothing evil could come directly from Him. All things, Simon preached, began with a Thought of the Godhead. This First Thought of God was named Ennoia, a female principle who was the Mother of all creation, for she brought forth the angels who carried out the work. With them, evil began. They were jealous of her powers and their most evil act was to hold her, the Mother, captive in the world they made. For thousands of years she was reincarnated over and over again to suffer the pains of earthly existence. In one of her lives she had been Helen of Troy. Her latest incarnation was as a Phoenician woman whom he introduced to his followers by the name of Helen, because, he explained, that had been her most famous name in the past. He had come to seek her and having found her would now rescue her from the clutches of the demon-angels who held her captive, free her from the cycle of birth and death, and restore her to her rightful place in the highest heaven.

Christian accounts depict Simon as an immoral poseur who tried to buy the secret of miraculous healing from Peter and John. (Hence the ecclesiastical crime of ‘simony.’) They say that Helen, his consort, was a prostitute from Tyre, and the Samarians, to a man and woman, including the most learned and perceptive, had been taken in by a cheap trickster. He presided, they said, over ritual acts of sexual intercourse in holy orgies. St Epiphanius wrote of him that he made use of semen and menstrual blood in his magic.

Simon predicted that he would be ‘execrated’ because what he preached was strange and hard to believe. His doctrines contradicted the conventional beliefs of the classical world, denounced the God and the Law and the morality of the Jews, and constituted a threatening challenge to Christianity. In other words, he urged total revolt. His was not merely a rival faith, it was a protest against all order, all authority, of men and their gods. It was a revolt against the world. He would open the minds of men, wrest their souls from the chains of guilt and set them free. In his antinomianism, in his spiritual aspirations, in his revolutionary fire, in certain of his beliefs, he seems to some historians of religion to resemble St Paul, a notion that appalls others and has elicited scholarly works stressing the differences between the two men and their teachings, some demonstrating so profound a chasm between them as to render such comparison absurd.

It is not known what became of Simon. Some said that he died in or near Rome. Two different stories of his end were rumored, both in mockery. One was that he was giving a performance of one of his magic arts, flying from a tower, when Peter, who was present, prayed that he should drop to the ground, which he did, to his death. In the other he let himself be buried alive for three days, after which, he predicted, he would emerge alive; but when the grave was opened he was found dead.

Mocked and execrated though he was, and a trickster though he was, and bewildering though his theogony was, yet Simon of Gitta must have been an extraordinary man, eloquent and persuasive, whose claim to divinity was not unique in that era. And his doctrine did not die with him. It flowed into a swelling river of Gnosticism. His ideas—original to him or not—were developed by a series of Gnostic teachers, some of them founding sects that lasted for centuries, flourishing side by side with the Catholic Church, until Catholic Christianity became a state religion, first of Rome under the Emperor Theodosius in 380 C.E., and subsequently of many western European states, so gaining the power to suppress heterodox faiths.

Table of Contents

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, City Journal (US); The Wall Street Journal (Europe); Encounter, The Times, The Times Literary Supplement, The Telegraph Magazine, The Salisbury Review, Standpoint(UK). She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren. Her website is www.theatheistconservative.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast