The Fiddler and His Proof: A glance at Karl Marx, poet and prophet

by Jillian Becker (July 2022)

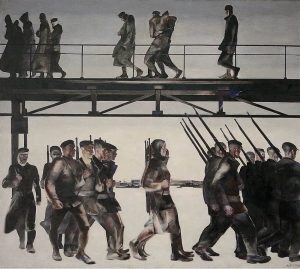

The Defense of Petrograd, Alexander Deyneka, 1928

On May 5, 1818, there was born, in the Prussian city of Trier, one of those rare persons who change the course of history. He did not live to see his prophecies warp the world. He died in 1883, and the first earth-shattering event of which he was an effective cause came thirty-four years after his death: the Russian Communist revolution of 1917.

Karl Marx was the second child and eldest son of a prosperous lawyer. Two years before his birth, his father, Herschel Marx, had taken a step that must have amazed, even outraged, a good many of his Jewish co-religionists in his (overwhelmingly Catholic) home city, which for generations had had its rabbis from the Marx family: he was baptized by the Lutheran church, becoming Heinrich Marx. Protestant Christianity itself did not attract him irresistibly, but he wanted to play a full part as a citizen of (largely Protestant) Prussia. He was a man of reason who admired the products of reason: machines, engines, modernity in general. In 1824, overcoming his wife’s opposition to the move, he had his seven children (an eighth was yet to come) baptized into the recently established Evangelical Church of Prussia, Lutheran and Calvinist.

In his late teens, Karl fell in love with an aristocrat, Jenny von Westphalen, the friend of his older sister, and at about the same time decided to become a great poet. He wrote love poems to Jenny, and hate poems to the world.

The poems are bombastic, full of religio-romantic imagery. Little meaning can be found in them. But they do reveal the character and mentality of their composer. They are emotional, defiant, rebellious, destructive, swaggering, and express above all a hunger for power. [[1]]

Typical is this section of a monologue from a verse drama titled Oulanem, the eponymous hero speaking:

Ha, I must twine me on the wheel of flame,

And in Eternity’s ring I’ll dance my frenzy!

If aught besides that frenzy could devour,

I’d leap therein, though I must smash a world

That towered high between myself and it!

It would be shattered by my long-drawn curse,

And I would ding my arms around cruel Being,

Embracing me,’twould silent pass away.

Then silent would I sink into the void.

Wholly to sink, not be–oh, this were Life,

But swept along high on Eternity’s current

To roar out threnodies for the Creator,

Scorn on the brow! Can Sun burn it away?

Bound in compulsion’s sway, curse in defiance!

Let the envenomed eye flash forth destruction-

Does it hurl off the ponderous worlds that bind?

Bound in eternal fear, splintered and void,

Bound to the very marble block of Being,

Bound, bound forever, and forever bound!

The worlds, they see it and go rolling on

And howl the burial song of their own death.

And we, we Apes of a cold God, still cherish

With frenzied pain upon our loving breast

The viper so voluptuously warm,

That it as Universal Form rears up

And from its place on high grins down on us!

And in our ear, till loathing’s all consumed,

The weary wave roars onward, ever onward!

Now quick, the die is cast, and all is ready;

Destroy what only poetry’s lie contrived,

A curse shall finish what a curse conceived.

The young poet cast off the Christian God he had been lightly brought up to believe in, but he clung to the concept of Satan and the powers of evil. Here is a lyric of his titled The Fiddler:

The Fiddler saws the strings,

His light brown hair he tosses and flings.

—-He carries a sabre at his side,

—-He wears a pleated habit wide.

“Fiddler, why that frantic sound?

Why do you gaze so wildly round?

—-Why leaps your blood, like the surging sea?

—-What drives your bow so desperately?”

“Why do I fiddle? Or the wild waves roar?

That they might pound the rocky shore,

—-That eye be blinded, that bosom swell,

—-That Soul’s cry carry down to Hell.”

“Fiddler, with scorn you rend your heart.

A radiant God lent you your art,

—-To dazzle with waves of melody,

—-To soar to the star-dance in the sky.”

“How so! I plunge, plunge wihout fail

My blood-black sabre into your soul.

—-That art God neither wants nor wists,

—-It leaps to the brain from Hell’s black mists.

“Till heart’s bewitched, till senses reel:

With Satan I have struck my deal.

—-He chalks the signs, beats time for me,

—-I play the death march fast and free.

“I must play dark, I must play light,

Till bowstrings break my heart outright.”

The Fiddler saws the strings,

His light brown hair he tosses and flings.

—-He carries a sabre at his side,

—-He wears a pleated habit wide.

With lines such as these young Karl expected to be recognized as a towering genius who would be listened to by a dumbstruck Europe. He intended through the power of his words to have an effect on history—a dire and destructive effect, apparently, while waves rolled onwards and pounded rocky shores. But his poems were received less favorably than he had confidently anticipated. The editors of periodicals to whom Karl sent a selection for publication returned them without comment. Indeed it seems that only Jenny von Westphalen was moved by them, especially by those dedicated to her:

Jenny! Do I dare avow

—-That in love we have exchanged our Souls,

That as one they throb and glow,

—-And that through their waves one current rolls?

His father would have liked Karl to take up some useful and lucrative career, in engineering perhaps, or science; something that would have involved him in the amazing developments of the age. Reason was pouring out inventions for the improvement of everyday life: gaslight on the streets, steam powered trains and ships, factories with machines that mass-produced goods. But such mundane things were of no interest to the young man of passionate poetic vision. He would never even visit a factory. Heinrich Marx and his son Karl stood on opposite sides of the post-Enlightenment divide between Reason, which fertilized civilization, and Romanticism, which poisoned it.

Next best to science and technology, Heinrich Marx considered, was law. And so, by the wish of his father—who was to pay ruinously for it in anxiety and money—Karl became a law student at the University of Bonn. He departed from it after one year, under a cloud (an affair involving a duel) and moved to the University of Berlin. He became interested in philosophy. He joined the Young Hegelians—a loose association of professors and students who met and argued in coffee-houses—and worked to achieve a doctorate but failed. He finally got the coveted degree from the University of Jena, which, to raise revenue, offered Ph.Ds by correspondence. Karl had only to send the fee along with an essay (he sent one in which he praised Prometheus for defying all the gods), and his doctorate came to him by post.

His character did not change as he grew older, only his medium of expression. And what a very unpleasant character it was: scornful, petty, spiteful, malicious, hypocritical, covetous, boastful, dishonest, grudging and intensely envious, wildly ambitious, arrogant and overbearing. He scorned peasants—they were barbarous “troglodytes.” He despised “the masses,” “the rabble.” Against his fellow European refugees who like him fled to London after the uprisings of 1848 to evade the crackdown of governments on the politically discontented (coffee-house democrats and socialists as well as downright insurrectionists), Marx railed and sneered; they were “emigrant scum,” “boors,” “toads.” He considered certain “races” to be inferior: the Poles and Czechs were worthy only to be subjugated by their betters, such as “the Austrian Germans,” or even to pass into oblivion. Above all he yearned, schemed and strove, with burning hatred and contempt, for the utter destruction of the bourgeoisie—even while, as an exile, he longed to live again in the bourgeois style of his childhood, and finally did, to his complacent satisfaction.

“Never,” wrote a witness to Marx’s manner, “have I met a man of such offensive, insupportable arrogance. No opinion which differed essentially from his own was accorded the honor of even a half-way respectful consideration. Everyone who disagreed with him was treated with scarcely veiled contempt. He answered all arguments which displeased him with a biting scorn for the pitiable ignorance of those who advanced them, or with a libelous questioning of their motives. I still remember the cutting, scornful tone with which he uttered—I might almost say ‘spat’—the word ‘bourgeois’; and he denounced as ‘bourgeois’—that is to say as an unmistakable example of the lowest moral and spiritual stagnation—everyone who dared to oppose his opinion.” [[2]]

More to his credit, his love for Jenny also did not change. He married her in 1843, and she bore him seven children. (He was proud to be married to an aristocrat. He made sure her maiden name, von Westphalen, appeared on their visiting cards.) He enjoyed his family life. But he was not at all a good provider. To put it bluntly, he was a shameless parasite. He squandered large sums from his father in his early years, then fell into abysmal poverty. Four of his children died, three as babies and one at the age of nine, primarily because their father could not afford to feed them properly or medicate them when they fell ill—though he managed never to go without his cigars. He took money from the rich and the poor. “Last week,” he wrote in a letter dated September 8, 1852, “I borrowed a few shillings from some workers. For me that was the worst of all, but I had to do it if I was not to starve.”

From his mother, left with barely enough to keep herself and her still dependent children when her husband died, Dr. Marx demanded—and received a large part of—his “share” to which he had no legal entitlement until her death. He went time and again for handouts from his mother’s relations in Holland, the Philips family (who later, in 1891, founded the famous electro-technical company named after them). He made false representations to wealthy donors to induce them to fund the newsletters and periodicals he launched or edited from time to time. But the main source of his income was his close collaborator in his efforts to smash the world: the anti-industrialist industrialist, the anti-capitalist capitalist, the anti-exploitation factory owner, Friedrich Engels. The firm of Erman and Engels manufactured cotton in Manchester, which made Friedrich Engels one of the “Knights of Cotton and Heroes of Iron,” as Marx sarcastically dubbed such successful manufacturers, they being the enemy who must be overthrown by revolution. But Engels was an exception in Marx’s eyes because he agreed with everything Marx said. “Engels is the little Pomeranian, always busy, always yapping,” was the impression he made on an observer of the two of them together. [[3]]

Marx mocked and insulted other men in the socialist movement who were more acclaimed or had a more significant following than he did. He strove to destroy anyone whom he regarded as a rival, with invective, insinuation, defamation, sly maneuvers, and even outright lies. He repaid generosity with vicious slander, as he did (for instance) in the case of the famous and highly esteemed writer, scholar, and socialist leader Ferdinand Lassalle, who was particularly helpful and encouraging to Marx. Marx denounced him, jeered at his actions and scoffed at his opinions. In their private communications he and Engels—who was a fierce anti-Semite—abused Lasalle particularly for being a Jew, and—even more despicable in their eyes—a Jew of “n****r” ancestry. In their private communications they called him such names as “Baron Izzy” and “the Jewish n****r”. They poured vitriol on the tailor communist Wilhelm Weitling for “not writing his books alone.” Athough Engels at one time called him “the founder of German Communism,” he and Marx sneered at him as a “utopian communist,” an “emotional communist,” and systematically destroyed his reputation. It was habitual with Marx and Engels to condemn others for what they themselves did, and what they themselves were.

Of the two, at least at first, Engels was the more fluent writer—and possessed the quicker mind. But Engels needed to follow a leader. “I am meant to play second fiddle,” he said. In their collaborations he readily adapted his ideas to Marx’s, even when the thought started in his own head and was elaborated upon too far and too ponderously by his leader. Taking his cue from an outburst of malice from Marx, he wrote twenty pages lightly ridiculing the rationalist philosopher Bruno Bauer and his short-lived Literary Gazette. Bauer was not a threat to Marx or Engels, but Marx seized upon Engels’s mildly amusing essay and turned it into a three hundred and fifty page demolition job of Bauer and his small paper. The result was a heavy tome, infused with Marx’s venom, published under the title The Holy Family. Engels drafted a manifesto that Marx took over and, with Engels’s collaboration, turned into The Communist Manifesto. It set out Marx’s theory of historical inevitability and predicted the rise of the proletariat. It described with passion how capitalism had replaced feudalism thus bringing in the bourgeois era, which was already, inevitably by the “iron laws” of economics, coming to its end, soon to be replaced by proletarian communism. It besought the workers to throw off their chains and win the world. It contains famous phrases which, though attributed to Marx, were actually borrowed from others (and slightly altered); notably, “Workers of all countries unite” (from Karl Schapper, another socialist leader and associate of Weitling); and “The workers have nothing to lose but their chains” (from Jean-Paul Marat, the French revolutionary terrorist). Many ideas and slogans famously attributed to Marx had in fact sprung from the brains of other men. He blithely appropriated them without acknowledgment. More examples: “Dictatorship of the proletariat” (Blanqui); “Scientific socialism” (Proudhon); “Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains” (Rousseau); “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” (Saint-Simon).

Engels came to think and express himself so much like Marx, that scholars have found it hard to determine which of them, Marx or Engels, wrote which passages in The Communist Manifesto, or in later writings that were published under Marx’s name alone. Of the many articles that appeared under his name in The New York Daily Tribune, some are known to have been actually written by Engels, and Engels might have been the author of many more of them.

So great was Engels’s devotion to Marx, he let himself be persuaded to claim the paternity of Marx’s illegitimate child, Frederick. Marx begat him upon the subjugated body (one could fairly enough say slave body since she went unpaid) of his servant Helene “Lenchen” Demuth. He had the baby boy taken away from her to be fostered and forbade any meeting between them until he was grown up. (The name Demuth is pronounced Demut, which means humility. There is a temptation to allegorize when writing about this circumstance: that Karl Marx, the arrogant boastful bully who has an unearned reputation for being a great humanitarian, kept a poor handmaiden and sex-slave whom he shamelessly exploited, and whose name was Humility.)

Engels gave money to Marx; as much as he could whenever he could, but they were not large amounts until 1868, when Engels sold his share in Erman to his partner for so handsome a sum that he was able to keep himself in luxury and Marx in comfort. From that time to the end of his life, Marx was respectably housed in nice bourgeois Hampstead and natural contentment. Still, he was not carefree. He was afflicted with suppurating boils. And his failure to destroy the world and raise a new one in his own authoritarian image hung a pall of gloom over him and his family. So it was that though Jenny and Karl Marx loved each other, and though they had no more money troubles in their last years, happiness was not their lot. Jenny died in December 188I. Karl Marx outlived her by some thirteen months. He died in March 1883, a deeply disappointed man.

And yet … Mirabile dictu, Karl Marx did succeed in doing what he had yearned to do throughout his life: he commanded the attention of Europe—more, of the whole world. He did change the course of history through the power of his words—not in the form of poetry but political-economic theory. His prophecy and his “proofs” captured the imagination of twentieth-century romantics—the vision itself being romantic, though he emphatically denied it. He professed to despise romanticism. Yet romantic he was to a high degree, predicting that after the revolution, human beings would not only be organized in a different kind of society, they would actually be different themselves. In his promised land beyond the sunset of the oppressive bourgeois order and the red dawn of the benign proletarian dictatorship, no one would be exploited by anyone else; all would have whatever material goods they needed, and ample leisure to enjoy the finer things of life; every man and woman would work for the common good and willingly contribute whatever he and she could, no more and no less. It was inevitable. Inevitably it would be the end of the selfishness of human nature. Come the revolution, human beings would become worthy of the fair distribution of goods. Furthermore, in Marx’s revolution, not only would the downtrodden be raised, they would also have the gratification of seeing those who had trodden them down being brought smartly under the boot.

He offered no proof that the “inevitable” communist phase of history would be a happy one, nor even an explanatory description of how it would work. But he knew by the “iron laws of economics” that the capitalist order would “burst asunder”, and there would be violent revolution—for although the end of the bourgeois era was inevitable, nevertheless its destruction must be brought about by force.

He insisted that his proofs were “scientific” (thus paying tribute to reason even as he defied it). But in truth his utopian vision came out of his ferociously rebellious hatred of the civilized world, his contempt for almost everyone who dwelt in it. The revolution had to happen, with blood and tears and massive ruination, because nothing less would satisfy his hatred. Marxism bears forever the stamp of its inventor. It has proved itself a creed of hatred, venomous spite, aggression, scorn, cruelty and intolerance, directed especially at its most devoted adherents by its ruthless tyrants.

In 1844 Marx had boasted to Engels that he would give the world his proofs in a book. His admirers—chiefly Engels—could hardly bear to wait for it. If anyone could prove the inevitability of communism and the need for revolution, Dr. Marx could. They waited eagerly … and they waited. Dr. Marx took money in advance for the book from an interested publisher. Years passed and it was not even begun. Still the faithful awaited the great book of proofs.

Eventually, in 1867, twenty-three years after it was first proposed, it was done. There it was at last, a large book called Das Kapital. At enormous length it explained why an inevitable development had to be forced to happen.

Only it did not explain it. That failure—to reconcile the irreconcilable—really was inevitable.

The large book’s appearance did not immediately create the sensation Marx and Engels expected, though it was rapturously received by Engels himself and a few others. The author “sank into the void” (to repeat a phrase of his own), first of obscurity and then of death.

Decades passed. Then “Marxism” became the name of a new dogma, a sweet dream. It wasn’t the large “scientific” book that did it. What posthumously won the idolization of Marx by multitudes was the mystic vision he had touched on of the new human nature operating in smooth harmony; of hypothetical people all being perfectly equal members of one guiltless working class; of their giving what they could and getting what they needed in blissful contentment; of an end to the struggle for survival as all things necessary to each life came to it by an objective process called “the administration of things”.

Eager intellectuals read the writings of Marx—and found much to dispute over. Soon there were many Marxisms; bitter disagreements, anathematizing, raging battles over interpretations of doctrine, bloodshed and assassinations. “Marxist” revolutions erupted, and “Marxist” regimes were imposed—some for days or weeks or months, and some for decades. Vast territories fell under Communism. After the Second World War, Communist Russia brought all of East Europe under its control. Terrorist “Marxist” armies arose on every inhabited continent. The world was changed for the worse.

The Marxist regimes can be counted among history’s most oppressive tyrannies. They ruled by terror, reduced the people to misery, and caused the agonizing deaths of scores of millions by starvation, torture, slave labor, and executions. And still, now, in the twenty-first century, after the experiment of “Marxism” failed abysmally in Russia and the lands it oppressed, countless idealists continue to be enthralled by it. The universities of the Western world, especially in America, favor it. Latin American priests and teachers plead for it. Terrorist groups kill for it.

Karl Marx is deemed a towering genius. And indeed he “smashed a world”; his “envenomed eye flashed forth destruction”; he “played the death march fast and free,” and millions of his followers, generation after generation, dance to his fiddle, to a death in life, to hell on earth.

____________

[1] The translations are by Clemens Dutt.

[2] Carl Schurz (1829-1906), who observed Marx at a conference in the Rhineland. Schurz later emigrated to America where he became: a lawyer; a newspaper owner and editor; one of President Lincoln’s generals in the Civil War; a Senator; and Secretary of the Interior under President Rutherford Hayes. (See Leopold Schwarzschild, The Red Prussian, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1948, pages 187-188.)

[3] A Lieutenant Techow, who had been a commander of the revolutionary army in Baden in 1848. Like Marx he sought refuge in London and there became involved in the same revolutionary circles. (See Leopold Schwarzschild, op. cit., pages 211-212.)

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal (Europe), Encounter, The Times (UK), The Telegraph Magazine, and Standpoint. She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren. Her website is www.theatheistconservative.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast