by Pedro Blas González (March 2021)

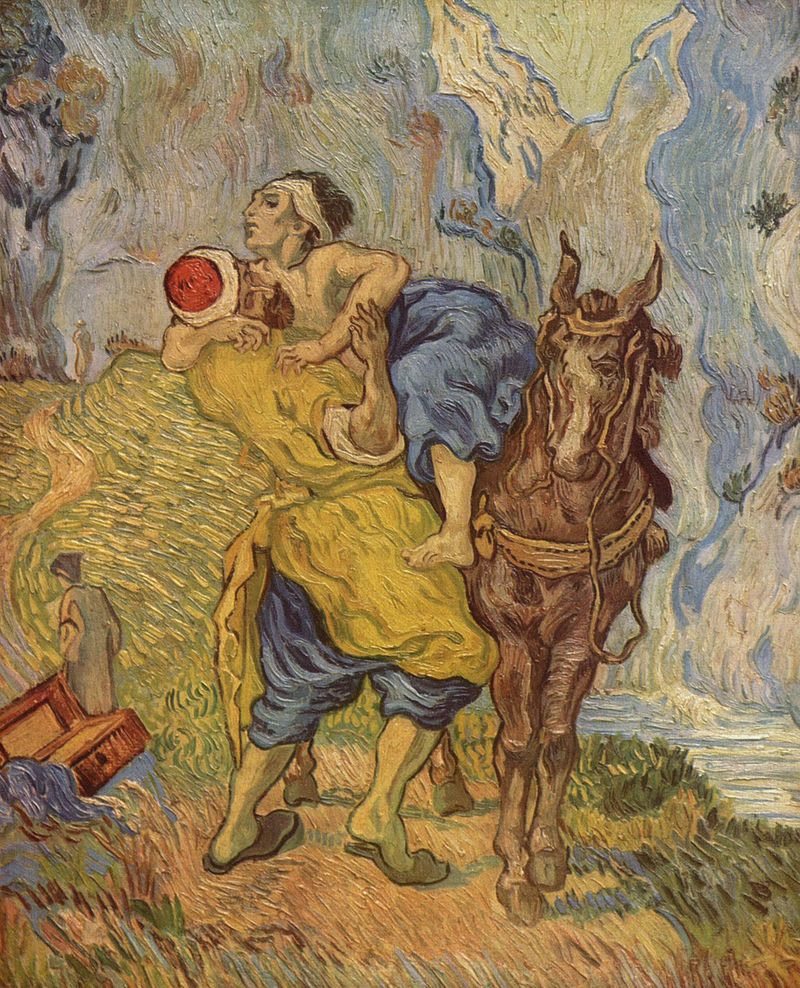

The Good Samaritan (after Delacroix), Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

The experience of life teaches us nothing, if we do not inherit a spiritual tradition to interpret it. —Nicolás Gómez-Dávila, Scholia to an Implicit Text

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly

The Western canon serves as the spring from which thoughtful readers gather the necessary clarity of mind and fortitude to battle the militant aberrations that dominate postmodern intellectual life.

The literary and philosophical works that make up the Western canon form a vibrant tapestry whose theme is sublimity. Another word for this contribution to Western civilization is wisdom.

Besides Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, one of the most emblematic works of the Western canon that makes wisdom its alpha and omega, is Erasmus of Rotterdam’s The Praise of Folly.

While The Consolation of Philosophy has personified Philosophy engage in conversation with Boethius—who awaits execution—The Praise of Folly has Folly lamenting how little respect she gets.

In trying to gain recognition for her essential involvement in all manner of human behavior and affairs, Folly finds herself ignored and betrayed by men. Standing before a crowd of onlookers and wearing a fool’s costume, Folly suggests to those present that they ought to build her a monument to honor her contribution to human affairs, since time immemorial.

Folly articulates the catalog of wretched human character traits, beliefs and behavior. The Praise of Folly is Erasmus’ no-nonsense tribute to the permanent things, those essences that inform man’s nature, which man must continually cultivate in order to avoid calamitous corruption by stupidity.

Never coy, Folly let’s the reader know that she is deeply embedded in the marrow of human nature. Folly’s blatant attack on stupidity leaves no stone unturned. Though, this is only the beginning of her assault on affectation and hypocrisy. While Folly takes aim at imbecility, the havoc it wreaks on human affairs and the platitudes it cherishes, her brightest ire is reserved for hypocrisy.

The Praise of Folly is a work of satire. For Erasmus, satire acts as a mirror that is placed in front of man, while the author dares the reader to ignore the truths it conveys about us.

The Praise of Folly begins with frolicsome Folly sizing up her listeners. In the latter part of the work, Folly unleashes a tempest of chastisement upon man.

Like the vast majority of authors and thinkers that make up the Western canon, Erasmus was a spiritual aristocrat, in addition to being a Christian non-conformist. These qualities make Erasmus a solitary thinker—a precondition for thinkers who seek intellectual honesty.

Folly assures the people who are gathered before her that she is not a counterfeit, “nor do I carry one thing in my looks and another in my breast.” The latter is an affront to shysters of every stripe. Folly is aided by many other human traits. Of central importance to human artificiality, she points out self-love and flattery.

Folly’s critical sword spares no one. Society, she tells us, is populated by fools. Folly then goes on to dissect the dominion that hypocrisy and calumny exert over society.

From self-absorbed intellectuals to unbelieving priests; false friendships, no one is spared. Special attention is paid to those who consider themselves members of the smart-set—the purveyors of crafty wit. What irks Folly most about pseudo intellectuals is their arrogance in pontificating about nature, while remaining ignorant about the nature of human reality.

Folly laments that nature does not propagate wisdom, only foolishness. She informs us that Cicero’s son turned out to be a fool, and wise Socrates’ children “were more like their Mother than their Father, that is to say, fools.”

Life is a tragic-comedy, Erasmus reminds us. Everything is “represented by counterfeit.” Man is an imposter who rarely knows the rhyme and reason of life. For this reason, people “walk up and down in one another’s Disguises, and Act their respective Part…”

So, what does Erasmus tell us is the corrective to this ship of fools? He is adamant that, much like Leibniz’s assertion that “this is the best of all possible worlds,” life as man knows it, is what it ought to be.

Erasmus argues that man should not be disappointed with life, for we have nothing else to compare it to. Man needs to let life be and learn to live with flair and cherish life. For this reason, the role of effective government is not to change the world, as the misguided Karl Marx and his herd of followers would later arrogantly proclaim, but to contain and manage tomfoolery.

The Praise of Folly is a philosophical satire that accepts man and the human condition at face value. Erasmus’ brilliance—this is verified by the longevity of his seminal work—is his understanding of man as a cosmic being.

By removing the fat from social-political interpretations of man and society, Erasmus rests his spirited argument on the abundant evidence of stupidity up to his own time. Given the essence of human nature, Erasmus was confident that man’s future will undoubtedly resemble the past.

A devout Christian, Erasmus’ profound hope was that individual persons could attain immortality in an afterlife. His admonition for the future of man is simple: this too shall pass, only to add to the large repertoire of man’s folly.

Charles Maurras, The Future of the Intelligentsia (L’avenir de l’intelligence, 1905)

In The Future of the Intelligentsia, Charles Maurras (1868-1952), follows the trajectory of men of letters and intellectuals from the Italian Renaissance to the twentieth century.

Maurras argues that what began as reflection by intelligent writers on their independence from the state turned into a degenerate, power-hungry intelligentsia.

The French thinker points out that the quest of men of letters to address and appease a democratic reading public gave way to literature and writing as social-political commodities.

Maurras contends that the popularization of thought through expanded intellectual outlets weakened its ability to decipher truth from reality. Publishing ushered a time of excessive “discussion” without the necessary reflection on matters of fact that should accompany sincere thinking. Maurras writes, “What we will find difficult to discover in a century when everybody writes and discusses, what is not encountered hardly anywhere else, is the enlightened love of letters, and much more the love of philosophy.”

Maurras argues that the fecundity of life, thought and the written word are forms of life that enlighten human existence. These aspects of human life ought to work in the service of life. When successful, the aforementioned contribute vastly to culture and the ability of future generations to understand the past. This means that writing should reflect a manner of existential inquietude, that is, an overflow of vital life that ultimately aims to affirm, not denigrate life.

As a traditionalist, Maurras offers the reader a clean slate to reflect on the nature and essence of human communication. This is why he is critical of the self-possessed literature and writing that intellectuals who politicize human thought produce.

Because the world of letters, Maurras observes, is a “noble exercise, art a fiction in which the mind rejoices freely,” the effect that these endeavors have on culture and customs should remain indirect. In other words, letters must not be politicized and made the explicit vehicle of social-political activism. Politicized letters signal the corruption of writing as a form of human engagement with life and its attendant higher values.

The Future of the Intelligentsia is a warning to Western culture about the perils of intellectuals who embrace mediocrity, through mendacity or cowardice.

Maurras laments the subversive nature that letters began to take in the early twentieth century. He makes the prescient observation in the early part of the twentieth century that “with the means the state has at its disposal, an immense obstruction is created in the scientific, philosophical and literary domain.” He goes on to add, “Our university intends to monopolise literature, philosophy, science.”

Maurras’ perspicuity has proven to be insightful and poignant. Regrettably, the temptation of many intellectuals to subjugate letters to the demands of radical ideology has intensified beyond what Maurras could have imagined possible.

Georges Simenon’s Maigret and The Calame Report

Simenon’s Maigret and The Calame Report is an example par excellence of the roman policier. The novel was first published in France in 1954, and in English translation in 1969.

Simenon was a man busy about town. He walked the streets of Paris, visited its cafés, and is notorious for befriending Parisian women throughout his life. These experiences, he brings to his novels in abundance. Most importantly, Simenon makes use of the daily world of man and women who are busy living their lives as fodder for his literary tales.

Inspector Maigret’s gift for natural psychology is the force that drives Simenon’s Maigret novels. Maigret’s prowess as an inspector is that rare ability that some human beings have for observation that is coupled with heightened perspicuity. What makes the Maigret series of novels unique is not that they solve crimes and apprehend criminals. Most detective novels achieve that, or at least they set out to do so. Instead, Maigret concerns himself with crime as a central trait of human beings, one which, he points out, cannot be eradicated from human nature.

Maigret is a different kind of inspector. The man is a master sleuth of man’s moral compass. This enables him to sniff out people’s motives and behavior; the inner world that makes every person, in a manner of speaking, a micro universe. These qualities set Simenon’s work apart from many other writers.

Simenon’s writing is crisp and clear. His novels are elegant in the manner that plot reflects the tragic-comedy that is human life, and which is exacerbated by postmodern banality.

Simenon is more interested in uncovering the source of criminal behavior than he is about its effect on society. Simenon understood crime to be a staple of human nature that has made its presence felt since time immemorial, and which lamentably will always be with us. Affectation for “criminal reform” is not a staple of Simenon’s novels.

Maigret and the Calame Report is a superbly intelligent and well-crafted novel; one of his best works, where he addresses postmodern man’s demoralized state of moral corruption.

Simenon introduces characters in a meticulous manner that dazzle thoughtful readers with his astuteness and ability to strategize as a novelist. Appearance tramples reality in his novels.

For instance, in describing people who live in an apartment building, Maigret makes profound observations about human nature and the psychology and sociology of criminals. Consider Maigret’s honest appraisal of law-abiding people: “…but it all belonged to the same honest, laborious type of people, the type that is always slightly intimidated by the police.” Ironically, people who respect the police have little reason to fear it, the narrator suggests. This poignant observation tramples the superficial mantra of political correctness that acts as the core of novels and pop culture today.

In Maigret and the Calame Report, Maigret solves the case and apprehends the criminals. Yet he fails to bring them to justice given the vast number of people associated with the case that criminal values and culture have corrupted.

The moral and law-abiding French Minister of Public Works, Auguste Point, who is framed by criminal politicians, is a family man and reluctant politician. Mr. Point is not a Parisian, rather a provincial man who prefers to spend time in the countryside with his family. Maigret sees himself reflected in this defenseless man who is used as the scapegoat of criminals in the government.

Arguably, Georges Simenon stands alone at the pinnacle of the roman policier. Many writers have embraced the genre, but few deliver the kind of sophisticated and insightful works that Simenon offers his readers, especially in lieu of postmodernity. Simenon’s novels are more than just works of detection, rather they are reminders of man’s preference for self-serving values.

The redeeming value of Maigret and the Calame Report is that Maigret fails to solve the problem of good versus evil, especially when the righteous do not have a fighting chance against corruption. For this, Maigret apologizes to Auguste Point, the Cabinet Minister. Both men appear defeated at the end of the novel. But, are they?

________________________

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast