The Inverted Age

by Matthew Wardour (February 2020)

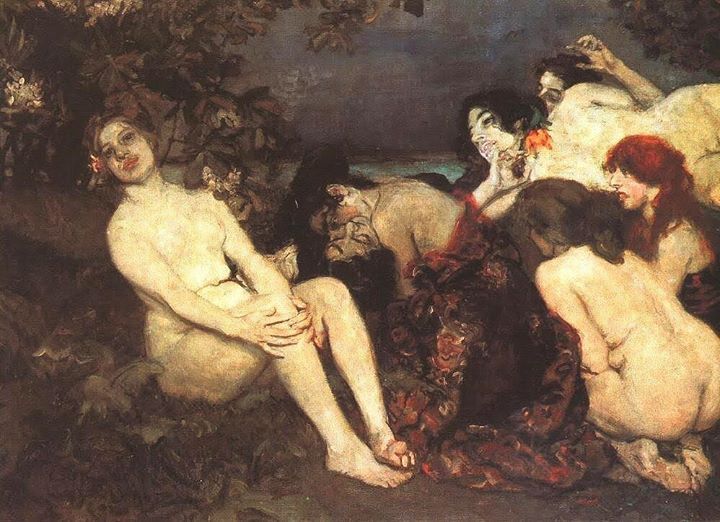

The Vampires, István Csók, 1907

Modern society can be defined by its inversions: inverted snobbery, the elevation of low culture, the inversion of sexual morality, the way we champion notoriety instead of virtue, the way the educated elite now prioritise work over leisure, or wealth over improvement. It does not matter whether you think these are good or bad or neither, but they are an inversion of a previous order, a genuine revolution. The new is better than the old, the inverted better than the original.

Chesterton, in the opening paragraph of Heretics, wrote that it was becoming more fashionable to be heretical, even in 1905:

In former days . . . [t]he man was proud of being orthodox, was proud of being right. If he stood alone in a howling wilderness he was more than a man; he was a church. He was the centre of the universe; it was round him that the stars swung. All the tortures torn out of forgotten hells could not make him admit that he was heretical. But a few modern phrases have made him boast of it. He says, with a conscious laugh, “I suppose I am very heretical,” and looks round for applause. The word “heresy” not only means no longer being wrong; it practically means being clear-headed and courageous.

A twenty-first century variation on this theme is the phrase “‘be different”. There really is no greater virtue in modern life than being “different” (as long as one is the right kind of different). In art this goes hand-in-hand with another of the modern cardinal virtues, being “challenging”. Living near London, I am very fortunate in being able to see many operas. I have therefore witnessed many “challenging” opera productions. I have seen rows of half-naked men and women slapping each others’ bottoms in a debauched production of La Traviata. I have seen a “feminist” production of Lucia di Lammermoor which added to the opera a sex scene followed by a violent blood-drenched miscarriage. Memorably, I once sat through a rather embarrassing production (though the rest of the audience seemed not to mind it) of Henry Purcell’s King Arthur which was re-imagined as a twenty-first century opera about Brexit. The patriotic drinking song— “And heigh for the honour of Old England!” —became an unsubtle parody of Leave voters. The “Cold Genius”, the spirit of winter in the original opera, became a homeless man distressed by Brexit.

Read more in New English Review:

• Libraries That Don’t Respect Books

• The Nihilists’ Masquerade

• The Mob of the Invisible

Though I have seen many wonderful operas—when it works, opera is surely the most magical kind of theatre—I am becoming increasingly reluctant to go because of the folly of so many directors who seem to no longer feel any obligation to be faithful to the composer, librettist and the society in which the opera was written. I feel the same way about most television adaptations of great novels. People justify these televisual abominations by saying that it would be impossible to faithfully adapt the novel for the screen. Well, of course that’s true. But there is a difference between adapting to a medium and adapting to an era. The former is necessary and good, the latter is often disastrous, sacrificing the past on the altar of the present.

I did, however, watch the BBC’s recent three-part adaptation of Bram Stoker 1897 novel Dracula. It was a very twenty-first century version of DraculaA Confederacy of Dunces, I kept coming back to the mini-series out of a rather shameful love of being appalled. Like Ignatius, I had been “pulled by the attractions of some technicolored horrors, filmed abortions that were offenses against any criteria of taste and decency, reels and reels of perversion and blasphemy that stunned my disbelieving eyes, that shocked my virginal mind, and sealed my valve.”

Of course, the trend of adapting classics to modern sensibilities is not a new one. In the eighteenth century, for instance, happy endings were tacked on to some Shakespeare plays. There is surely, however, a difference between an over-correction in favour of moral virtue (which is bad enough) and an indulgence of base instincts, wherein changes are made simply because we, the increasingly barbaric masses, rather enjoy seeing splattered heads, pornography and hearing foul language. All honest people recognise the violent, coarse and prurient temptations within them, but civilized people restrain them (modern man foolishly criticises this as “repression”). Kenneth Clark at the beginning of his great 1969 BBC series Civilisation memorably described the difference between the Viking and Hellenistic imaginations; that is, fear and darkness versus harmony and reason. The Apollo of the Belvedere, Clark says, “surely embodies a higher state of civilisation” than the Viking dragon-like prow. Samuel Johnson was touching upon the same distinction when he wrote that “no greater felicity can genius attain than that of having purified intellectual pleasure, separated mirth from indecency, and wit from licentiousness.” The Victorians—and Dracula is certainly a Victorian novel—understood this better than most.

The recent television adaptation of Dracula, however, was replete with concessions to the twenty-first century. Though I cannot entirely recall the long plot of Bram Stoker’s novel (and I must confess I am in no rush to re-read it), I am quite sure, for instance, that Dracula did not have sex with his lawyer Jonathan Harker and that Professor Van Helsing was not an atheist nun. And I certainly would have remembered Dracula prancing about naked, having emerged from the carcass of a wolf, in front of a group of nuns. Indeed, so many crucial moments were extravagantly gruesome—they never had anywhere near the understatement and restraint necessary to be genuinely frightening.

The series, or at least the first two episodes (we will come on to the bizarre final episode shortly), made no effort to represent the culture and mores of the late nineteenth century. Whereas societies once looked to the past to influence the present and future—Rome looked to Greece, Medievals to Classical civilisation generally—we moderns look to the present and the imagined future to somehow influence the past. We place ourselves in the rather strange and indeed mad position of lecturing the past, which of course cannot hear us, while seemingly ignoring the possibility that the past might have something positive to teach us.

Yet even when watching Dracula’s superficial recreation of late nineteenth century life, one can still see how strong the differences are between 1897 and 2020. How much more beautiful is a neglected old castle than a modern mansion! How much more preferable is the glamour of the ballroom to the grubbiness of the nightclub! These apparently cosmetic changes in fact reveal an entirely different worldview and even morality. This difference is even more obvious in the third episode when Dracula arrives in the twenty-first century (I did say it was ridiculous, didn’t I?). Now everyone walks through the streets as if they really were the undead, heads down in their phones, wallowing in self-importance, stumbling drunkenly through urban squalor. Police wear ridiculous tool-belts and look rather like a mock army, cars roam the streets like demons, skyscrapers and high-rises pierce the heavens. What misery, I thought. But the writers, Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, clearly think these are the best of times. Dracula, taunting a victim in a plain detached house in Whitby, comments on how even ordinary people now live like kings. It is a cliche one hears frequently, and it can quickly be disproved by those real time-travellers in our society, the very elderly, who, often lonely and nursing a sense of cultural loss, are not as convinced that they lived through a time of great social progress. Our kind of pleasure-seeking progress is of little consolation to the old, for whom material concerns are fading, and who need the communal, familial and spiritual obligations from which we have supposedly been liberated.

The strangest thing about the final episode is that, following the first two ludicrous episodes (which, for all their perversity, I somewhat enjoyed as a spectacle), the show suddenly became serious. In the first episode Johnathan Harker, Dracula’s lawyer and eventual victim, is portrayed as a naive Bertie Wooster figure. The second episode features of miscellany of silly characters—most of whom, thank goodness, are killed by Dracula. And in both episodes, despite all the killing, campy jokes punctuate every supposedly-frightening moment. Yet the third episode is centred on the tragic, humourless trollop Lucy, Dracula’s “bride”. And orbiting her is a tedious and pitiful junior doctor whose deep and inexplicable love for Lucy is never meaningfully reciprocated. Throughout the episode one is subjected to pretentious babblings about blood and other psychological pseudo-profundities, culminating in the mundane revelation that Dracula’s weaknesses—his aversion to the sun and the crucifix—are merely in his mind, phobias he has developed over the centuries.

Read more in New English Review:

• Old Books and Contemporary Challenges

• China’s Growing Biotech Threat

• Reflections on Initiation

I was reminded of the Royal Opera House’s recent production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Don Giovanni is not unlike the cinematic depictions of Dracula: a sinisterly charming sexual predator who eventually is defeated. The opera is supposed to end with Don Giovanni being dragged into hell while the strings bow feverishly, the brass and percussion pound against the air, and a chorus of demons taunt the doomed libertine. But instead of that fearsome moment, director Kasper Holten chose to have Don Giovanni standing alone on stage, dragged into a psychological hell of his own making.

Like the end of Dracula, it was a pathetic bit of theatre. It tried to be clever and ended up ridiculous—which is characteristic of much modern art. When will we as a society finally rediscover that being different or challenging is no virtue in and of itself. Like all deliberately perverse fashions—say, the wearing of ripped jeans or the announcement of one’s pronouns in conversation—in the end, albeit after a great deal of damage is done, one only ends up looking ridiculous.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Matthew Wardour is an English musician and occasional writer. He blogs on culture, politics and other things which catch his fancy at smelfungus.blogspot.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast