The Jab to End All Jabs

by David Platzer (July 2021)

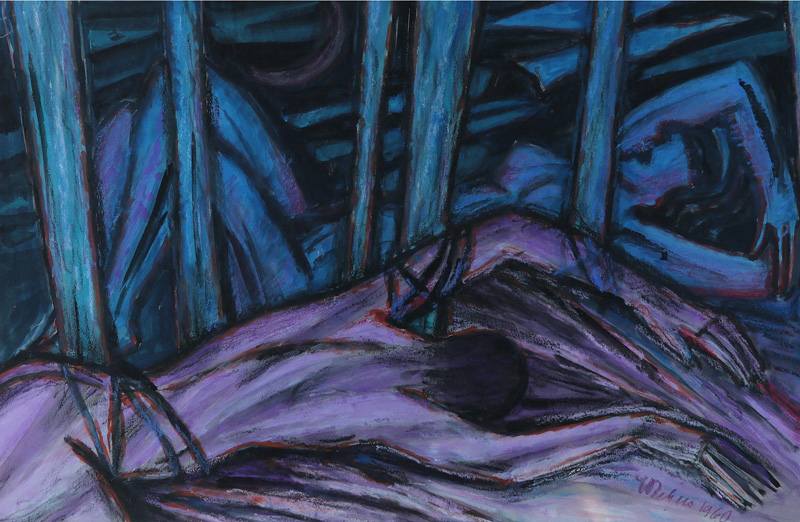

Reclining Couple, Emil Betzler, 1960

The day seemed to have come when the world, or at least the way Alan Marsh had known it, was about to end. Such an event had been announced in crank papers aimed at the barely educated throughout his life and had always turned out to be a false alarm. Long before Alan’s time, it had expected after Christ was crucified and then risen from the dead and yet not come even as Christ’s followers swelled in numbers from a handful to include much of the world.

This last year though, the world had been locked down, to use the term described by it in the English-speaking part of it, in a way that would have been inconceivable until then. Almost simultaneously, the governments of the world decided to order their populations to stay and work at home, it they had the kind of work that could be done in the house, and only go out for essential items, food, medicine and a modicum of exercise. In the more civilized countries just as France, libraries and book shops were allowed to remain open since in France, reading was considered essential—the English-speaking world where few people read anything more than a brief text message on a mobile phone, books were considered of no relevance except for collectors of antiques. Orders of this time could only have been made in an age when almost everyone, even the homeless, had computers and other electronic machines in their personal possession. Plagues in earlier centuries, for more dangerous than this one, could not be contained in this way, not least because of the carriers of the plague of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, were often to be found in personal abodes.

This mysterious virus first discovered in a remote corner of China killed mainly those already afflicted with other ailments—those generally fit and in good health were available to survive it just as they did a common cold. It was very odd in a world that accepted the annual crop of deaths from influenza almost without thinking of it to react this way to this new form of illness. Even odder, the majority of the population accepted this action without too much questioning. Many of those still in employment were happy to be spared their commute which was often far from home and those whose work had to be performed on-site, in shops for example, were provided with some financial compensation even when the shops themselves went out of business. The world had been gradually moving towards a form of socialism and also social distancing especially in the last two decades of ever-increasing automation. People had come to mistrust and fear each other in recent decades as the communities of the past and even family bonds had declined. Social media encouraged people to meet each other on screens and, in consequence, even sex no longer seemed here to stay in the computer age. For the last decades, birth rates had been declining throughout the Western world to a point where it seemed that the most sophisticated elements in Europe and North America now felt that bothering to reproduce themselves was barely worth the effort and was best outsourced, as industry now was, to the still teeming and hungry lands of the Third World.

Alan Marsh felt lost in the world as it had become. Throughout his life, he had possessed an unfortunate way of thinking for himself rather than accepting what he was expected to think. Contrary by nature, he automatically questioned and doubted everything he was told, implicitly or directly, he ought to believe. This natural tendency had only increased as he travelled from one part of the world in search of a place where he could feel at home and at ease. Somehow, he didn’t seem to fit in anywhere. In respect, he had been best in France where, for all country’s bureaucratic apparatus, there was more openness to independent-minded foreigners who loved as Alan did. France’s language, culture and literature. In his first years there, just as elsewhere, there were plenty members of older generations who looked kindly on him and with which he was in tune, despite the difference of age. As these comrades and mentors grew older and died, he was left alone and adrift, stranded with those of his own generation and younger vintages. His contemporaries had always been too green and fresh for his taste and age failed to soften their bumptious immaturity. Alan, though in his youth, not immune to the siren calls of the cinema, television and pop music that bewitched his generation, had put away these childish things as he grew older even if, in moments of aching for his past, these early enthusiasms sometimes returned to him. In his teens, as his contemporaries were following just long-haired Pied-Pipers as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, he turned rather as saving antidotes to such wits as Evelyn Waugh and his son Auberon Waugh, Anthony Powell and the Sitwells who interested him to new interests in art and music just as Phillipe Sollers did in France. He still thought of England as a haven of freedom and eccentricity where any joke went. Even when he lived in France, he had often travelled to England where a few days was too short to tell him that the England he loved was largely extinct and that, if anywhere, it was France who was more inclined to preserve traditions.

He was in England at the time the world went into lockdown. All borders were closed until further notice. Within a few months, many of the train and ferry services as well as hotels were closed and some of them bankrupted.as the closure extended for the few weeks first announced into months. He was suddenly unable to leave or returned to France or anywhere else. Every few days, he received an email from Corrine, a long-time love. He had never been able to separate himself from her and never been able to be together with her because she could not leave her husband, a famous Moroccan-born novelist, Tarquin Garbabas. Garbabas was rarely at home and lived somewhere in a spot unknown to Corrine with another woman. Nevertheless, any suggestion that his wife might have taken up with another man as an alternative to him was a threat to his honour as a man. Corinne lived in fear of his sudden arrivals, swooping down from the hills in a cloud of dust from his motor bicycle, his presence shattering the peace of Saint-Cloud where Corinne lived. On at least two occasions, Corrine had approached a lawyer in the hope of divorcing “him” as she called Garbabas, preferring the pronoun to her husband’s proper name. “We shall talk no more about that,” Garbabas said, tearing the lawyer’s letter into shreds and throwing it into the bin. Further, he told her that he would not only wash his hands not only of her but also of their two children should she persevere with the idea of divorce. Alan tried to convince Corrine that this was no more than a bluff on the husband’s part but she was little inclined to call it. “I must stay his wife until one of us die,” she had told Alan. There was no hope for Alan to find refuge from her. He was doomed to wander even, from one cabin to hotel to another, a twenty-first century Ulysses without an Ithaca. Of havens, let no man speak. Love wilted as quickly as an early spring daffodil.

Daffodil was the name of the company Zed Nero had conceived to produce computer equipment and systems and sell books, films and compact discs. From its humble beginnings in Zed Nero’s garage in his parents’ suburban house on the outskirts of Seattle in the United States’ West Coast, Daffodil had grown into becoming the most powerful, richest company on the world. The heads of nations which in the past had ruled the earth and its seas, now cowered before Zed Nero and discreetly waited for his bidding and the commands emanating from his high, squeaky voice. Daffodil’s headquarters had long since moved from its modest suburban origins to a gigantic underground compound that stretched from Seattle, the capitol of state formerly known as Washington and now renamed Floyd, to Northern California, the heart, it that is the word, of the high technologic empire that ruled the world. Thousands of employees worked there at pitiable wages and with as little dignity as ants. Hardly more to be envied were those who worked at Daffodil plants throughout the world and the company’s department stores which dotted the worlds’ cities, replacing many established emporiums, unable to compete with Daffodil. Zed Nero was a stalwart of the Democrat Party which now ruled the United States and which once had purported to be the champion of workers’ rights. Workers working at Daffodil had no rights other than to resign and face chronic unemployment and the more so since the great virus that had locked down the world and put most independent firms out of business. The Democrat president, Jack Woolsey, a man in his mid-eighties, was merely a figurehead who could rarely emit a coherent sentence and had difficulty in remembering his own name let alone anyone else’s. He seemed to imagine himself to be Franklin Roosevelt and often refer his memories of implementing the New Deal in the 1930s. He was popular in the United States, a country which had a weakness for presidents in their dotage with difficulty in remembering the exact definition of words.

Zed Nero’s first choice for his company after his favourite character in the Bible was Serpent. Zed Nero, thin, entirely bald and with gaping eyes looked like a serpent and felt himself to be one for than a human being. He spoke much the same way his prototype in the Bible had to Adam and Eve in conferences behind doors at Davos and to the impotent members of the United States Congress when they summoned him to answer questions about Daffodil’s complete avoidance of paying taxes or obeying anti-trust legislation. Not that he had much to fear from these hypertrophied politicians. Dressed in his habitual tee-shirt and jeans, Nero smirked at them, many of them on his payroll.

A forgotten girl-friend at the time had advised him to put a name more discreet than Serpent which some might find creepy, and he had chosen Daffodil, a name that he had used in his teenage hippie years. He studied in computer science at university and he conceived and launched Daffodil before his graduation. Only a few years after its creation, Daffodil was a colossus bestriding the world and Zed Nero a billionaire, the globe his oyster. In time, he was able to start working not only altering laws but even what had seemed basic truths since the world began. Others were doing them same thing. In the third decade of the twenty-first century, the leaders of the west, taking their cues from others in the shadows, made marriage, until then considered only possible between males and females, legal between couples belonging to the same sex. About the same time, it became preferable to speak of genders rather than sexes and to insist rather than merely suggest that there not merely two sexes but many. Anyone maintaining the old notions, taken for granted for centuries, was liable to be dismissed and banished from acceptable society.

And now, the virus made Daffodil even stronger. The world and its businesses closed in fear and only Daffodil to buy from! For Zed Nero had been careful to buy up and put under his wing all of the other retailers on the internet. It was all in hand, the new world.

His metal-grey walls had a picture of the Beatles in their flower-power Sgt Peppers days. Harmless as they had seem and without even knowing it, they had spread the seeds that destroy hundreds of years of civilization in a few decades. Of course, that was only the unloosening of the nuts and bolts. Countless workers in the West’s education systems, had been working towards the same goal in universities and working down to schools. The end of the Cold War and of the Soviet tyranny seemed to be the triumph of liberal democracy. It proved the opposite as the success of Political Correctness, the growing obsession with racism in the academy, the entertainment world and the media combined with the new technological giants based in the United States’ West Coast, to dismantle the West’s liberal democracy beyond the dreams of the Soviet Union and working in tangent with Communist China—Zed Nero also had a picture of Chairman Mao on his wall next to the Beatles and George Floyd now the symbol of the New United States in the way George Washington had been the old, the gravedigger of his country over its father. The Great Scam that was the virus was the turning point. It had been surprisingly easy, proving how weak and fragile the world’s civilizations had become, their foundations eaten away in the way a house can be by determined termites.

This new vaccine was the key, as earlier the illegal drugs had been in the 1960s and 1970s. Most people were taking it of their own will, some for fear of an illness that had only real danger to a relatively few, sheep following their unknown shepherds. Others, though less fearful, were none the less taking it for the sake of being about to work, travel, in the hope of meeting friends and family again or perhaps meeting new friends or finding lovers. The vaccine seemed the only way for being allowed to live a full life. Many people did not take into account the possibility that those in authority had found in the lockdown a means of control, a pleasure that they would be loath to relinquish. Everything seemed in order.

Alan Marsh spent much of his time in a cabin near the sea, reading Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, abridged into one volume by D.M. Low, Robert Fagles’s translation of The Odyssey and Proust’s A la recherche de temps perdu in the three volumes published in the elegant Pleiade edition, and hoping during weekdays for a telephone call from Corrine. Her clear voice shining through the ether and gave him hope that life still existed. It was only safe for Corinne to telephone him from the line at her job in Paris. Her own mobile was bugged by her husband. Corinne’s scepticism of the vaccine echoed Alan’s and was supported by her brother, a pharmacist in Lyon. It was curious than in England, while many people who belonged to the “people” as it were, wished to avoid the vaccine, the educated seemed happy to have it pumped into their veins without its contents let alone what its possible long-term effects. The educated were surprisingly trusting of whatever they were told in the press of even the television or radio. They were simple souls which perhaps explained why the books and articles they wrote were so dull in comparison to those of the past.

“I am not having it,” Corrine said to him of the vaccine. “There is no reason for anyone of our age, let alone anyone still younger to have one. Odette {her daughter, aged twenty-one} and her boy-friend, had the virus for a day, perhaps two, and were better.”

Her words reassured Alan as much as those he saw in the internet disheartened him. Meanwhile, he stayed in his cottage near the sea in a remote corner of Cornwall. A hermit’s life had never appealed to him but even provincial towns were becoming noisy, the tattooed people disguised in masks and dressed in sweats and blue jeans too discouraging. Better to be in the woods with the sea a few minutes’ walk away. He surrounded himself with books, enough to insulate the cabin from the winds, often fierce, outside and a cabinet of products made by Weleda and Trumper’s. He might be living like Robinson Crusoe but he had no wish to groom himself in the way of Defoe’s hero. He was not marooned. There was a town only minutes away by foot. He felt stranded and isolated though, he who had been happiest in conversation and in the worldly circles, of charming, amusing people.

One day he was out for a work in the brush when he saw a striking couple. They seemed a latter-day version of Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland in costume as Robin Hood and Maid Marian.

They both smiled, the youth with an open face, the girl something close to the Mona Lisa’s. “You probably think we have got lost from a stage or film set,” the youth said, his voice, lilting, light and cheerful in much the way Errol Flynn’s had. “These are our normal clothes. We have decided to escape the twenty-first century and live in the past. It seems the only way to feel happy in the twenty-first century. We started by writing a book about Robin Hood and Maid Marian and then decided to live that way in the woods.”

It turned out that they had their own cabin near Alan’s. They mostly got their food in town though the youth whose name was Robin did get food from hunting in the woods and fishing in the sea.

“Have you got a band of merry men?” Alan asked.

“No, just us,” Robin said, with a gay laugh. “And persons like you.”

Alan felt honoured to be included.

“We have a boat and are ready to cast off once the borders open,” Robin said as he, Marion turned out to who turned out to be French, her name Marianne, though she been travelling back and forth across the Channel as Alan had until the virus came and put an end to freedom of movement.

They sat down with Alan and they enjoyed together fresh strawberries, the first of the season,, kefir and cider, the champagne of the West Country.

They began meeting together on a regular basis. One afternoon, they were together when the police came, a lean male with a round ring in one of his ears with a tattoo next to it, a chunky female with her yellow hair pulled back, dressed in black with chains attached to their belts, giving them an element of sado-masochism.

“What are you doing here without masks and not distancing?”

“We live in the same household,” Robin explained.

“You look as if two of you are some kind of theatrical band,” the policeman said, his voice suspicious.

“We are” Robin said.

The policeman looked at the policewoman in a rather helpless way as if she might be able to toss him a life-saving belt. She looked back at him with an indifferent way that indicated she would rather be consulting her smartphone. Technology had replaced personal ingenuity.

“Put your masks on,” the policeman said. “They are there to keep us all safe. And take your vaccine when you are invited to.” He spoke in the voice of impotence, disguised, masked, in authority.

Robin leapt up and raised his hand to his voice in a salute, “Aye, Aye, sir,” he said and then, bowing to the policewoman, he said, “and you, fair policewoman.” The latter looked at him, her dulled brown eyes showing a muted sense of curiosity.

Marianne looked at Alan in a smiling look at indicated a sense of complicity that gave him hope, that best comfort of our imperfect condition as the historian Gibbon wrote. Her smile indicated to him that she might be open to him, notwithstanding her link with Robin.

He was at his old-fashioned typewriter the next day when there was a tentative knock at his door. Who could that be? He went to open it, fearing that it might be the police or an assassin from Daffodil. Instead it was Marianne. She seemed smaller than she had in the woods and he noticed the freckles on her face as well as her green eyes which he liked to think matched his own. She had a basket of apples, some of them red and some green, spiced with raspberries, in her hand.

“I brought these,” she said. “We are neighbours and I had a feeling that you might be alone.”

Alan invited her to come in and she agreed.

“What a lot of books,” she said, looking around with open wondering eyes. “No television.”

“There is a little laptop but I prefer to be discreet about it.”

“Very good,” she said. “I could enjoy living in a place like this.” She had a voice that was attractive as if it was curious. “You are amusing” she said.

He made a herbal tea of turmeric brew that included ginger and cinnamon as well as turmeric and they drank in, sweetened with wild honey and goat milk.

“I liked you at once,” she told him. “I like Robin and I like you. You are different. On the whole I could be happier living with you than with Robin. You need me more than Robin does and you seem to like a quieter life which suits me.”

Marianne stayed the rest of the afternoon and then the evening and night. Her presence gave Alan a sense of contentment that he had not known since he had been able to see Corrine. With Marianne at his side, he was less fearful of the Virus police knocking at his door and ringing him on his primitive mobile to ask if he had yet had his vaccine. Marianne was as reluctant as he was to have a “jab” and no less sceptical of ifs efficacy. The aged Queen had called in her creaking voice for all of her loyal subjects to have the jab: “Think of others and not of yourself.” It was the first time in which she had expressed a public opinion during her decades of reigning over her subjects who extended beyond her island to a commonwealth. She seemed to be reading from a script. So too did the representative from the Health Centre that called Alan. “You should be thinking of others and not of yourself. You should be protecting others of this dangerous and contagious disease that have killed so many people.”

Alan dodged the question by saying he would think about it. He couldn’t think of anyone he knew who had died of it. There may have been people whom he had once known and lost touch with who had perished of it. He had lost touch with so many people he used to know and now missed to various degrees. We were all supposed to be in this together but he could have been fooled about that since it seemed hail fellow, well met as far as he could see. He was too isolated and that made him the more hopeful that Marianne would stay with him.

“France is the centre of resistance to the vaccine,” Marianne told him. It was another reason for wanting to be in France. There were more people in France doubtful of it just as there were less customers there for Daffodil pf Daffodil Cut, Daffodil’s streaming service whose trucks roomed England’s roads just as it did those of America and as far away as Africa and even the jungles of Latin American. At the same time, France was rumoured to refusing unvaccinated arrivals. It was one thing not to be vaccinated if one was in France and another if one was returning there from abroad.

Marianne disappeared some days to be with Robin as he hunted in the woods. In these moments of her absence, Alan missed her, less for the lack of her presence than for the fear that she might not return. She always did even if she was often late. She and Alan began writing an historical novel called Bretonside about the moment in 1403 when Breton marauders had landed in Plymouth to take Cornwall and link it to Cornouaille in Brittany. Marianne herself came from the Loire region, the douceur angevine of which the Renaissance poet, du Bellay, sang.

“I fear the vaccine more than the virus,” Alan told Marianne.

“I don’t think we shall have any choice,” she said.

It was a frightening thing. Babies were being vaccinated as soon as they left the womb to enter the world. Some babies seemed reluctant and cried wildly. Many were encouraging what was called retrospective abortion in such case which meant doctors or nurse smothering the new-born infant when the parent agreed that it was going to be a bad citizen. There was also increasing support for what was called “assisted dying,” better known as euthanasia. Members of the medical profession were being told that they must put aside the Hippocratic Oath, now considered to have been conceived in a time of white Supremacy, racism, colonialism and imperialism.

At any rate, there were few cases of retrospective abortion since there were few people being born. Social distancing and social media discouraged sexual intercourse and many young white males, trained to be ashamed of their sex and race, were almost as impotent as their aged, worn-out grandfathers. Babies were being born to members of the coloured races were babies were symbols of pride rather than nuisances.

Robin went up to London to answer a casting call for a new television series about Robin Hood to be produced by Daffodil Cut. He was turned down for the part of Robin Hood which was to be portrayed by a black actor since Daffodil believed in diversity except when it came to its board of directors. He was told he might be used as a villain since the Robin Hood in the series would fight racism, sexism, colonialism and strive to end climate change. The directive had come from Zed Nero himself that Robin Hood might keep up with the times and must work towards what Nero called the Great Scam. “Above all, our Robin Hood is very anti-White Supremacy,” Nero said.

“It is enough to make me want to go to Seattle and assassinate Zed Nero,” Robin said. Alan and Marianne laughed but also looked through the windows just in case someone might be lurking about and hear what was being said. Until recently, England had been a place where any flippant joke could be said without fear but this was no longer the case. Robin’s bow had been confiscated and he had been charged £1000 in fines. “Things have changed since the Middle Ages,” the judge had told him. Robin was now watched. The news that Robin Hood was to be portrayed on the world’s television as a Black Lives Matters activist, angered him. He itched to get on a skiff and sail somewhere in search of freedom. But where to go? It seemed every place was now locked up. He thought of travelling the world as a one-man show of the “real Robin Hood” but public performances were banned until further notice.

Robin was at Alan’s when a knock on the door. It was the police dressed in black and again one male and one female though a different pair than the previous couple. “We understand you still haven’t had your vaccine,”

“The hell with your vaccine,” Robin said.

“I’m afraid we can’t agree with that attitude,” the male constable said whose bare arms were covered with tattoos. “Non-compliance with public safety measures is now against the law.” His female assistant was taking out a box of medical equipment as the policeman spoke. “Now I am obliged to ask all three of you to roll up your sleeves. Everyone has to have a jab. No excuses or exceptions. It’s the law.”

“I am sure it is not the law,” Robin insisted.

“It may not have been in the Middle Ages, sir, but one or two things have changed since then and much for the better if I may say so. Now enough of this unless you prefer to have your jab in prison.”

“Everyone feels better with a jab,” the policewoman said. Alan, feeling helpless and impotent, noticed that the legend on her box read “Daffodil.”

“I don’t want this,” he said in a voice that was gentle even though he was seething inside.

“You wouldn’t want the virus either,” the policewoman said which was undeniable.

It was done in a moment. Alan felt his arm growing numb. Robin, still resistant, was in handcuffs which had always been manufactured in Daffodil’s plant in China.

Marianne looked at Alan. “I feel not too bad so it must have been the Viper rather than the Astro-Zapper which puts people in the hospital.”

Alan now felt a certain pain which went beyond his wounded resister’s pride.

The days come, some of them fair, and some of them grey with rain. Alan and Marianne lay together, drowsy and listless, not dead and not entirely alive. The vaccine may have given them a boost of immunity but if had also taken away from them a good bit of gumption. Reading, even the lightest books, until the day before the vaccine was shot in their veins, the greatest of pleasure, was now a chore as challenging as pushing up the boulder to the mountain was to the hapless Sisyphus. It was enough to make them turn to television had there been one available in Alan’s cabin. They could just about manage to stumble out to the town for food and drink. They would walk to the sea in the hope that its air would burst some life into the numbed veins. To no avail! A half-life passed in a state of drowsy somnolence.

“Now that we are vaccinated, we could go back to France,” Marianne remarked one day three weeks after the forced vaccination, in a slurred voice.

They agreed that it seemed much too much work. Everything was now too much work except sitting next to the sea or in the house and watch the fire burn. It was a peaceful life but it was not what they had hoped for in the past.

An article in the local newspaper announcing the death in prison of one Robert Hoodlington, famous in the area for dressing up as Robin Hood, depressed them both.

Meanwhile in his underground compound in Seattle, Zed Nero was sitting in front of the panel board of television screens that allowed him to zoom into all of the houses of government throughout the world as well more discreet places were international grey eminences—of which Zed Nero was foremost—lurked.

“The vaccine is triumphant throughout out the world,” he said to his friend, Chairman Zi, head of the Chinese Communist Politburo. “Now to the next final stage.” The two men smiled at each other in a suitably ghoulish way.

__________________________________

David Platzer is a belated Twenties Dandy-Aesthete with a strong satirical turn, a disciple of Harold Acton and the Sitwells whose writing has appeared in the New Criterion, the British Art Journal, the Catholic Herald, Apollo, and more.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast