The Master of Zeehorde

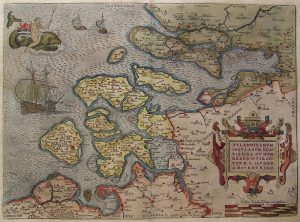

The county of Zeeland, 1580

by David Platzer (March 2022)

In the fifteenth century, the small city of Zeehorde, today a relic dependent on tourists for her survival was a flourishing port, an equal and rival of Venice, Bruges, Hamburg and Ghent. Ships and boats bearing cargoes of jewels, spices, minerals, wines, silks and wool came from all over the known world to her harbour on the coast of Western Flanders. Every European nation had representatives in Zeehorde, every Occidental tongue and others more exotic and from lands beyond the waters of the West could be heard in its Grand Place, the nearby Stock Exchange and in the surrounding streets. The city seemed to have been built on water, a Northern Aphrodite. Beside the canals which criss-crossed the city could be seen not only the plumed and wing-shaped headdresses of Burgundy but also the scimatared turbans of the East. The Turk might be no less feared in Zeehorde than he was in the other capitals and provinces of Christendom; nevertheless, the town’s merchants and traders found him less threatening as a trading partner than an adversary in war. Zeehorde’s attitude towards Jews and Moors was no less tolerant: for these races, increasingly unwelcome in their former havens of Spain and Portugal, were finding new quarters in the Northern city. In Zeehorde, they were allowed to live as they wished, practice their religion and avoid any intercourse other than the commercial with the pork-eating Christians.

The rugs and silks brought to Zeehorde by the Turks and the Moors, the knowledge of diamonds and the skill in their cutting by the Jews, were only additional seasons in an already highly-flavoured mix. Visitors were invariably bewitched by the fine clothing of silk, brocade, lace and wool worn by the Zeehorders. The city’s streets seemed lined with precious stones as if the sea had brought treasure buried for centuries in the swirling folds of her waters and deposited it at Zeehorde’s feet. The climate, typical of Northwestern Europe with its frequent, gentle rains, its fogs and its mists, invigorated rather than diminished vitality.

Zeehorde’s beauty was less striking at a time when cities everywhere were beautiful than it is now when ugliness is the norm. Most building was then in brick or wood rather than in stone. Zeehorders possessed an exuberant love of colour: their buildings wore of bright hues of brick red, salmon-pink, yellow, glazed white and purple. The interiors of their houses were often more sombre, of dark oak or wood panelling, allowing for exquisite carving in what we now call the Gothic tradition. At the fifteenth century progressed and Zeehorde’s ties with Spain grew closer, the burnished gold of Cordovan leather appeared on the walls of many houses in Zeehorde. Even the narrowing buildings in the poorer neighbourhoods had their beauty: their conditions as those prevailing in the houses of the rich might strike us today as primitive but they had a grace and style.

The charm of Zeehorde’s habitations was matched by the magnificence of her public monuments, her town hall with its stone statues of the Counts of Zeeland standing in niches of that citadel of Zeehordian commerce, the Stock Exchange. Even more impressive, evidence that the Zeehordians rendered to God what was His, were the city’s churches. Of these, the most notable, Zeehorde’s pride, was her great cathedral. Greatest and loveliest jewel of a city rich in jewels, the cathedral reminded the Zeehorders that the pomps and vanities of this world would pass and crumble into dust. The cathedral’s construction had begun at the end of the thirteenth century. Two centuries later, the body of the church was complete; nevertheless, men still mounted giant scaffolds to work on the tower, a stalactite which seemed to soar as close to heaven as anyone could imagine.

This was still the age of gothic, even though nobody used the term at the time. Even so, word was beginning to spread in Zeehorde, by the many Italians resident there for reasons of business and also by Zeehorders who had been to Florence and Venice, of new developments in Italian art. These reports made some Zeehorders wonder if their own artists and craftsmen were not a little old-fashioned in their techniques. The Italians had abandoned those spires and pinnacles with which they had never been entirely comfortable in favour of forms derived from the classical Roman architecture which was in their blood. That the gothic might be no less native and natural to Zeehorde as the classical was to Italy did not occur to Zeehorde’s more impassioned advocates of the Italianate. The saints of the New Testament and the prophets of the Old, standing so firmly in place on the portals of Zeehorde’s churches, their arms clasped to their sides as if fearful of occupying too much space might have their beauties, Italophile Zeehorders would say but once one had seen Donatello’s statues in Florence, they seemed stilted. The Florentines did not cram their statues or did they force them into rigid poses. Each statue was given room.

Such comments came more often from Zeehorders than from Italians. Indeed, Italian artists and patrons were more often interested in Northern art than one might gather from Vasari’s chauvinistic pages. Often, a Florentine, a Genoese, a Venetian, a Sienese or a Lucchese would commission a painting from one of Zeehorde’s able masters. Even so, artists and patrons of Zeehorde wondered more and more if there was not something barbaric and backward in their traditions. The bolder among them began to make attempts to assimilate what they could discover of Italy’s classical heritage into their own techniques.

Albercht Lanchvue was aware of and interested by everything he saw and heard of Italian art. His reputation as Zeehorde’s best painter brought him large numbers of commissions from Zeehorde and abroad. These he satisfied promptly and invariably to his patron’s delight with the help of his studio of apprentices and assistants. His renown was such as to allow him to live in a house on the Langengracht, one of the most fashionable canals in Zeehorde. Though only a few minutes’ walk from the Grand Place, the Langengracht seemed a different world from that of that bustling, hectic meeting-place. Along its tree-lined way, the only sounds to be heard were those of tranquil domesticity, of water plashing gently in the canal, of servants going about their work, a housemaid sweeping the area round the house, a tradesman’s cart slowly moving up or down the cobbled street, now stopping at a door to make a delivery, now moving on again with a shaking of the reins and a horse’s grunt. Sometimes, two or three men or women would be walking beside the canal, sometimes a solitary stroller.

It was not usual for artists, still generally regarded as artisans, to live on streets like the Langengracht. Giotto in Italy or more recently Jan van Eyck in Bruges who had accumulated fortunes and developed great reputations were exceptional cases. Albrecht Lanchvue’s prosperity was such as allow him on occasion to ask clients who had access to these treasures to pay him in Italian paintings rather than in money.

On a recent occasion, the Zeehordian representative of the Medici Bank had given him a painting of Venus by the Florentine painter, Botticelli. Albrecht’s feelings about Botticelli were mixed. At first, he found Botticelli’s depiction of Venus too delicate for his robust taste. What he had seen of Venetian art, which took more emphasis on colour than line, its vivid sense of pageantry and its appeal to the senses, was more congenial to him. Nevertheless, Albrecht liked this example of Botticelli’s work and especially his mythological paintings which, with the exception of this Venus which he was told had been a sketch for a much larger painting, he knew from copies. Botticelli’s Venus gave Albrecht an example and an inspiration spurring him to produce something of his own.

Botticelli’s Venus was one of the few paintings Albrecht knew representing the unclothed human figure. Albrecht had made his reputation painting altarpieces and portraits: to these, he added the bread-and-butter work of colouring statues and on the facades of buildings. He could paint the folds of robes so that every line and crease showed. No blade of grass was so slender as to defeat his acute eye and dexterous hand. An air of vagueness belied a talent for subtle observation and a skill for painting portraits combining insights into the subject’s nature with a way of flattering his or her vanity. Nevertheless, he was restless. He had painted many almost nude Christs in religious pictures. Now he wanted to match the Italians with mythological scenes.

The Italian absorption in problems of perspective amused him. It was approached in so theoretical a way. While Florentines busied themselves with mathematics, Northern paintings learnt perspective through practice rather than study. Albrecht was certain he could master the nude in the same way. Painting Christ in pictures of the Baptism or the Resurrection had given him some experience; in these pictures, however, he worked from an idea rather than something before his eyes. Jan van Eyck had painted a nude Adam and Eve and a woman bathing, the nude was still to be explored in the North. There was little demand from patrons for illustrations of the pagan myths of classical antiquity and a strong strain of humorous realism impeded idealized representation. Zeehorde’s burgesses were conventional in their choices of subjects: fearful for the fate of their souls, they tended to commission religious scenes with themselves kneeling in prayer.

Albrecht did not worry: the opportunity would come. Meanwhile there was nothing to stop him preventing painting and drawing in his spare time. Mastering the nude would help him in limning clothed no less than unclothed figures. Despite his fame, Albrecht was never satisfied with his work. He was always pushing himself. No matter how he advanced, he could never progress as much as he wished. He covered pages and pages with drawings.

His female model of preference was his wife. Marguerite was a tall, voluptuously big-boned woman with long, fair hair and vivacious blue eyes the colour of hyacinths. Her cheeks were round with a ripe pink freshness, her mouth was generous and full. Her breasts were firm, her nipples small as cherries. Albrecht had used her as a model for his Virgins when Mary was still a young woman playing with joy with her child. For pictures of the Virgins at later moments, those of the Crucifixion or Resurrection, Albrecht found that Marguerite lacked the required depth of feeling. She was too much a woman of this world for that.

Conventionally pious, Marguerite was also unabashedly fond of fleshly pleasures. She minded not at all posing nude for her husband. Her only grudge arose from her feeling that he was seemed more obsessed in drawing or painting her than in making love to her. And indeed Albrecht, who lived for his work, did indeed regard from more important concerns. It amused him to make an engraving of himself as Adam and Marguerite as Eve in the Garden of Eden. The lush vegetation, the precise and botanically exact depiction of the various fruits and flowers, the birds and beasts with which he surrounded his figures were rendered with his usual precision, the nudes with a delight in the human form absent from art since the time of the ancient world.

It was ancient mythology which he knew would offer him the most scope for the portrayal of the nude. It was not long before he found the patron he desired for this work. His Maecenas was not a new one: the Count of Zeeland had provided Albrecht with many of his most important commissions. For Zeeland, Albrecht had made the original designs from which a great series of tapestries were then woven to decorate the walls of Zeeland’s country house outside of Zeehorde. Albrecht had painted altarpieces for Zeeland’s chapel and devotional pictures for the private use of the Count and Countess. The miniatures in the Countess’s Book of Hours had been hand-painted by Albrecht. Likenesses of the Count and Countess as well as of each of their children were limned by Albrecht in addition to the portraits of them he included in religious pictures, sometimes kneeling in prayer, the Holy Mother and Child, sometimes in the guise of saints or even as members of the Holy Family. The Count was a man who treasured his little joke. For his pleasure, Albrecht painted a Virgin with Saints, giving Mary the ravishing features of Zeeland’s favourite mistress, Isabelle Chartier, and lending St. Elizabeth the plainer looks of the Countess. Isabelle Chartier was proud of her beautiful breasts and so, Albrecht portrayed her for his patron with one breast exposed as Mary nursing the Infant Christ.

Though a robust man with a taste for venery in both sense of the word, the Count of Zeeland conformed in appearance to the tall, thin ascetic type of the late Middle Ages. His face and figure had a delicacy which would be absent from the looks of the princes of the succeeding generation, the bearded, lusty figures who possessed elements of the bull and of the satyr, Henry VIII, Francois I, to some degree even the Emperor Charles V. Everything about him was long from his face to his nose to his hooded almond eyes to his long tapering fingers. His body with its smooth shape encased in doublets, tunics, capes and leggings conformed to the face. So too did his feet shod in curling slippers slithering beyond his toes like tendrils. His thin mouth seemed that of a monk’s rather than that of a soldier’s, a lover’s and a connoisseur’s. It was astonishing that so unremittent a sensualist should have the look of an anchorite. And yet perhaps not, for the Count of Zeeland was a religious man, his faith of a piece with his love of beauty and his enjoyment of the flesh and the hunt. He lived in an age when men and women worshipped and believed in a God who made allowances for human frailities. Did not their religion teach that all mortals were sinners? It was only with the Calvinist and Puritan offshoots of the Reformation that tighter jackets would be imposed.

The Count’s estates were in the country, but his town residence was on the Heerengracht, the canal next to the Langengracht. Country life with its hawking and riding was his principal pleasure as well as his foremost responsibility for the Count gave close attention to the affairs of his land. Even so, the Count also enjoyed the liveliness and gaiety of the town: Zeehorde’s pomp and splendour amused him.

He enjoyed his visits to Albrecht. He liked the painter’s house with its glazed windows through which thinly filtered light flowed, he enjoyed Albrecht’s studio which stood in a long, bare room at the back of the house looking out onto a garden and court. There was a smell of paints, oils and other fluids necessary to the master’s craft that the Count found pleasurable. He liked too the pictures stacked in rows against the walls, an easel, the wood-backed chairs and the plain wooden table, scuffed and smeared with stains made by drops of paint. At the entrance to the room, there was a balcony set above the door where Albrecht sometimes had a musician play as he worked: the master’s muse was susceptible to sweet strains.

“How I love this room!” Zeeland said as he entered, inhaling the studio’s peculiar smell with the same gusto a town-dweller takes in filling his lungs with the fresh mountain air on a rare excursion to the country. “What a thing to be a painter!” he continued. “I should enjoy such a life. Or perhaps a player. Never a banker or a merchant. Perish the thought! Such people bore me with their petty, counting-house minds and base jockeying for position. Well, I suppose they are necessary evils nowadays and one must humour them. The world is what it is! What interests me more is having a series of paintings done by you for my pleasure.”

“And what might be the theme of this pleasure, my Count Zeeland?” Albrecht asked.

“I am not certain of the individual subjects,” the Count said. “I know that what I am about to propose may be something of a novelty. However, I have the greatest confidence in you, so great that I cannot believe anything in the realm of painting is beyond you.”

Albrecht bowed in gratitude.

“Of late, I have been amusing myself with reading the ancient Roman myths,” the Count continued. “It strikes me that these tales offer the most wonderful possibilities of illustration. I know that in recent years, painters in Florence and Venice have been painting mythological scenes. Of course, this kind of thing is part of their heritage and comes perhaps more naturally to them than it would do a Northerner. Nevertheless, I suspect you might enjoy such work. As I say, nothing I have ever asked of you has proved beyond your capabilities: indeed you have invariably surpassed my expectations on every occasion.”

“You do me great honour, my lord,” Albrecht said. “What you propose is not only to my liking but indeed comes as fulfilment of a wish long-nourished in secret.”

That the Count of Zeeland would enjoy paintings of the nude was apparent to the painter. Albrecht decided to show Zeeland sketches and drawings he had made of Marguerite. Most men would have hesitated to show another man pictures of their wives nude; for Albrecht however, it was the work of art that mattered: the woman herself was no more than the raw material for the finished product of his hand and eye. In any case, there was no patron to whom he so enjoyed showing his pictures: to see Zeeland handle the sheets of paper, the blocks or the boards with the same tenderness a woman uses in fondling a child warmed Albrecht’s heart.

“But this is extraordinary!” the Count exclaimed as he looked at the pictures. “I have seen nothing that pleases me more, not even in works I have seen from Venetian painters.”

“You give me more than my due, my Count,” Albrecht said.

“I give you only what is yours,” the Count replied, holding up one of the drawings to the light. “When I look at this woman, I see Venus. Isabelle whom you have painted so well would be perfect in certain mythological scenes. But one likes a certain variety. What I desire is a series of six mythological scenes showing the loves of the gods and goddesses for my hunting-box in the country. As I only invite my intimate friends there, you may paint with a licence you might hesitate to use in work intended for more public places.”

No sooner than Albrecht had a commission, he went to work at it. At once he began to plan his series. Before his departure, the Count told him that Isabelle would be available to pose for him and that Zeeland expected her to figure in several of the scenes. Albrecht decided that he would include Marguerite as well. Isabelle was young, only in her twenties. Albrecht could see her as Danae, Io or Psyche. For Juno and even Venus, Albrecht would employ Marguerite, in her early thirties and older and riper than Isabelle. As for the male figures, he could use himself for Vulcan, Neptune and Zeus himself. For the more youthful figures in the series, for Paris, Adonis and the god Apollo, he would need a youth whose beauty equalled the female models. None of his apprentices, nor any of his household servants, qualified. He must seek elsewhere.

It was the warm season of the year. Albrecht who worked every day from the early morning after Mass to the early evening, made a habit of following his midday with a short stroll. He found that this brief interruption refreshed him and renewed his energy for his afternoon’s work. The hour was one when Zeehorde was less bustling than usual, especially this season. The weather was not only warm but fine: the sun had shone for days, a rare spell of prolonged dry weather. This was the season when repairs were made to buildings, houses and streets.

Even in the hot weather, men and women wore their best clothes. The heat of the sun was considered as dangerous as the night air. Albrecht was surprised to see a young street paver at work that afternoon, his white linen shirt, tied around his waist, leaving the upper part of his body exposed as he did his work. The youth, aged nineteen or twenty years of age, with tawny hair falling in curls round his fresh face, impressed Albrecht as the model he needed. The composition of Venus and Adonis with this youth, his muscled rippling up and down his back, came to him. He could see Marguerite-Venus imploring him to stay rather than flee him to his fatal hunting. Albrecht decided he would ask him to pose for him.

The work was hot and the boy, tired from his labour, put down his tools for a moment to mop his forehead. Rivulets of sweat ran down his back and chest. He saw Albrecht coming down towards him. The boy assumed that Albrecht must be a patrician of Zeehorde. The idea pleased him. Paving streets was irregular work and the boy, his name Jan, was not averse to earning money by other means. The patrician might ask him to work in his house; he might also give Jan money to sleep with him. Jan, who had grown up in the promiscuous atmosphere of the poor, did not mind engaging in such commerce. It gave him money to spend on girls he liked or drinking in taverns with his friends.

Jan was disappointed when the patrician revealed himself to him to be a painter. Jan, a labourer who could not even consider himself an artisan, had no great opinion of painters. The idea that painters practiced a liberal art was not yet current among Zeehorde’s working classes. A painter such as Albrecht, rich and renowned as he was, they regarded merely as an artisan.

Nevertheless, Jan could not but he impressed when he heard that the painter had a house on the Langengracht. The kind of work that the painter proposed struck Jan as strange; even so, he was willing to accept it provided he was paid. He had no work the following week and the money which the painter promised him sounded good to him. He was even more pleased when the painter said he could spend the night in the house. To Jan who lived with his family in Zeehorde’s poorest quarter, the prospect of a night in the Langengracht was enticing.

Jan had a great deal of experience with women. His attitude towards sexual relations was instinctive and uncomplicated. He had a sense when a woman was attracted by him. He tended to take advantage of the opportunity, hesitating only when he feared it might lead to an entanglement.

Jan sensed at once that the painter’s wife was interested in him. His first glimpse of Marguerite came when he entered the house to begin his day of posing. She was standing in the hallway talking to one of the maids. At first, he was not sure of her position in the household. Her clothes were fine and her face beautiful; however, she lacked the distinction and gracious bearing he had seen in women he regarded as ladies. When she spoke to her maids, she betrayed a mixture of uncertainty and roughness which indicated she was unsure as to whether she would be obeyed. But this was painter’s house. The painter could pass for a gentleman but his wife might not be more than a butcher’s daughter. Jan could tell she had a fine figure and something in his loins told him that she wanted him as much as he did her.

Posing was not work which Jan found agreeable. He disliked spending hours without moving. He was a physical creature, used to an active life. This staying still in an unnatural and tense position, his body frozen as one in the process of hastily departing, something he wanted to do and was not allowed to, tired him more than hard labour. By mid-morning, Jan was willing to go back to street-paving; by midday, the attractions of breaking stones had become more obvious.

The way the painter looked at him made uneasy. He didn’t mind when people regarded him with lust. To be studied with complete indifference as is he was a chair or a candle irked him. The painter’s blue eyes he found cold and unsympathetic. No wonder his wife was inclined to other men. Every so often the painter would tell position. Some of these stances caused Jan great discomfort yet the painter showed no pity. His absorption in his painting was entire. Jan could not understand that the painter’s great concern was in the vision before his eyes: so elusive was it that he had to give it his complete concentration so he could transcribe it. The human beings he used as models were tools to him, at least when he was at work.

Jan failed to understand. Painting meant little to him and he resented being used in this way. For several hours, the painter forced him to hold the same crouching posture. Jan’s back, arms and legs ached in a way rare to him. At one moment, he could not bear it and he let himself go without intending to. The painter snapped at him. Jan swore at him under his breath. He imagined himself in bed with the painter’s wife as much in revenge as for pleasure. Their bodies would entwine in delight. Perhaps that compensation would not be granted him. The painter’s wife might enjoy teasing him just as her husband tortured him with these poses. It did not matter all that much to him if his idea of the painter’s wife came to nothing. There were plenty of pretty girls in Zeehorde. The painter’s wife would be a reward for this painful work.

The day ended. The painter nodded with a faint, diffident smile at Jan and gave him a gentle, affable thanks. “See you tomorrow,” he said. He knew that Jan would be there the next day and would be grateful for the money. The painter arranged that that his model should be given not only lodging for the night but also that he would be given meals in the servants’ quarters. The food was abundant and the drink copious. Jan found the servants good company. He wondered if he might not like to be a servant himself. The work would be easier and steadier than his haphazard jobs. Servants were the patricians of the labouring classes and regard themselves as such. Nevertheless, Jan had his doubts. He liked his freedom. He liked the idea of going into the country only half an hour from the centre of town and hunting his food in that way. He liked seeing his friends in the taverns he frequented. They were young and work they had to do in the morning did not prevent them from staying up all night, drinking and singing. In the whole, he did not want to settle down yet. Perhaps in a few years…

After the meal, Jan was shown to the room he was allotted. There was a large bed and yet Anneckje, a pretty maid, informed him that he would be alone. This displeased Jan. His time valued privacy less than ours does and Jan was used to the serried quarters of the poor. The room was more comfortable than any he had ever known and he felt wretched in it. Before Anneckje left the room, Jan took her by the waist and tried to plant a kiss on her mouth. Laughing. She turned her head and the kiss landed on her cheek. “I have a fiancé,” she giggled. “He would kill you if he found out.” Mischievous little minx, Jan thought. Jan thought of the painter’s wife. That was a woman. She was older but Jan could appreciate ripeness and experience. She would be good in bed, he was sure of it. She must be upstairs, he thought to himself but where he had no idea. Feeling disconsolate, aching slightly from his day’s work of posing and not looking forward to the next day, Jan blew out the candle and slipped between the crisp, clean sheets.

He had just fallen asleep when he heard a knock at the door. Getting out of bed, lighting his candle and pulling on his breeches, he was astonished to find the painter’s wife at his door. She was alone and held a torch. Its light indicated her smiling face which looked beautiful and perhaps more so in the contrasting shade. He felt desire in his groin. She was dressed only in a thin, white gown that allowed Jan to glimpse the form of her body including her firm, magnificent breasts.

“Oh!” she said, giggling at the sight of Jan’s bare chest. It was clear, however, that she was not shocked.

“I am sorry to disturb you at this hour,” she said in a whisper that had more of a hint of coyness to it. “You see I have something in my room which needs to be moved and I thought you might be able to help. You look such a big, strong man.” She ran her soft, delicate hands up and down Jan’s muscles and then his chest. Jan felt shivers ran through his body. Inflamed by desire, he pulled her into the room, took the torch and put on a stand. He grabbed her body to his and kisser her hard on his mouth as he ripped her gown to crush her body to his. The light was strong enough to allow him to see her face which was transformed in rapture. Her breathing had become a pant. “Come to me!” she said.

“This room is so small,” Marguerite said a little a later when they were in each other’s arms. “Mine is much larger.”

“But what about your husband?” Jan asked, feeling uneasy. Sure as he was that he could handle the painter who was much older, he did not want to lose his second day of work that would give him money, a commodity essential to him. He had his pleasure and that was enough to make him tire and also uneasy about Marguerite. He had found that women could not always be trusted.

“My husband never comes to my room unless I ask him,” Marguerite said. “He is sound asleep, I listened at his door before I came down here. He is a strange man, passionate for his work which matters to him more than love. We make love every Thursday and that satisfies him.” She began to caress him with her soft, beguiling hands. It worked. Jan was young and strong enough that hardly had he finished making love than he was ready for more.

“Before in my bed rather than in a servant’s,” Marguerite said.

Jan suspected it was a trap. She might be trying to make her husband jealous. He did not imagine that she really cared about him. Nevertheless, ready to accept his fate whatever it might be, he went with her. Marguerite’s room was of a luxury beyond anything he had glimpsed in his life. The bed was large and covered with a canopy and curtains of crimson damask. The windows were glazed, their outer wooden boards shut and there were tables and chests of gleaming dark wood. The air was scented with balms and spices. The sheets were of silk and of a softness equal to Marguerite’s flesh.

There seemed to be nothing in the way of a trap during their night of pleasure. As the light of dawn appeared through the closed windows, Marguerite expressed regret that it was likely to be their only night together.

“Our lives do not match,” Jan said. “I am happy in mine, rough as it is and I doubt you will be ready to abandon yours of silk sheets and beautiful things for the little I could offer.”

“We could use a footman in this house,” Marguerite said. “You seem to get on well with the servants. Life here is surely better than that which you know. You will not always be as young and strong as you are now.”

Jan thought about it. The life of a servant in a rich man’s house, even if the master was only a painter, would probably more agreeable than his present existence of odd jobs and hard labour. He enjoyed his night with Marguerite, but he was wise enough to sense that it was not something he would be able to maintain if he was living in the house as a servant. The other servants would notice and would talk. He could end up in the street and this time with a mark against his name. Add to this danger was his sense of freedom. In ten years, perhaps five, he might be ready to settle down but not yet. The opportunity had too many clauses added to it.

The second day of modelling was even more painful for Jan than the first. Marguerite had assured him that the painter could not discover their secret, but Jan was not so certain. The painter’s eyes were so acute that it was hard to think of his failing to detect anything. Or perhaps the painter was as indifferent as his wife claimed. The painter seemed so strange to Jan as to appear not entirely human. The couple did not appear to have children. That too seemed strange.

Some distraction was provided during the session by a lutenist who Albrecht sometimes invited him to play for him while he worked. The melodies he played were sometimes melancholic with an element of gaiety. Jan liked them less than the more raucous tunes he enjoyed singing with friends in taverns. Jan wished he played an instrument. Later, an actor came to read stories in verse to the painter. There was one from Ovid about Venus’s love for a mortal, a youth more devoted to hunting than to the goddess’s divine embraces. Venus, foreseeing her lover’s death if he went out to hunt in the fields, begged her to stay with her. Jan, listening, understood the youth’s feelings. He loved hunting too though he was sure he would never let an animal get the better of him.

At the end of the day, the painter put down his pencil and chalk. “I think that is all I need from you,” he said in his quiet voice. Albrecht, having filled pages of sketches of Jan for his Venus and Adonis, was as satisfied as he could be. He would use the youth as well for a Judgement of Paris, a painting which would be of particular interest to him for the experiments he intended to make in the rendering of flesh tones and the different effects of light and shade on them. He fancied that he had ideas which about technical effects that occurred to no other painter.

“You have been patient,” the painter said to Jan. “I cannot imagine the work was amusing for you. Still, a meal awaits you. You can stay the night in the same room if you wish. I have already spoken to my wife and the servants.” The painter placed a pouch of golden coins on the table. The money was more than Jan had ever earned for two days’ work before. The painter might be an odd and frosty fish but he was a generous one. To work in his house might not be disagreeable.

Marguerite came to his room again. She asked if he had made a decision.

“I shall have to think about it,” Jan said.

“What is there to think about it?” she asked with undisguised disdain. “You have nothing. I am offering you something to take you off the street.”

Her nagging angered Jan. He now longed to escape the house even if it was the only chance he would ever have.

“How can you leave me?” Marguerite asked. Jan shrugged. He suspected she was a woman of the burgess class who wished to imagine herself as a great lady. She knew how to make love but he knew she would throw him aside when she had no more use of him or if he became a nuisance to her and her position.

Walking beside the Langengracht, Jan felt a great sense of liberation. The sun was shining, the day would be fine. There would be many more such days in his life. He could not imagine the possibility of his death.

Neither Albrecht nor Marguerite heard anything more of the youth who lived on another side of town and briefly entered their lives. Perhaps one of their servants in the market heard of a young man who was gored to death by a seemingly gentle animal in the fields out of town. For a few days, there was talk of this gruesome death. It was soon forgotten except for the youth’s family, friends and a baker’s pretty daughter who had been fond of him.

The son who was born to Marguerite some months later grew up to be a disappointment to Albrecht. He expected him to become a painter like himself. Instead, the boy cared only for hunting, cards and girls. He tried to paint but it was clear he had neither powers of application nor a modicum of talent. Albrecht’s series of the loves of the Gods proved a far more satisfactory offspring. It can now be found in a room in the Royal Museum of Brussels.

__________________________________

David Platzer is a belated Twenties Dandy-Aesthete with a strong satirical turn, a disciple of Harold Acton and the Sitwells whose writing has appeared in the New Criterion, the British Art Journal, the Catholic Herald, Apollo, and more.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast