The Miracle of the Mayflower: Celebrating 400 Years of National and Family Roots

by Jeff Plude (November 2020)

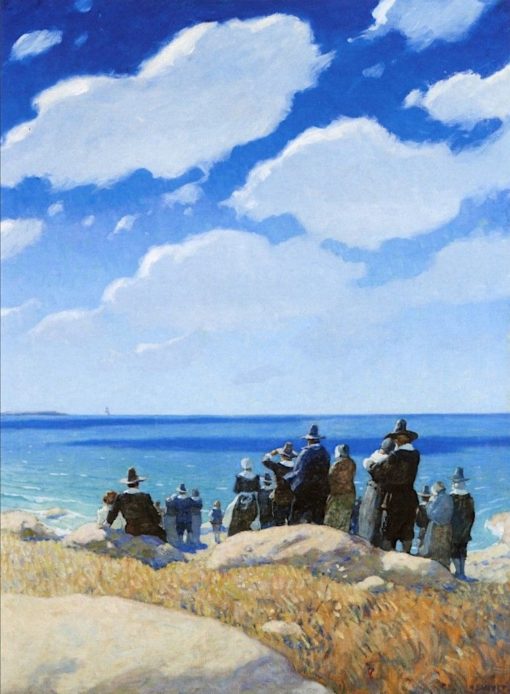

The Departure of the Mayflower, 1621, N.C. Wyeth, 1945

Four hundred years ago, on September 6, 1620, the Mayflower finally set sail from the southern coast of England for the New World. After half its passengers had emigrated to Holland for several years in their quest to worship God and Jesus Christ in peace, and after a series of recent delays, they were months behind schedule in its 3,000-mile trek across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Mayflower was known as a “sweet ship” because of the scent left behind from its usual cargo, wine. But after more than two months at sea with all but the crew crowded between decks, sandwiched between the top deck and the cargo hold, the merchant vessel had turned decidedly sour. It was 100 feet long above deck but even shorter where the 102 passengers resided, if you can call it that. One of them died at sea, as did a sailor, but there was (unbelievably) a baby born too. The hulking boat reeked and leaked; the passengers were soaked, shivering, and sick. The temperature had now dipped below freezing.

They were almost evenly split into two groups. The first conceived and organized the whole affair, the Puritan sect known as Pilgrims or “Separatists.” They’d separated themselves from the church of England and were fleeing religious persecution in the realm of King James. The Netherlands had initially been an improvement, but the Englishmen decided they did not want their children to become Dutch. The second group was made up of “Strangers,” as the Pilgrims called them, or unbelievers who were accompanying the “Saints.” They represented the company financing the venture and supplied practical assistance in the work of building a community from scratch.

While they were not the first English settlers—that was a decade before in Virginia—they together became the first permanent settlement in the Northeast British colonies of North America, which were known even then as New England. The region eventually grew into the power center of the vast untamed country.

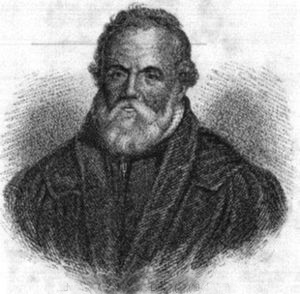

Among the Strangers was a young man in his early twenties named Edward Doty (R), born circa 1599. Thanks to a cousin who researched our family tree and submitted a DNA sample, I learned a couple of years ago that I was among Doty’s nearly hundred thousand descendants. I was born 360 or so years after him, part of the twelfth generation. Great-Grandfather Doty, I now call him for short.

Among the Strangers was a young man in his early twenties named Edward Doty (R), born circa 1599. Thanks to a cousin who researched our family tree and submitted a DNA sample, I learned a couple of years ago that I was among Doty’s nearly hundred thousand descendants. I was born 360 or so years after him, part of the twelfth generation. Great-Grandfather Doty, I now call him for short.

For me, at least, it has put a new zest or twist in the whole familiar story, or what used to be familiar.

All Americans used to grow up knowing the outline of the Mayflower saga—the harrowing sea voyage, the landing at Plymouth Rock, the brutal New England winter during which half of the settlers died, and especially the first Thanksgiving held by the Pilgrims with their neighbors, the Indians. Of course this is all now verboten. An even more mythic account dominates: The Native Americans were simply one big happy racial family, smoking peace pipes in a powwow together or outside their wigwams sitting cross-legged around a campfire eating and occasionally heading out to the fields to tend the crops or to hunt; the various tribes in the region (which were actually almost continuously at each others’ throats to conquer and rule over the other) all harmoniously coexisted. The English, as the new narrative goes, were imperialists, oppressors. The colonists were the true “savages.”

The real story, however, as so often is the case, is considerably less black and white than the revisionists pretend.

But the woke witch hunt rages on. The iconic Plymouth Rock, which the colonists may or may not have actually set foot on when they disembarked for the last time on their historic voyage, was defaced this year (in a year in which all-out war was declared on history). But whoever the culprits were, I think that at least we can be reasonably sure they weren’t professional vandals. Unlike the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which was unleashed last year to mark the 400th anniversary of the first slaves who arrived in America (in Virginia), which the journalists tried to claim is the true birth and sole legacy of the U.S. But some leading historians are fighting back; they in turn declared the series of articles, essays, videos and podcasts to be overwhelmingly misleading—they’ve even called for the Pulitzer Prize of its principal author to be revoked. What’s more, one of the Times’ own columnists admits in a lengthy essay that the project ultimately “has failed.” It appears that the Old Gray Lady, like many these days, is not only vengeful but very confused.

Exploring history can be disillusioning, even painful, whether national or personal. Along with Great-Grandfather Doty, for instance, my cousin’s genealogical excavations also revealed that I have a half sibling I didn’t know about. But individual lives and history in general are made up of many scenes, which need to be viewed in the round and in the context of the whole story to be properly understood.

The Pilgrims, in fact, planted the spiritual and civil seed that grew into a great nation like no other before it or since. So its roots were not only Christian in spirit, but all citizens, whether Saint or Stranger, believer or unbeliever, were equal under the law. It was all contained in a document of only a couple of hundred words that concisely and presciently set out the very course by which the colony and the new country would grow and flourish.

On November 11, 1620, two days after sighting land, the Mayflower finally anchored at Provincetown at the curled fingertip of Cape Cod. The ship first had headed for the mouth of the Hudson River, which was then part of the Virginia colony and the site for which the Pilgrims’ land patent had been granted, but had to turn back because of shoals and tempestuous waters between Cape Cod and Nantucket Island. Before the passengers even left the ship, the Pilgrims insisted that every man in the colony (excluding the ship’s crew) sign a pact. The Saints and Strangers had different allegiances, and the Pilgrims knew that anarchy would quickly lead to annihilation.

This was of course the Mayflower Compact, that trinity of seminal U.S. documents along with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our king and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do, by these present, solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony unto which we promise all due submission and obedience.

Forty-one men signed it. One of them was Edward Doty.

Great-Grandfather Doty was an indentured servant to the family of Stephen Hopkins, who was making his second trip to the New World. Hopkins had not only lived in Jamestown, Virginia, for two years, but on the way back to England was shipwrecked on Bermuda—an incident that’s said to have inspired Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

While Hopkins was no Prospero, just a merchant adventurer presumably looking for money as well as action or a new life, Great-Grandfather Doty, from what is recorded about him, seemed much more of a Caliban.

This is not to diminish what must have been his great guts and grit to even survive such exacting circumstances, much less thrive, as he seems to have done later. Some of the details we know about him are telling. Some, at least to me, are especially so.

First, he did not actually sign his name on the compact, but made his “mark”—he was illiterate. But we should not infer that he was totally ignorant, especially in practical matters; just because a person can’t read and write doesn’t mean he can’t think or learn or, what’s more, take action. As Shakespeare tells us, action is eloquence.

Interestingly, some of Great-Grandfather Doty’s descendants were extremely literate—even eloquent. Mercy Otis Warren, for instance, became a pamphleteer and one of America’s first female playwrights and historians of the American Revolution (Thomas Jefferson eagerly awaited the three-volume work and ordered subscriptions to it for himself and his cabinet). Charles Warren, her great-great-grandson, was a noted legal historian who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1922 for The Supreme Court in United States History.

The next mention of Great-Grandfather Doty was that he took part in an expeditionary force of sixteen men led by Miles Standish, the indomitable military leader of the colony, to find a suitable site for a permanent settlement. This was the third and longest such search since the Mayflower had arrived in the new Promised Land a month before.

Things had been pretty bad so far for the colonists. But they were about to get worse.

William Bradford, who served as governor of Plymouth Colony for three decades, gives a thumbnail portrait in Of Plymouth Plantation of what they were now up against. As the scouting party set sail on December 6 in a shallop from Provincetown into Cape Cod Bay, the spray from the roiling waves froze on their coats “as if they were glazed.” Over the next seven days, during which they made their way around the harbor to Plymouth directly opposite from the Mayflower, they were also attacked by Indians.

After finally building a settlement of seven dwellings and a “common house,” there was still little food. More and more in the colony grew ill. By spring only 50 of the 102 passengers were still alive. The Pokanokets, whose chief Massasoit was embroiled in a struggle for supremacy with the other local Indians, including the Massachusetts, offered to help; they showed them how to grow the local corn, maize, which was unfamiliar to the Englishmen, and beans and squash (the “Three Sisters” of Native American agriculture). Eventually the colonists signed a treaty with the tribe, which temporarily eased their minds.

But that didn’t stop attacks from within their own ranks.

Bradford records that in June, Great-Grandfather Doty and the Hopkins’s other servant, a young man named Edward Leister, injured each other in a duel. Neither was seriously wounded, except perhaps for their pride. The young firebrands were sentenced to have their feet and heads tied together. (An interesting tableau, to be sure.) But it was only for a short time; due to their pleas they were unbound.

Then there are the courts. Records show that Great-Grandfather Doty was involved in a number of legal cases over the remaining three and a half decades of his life. The charges included assault, theft, fraud, trespassing, debt, slander. Some of them involved men whose last names were Clarke—his in-laws, in other words. He was never severely punished and was fined only small amounts, which he duly paid.

Perhaps this is why, unlike all the rest of the original founders of Plymouth, Great-Grandfather Doty never held public office or even served on a jury. But it didn’t stop him from owning his share of real estate; he was apparently relatively wealthy.

But even if all of these shady dealings were his fault, Great-Grandfather Doty was eclipsed in that respect by one of his remote great-grandsons. Silas Doty, born in 1800 in St. Albans, Vermont, was one of the most notorious outlaws of the nineteenth century and perhaps in American history. His crimes and adventures sound like something out of a picaresque novel.

In his autobiography, The Life of Sile Doty: The Most Noted Thief and Daring Burglar of His Time, which appeared after his death, Cousin Sile (R) says he started stealing as a child—from his siblings, his teacher, the blacksmith. As a teenager he joined a counterfeiting gang in northern New York state and in a few years was the head of it. He learned blacksmithing but only so he could make his own custom burglary tools. In his early twenties the law was on his heels, so he fled to England where he eventually ran a crime gang in London. Again he fled to avoid arrest—he walked all the way to Liverpool and sailed to New York City under an alias. Since he’d worn out his welcome back home, he moved to the Midwest and took up where he left off. When a farmhand confronted him about a heist, he beat the guy to death with a walking stick and dumped him in a swamp. He was eventually charged with murder and sentenced to life. But he escaped from prison and headed to Mexico; it was now 1848 and the Mexican-American War was in progress, but instead of joining the army in exchange for amnesty he pillaged and plundered in the wake of the battles. After the war he returned to the Midwest, convinced the locals he’d received amnesty, and began a cycle of thieving and imprisonment that was only stopped by his death in 1876.

In his autobiography, The Life of Sile Doty: The Most Noted Thief and Daring Burglar of His Time, which appeared after his death, Cousin Sile (R) says he started stealing as a child—from his siblings, his teacher, the blacksmith. As a teenager he joined a counterfeiting gang in northern New York state and in a few years was the head of it. He learned blacksmithing but only so he could make his own custom burglary tools. In his early twenties the law was on his heels, so he fled to England where he eventually ran a crime gang in London. Again he fled to avoid arrest—he walked all the way to Liverpool and sailed to New York City under an alias. Since he’d worn out his welcome back home, he moved to the Midwest and took up where he left off. When a farmhand confronted him about a heist, he beat the guy to death with a walking stick and dumped him in a swamp. He was eventually charged with murder and sentenced to life. But he escaped from prison and headed to Mexico; it was now 1848 and the Mexican-American War was in progress, but instead of joining the army in exchange for amnesty he pillaged and plundered in the wake of the battles. After the war he returned to the Midwest, convinced the locals he’d received amnesty, and began a cycle of thieving and imprisonment that was only stopped by his death in 1876.

If even half of this is true (he is, after all, a con man of the highest—or I should say lowest— order), Cousin Sile’s wallowing life of crime is the most consummate violation of the eighth commandment I’ve ever seen or heard.

Sile Doty lived about midway between me and Great-Grandfather Doty. Edward Doty of Plymouth, Massachusetts, died on August 23, 1655. He left behind his wife, Faith Clarke, whom he had married when he was in his mid-thirties and she was around sixteen, and nine children. The next-to-last of the brood, Joseph, was the line I came from. Eventually my paternal great-grandfather married Gertrude Doty, and their granddaughter Gertrude became my grandmother.

I’ve never even been to Cape Cod, though it is only a couple of hundred miles from where I have lived most of my life. But I think now I’ll pay it a visit (off season). The Pilgrim Edward Doty Society has even erected a monument in Plymouth devoted exclusively to him.

Though he was a unbeliever, I am not. The Pilgrims strongly believed, as do I, that it was only because of God’s providence that the colony endured that first year in the New England. By worldly standards, they should’ve perished. “But with God,” as Jesus says, “all things are possible.” And the Pilgrims certainly were with God—they left all they knew behind and risked their lives to worship him and his son freely and the way they believed was proper. So they held a feast with their Indian neighbors and friends, the Pokanokets, to celebrate and to thank God for the bounty and his grace.

So before my wife and I dig into the turkey and fixings at our Thanksgiving table this month, in my usual prayer thanking God for all the blessings he has given us this year, I’ll make sure to mention Great-Grandfather Doty and the Plymouth Colony that he and the others, despite their faults, sowed and nurtured. After all, without him there would be no me. And without him and the rest of the stalwart Mayflower survivors there would likely be no United States of America—at least not as we know it.

And that would be a great loss. For me personally, of course, but I think for the whole country and the whole world.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Jeff Plude, a former daily newspaper reporter and editor, is a freelance writer and editor. He lives near Albany, New York.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast